From the chronicles of the Rhine comes the story of Wotan and the cursed gold. A Gothic tale of madness, betrayal, and eternal lament, whispered in hushed tones by those who dared to remember. The moon hung low over the jagged peaks of the forested mountains, casting an eerie silver glow on the mist-shrouded Rhine. Deep within its inky waters lay the Rhinegold, a treasure of unimaginable power and malevolence. For centuries, it had remained hidden, guarded by the ethereal Rhine Maidens, whose haunting beauty was matched only by their mysterious nature. In a decrepit castle perched atop a cliff, Wotan, the Vampire Lord, brooded over his decaying domain. His once-glorious reign was threatened by the relentless spread of death and decay. Beside him, his wife Fricka, a vampiress of unrivaled beauty and cunning, whispered dark prophecies of doom. "We must act, Wotan," she urged, her eyes glowing with an unholy light. "The power of the Rhinegold can restore our dominion over the night." But to seize the Rhinegold, Wotan needed the cunning of Loge, a shape-shifting trickster, a fire starter, whose allegiance was as fluid as the mists of the river. Loge had whispered to Wotan of a vile creature, Alberich, who had stolen the Rhinegold and renounced love in order to forge a ring of immense power. In the depths of Nibelheim, Alberich, now a monstrous, rotting lich, commanded a legion of his fellow Nibelungen. The ring had twisted his soul, turning him into a necromancer of terrifying might. His army of the enslaved, animated by the dark magic of the ring, spread terror throughout the land. Wotan and Loge descended into the bowels of the earth, where the air was thick with the stench of death. They found Alberich in a cavern lit by the sickly glow of the cursed gold. His eyes, sunken and lifeless, gleamed with malice as he caressed the ring. With a serpentine grin, Loge whispered into Alberich's ear, promising him eternal dominion over the living and the dead if he joined forces with Wotan. Blinded by his lust for power, Alberich agreed, not knowing he was ensnared in a web of deceit. Back at the castle, Wotan, with the ring in his grasp, felt its dark power coursing through him. But as he donned the ring, a terrible curse was unleashed. The skies darkened, and the once-vibrant forests withered into a wasteland of twisted trees and skeletal remains. The ring's malevolent influence began to consume Wotan, turning him into a being of pure darkness. Fricka watched in horror as her husband transformed, his vampire essence corrupted by the ring's insidious magic. Desperate, she sought the counsel of Erda, the ancient earth goddess, who revealed the ring's ultimate doom. "Only by returning the Rhinegold to its rightful place can the curse be broken," she intoned, her voice echoing like the whispers of the dead. Before Wotan could respond, a terrifying crash echoed through the castle. The giant Fafner, a colossal undead beast with hollow, glowing eyes, had come to collect a debt. Years ago, Wotan had promised Fafner the lovely Freia, the goddess of youth and beauty, in exchange for building the fortress Valhalla. Now Fafner had come to claim his prize. With a roar that shook the very foundations of the castle, Fafner seized Freia in his massive, decaying hands. Her screams of terror echoed through the halls as Wotan and Fricka watched helplessly. The giant's strength was too great, even for Wotan in his corrupted state. "We must save her!" Fricka cried, her eyes blazing with desperation. "Without Freia's apples of youth, we are doomed to wither and die." Loge, ever the schemer, saw an opportunity. "We can trade the Rhinegold for Freia," he suggested. "Fafner's greed is boundless; he will accept the gold in her stead." But Wotan, now a shadowy wraith, refused to relinquish the Ring's Power. Consumed by madness, he unleashed his fury upon the world, commanding legions of the undead in a reign of terror. The Rhine Maidens, sensing the growing darkness, rose from the depths to reclaim the Rhinegold. Their voices, haunting and mournful, echoed through the desolate lands, calling forth the spirits of the fallen. In a climactic battle beneath the blood-red moon, the Maidens confronted Wotan, their ethereal forms shimmering with a ghostly light. But the battle turned against them. Wotan's newfound power proved too great, and one by one, the Maidens were driven back into the shadows. Loge, true to his duplicitous nature, betrayed them, ensuring Wotan's victory. As the final Maiden was cast down, the ring's malevolent power surged, binding the Rhinegold irreversibly to Wotan's dark soul. In the aftermath, the mournful lament of the Rhine Maidens echoed through the lifeless forests and desolate lands as the daughters of the Rhine, once epitomes of all good and grace, themselves turned into creatures of the night. The Rhine River, once a symbol of life and beauty, flowed black and corrupted, its waters a testament to the darkness that now reigned. Software: DALL-E & Adobe Photoshop

- Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

The music, too, was of ineffable inspiration. Insensible as I am to music in general, I cannot escape the magic of Wagner, whose genius caught the deepest spirit of those ancestral yellow-bearded gods of war & dominion before whom my own soul bows as before no others -- H.P. Lovecraft, the master of cosmic horror and the creator of an intricate mythos was known for his complex relationship with art and music. In his letters, Lovecraft often expressed a rather limited appreciation for music, noting that his enjoyment was largely through associative memory rather than intrinsic appreciation. Yet, amidst his general indifference, he showed, at least on one occasion (see quote above) his admiration for Richard Wagner. Lovecraft’s sporadic admiration for Wagner provides a fascinating insight into how the operatic grandeur and mythological depth of Wagner's works could resonate with Lovecraft's own literary cosmos. (Lovecraft is not known to have ever attended a Wagner opera in full production. Note that what follows is a toying with ideas, this article by no means tries to prove something.) LOVECRAFT’S MUSICAL INDIFFERENCE AND WAGNERIAN EXCEPTION Lovecraft's self-professed indifference to most music is well-documented. He confessed to deriving more emotional appeal from simple, patriotic tunes like It's a Long Way to Tipperary or Rule, Britannia than from the complex compositions of, let's say, Liszt, Beethoven and (also) Wagner. Lovecraft acknowledged his limitations in enjoying music but avoided the common pitfall of deriding what he did not comprehend. Instead, he expressed a form of reverence for those who could appreciate the musical intricacies. THE MYTHOLOGICAL DEPTH OF WAGNER AND LOVECRAFT One of the most compelling reasons Wagner's operas might resonate with Lovecraft lies in their shared affinity for mythological and ancestral themes. Wagner's operas, particularly his monumental cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, draw heavily on Germanic and Norse mythology. These narratives evoke a sense of ancient grandeur and cosmic struggle, elements that are central to Lovecraft's mythos. Lovecraft's writing often delves into the ancient and the cosmic, exploring themes of forbidden knowledge, ancient gods, and the insignificance of humanity in the face of the universe's vastness. The grandeur and complexity of Wagner’s mythological narratives could easily mirror the vast, eerie cosmos that Lovecraft constructed in his stories. Wagner’s ability to evoke a deep sense of the primeval and the sublime through music might have provided Lovecraft with a rare artistic resonance, bridging his literary worlds with the operatic grandeur of ancestral myths. THE EMOTIONAL AND AESTHETIC PARALLELS Emotionally, both Wagner and Lovecraft create works that transcend their mediums to evoke profound, often unsettling emotions. Wagner’s music is known for its ability to convey intense emotions, from (temporarily) triumph to the (inevitable) tragic downfall of heroes. Lovecraft, through his prose, elicits a different emotional response—fear, awe, and a sense of the unknown. The emotional depth in Wagner’s compositions might have spoken to Lovecraft’s appreciation for the dramatic and the otherworldly, offering him a glimpse into the emotional potential of art that he otherwise found elusive. Aesthetically, Wagner’s innovative use of leitmotifs—recurring musical themes associated with particular characters, places, or ideas—parallels Lovecraft’s own use of recurring motifs and themes throughout his works. Just as Wagner's leitmotifs build a complex, interwoven narrative structure, Lovecraft’s recurring references to his pantheon of eldritch beings and forbidden tomes create a rich, interconnected mythos. This structural similarity might have further enhanced Lovecraft's appreciation for Wagner, recognizing a kindred complexity in the narrative techniques they employed. OPERA & CTHULHU To the Wagnerian universe, we add a monster. Because good stories, even those already rich in drama and conflict, can always use a monster (see the movie Godzilla Minus One). So what if Cthulhu, Lovecraft's most famous creation, pops up in a few of Wagner's operas? DIE WALKÜRE From the inky depths, a monstrous shadow began to emerge. The sea swelled and churned violently, as if recoiling from the dark presence rising from its heart. Tentacles, each the size of ancient oaks, broke the surface, writhing and twisting as they reached for the sky. The water around them frothed and bubbled, releasing a noxious mist that spread across the coastline. The Valkyries gasped in unison, their courage momentarily shaken by the sight before them. SIEGFRIED Wotan meets Cthulhu: Wotan, in his guise as the Wanderer, enters the scene. He is on a quest to observe the unfolding fate of his grandson, Siegfried, who is destined to forge a new future. As Wotan approaches the place where he wants to summon Erda, the goddess of the Earth, the atmosphere grows oppressive. The air itself seems to thrum with a dark energy. Wotan: What dark power stirs in this ancient wood? A force beyond the ken of gods and men. My spear, once mighty, quivers in my grasp, As shadows deepen and the light grows dim. (The mist thickens, and from the depths of the forest, Cthulhu’s massive form begins to emerge. The creature’s sheer size and otherworldly nature defy comprehension.) Cthulhu (communicating telepathically, his voice a deep, resonant echo that reverberates in Wotan's mind): Wotan, king of gods, your time has come, The age of man and gods alike shall end. I rise from depths where madness dwells, To claim this world as mine, beyond your ken. Wotan (struggling to maintain his composure, confronts the cosmic horror before him): Great Old One, from realms unknown, you tread, But this is not your time, nor your domain. The Norns have woven fate’s unyielding thread, And Siegfried’s hand shall forge a new refrain. (Cthulhu’s presence warps the very fabric of reality around him, the forest seeming to bend and twist.) Cthulhu (with an aura of ancient, incomprehensible power): The fate you speak of matters not to me, For I am eternal, beyond time’s frail chains. Your world shall crumble, your Valhalla fall, As chaos reigns and madness stains. Wotan (steeling himself and raises his spear): Then let us clash, titans of different spheres, For the sake of man and gods, I’ll stand my ground. Though doom may follow, and Valhalla fade, In this twilight hour, our fates are bound. TANNHÄUSER The Pilgrims’ Chorus As the pilgrims sing, their hopeful hymn is interrupted by an unnatural silence. The air grows thick with an oppressive force. Emerging from the lake, Cthulhu's form casts a shadow over the procession. The pilgrims’ song becomes frantic, their hymns morphing into desperate pleas for salvation. The lush, redemptive melody of their song twists into something darker, reflecting the terror of encountering a being beyond mortal comprehension. TRISTAN UND ISOLDE Emerging from the darkness, towering over the trees, was a grotesque, monstrous figure. Its eyes, glowing with an otherworldly light, fixed on Isolde. As she faced the eldritch horror, Cthulhu’s deep, resonant voice filled her mind. "The monster is within," it seemed to say, "for your deepest fears and desires have summoned me." In that moment, Isolde realized that their forbidden love, their yearning to escape the confines of their mortal lives, had conjured this manifestation of their innermost darkness. The monster was not merely an external force but a reflection of her own tortured soul, an embodiment of the fears and desires that drove her into his arms. AND IN CONCLUSION ...

Software: DALL-E, Adobe Photoshop & After Effects

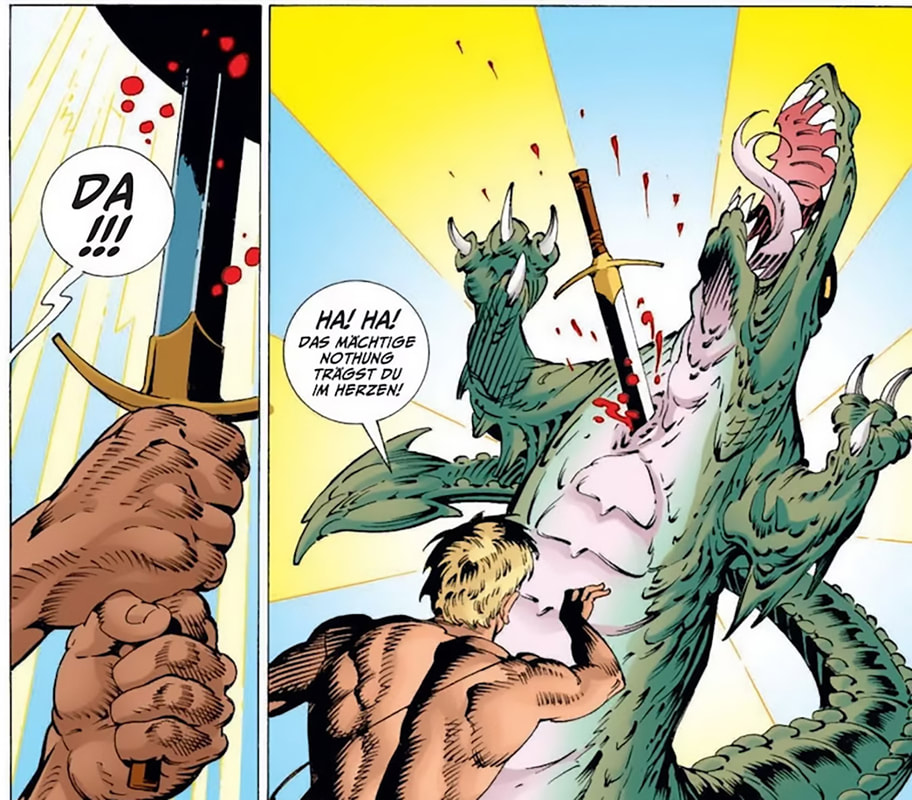

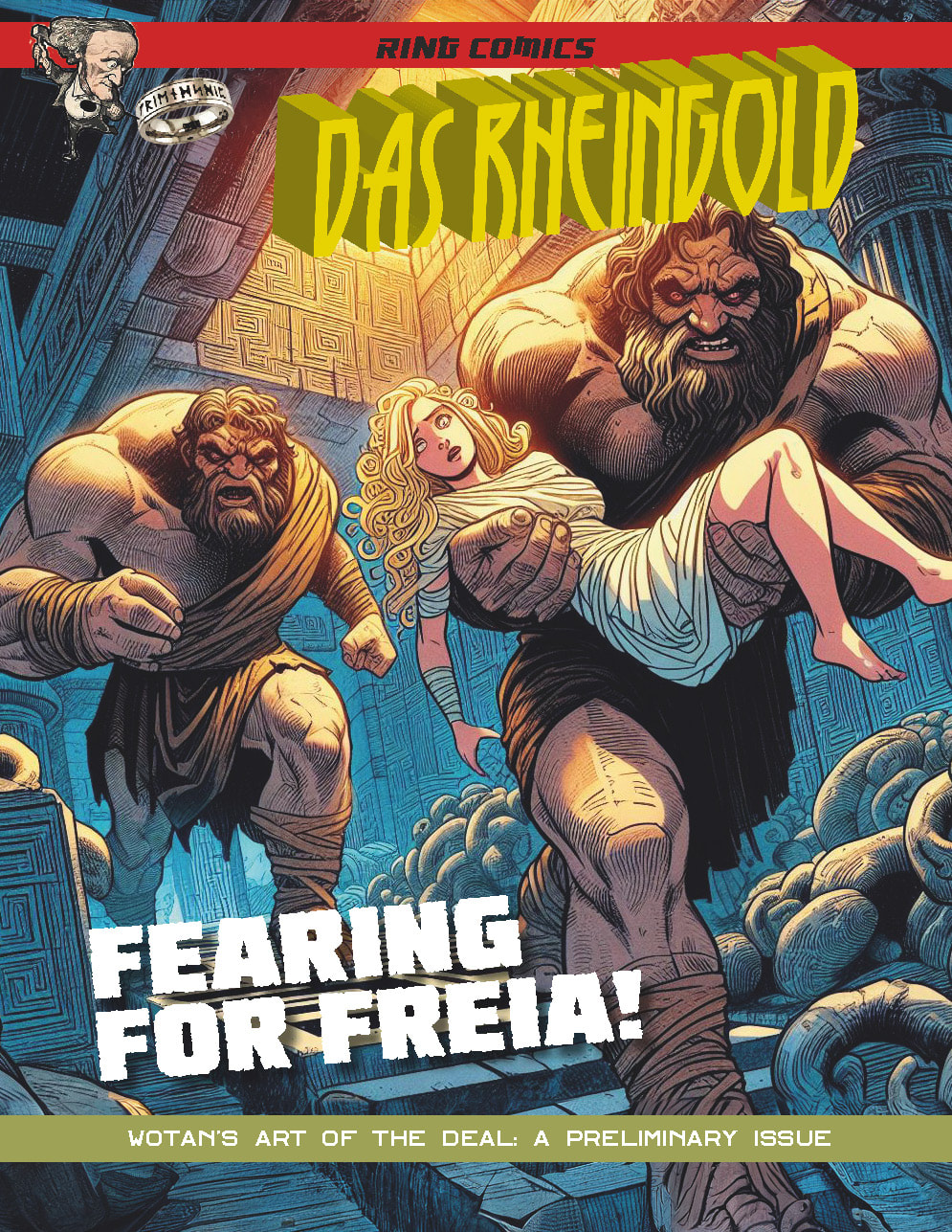

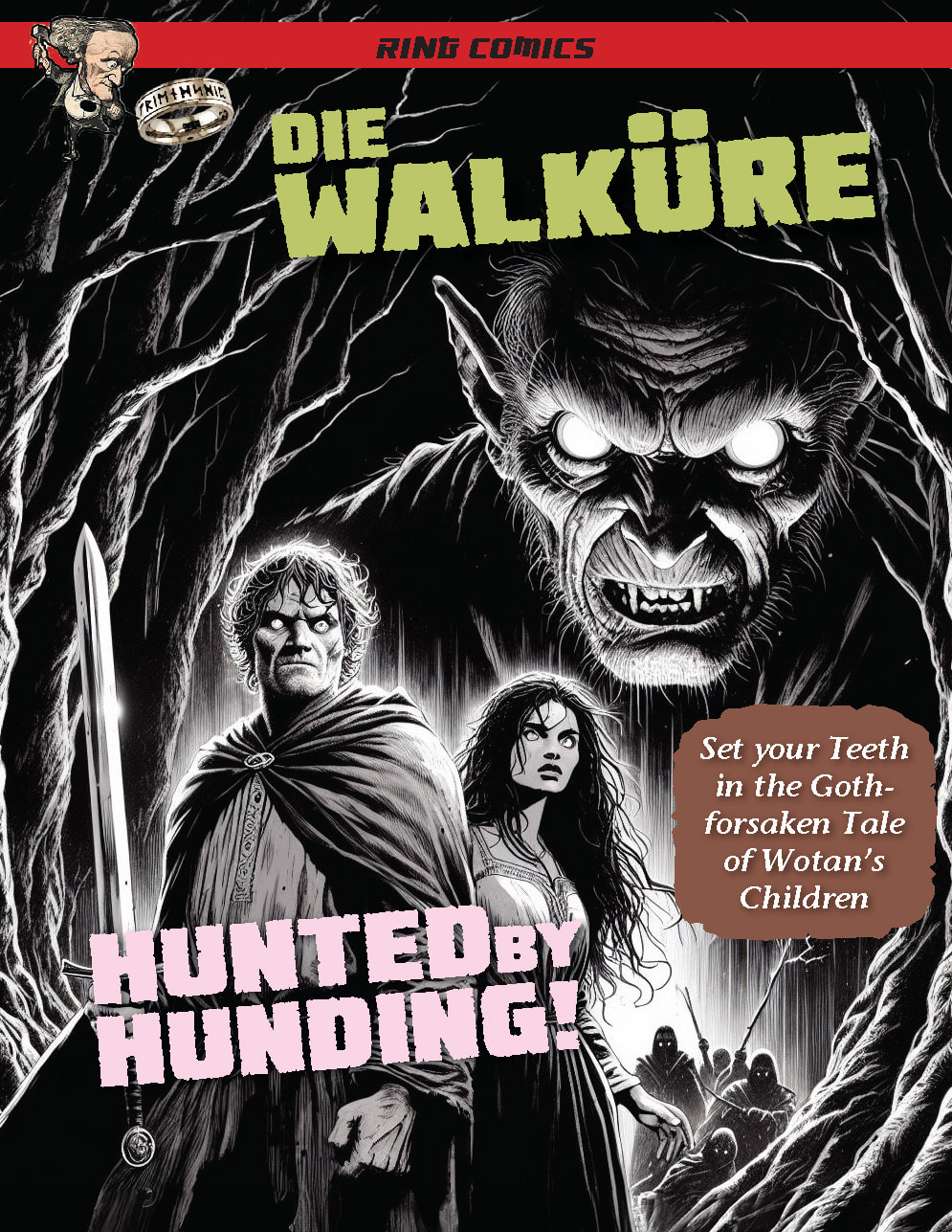

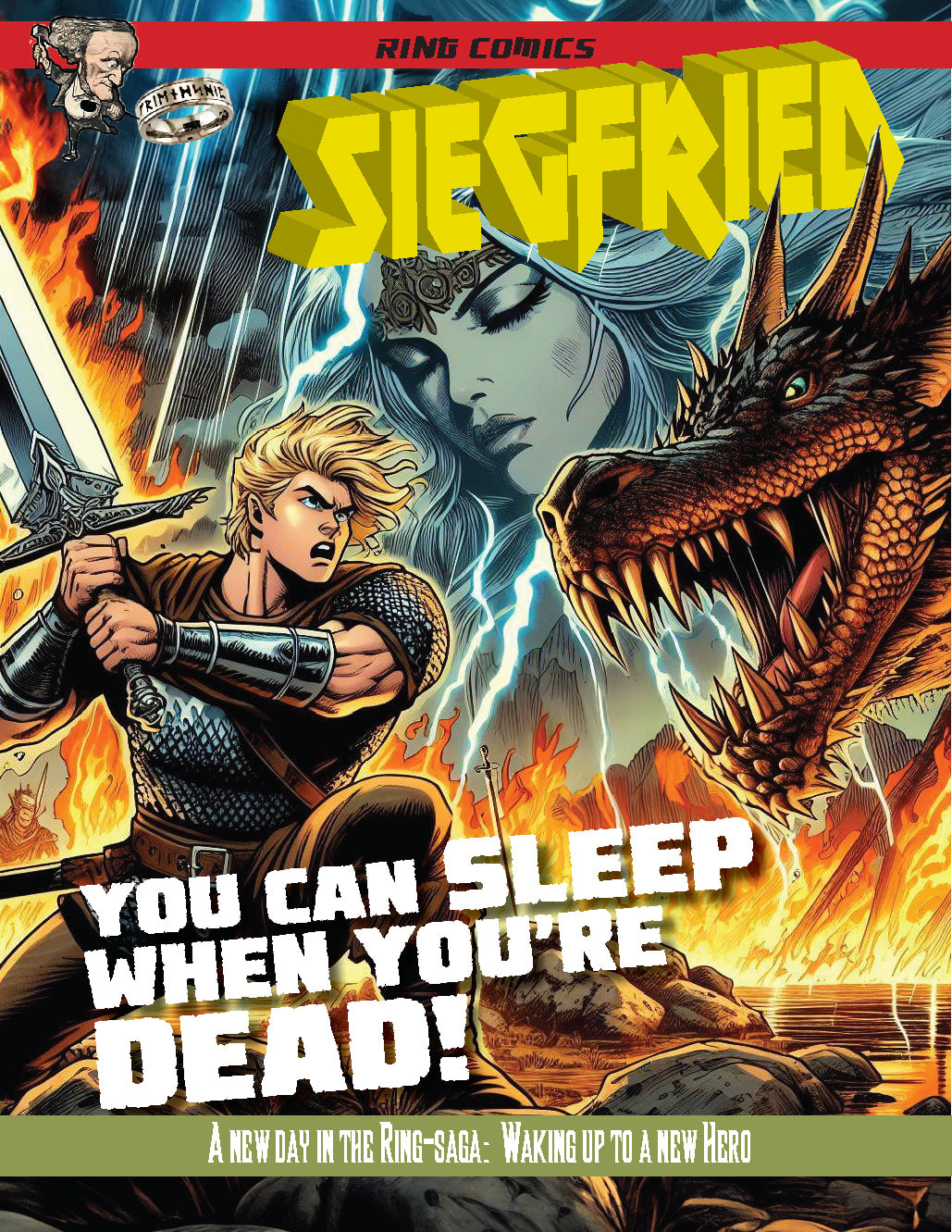

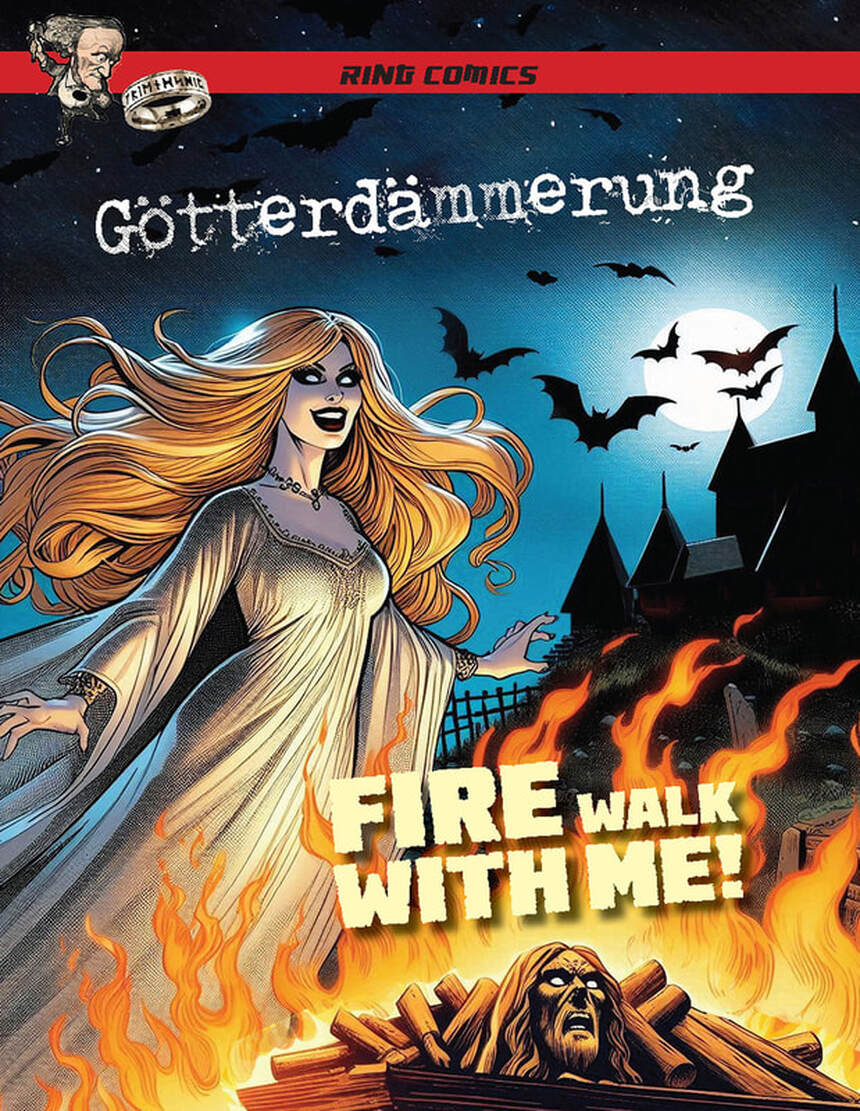

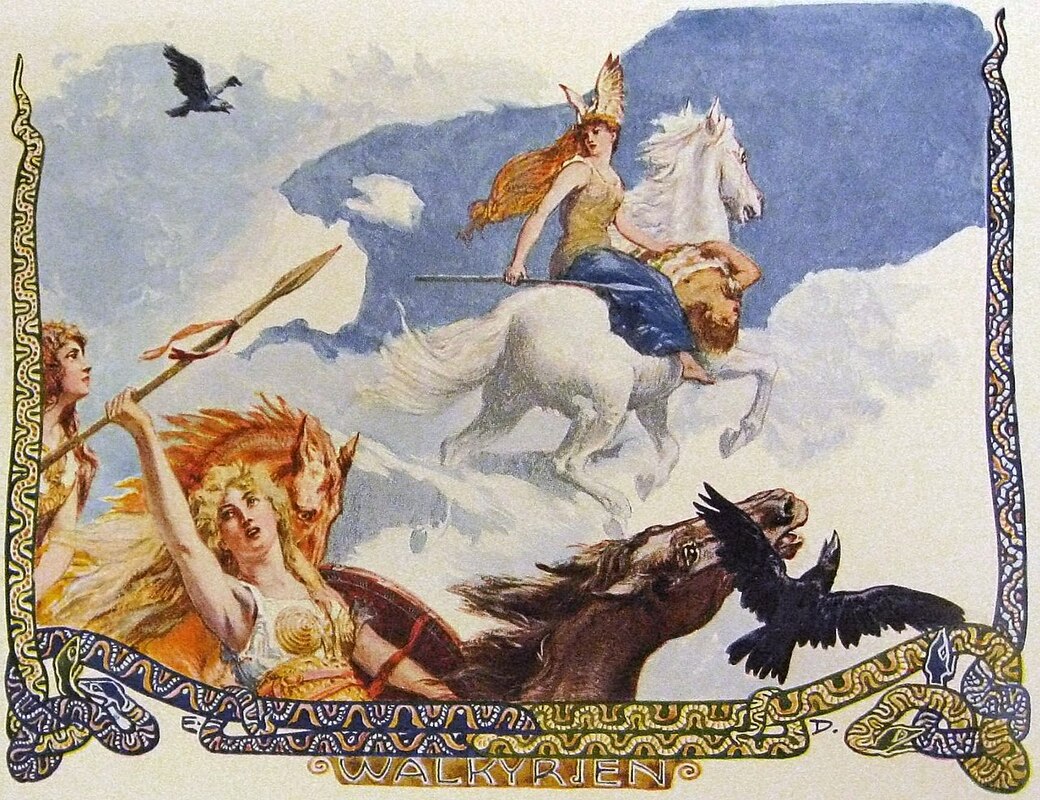

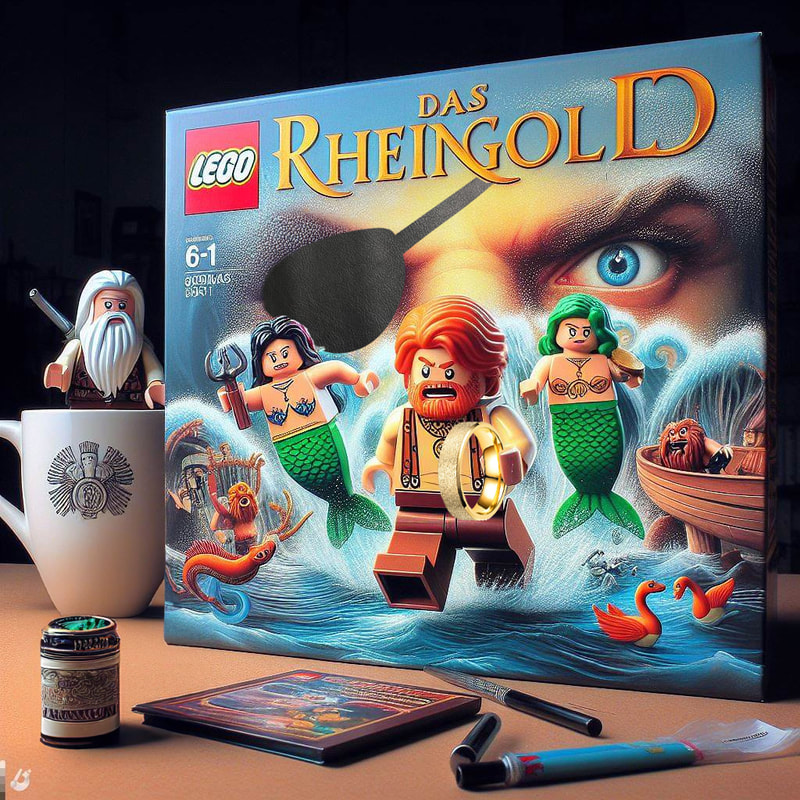

- Wouter de Moor About Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen in graphic novels. About graphic novels of the Ring that exist and those that don't (and can only be judged by their cover). This blog post includes images created using AI. Right from the premiere of the complete cycle in 1876 at the Bayreuther Festspielhaus, the operas of Der Ring des Nibelungen have inspired artists. The highly imaginative musical dramas (and their highly imaginative composer) were the inspiration for paintings, drawings and, later, comic books. We have, of course, the comic books (or graphic novels) of the complete Ring by P. Craig Russell on the one hand, and the series by Roy Thomas and Gil Kane on the other (before he could incorporate the Ring into a graphic novel, Roy Thomas was already warming up by incorporating the story of the Ring into a Thor-storyline for Marvel Comics: New Asgards for Old).

JUDGING A BOOK BY ITS COVER Especially fun for people who do know the Ring operas, I think, are the following covers of a comic book series that doesn't exist. It's a bit like making movie posters for films that were never made. A poster that evokes a film that exists only in your mind and, perhaps for that reason, fascinates all the more. As an extension of those film posters, which announce something that will never be seen, this is a series of comic books that tell the story of Richard Wagner's Ring des Nibelungen. Books that can only be judged by their covers. All images of the following covers are made with the help of an AI-image generator. Taking a moment of Das Rheingold, the adbuction of Freia by the giants, mentioned by Fricka, not seen on stage, and highlighting it in comic book fashion. So that the graphic depiction of that moment can take on a life of its own, beyond the original story. I have always found the combination of Wagner and the gothic element very attractive. Der fliegende Holländer is, of course, the most obvious opera to make that association but Die Walküre also lends itself perfectly to a gothic atmosphere. What if Hunding were a vampire? Siegfried is essentially an opera about characters trying to sleep ((this goes for both Fafner and Brünnhilde). Until they are awakened by the hero of the Ring, that is. The cover image for the third part of the Ring is in straightforward, action-packed (super)hero-style. Although ravens are definitely horror-worthy, it's not Wotan's ravens but a sky full of bats on this cover for Götterdämmerung where the final part of Wagner's tetralogy gets a push towards a Hammer-movie. With Brünnhilde as a witch-like ghostly apparition. EPILOGUE Of all the artists who ventured into Wagner's Ring, Arthur Rackham's drawings from the beginning of the 20th century are perhaps the most famous. Anticipating the graphic novel and largely determining the image we now have of the world of Der Ring des Nibelungen. A fantasy world that we now regard as a more or less natural representation of what the Ring world should look like. Russell's and Thomas's graphic novels are heavily indebted to Rackham's art. But in search for a staging on paper there is, of course, no harm in thinking beyond that kind of 'natural' visualisation. To ponder about visual material in ways as it already happens in theatres (I hear you shout, "Oh no, spare me the Regietheater!"). To illustrate a core and essence of the Ring-story in ways only a comic book can. (I am thinking of an artist like Dave McKean, artist of the outstanding Batman / Arkham Asylum). The design of that ultimately lies within the realm of creative freedom and an audience willing to open up to an artist's vision. The latter will not be a problem because Wagner's Ring continues to fascinate, not only musically but also theatrically and visually. Software: DALL-E, Adobe Photoshop & Illustrator

- Wouter de Moor Die Walküre, the next chapter in the 'authentic' Ring conducted by Kent Nagano is a marvel of narrative musical splendour. And although the 'nineteenth-century' sound here provides less of a surprise than with predecessor Das Rheingold, this is a breathtaking journey through the first day of the Ring. In the year 2021, we were offered an encounter with a Wagner opera in a performance based on historical research. The result of this historically-informed performance of Das Rheingold exceeded all expectations and dispelled the possible reservations one could initially have about such an undertaking with the strongest possible resolve. Instead of being exposed to stiff museum atmospheres, we were taken into a maelstrom of haunting excitement. The nineteenth-century instruments and their replicas blew a breath of fresh air through Wagner's work, making the performance effortlessly rival the Wagner summit. And now, three years later, Kent Nagano and Concerto Köln, joined by musicians from Dresdner Festspielorchester, return with the next chapter of the Ring. It must be said that the surprise and delight that the historical approach to Das Rheingold gave us was somewhat less imposing with Die Walküre. Once again, we were confronted with Wagner's nineteenth-century instrumentation containing the organic, pleasantly unsteady sounds of the brass and woodwinds. The overture, Winter Storm, sounded through the gut strings, crystal clear and heady. It was the beginning of a Walküre that rushed rapidly towards Wotan's farewell. The acts lasted 60, 80 and 65 minutes respectively, making this Walküre one whose second act, at 80 minutes, would fit on one CD; a rarity as far as I know. This speed did not come at the expense of the dramatic moments; they were given enough weight, it did sound swift, not rushed. That there was less of a revelation here could partly have to do with the context in which the performance of Das Rheingold took place at the time - for the first time since the Covid pandemic, we were able to attend a fully cast Wagner opera again. In view of its reception as part of a full Ring, something else might be added. As 'just' a preliminary evening, Das Rheingold, in full production and in concert performance, often comes with a promise that is not quite fulfilled in the remainder of the cycle. This is especially true for staged productions (I'm thinking here of the last Ring in Bayreuth, where it becomes weaker by each part, but also of Frank Castorf's Ring there, although Castorf recovers after a weak Walküre in Siegfried) but here, of course, that promise lay in the sound of a historically informed performance. How that sound would make us listen to Wagner differently. It was as if that historically informed performance elevated Das Rheingold more to a performance in the outclass than Die Walküre. As if Das Rheingold held more musical interpretative potential because it was less 'finished' as an opera than its successor. The historically informed performance revealed many previously unheard nuances that elicited unprecedented theatrical expression from the first part of the Ring. The sound of the orchestra was like an X-ray vision of Wagner's instrumentation, and in the historically informed treatment of the voices, Das Rheingold seemed at times to anticipate someone like Kurt Weill. Proto-cabaret in a musical drama where the treatment of the text serves expression, and everything, including its beauty (Wagner loved Italian bel canto), was set to that purpose. Indeed, with the musical storyteller Wagner, music is not mere music, but a means of conveying a story (one wonders to what extent he would have been successful in writing symphonies, compositions where you cannot lean on a story). As a prelude, it is great (my appreciation for it has only grown in recent years), but the drama in Das Rheingold does not yet reach the heights of its successor Die Walküre. Die Walküre is three dramas for the price of one, and Wagner unleashes them on the listener with a Schubertian sense of melody. Each act is a drama that can stand on its own. Going home after the first act, we would have experienced a story with a hopeful ending. In the second act, that hope is brutally dashed and we witness the death of a hero, Siegmund. The third act begins with one of the most recognisable tunes in music history, the Walkürenritt, a musical boost after the dystopian conclusion of the previous act. With Wotan's farewell that third act ends with one of the most beautiful pieces in the entire opera catalogue. In Die Walküre, the imaginative world Wagner creates is painted with nineteenth-century instrumentation in transparent tones and refined brushstrokes. The bombast with which Wagner is often associated was absent here. Even in the Walkürenritt, the windows remained wide open and the sound remained clear at all times. At times it was akin to a radio play, with even the singers with relatively modest voices not having to force themselves anywhere. With everything neatly proportioned, both orchestra and voices, in the acoustics of the Concertgebouw, not exactly an easy task, the narrative power took precedence over the orchestral power. The love between Siegmund and Sieglinde is doomed. That love is doomed because of the laws Wotan has imposed to subjugate the rest of the world. (And of course Wagner knows that stories that end badly make more of an impression than a happy ending.) The fact that Wotan also binds himself in the process is something he is pointed out insistently by his wife Fricka. She makes it clear to Wotan that he must remove his hands from the incestuous love of the Wälsungen twins if he is not to undermine his own power, and the power of the gods. The laws of marital union that condemn the love between Siegmund and Sieglinde are emphatically not dictated by nature. They are artificial, imposed by a supreme god, and are all too human in character. Morality is a social concept and it seems that here, it is impossible not to sympathise with the Wälsungen pair, Wagner deliberately presents incestuous love as an act of resistance to the bourgeois mores that dictate how people should relate to each other. Wagner himself would have plenty more to cope with this when he begins a relationship with the married Cosima von Bülow-Liszt and when his affair with Mathilde Wesendonck forces him to take refuge in Venice. (The composer incorporates his own worldly struggles into his work, and the tantalising way in which he does so tends to make people, then and now, forgive him for his less-than-pretty traits and behaviour. As Hans von Bülow said after Wagner ran off with Cosima: "If it had been anyone but Wagner, I would have shot him.") In Die Walküre, Wagner encounters the primacy of music in his search for his desired musical drama. In the music of magic fire (in the third act), he unlocks a symphonic potential that he will fully explore in Siegfried. In the historically informed performance, that symphonic potential is given less space (less voluptuous weight) to manifest itself; it has to make room for an almost chamber-musical approach. With radio play-like moments as a result. With Wotan's great monologue in the second act, thoughts turned to what Wilhelm Fürtwangler once called his favourite performance of an opera. That was a performance of Die Meistersinger in Bayreuth in 1912, conducted by Hans Richter, during which he was barely aware of the music. It was an ideal symbiosis of all the components of a total theatre. The music here too, with a smaller orchestral sound, more than in an orchestra with modern instruments, is at the service of the singers. The transparency in the orchestral image reveals details that add a subtle nuance to the listening experience. It certainly contributes to a better understanding of the musical architecture and the newly perceived details can enrich the story in new ways. That the music is entirely at the service of the singers was entirely according to Wagner's intentions but a transparent orchestral sound was not. In his own Festspielhaus, Wagner placed the orchestra below the stage because the singers' intelligibility was an absolute priority. This resulted in an orchestral sound in which the various instrumental parts melted together more and sounded less clear overall. After the premiere of the Ring in 1876 at the Bayreuther Festspielhaus, Wagner therefore thought of rearranging the orchestral parts. But perhaps even more than by the historically informed orchestral sound, the difference from other modern performances was determined by the singers' treatment of the text. That treatment of the text was more linked to the immediacy of the spoken word. For the singers, the first stage for rehearsing their texts consisted of pronouncing them where they found their tempo and intonation. Only then did the singing follow. The result was a singing that was less pompous and which, even in the more exuberant moments, was more in the service of narration than vocal prowess. This allowed, for instance, Siegmund to be cast with a smaller voice than is usually the case. Ric Furman's tenor flourished best in the more lyrical moments, though a bit more mass would have been welcome in the big dramatic moments. The same could be said of Christiane Libor's Brünnhilde. Patrick Zielke's Hunding was like a piece of basalt in this cast of relatively small voices. A bit angular but that suited exactly the brute who slaves Sieglinde to be his wife. Not small in voice was likewise Derek Walton's Wotan. His vocal impact was imposing, although he could have used a bit more lyricism to make the Werdegang of the supreme god more dramatically palpable. An observation that, in the light of the performance, was little more than a side note. After Wotan's farewell, I was floored. Empty and purified. Tired yet fulfilled. As if I had experienced something of magnificent importance. Exactly as it should be after a Wagner opera. Die Walküre, Concertgebouw Amsterdam, 16 March 2024 Kent Nagano conductor Concerto Köln Dresdner Festspielorchester Derek Welton bass-baritone (Wotan) Ric Furman tenor (Siegmund) Sarah Wegener soprano (Sieglinde) Patrick Zielke bass (Hunding) Claude Eichenberger mezzo-soprano (Fricka) Christiane Libor soprano (Brünnhilde) Natalie Karl soprano (Helmwige) Chelsea Zurflüh soprano (Gerhilde) Ida Aldrian mezzo-soprano (Siegrune) Marie-Luise Dreßen mezzo-soprano (Roßweiße) Eva Vogel mezzo-soprano (Grimgerde) Karola Sophia Schmid soprano (Ortlinde) Ulrike Malotta mezzo-soprano (Waltraute) Jasmin Etminan alto (Schwertleite) - Wouter de Moor

2024:

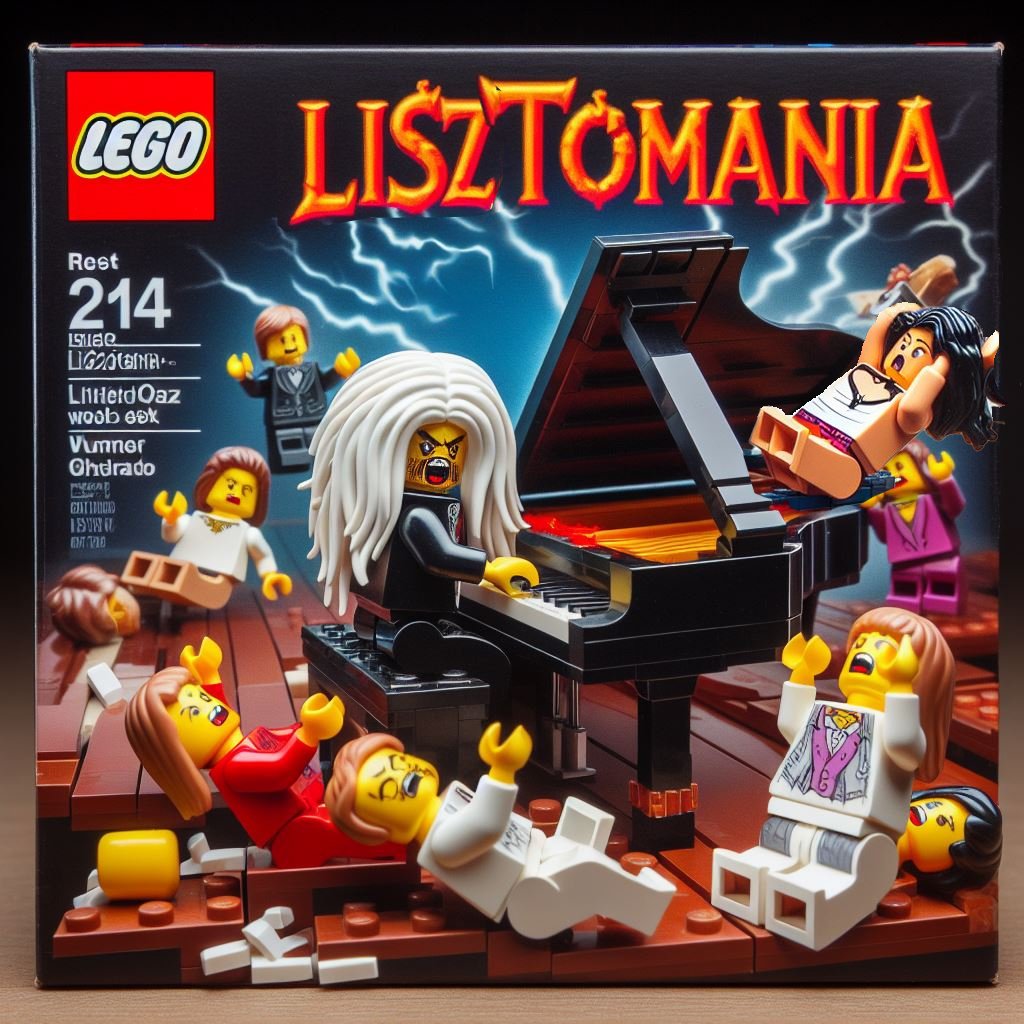

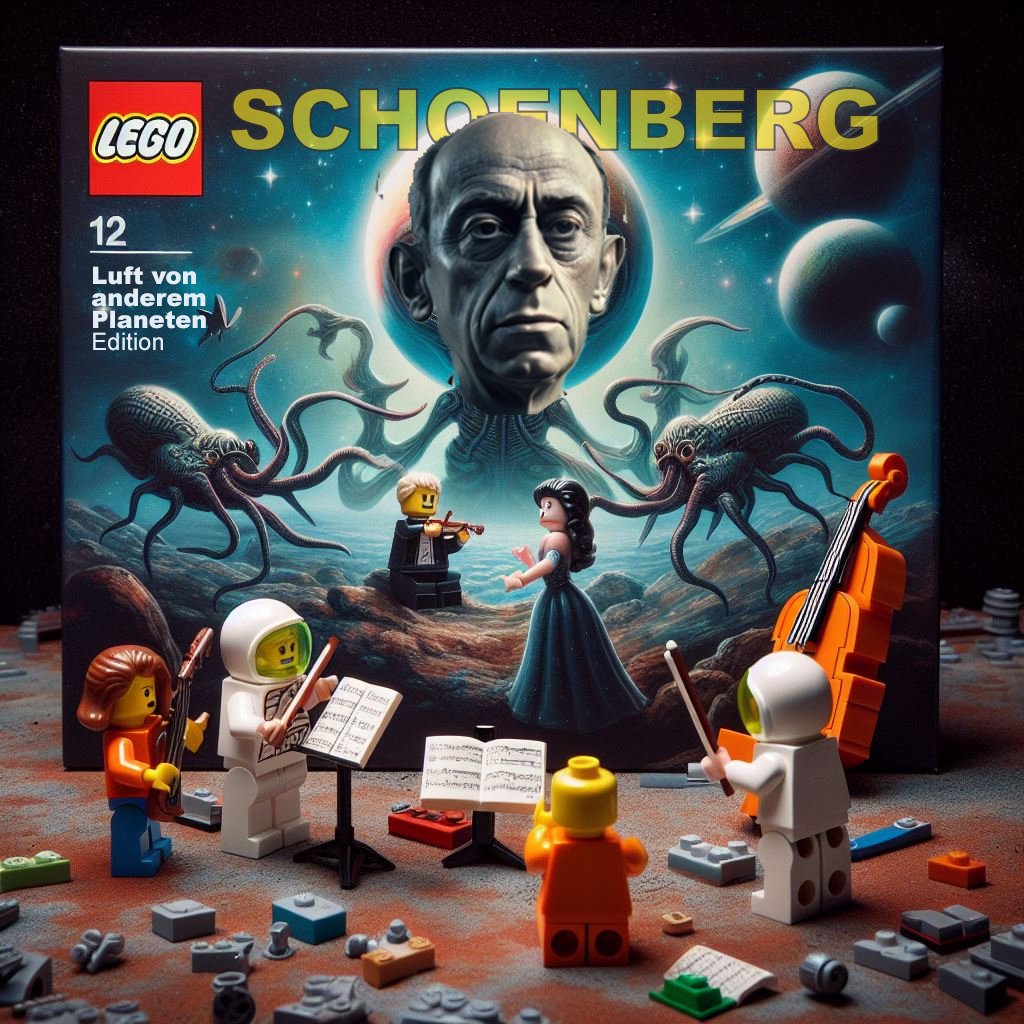

THE RHINE GOTHIC WAGNER & H.P. LOVECRAFT WAGNER & COMIC BOOKS DIE WALKURE (HIP) 2023: GOING TO LEGOLAND LIVING COLOUR SIEGFRIED IN A GLORIOUS WALL OF SOUND LOHENGRIN IN THE FACTORY CASSANDRA: VOICES UNHEARD THE MERCILESS TITO OF MILOU RAU AUFSTIEG UND FALL DER STADT MAHAGONY BAYREUTH (TANNHAUSER AND PARSIFAL) THE STEAMPUNK RING THE DAY OF THE DEATH MAHLER AND THE RESURRECTION TIME (DER ROSENKAVALIER & METALLICA) 2022: KONIGSKINDER (A TRIUMPH IN TRISTESSE) DER FREISCHUTZ DAS RHEINGOLD (HIP) UPLOAD (LIVING IN A DATA STREAM) 2021: DER SILBERSEE A (POST?) COVID PARSIFAL THE WRITE OF SPRING 2020: A DESCENT INTO THE NIBELHEIM OF THE MIND EDDIE VAN HALEN WAGNER AT THE MOVIES WITH MAHLER AND STRAVINSKY INTO THE NEW YEAR 2019: THE RETURN OF DIE WALKÜRE PAGLIACCI / CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA: A GAME WITH REALITY IN ITALIAN VERISMO (NO) BAYREUTH (SUMMER BLOG) TANNHAUSER: WHAT'S ON A MAN'S MIND ABOUT EXTREME MUSIC DIE TOTE STADT HELMUT LACHENMANN IN THE MOZART SANDWICH 2018: OEDIPE: IS MAN STRONGER THAN FATE? ONE MORE ... (RING CYCLE) MARNIE: OPERA & PICTURES THE HALLOWEEN TOP 10 JENUFA: ICE-COLD REALITY IN WARM-BLOODED MUSIC MY PARSIFAL CONDUCTOR: A WAGNERIAN COMEDY LOHENGRIN: IN THE EMPIRE OF THE SWAN DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE IN A ROLLER COASTER PARSIFAL IN BAYREUTH HEAVY SUMMER (THE ROAD TO PARSIFAL) LOHENGRIN IN SCREENSHOTS LESSONS IN LOVE AND VIOLENCE BERLIN/BLOG: FAUST & THE CLAWS OF TIME THE GAMBLER: RUSSIAN ROULETTE WITH PROKOFIEV BACH/BLOG#1: THE ROAD TO LEIPZIG BACH/BLOG#2: BACHFEST LEIPZIG BACH/BLOG#3: JOHANNES PASSION & MORE DER FLIEGENDE HOLLÄNDER, WAGNER & DRACULA THE CHRISTINA CYCLUS OF KLAS TORSTENSSON LA CLEMENZA DI TITO: MOZART ÜBER ALLES BRUCKNER AND THE ORGAN GURRE-LIEDER: THE SECOND COMING PARSIFAL IN FLANDERS: REIGN IN BLOOD TRISTAN & ISOLDE AND THE IMPOSSIBLE EMBRACE DANIELE GATTI & BRUCKNER'S NINTH 2017: ON THE BIRTHDAY OF LUDWIG (BEETHOVEN'S MIGHTY NINE) THE DINNER PARTY FROM HELL ZEMLINSKY & PUCCINI: A FLORENTINE DIPTYCH VENI, VIDI, VICI ELIOGABALO (HERE COMES THE SUN KING) LA FORZA DEL DESTINO DAS WUNDER DER HELIANE 'EIN WUNDER' TO LOOK FORWARD TO EIN HOLLÄNDER IN BAYREUTH FRANZ LISZT IN BAYREUTH SALOME & THE WALKING DEAD LOHENGRIN IN HOLLAND 2016: WAGNER WEEKEND THE SUMMER OF 2016 PARSIFAL IN SCREENSHOTS (BAYREUTH 2016) BEING TCHAIKOVSKY GUSTAVO & GUSTAV: DUDAMEL & MAHLER HAITINK & BRUCKNER: A NEVER-ENDING STORY DAVID BOWIE FOR LEMMY AND BOULEZ BOULEZ IST TOT 2015: LEMMY - ROCK IN PEACE THE BATTLE: WHO'S THE BETTER LOHENGRIN? STOCKHAUSEN AND HEAVY METAL FRANZ LISZT IN THE FUNNY PAPERS TRISTAN UND ISOLDE DER ROSENKAVALIER SOLTI'S RING AND BAYREUTH IN 1976 EASTER CHANT BOULEZ TURNS 90 HOLY TINNITUS FRANZ LISZT IN THE PHOT-O-MATIC THE HOLY GRAIL FRANZ LISZT - ROCK STAR AVANT LA LETTRE 2014: THE BEST THEATER EXPERIENCE IN MY LIFE Music evokes images. A record comes with a cover. To listen to an opera is to look with your ears. Music can unlock a world in the mind waiting to be made visible. And an AI-image generator can be a handy tool for that. After previously toying around with prompt design, resulting in the image gallery of Der Ring des Nibelungen in Steampunk-style, Wagner & Heavy Metal goes to Legoland. Music from my adult life staged with the toys of my early childhood. It's a versatile toy, you can make all sorts of things with it, which perhaps because of its limitation is still so popular. It's like building something in low resolution with 3D pixels where the Lego bricks, even if they only exist virtually, add a decidedly tactile dimension (indispensable in a digital world). We begin with history's first rock star, Franz Liszt, the man who reinvented the piano, a bit like Jimi Hendrix reinvented the electric guitar. A man whose concerts delighted his audiences (women!) in proto-rock-like fashion. Next: the man whom Liszt saw as the starting point for the musical innovation of the 19th century; Ludwig van Beethoven. “Beethoven’s music sets in motion the machinery of awe, of fear, of terror, of pain, and awakens that infinite yearning which is the essence of romanticism.” — E. T. A. Hoffmann Richard Wagner, as well as being a composer, was a man of the theater. When asked what images to add to that illustrative music of Wagner, Frank Castorf came up with fascinating and frustrating answers for his Ring production for Bayreuth. The result, however, stuck. Since that Ring production, the crocodile has been a visual leitmotif that automatically brings thoughts to Siegfried. Nor has the image of Wotan eating spaghetti left me since. Bayreuth is host to some of the most daring Wagner productions in the world, and Tobias Kratzer's Tannhäuser and Stefan Herheim's Parsifal are certainly amongst the most bold and successful. Productions in which the mind-boggling sound world of Wagner finds a worthy partner in the imagination of the theatermaker. Hans Neuenfels' Lohengrin production introduced me to the hallowed ground of the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth and to the often avant-garde productions of Wagner's operas that this festival stages. There I learned to appreciate the kind of stagings that take a free interpretation of the source material, even if those interpretations seems counter-intuitive. Better a production that dares to make choices than one that playes it safe. After all, for the ideal staging you always can, and especially in a Wagner opera, rely on your own mind. When I attended Lohengrin at the Festspielhaus in 2014, I felt those jitters again that I knew from my youth, those jitters when I first attended a concert of my idols Rush. I consider their album 2112 my introduction to heavy metal. There was little more heavy in those years than the title track and the priests of Syrinx. Slayer has always held a special place in heavy metal. With Slayer, no danger of metal sounding stiff. Their music, with its abrupt tempo changes and out-of-the-box (atonal!) guitar solos, creates a realm of sound that combines tightness and looseness in a way that is unique in metal - metal mayhem in which time flies by so fast it seems to stand still. It makes Slayer (with Jeff Hanneman and Dave Lombardo!) at their best moments sound more like an extension of an electric jazz band on steroids than a hard rock band. Slayer proves that in order to take your breath away, music (any music) has to breathe. With their third studio album, Reign in Blood, the band reached the top of the trash metal Mount Everest. Back to operaland where things can also get very bloody. An opera like a slasher-movie is Richard Strauss' opera Elektra from 1909. A screaming-for-vengeance opera that brought domestic relations to dystopian lows and drama in the genre of opera to new musical heights. Alban Berg's Wozzeck was the first opera I saw live. Reducing Wozzeck to atmospheric music to a tragic story does Alban Berg's musical drama a disservice (Karl Böhm called Berg a greater dramatist than Wagner) but the cinematic component in Berg's music is unmistakable. It made the first atonal opera in music history arrive at me a lot more accessible than expected. Moreover, it made me curious for more. Fortunately, there was also Lulu (Berg's other, second, opera and this guilty pleasure). After Alban Berg, it was tracing the path back to the founder of the Second Viennese School. The air of other planets in Arnold Schoenberg's second string quartet with soprano was a path to a new music and a breath of fresh air. At the end of many an opera, many a main character dies. For Tristan and Isolde, that death is a portal to a world where they can finally be together. A world beyond the perception of the senses. An opera that is like a fever dream in which you can die of undying love. In Wagner's highly visceral music lurks a staging. It is perhaps for this reason that a Wagner opera often presents itself in an ideal way in a concert performance. In Siegfried, Wagner gives free rein to the symphonist in him. Here he seems to have less consideration for the singers' audibility. In Bayreuth, that audibility is guaranteed because the orchestra is below the stage. In a concert performance, however, the singers must contend with an orchestra at full exposure. In that glorious wall of sound, coming form the ideal sound system that is the Wagnerian orchestra, a world reveals itself into which you, as a listener, love to get lost. The more you try to make something look realistic, the more you see that it is fake. To be appealing and believable, a certain degree of abstraction is indispensable. Wagner was notoriously unhappy with the 'natural' staging of the first Ring production in Bayreuth in 1876 (the only production he saw in his life, except in Bayreuth also in Berlin at Angelo Neumann's Ring-on-tour). He let it be known after that premiere that next time it would all have to be different. How it should be done then was an answer that remained unanswered at the time of his death. We now know that definitive answers to the staging questions posed by the Ring do not exist, nor is it desirable to look for them. We conclude with a more or less 'traditional' design of the Ring operas, after all that Regietheater, with ample room for the fantasy element. Software: Microsoft Bing, Adobe Photoshop

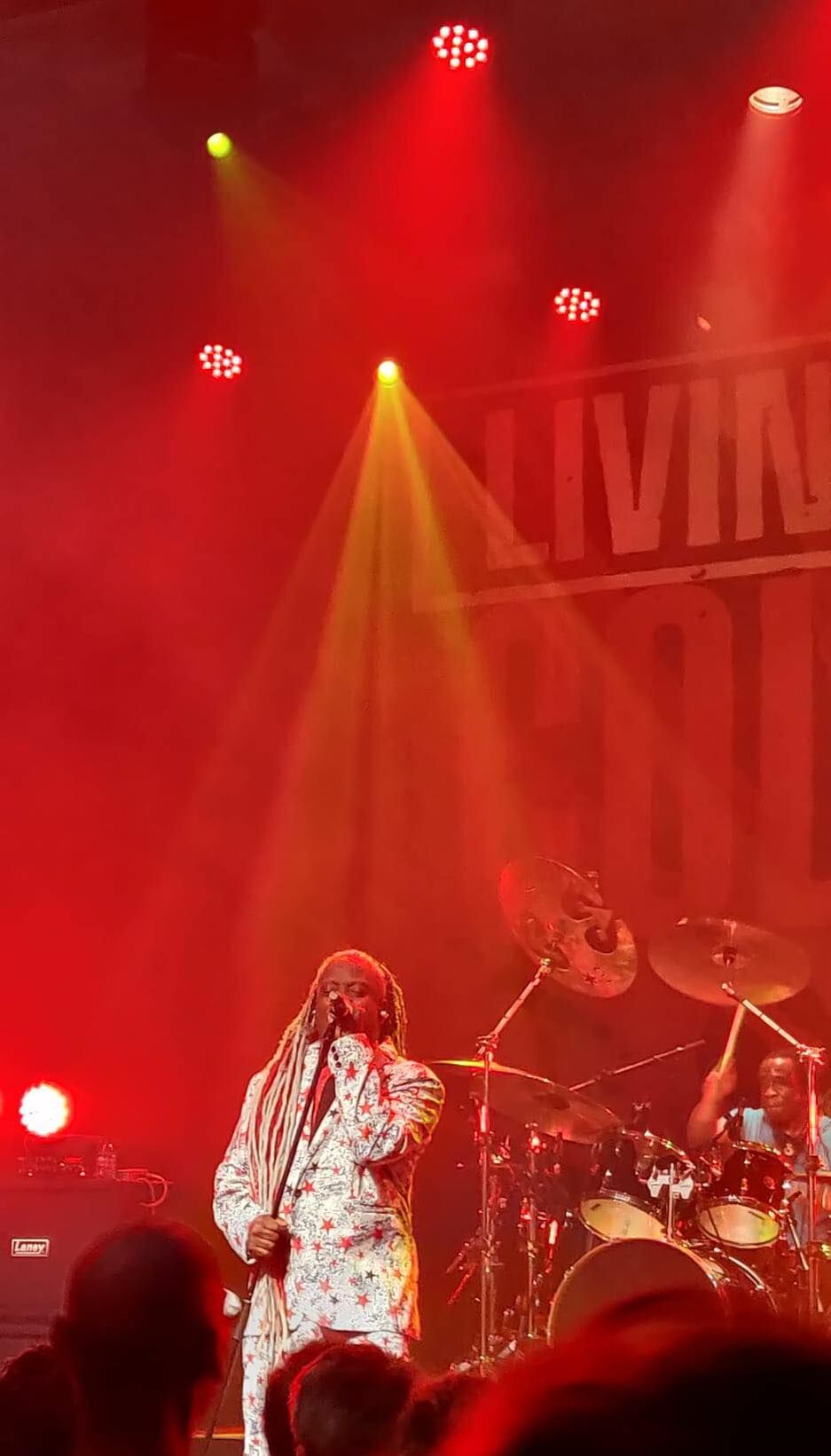

- Wouter de Moor Time's never up for the hard-edged and multicoloured metal of LIVING COLOUR. After more than three decades in the business the New York-quartet still enchants the senses with craftsmanship & passion. The 1980s were drawing to a close. The decade in which bands like Rush and Metallica did deliver their best work, but also the decade in which pop music largely lost me as a listener. The sound of the 1980s was the sound of music in a blister pack. Music whose kitsch stuck so nasty to the eardrums that the sound of names like Spandau Ballet and Cock Robin make the hairs stand up straight in the back of my neck to this day. It would not be until 1991 that Nirvana, with Smells Like Teen Spirit, would give the final blow to the plastic pop sound of the previous decade (and for that alone, Kurt Cobain deserves a statue). A few years earlier, in 1988, Living Colour had shed light in those sonically dark times of celestial mediocrity with their debut Vivid. The record was a storm of fresh air that blew open the door of the (then) white bastion of rock music. A record that would make mixing genres hip and was part of a movement that I will conveniently call funk rock. I started fishing in a pool in which bands like Fishbone, 24-7 Spyz, Red Hot Chili Peppers and Faith No More were swimming. Living Colour made music that confirmed what you actually already knew, that genre boundaries don't really matter that much. Living Colour not only rocked hard, they also, as is often the case with good music, made you curious about where their music came from. Through Living Colour, I followed the path back to bands like Bad Brains and Funkadelic. Bands that were like the missing link between Jimi Hendrix and the hard rock of that era I was listening to. Living Colour complemented your knowledge and expanded the mind. I kind of lost track of them after their third record Stain. A gig, as part of the European leg of the Stain 30th Anniversary tour, was a re-encounter with the heroes of my youth. It was an utter pleasant and insistent reminder of what a beast of an album Stain was, and what a powerhouse of a band Living Colour still is. It lasted two songs. It took band and sound a bit to find each other, but once the quartet embarked on an integral performance of their album Stain, it was all hit and no miss. Go away, opening track from that record, with a riff from the meat grinder, set the tone for a party in multicoloured sound. Forged with metal that splits skulls -spiced with punk, funk, soul, hip-hop, trip-hop and jazz- they enchanted the senses with passion, craftsmanship and elegance. Living Colour was never a band that resorted to mere platitudes and simple tricks to make their music accessible and engaging. Instrumentation and vocals do not follow each other in obvious ways. No melody over a chord progression played with just barre chords. Beneath those ever-lyrical vocal lines lies a volcano of harmonically and rhythmically challenging instrumentation that sizzles and boils. The exceptional musicianship of the quartet from New York has always guaranteed dazzling live performances but at this gig the band sounded exceptionally inspired. "Never take a sold-out venue for granted," Vernon Reid had tweeted prior, and that thought and feeling translated into a performance that did what good live performances do. It purified and it liberated body and mind. That the music has more than just stood the test of time was no surprise - we took note of it with exhilaration and delight. Frantically singing along to songs until your head is loose on your neck is sometimes what a person needs on a Friday night at the end of the week. That that person, in politically shaky times, feels a song like Ignorance is Bliss closing in on him and notes that the band's lyrics are as relevant today as they were three decades ago was an experience that was not undividedly liberating. Times don't necessarily change for the better and, like three decades ago, Time's Up. Still. The riffs coming from the guitar of Vernon Reid were like insights cleaving the mind, with his solos exploring the territory from James Blood Ulmer back to John Coltrane - tapestries of notes manifesting into sheets of sound. Sound eruptions that created a sense of freedom, an energy of anything goes, something one finds, for example, in artists as diverse as Prince in his best guitar solo moments, as well as Slayer's Kerry King. The undulations in Corey Clover's voice were by turns like a caress of the evening wind and a scream from the underworld. Doug Wimbish took a moment to celebrate the anniversary of half a century of hip-hop. Wimbish was on fire. This time no fiddling with a laptop, thankfully, but full focus on inspired bass playing that, in a choreography of flowing movements and driving power, smashed its low notes like graceful splotches of paint on a colourful canvas.

LIVING COLOUR, Gebouw-T, Bergen op Zoom, 8 December 2023 - Wouter de Moor

A concert performance of Siegfried where the orchestra presents itself as the ideal medium to experience Wagner. Because with Wagner, as nothing else in the world of opera, the music is the staging. At the end of Die Walküre, Wagner lights a fire with orchestral means. A fire that is both earthly and magical. It is a fire in which you see the flames twirl. It is a fire in which you hear a world come to life. Listening to Wagner is like watching with your ears. And this moment - the moment when the magic fire, lit by Loge, invoked by Wotan, with which Brünnhilde is safely shielded from anyone who is not the greatest of all heroes - is the moment in the Ring when the ambitions of the orchestra exceed those of the singers. From here you could say that the symphonist Wagner abandons his original goal, the Gesamtkunstwerk, because he discovers a new force of expression in music that only confirms the primacy of music over everything else. In Siegfried, Wagner gives full rein to his symphonic ambitions. He seems to have less regard for the singers' audibility; the instruments seem at times to deliberately overpower the voices. In Siegfried, opera in which the hero of the cycle makes his entrance, he builds a wall of sound with which he draws the listener into a world that overwhelms and seduces. That listener cannot help but follow the master, into the forest where the hero will slay the dragon, and to the rock where Brünnhilde awaits her valiant knight. Looking with your ears gets an extra boost in a concert performance (hifi on steroids!). A performance in which orchestral splendor together with singers that are acting, with a single prop (Siegfried's horn), and a Waldvogel singing from the balcony are more than enough to bring Wagner's Ring world to life in a uniquely evocative way. The mind goes where the ears lead it and the eyes need little to no inducement to follow the music to a world outside place and time where gods, giants and dwarfs are busy surviving and working themselves up in the food chain. The ring that falls to Siegfried after he kills the dragon curses anyone who carries it. Yet Siegfried takes it, after the Waldvogel points it out to him. Nature has been corrupted from the beginning, from the moment Wotan cuts off a branch of the world ash to make a spear in which he carves the runes to subjugate the rest of world. The Waldvogel seems to be proof of that corruption. Her moral compass seems broken when she tells Siegfried to pick up the ring. Unlike in the Nibelungen saga on which he is based, where his character is shaped mainly by his actions, Siegfried's personality in Wagner's opera is for an important part shaped by the young man's search for himself and his origins, his mother. In the forest through which he wanders, he is looking among flora and fauna for something, someone, that can put him in touch with himself and his identity. Wagner excels in introspection and recapitulation. His music dramas are narratives of the mind. Not to speak short of the physical action (Fafner beating Fasolt to death, Siegmund's death, Siegfried killing the dragon), it plays a relatively minor role in the Ring. The real action is in the characters' state of mind. To shape their roles, the singers need little more than expression and gestures. It is perhaps for this reason that a Wagner opera shows itself in an ideal mode of presentation in a concert performance. The performance of Siegfried by the Radio Filharmonisch Orkest conducted by Karina Canellakis showed the third opera of the Ring as a robust soundscape, a kind of mega-symphony with voices. It was a long-held wish of Canelakis to perform Siegfried in its totality. Her conducting was solid, not excessively exuberant, which perhaps could not be otherwise with two weeks of rehearsal time where one week with the singers. Siegfried, the opera, showed itself here in an impressive wall of sound. A symphonic fairytale forest painted in frenzied wild colours. Unlike staged performances where the orchestra is in the pit, the singers had to compete against an orchestra at full exposure. They showed, even in those parts where they seemed to be at the losing end in the decibel battle with the instrumentation, boldness and class. Of the singers, Ya-Chung Huang's Mime and Clay Hilley's Siegfried were well matched in voice and expression. Hilley was still struggling a bit with a few high notes at 11am, but his stamina and delivery in the heaviest tenor role in operaland were impressive. Once he arrived at the final duet, a sonic eruption of passion and borderline lunacy, he found, in Daniela Köhler's Brünnhilde, a woman who teaches him what fear is and someone who united her passion and primal drift in a remarkably compelling way. Her Brünnhilde retained, in the face of the orchestra which here, in the final stage of the opera, was fully propelled by Canellakis, complete control over her voice.Nowhere did she force, always her voice remained defined and in possession of maximum expression. Amongst a cast of standouts, Köhler was the standout. It was a performance where the orchestra presented itself as the ideal medium to experience Wagner. Because with Wagner, as nothing else in the world of opera, the music is the staging. Siegfried, Concertgebouw Amsterdam, 25 November 2023 Radio Filharmonisch Orkest Karina Canellakis conductor Clay Hilley tenor (Siegfried) Ya-Chung Huang tenor (Mime) Iain Paterson bas-baritone (Wanderer) Markus Brück baritone (Alberich) Tobias Kehrer bas (Fafner) Daniela Köhler soprano (Brünnhilde) Judit Kutasi mezzo soprano (Erda) Gloria Rehm soprano (Waldvogel) - Wouter de Moor

The Dutch National Opera's new production places Lohengrin in a barren factory hall. A place where amid the bleakness of everyday life the promise of a miracle is cultivated. A place that hosts a performance in which singers, orchestra and conductor excel.

With Lohengrin, Wagner took a formidable musical step toward his dreamed Gesamtkunstwerk, a work of art in which all disciplines, text, music and theater are a proportionate part of the end result. That Gesamtkunstwerk would not ultimately come about in its initially conceived form. The primacy of music was simply too great for that. The sound world of Lohengrin is a breathtakingly euphonic landscape in which you are entrained for nearly four hours and in which you are only too happy to get lost. Listen to Lohengrin, with the (Italian) number opera in mind, and you become aware of the giant step Wagner takes here toward an operatic form that seamlessly integrates the various components of the music (chorus, recitative and aria) into a musical drama that flows and does not stagnate. The choral scenes and individual arias here are not so much climaxes, not points of arrival, but constantly new points of departure. The result is a breathtakingly euphonic soundscape in which you are entrained for almost four hours and in which you are only too happy to get lost. The prelude, a music that is like a flower that slowly opens and unveils a world in which the promise of something beautiful in tantalizing sounds preludes to its fulfillment, is the starting point of a story in which light breaks through in the bleakness of everyday life. The colorful, hallucinatory sound world of Lohengrin is given an industrial gray cast in the new production of the Dutch National Opera. The factory hall in which the story unfolds is the epitome of a bleak reality in which people have nothing to expect - the hall can be seen as a reference to the time in which Wagner composed the opera, a time of advancing and increasing industrialization. In that world, the hatches literally open when a miracle presents itself. When Lohengrin arrives, the back wall of the hall lifts and light enters. The knight Elsa has dreamed of turns out to really exist. With the arrival of the swan knight, the people may hope for something magical in a disenchanted world and the king may hope for a welcome military reinforcement for his army. The hope pinned on the arrival of a strong man has unmistakably religious, Messianic traits (the fascination Wagner had with the character of Jesus of Nazareth, as in his last opera, Parsifal, does not go unnoticed). Next to that is the arrival of a strong man in a German opera historically brisant (the opera was a favorite of Adolf H. The "Sieg! Heil!" from the libretto, after Lohengrin defeats Telramund, still feels uncomfortable). Director Christof Loy leaves the historical connotations of the play for what they are and concentrates on what he believes to be the core of Lohengrin's drama. For him, that core lies largely in the loss of trust. Elsa does not trust Lohengrin, cannot accept him for what he is: an unknown savior in distress who must remain unknown if he is to continue to exist among men. The forbidden question, hanging over the opera in word and musical motif (Nie sollst du mich befragen), is one that is inevitable from a human point of view. As a human being, you have a right and reason to know with who you ultimately are dealing with. But it harbors here an extremely bleak picture of human relationships. Trust erodes irrevocably (despite, or perhaps mainly because of, prior agreements and commitments). Wagner's most lyrical opera, then, is perhaps the one in which he is most somber about the relationship between man and woman, the connection between two individuals. It postulates the idea that it cannot ultimately endure, not because of external influences, but because of intrinsic factors. As a director, Loy enjoys working intensively with singers about the motivations of the characters they portray. That dedication manifests itself in the detail of the Personenregie. When he is embraced as a savior, you can see the doubt and regret on Lohengrin's face. As if he knows what will happen in the end. As if he is in a movie he has seen before. It is a crucial element in the direction of persons in which details are at the heart of a production in which major choices in stage setting are absent. The dynamics on the static stage are provided by the ballet that Loy, as in his earlier productions for Tannhäuser and Königskinder, brings in to physically express a generally prevailing feeling or to emphasize the mood surrounding an (imminent) event. For example, the ballet frames the arrival and announced departure of the swan knight with beautiful choreographed wings. Like a kind of Greek choir in motion that comments on the action without actively interfering itself with that action. It breaks the uniformity and somberness on stage. The king hardly stands out in his outfit compared to his herald. The people in the factory hall walk around in an equally colorless and unremarkable manner. The same goes for Lohengrin, who, despite his stylish entrance, walks around in rather anonymous clothing without any reference to the fairy tale world he comes from. The visual part of the production may remain on the flat side in Loy's direction and Philipp Fürhofer's design, but the musical performance more than does justice to the fascinating arena of extremes that make Wagner's world of Lohengrin (and his other operas) so irresistible. Until now, Lorenzo Viotti was known as an opera conductor primarily for Italian repertoire, and it will probably not be for nothing that his first adventures in Wagner led him to Lohengrin. The opera in which the vocal lines at times sound like a kind of Germanized Bellini. In his first Wagner opera, Viotti succeeds in balancing that unique interplay of opposites that characterizes Wagner's musical world. A world where the sharp edges are softened by coexisting extremes, and where each step is a journey between extremes that embrace each other in a delicate dance of contrasts. His grand gestures (and Instagram account) attest to a certain vanity but conductors who are not vain do not exist (according to the "humble" Bernhard Haitink). In an opera that may be called a musical ode to the inherent beauty of existence, Viotti, backed by a superbly playing Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra, was visibly in his element. Here grand gestures connected with intimate, delicate feelings. As Elsa, emerging here in an iconic vintage headscarf with sunglasses radiating a kind of old Hollywood glamour (Audrey Hepburn!), Malin Byström does not possess the most rounded, gentle voice. As we know from her Salome from a few years ago, her strength lies mostly in the scenes where she can express herself more explicitly. The scene in which she gives voice to her misfortune - half disappearing in her gigantic wedding dress, in analogy to the drama by which she knows herself to be enclosed - is a sonorous visual highlight.. As swan knight, Daniel Behle does not combine his somewhat high tenor with a robust stage personality, as for example the case with Klaus Florian Vogt. With a clean, initially somewhat sharp, tenor voice that, once it arrives at In Fernem Land, shows itself from its most sensitive, versatile side he manages to convince. His Lohengrin is here endowed by the direction with an extra sad fate. He is already a hero against his will. In addition, under the desperate cries of the young woman he has come to the aid of (Mein Gatte! Mein Gatte!), he must pay for his intervention as a lifesaver with death. (Unlike the libretto in which it is the two women, Ortrud and Elsa, who fall down lifeless at the end.) It is a grim end to a demythologizing process that begins to unfold shortly after Lohengrin makes his entrance. As so often, the bad guys are the most fun. Ortrud, the evil genius of the story, and Friedrich von Telramund, who lets himself be taken for a ride by the evil genius, impress the most. Thomas Johannes Mayer, he previously sang Wotan in Amsterdam in the Audi Ring, performs a powerful, evil Telramund. In voice and presentation, Mayer is a character whose heart, insofar as it ever was open, has been hardened by Ortrud into a cold, insensitive core, unreachable for compassion or empathy. A fitting fate befalls him when he sets out to kill Lohengrin by surprise and meets his end himself at the end of the swan knight's sword. Ortrud is of great malicious charm in Martina Serafin's rendition. Her voice sounds a bit harsh on the outer edges but that is entirely in character. Her stage persona is impressive. The scene in which she and her partner in crime Telramund accompany Elsa and Lohengrin to the altar (Telramund on the organ!) is one of great demonic beauty. Here the couple knows that the seed of doubt has been planted in Elsa; its hatching is only a matter of time. The end of the fairy tale is in sight. In the wedding march that follows at the beginning of the third act (a wedding march played only at weddings of people who do not know the story, and its ending - Ha!), bride and groom walk from the back of the hall in procession to the stage. It is the most pronounced part of the staging in which, as mentioned earlier, major choices, essential choices, are absent. Thus we have to do without a bridal bed during the wedding night of Lohengrin and Elsa, and this absence of a compelling direction regarding the many mass scenes causes the stage setting in the scenes with the chorus to be somewhat cluttered at times. Of what König Heinrich must lack in grandeur here in the dressing finds its compensation in the voice of Anthony Robin Schneider who grabs the listener and draws them along in a role performed with regal authority. The nuances in Schneider's voice bring to life a man who shifts from forceful decisiveness to subtle introspection. He is joined in that role by his herald, Björn Burger who again excels (Burger has previously been a very convincing Wolfram in Loy's previous Wagner production, Tannhäuser). Worth a special mention is the chorus of the Dutch National Opera which also comes to great achievements under new chorus master Edward Ananian-Cooper. As a paragon of bleakness, the barren factory hall in which Lohengrin is situated also (unfortunately) models a lack of theatrical imagination. The hall hosts a performance in which singers, orchestra and conductor excel. Against an ash-gray background, a musically colorful landscape imbued with dramatic intensity unfolds. The tones, like vivid brushstrokes, paint a heavenly panorama that challenges and enchants the senses. Gioacchino Rossini once said of Lohengrin (I am writing this review on the anniversary of Rossini's death) that you cannot judge this opera after just one listen, but he certainly had no intention of hearing it a second time! Not free of sarcasm was he, the composer of Il Barbiere di Siviglia. His words will be listened to amicably and elegantly ignored by anyone who wants to spend an immersive evening at the theater (and who doesn't?). There is simply little in the field of opera that compares to a good performance of a Wagner opera. This performance of Lohengrin, despite its flaws, is convincing proof of that. Lohengrin, Dutch National Opera, Amsterdam, 11 November 2023 (premier) Conductor: Lorenzo Viotti Netherlands Filharmonisch Orkest Stage direction: Christof Loy Set design: Philipp Fürhofer Costume design: Barbara Drosihn Lighting design: Cor van den Brink Video design: Ruth Stofer Choreography: Klevis Elmazaj Dramaturgy: Niels Nuijten Heinrich der Vogler: Anthony Robin Schneider Lohengrin: Daniel Behle Elsa von Brabant: Malin Byström Friedrich von Telramund: Thomas Johannes Mayer Ortrud: Martina Serafin Der Heerrufer des Königs: Björn Bürger Chorus of Dutch National Opera Chorus master: Edward Ananian-Cooper - Wouter de Moor

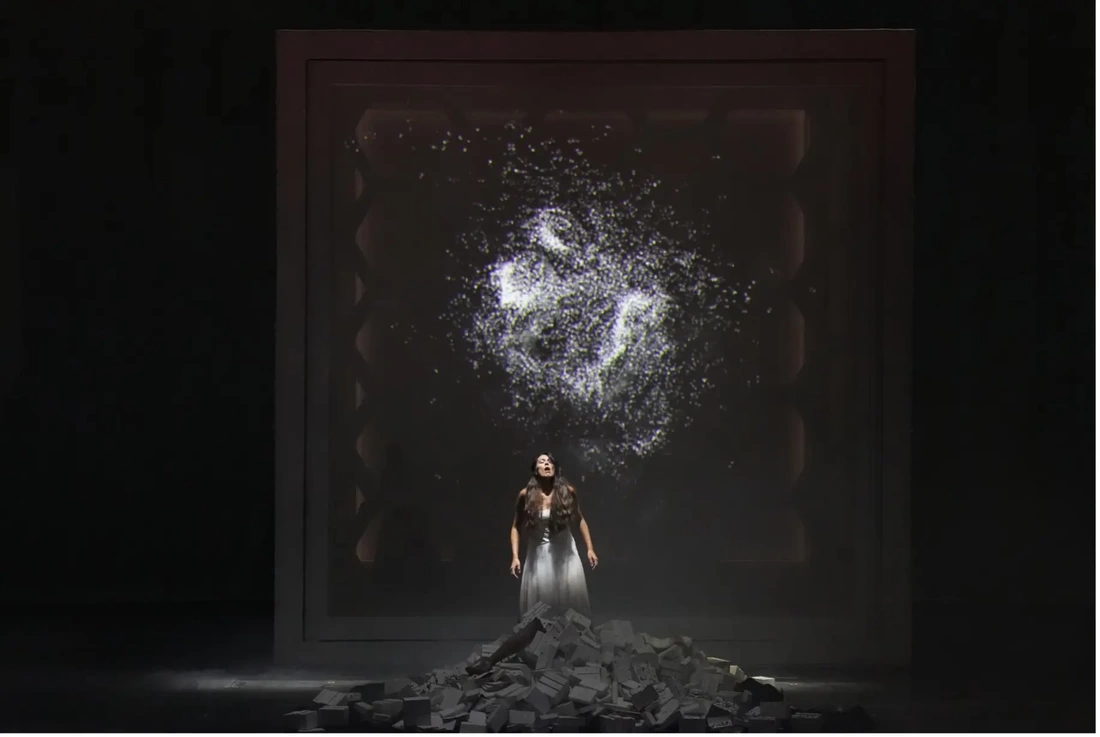

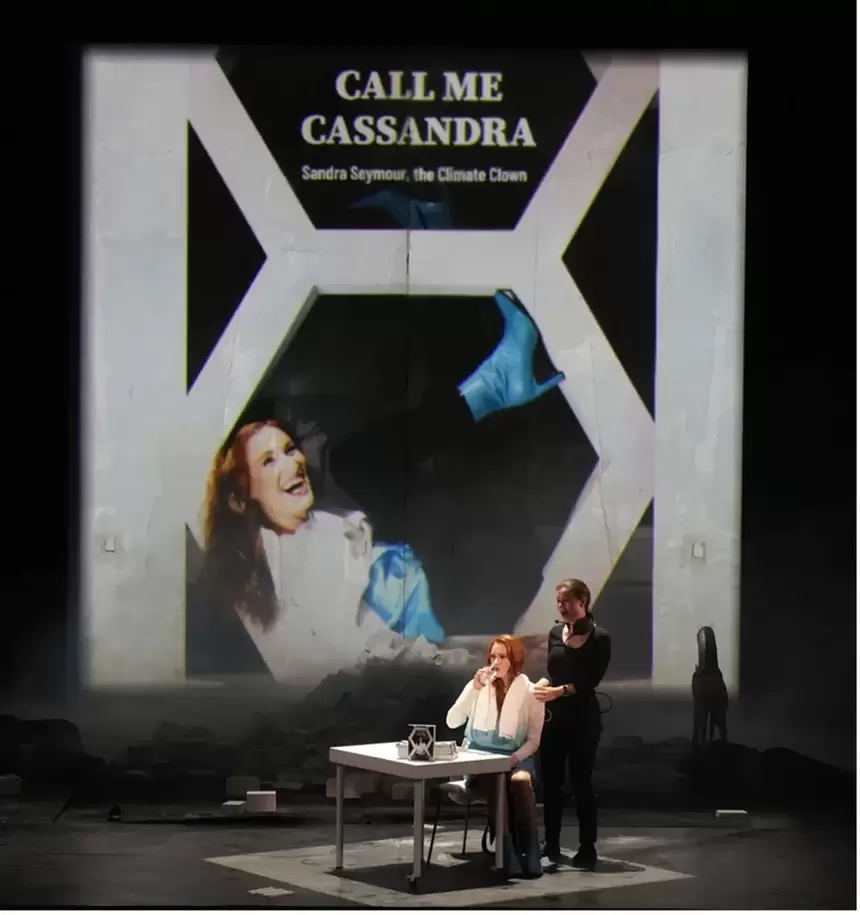

La Monnaie in Brussels opens the new season with a world premiere. In their first opera, Belgian composer Bernard Foccroulle and librettist Matthew Jocelyn touch on a very topical theme: environmental activism and social inertia. About voices that are not heard. The weather was more than appropriate. With 30 degrees in September (we are in the hottest summer ever recorded worldwide), Le Monnaie in Brussels hosted the world premiere of Cassandra, an opera with climate change as its theme. Divided into thirteen scenes, it alternates the story of the Trojan princess Cassandra, whose predictions about the fall of Troy were not taken seriously, with the disbelief that climate scientist Sandra Seymour encounters when she shares her knowledge about the melting of ice caps at the South Pole. In the layers of ice, Sandra sees the past, a past of a warming Earth. With its melting, that view of the past disappears. A past that warns us of the future. The Belgian composer Bernard Foccroulle, also an organist who has previously recorded all of Bach's and Buxtehude's organ works, and until recently was known primarily as a composer of mainly instrumental music, is creating his first opera with Cassandra. An opera with activitism as its theme, which should not be called an activist opera. The opera is a story about voices that are not heard, not believed, with disastrous consequences. Mythology and the present reach out to each other in a musical drama in which Cassandra and Sandra are equals who see each other's story mirrored and amplified across the boundaries of time. With the lamentation of a chorus, which like a Greek choir comments and otherwise not interfere with the action, the story opens. We look onstage at a kind of glacial formation that will also serve as a library, the ancient city of Troy and a beehive. Cassandra stands in the center of the stage in front of a ruin that collapses. Troy is going down, and Cassandra is watching in horror. From the then, of Aeschylos and his play "Agamemnon," we then jump to the present in which climatologist Sandra Seymour performs a one-woman show at the conclusion of a conference on climate change. Blake, a student of ancient Greek language and culture, and a member of a Climate Action group, is annoyed by the light-hearted tone with which Sandra addresses climate issues. Needless to say, love will blossom between Blake and Sandra. In the third scene, we encounter a second, more grim love story. The meeting between Cassandra and the god Apollo. We see Cassandra and Apollo engaged in a fierce dialogue. Apollo gave Cassandra the gift of prophecy in exchange for sex. But Cassandra refuses the reciprocation upon which Apollo spits in her mouth. No one will believe the words that come out of that anymore. These three scenes form the foundation on which librettist Matthew Jocelyn builds in later scenes. These include meetings between Sandra and Blake, a dinner with Sandra's family, a meeting between Cassandra and her father King Priam, who is still struggling with the question of why Troy was destroyed, and a poignant scene in which Naomi, Sandra's younger sister, joyfully looks forward to the birth of her daughter. An event that casts doubt on Sandra about the responsibility of having a child, given the ecological developments. Blake does want a child. A bed scene highlighting the differences between Sandra and Blake on the matter of having children is interspersed with discussions about climate and whether scientific research should be accompanied by climate action. Blake chooses climate action and leaves for the South Pole. In the penultimate, eleventh scene, we once again see Sandra in her one-woman show where she delivers her message. It is her farewell performance, as she has decided to follow Blake in his activism to seize oil tankers. The show is interrupted by someone in the balcony exclaiming, "I came here for stand-up comedy, not an eco-terrorist tirade." During the show, she is told that Blake's ship sank, it is unclear how, perhaps by a torpedo, and that he most likely drowned. Blake's death feels a bit forced - we're in the opera so a protagonist must die. Something like that. In the final scene, Sandra awakens, as if from a traumatic fever dream, and believes she is meeting Cassandra. In a dialogue in which both Cassandra and Sandra long for redemption from their shared misery, Sandra sings that she will not let anyone take away her voice. The identification with her mythological predecessor is complete. With the man on the balcony still in mind, the current state of the public debate and the current times of information inflation, we think of the role of social media that, like a modern many-headed Apollo, spits into the mouths of people, and Sandra here in particular. The duet between Cassandra and Sandra, its introspection, its looking forward to an uncertain future, may count as the opera's highlight. With twelve scenes in two hours and a story in which dramatic progression is at times pending, the opera is an intense sit. As thought-provoking interludes, there are three moments where we see the world-wide bee population dwindling. As the lights on stage slowly dim, only three more bees buzz the opera to its end. Foccroulle envelops his story of the tragedy of voices not heard and warnings not believed with music that both sears and pleases, a music that both intoxicates and sharpens the senses. It is music that refers to that other organist who composed, Olivier Messiaen, and is reminiscent of one of Messiaen's pupils, George Benjamin. But whereas in Benjamin's operas the vocal lines are a natural excerpt from the music over which they meander, Foccroulle's vocal parts sound somewhat mechanical. They often linger in what I shall call melodic declamation, as if the drama behind the words needs to be forcibly sung. In the instrumentation, Foccroulle endows Sandra with a marimba and Blake with a saxophone. A helping hand in following the vocal lines in the dialogues that are sometimes a bit too verbose. Conductor Kazushi Ono, with La Monnaiet's symphony orchestra, pulls the musical arcs of tension considerably taut. Soprano Sarah Defrise excelled as Naomi, Sandra's sister, especially in the lullaby she sang for her unborn child, a lyrical highlight. Jessica Niles gave a spirited interpretation of the character of Sandra Seymour with her firm, clear soprano, and Katarina Bradić, as Cassandra, embodied a woman who is by turns inspired, deficient and desperate. All in all, Cassandra, the opera, succeeds in impregnating topical issues into art. Its music, along with the themes it addresses, resonates as you walk past the European Parliament in Brussels where huge posters bear witness to the most current concerns: the Russian invasion of Ukraine and a desired climate neutrality by 2050. A goal that, for all its good intentions notwithstanding, with the question marks you can place on politics that are not or not sufficiently able to cope with crises, are probably not going to be met. And 2050 is already too late. We hear the unheard voices and the sound of melting ice converge in a roaring silence. Cassandra, La Monnaie, Brussels, 10 September 2023 (world premiere) Music - Bernard Foccroulle Libretto - Matthew Jocelyn Kazushi Ono - Conductor DIRECTION Marie-Ève Signeyrole - Director, Video Artist Fabien Teigné - Set Designer Yashi - Costume Designer Louis Geisler - Dramaturgy CAST Katarina Bradić - Cassandra Jessica Niles - Sandra Susan Bickley – Hecuba, Victoria Sarah Defrise - Naomi Paul Appleby - Blake Joshua Hopkins - Apollo Gidon Saks Priam, Alexander Sandrine Mairesse - Stage Manager Lisa Willems - Conference Presenter - Wouter de Moor

|

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed