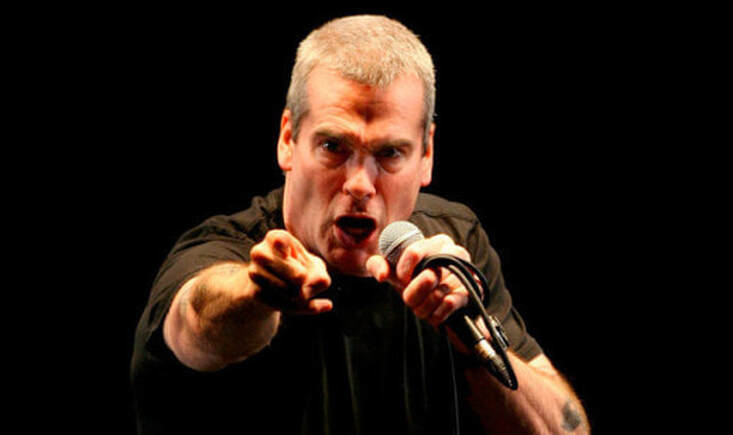

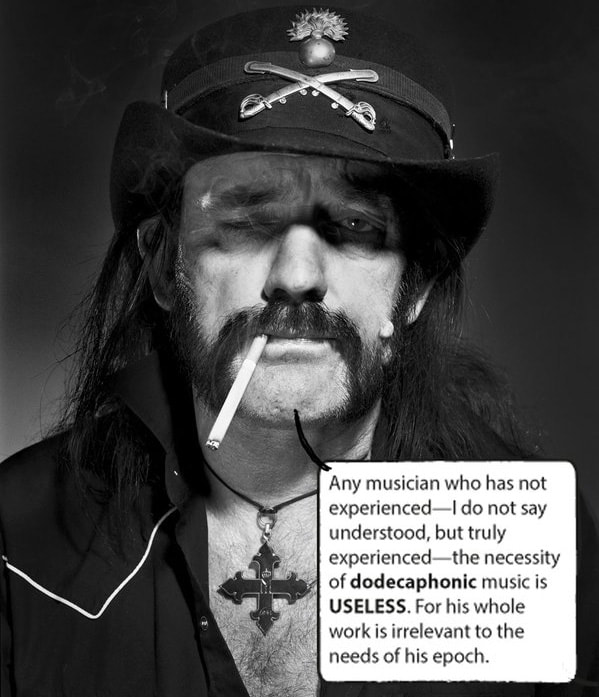

Rollins comes to town and wants you to listen The first time I saw Henry Rollins was in a record store in Eindhoven. In Bullit at Stratumseind a broad-shouldered man, his head slightly bent forward, let his hands go through a CD-tray ( in real life he was smaller than he looked on pictures and videoclips). In every city where he performed, he was the first to browse the local record stores. That was no different now. This was the place he liked to be. He preferred the company of music (and books) to that of people. In the latter he only got disappointed sooner or later. Moreover, he quickly felt uncomfortable in the company of others. And although Henry is now in a better place with himself, these are two things that haven't changed very much. It was the afternoon before a performance of Rollins Band in De Effenaar, now about 20 years ago. The support act had cancelled at the last minute (because they thought the stage was too small or something like that, nobody heard from them since) so the Rollins Band played for an hour longer. Three hours of hardcorish hardcore. The experience was an intense one. He doesn't sing anymore (delivering his words in a kind of hardcore Sprechgesang) - Henry considers himself a pensionado in that field now - but he still talks. Yesterday in Paradiso two hours and 45 minutes non-stop. About America and the hair of Donald Trump, the meaning of David Bowie, the phone call of Lou Reed ("my DNA recognized that voice before my brain did"), punkrock, Motörhead (the only rock band with long hair that deserves the punkrock-seal-of-approval) and the friendship with Lemmy (the first Englishman since Shakespeare who uses the verb "trammel"). Further on about global warming, listening to Raw Power by The Stooges on Antartica while the music barely rises above the sound of mating penguins, about what makes humans resilient and the soundtrack of your life as a basic need. And Henry Rollins strings all that together without taking a single breath. Wow. To what extent he takes the liberty in his, often hilarious, anecdotes to let reality go where the drama or plot line is best served, I don't know. About his meeting with David Bowie ("Rollins!" "David!") he tells that Bowie quotes statements Rollins has made in interviews and he seems to feel uncomfortable with that. Shy of the attention he gets from a rock star he admires, or maybe the fear that he gets caught up in things that have been said that turn out to be contradictory? Did Lemmy really find that tour case in his own room, unopened, after five years? From Rollins, and especially his books "Get in the van (on the road with Black Flag)", "See a grown man cry" and "Black Coffee Blues", I learned that writing can lend itself perfectly for exorcising your own demons and sorting out the mess in your head. "Get in the van" kept me awake at night. That book is like a modern Heart of Darkness; young man leaves his familiar surroundings and searches in the ever changing environment of a band on tour for an anchor in himself. "The irreversibility of one's own choice" should have been the book's subtitle as far as I'm concerned. If you've just left school, are looking for a job and a destination in life, that message hits home. There were days when I hardly dared to touch the book. Afraid of the all-consuming insights that were waiting for me in it. With his natural talent for drama, Henry Rollins always knew how to tell a story. Years later, the founder-guitarist of Black Flag, Greg Ginn, would say disparagingly: "Henry complains a lot. Acting like it was Vietnam or something. You're in a fucking rock band!" On the other hand, Henry thinks Greg doesn't like him because he's more successful. Every artist, including those who have a strong autobiographical approach to their work, eventually adopts a more or less self-mythologizing image of themselves (you don't have to be David Bowie for that). To the total work of art that is life, one like to add some extra colours. It doesn't detract from the gravity of Henry Rollins' spoken words. You stay enthralled for the full duration of the show. All killers and no fillers! Rollins is, even without a band, still hardcore. And the energy of his spoken word performance leaves you in a much better mood than the hour-long exposures to his musical output did. Output in which his lyrics were dressed up with hardcore guitars and drums. Lyrics in which he, as vocalist of Black Flag and Rollins Band, invariably sought the confrontation with himself. A confrontation he often brought beyond the point of redemption. What initially had a liberating effect - the search for a grip and the separation of sense and nonsense - left you eventually without room to breathe and carved the same frown in your forehead as Rollins himself had. "It's that you have to get out of bed early tomorrow morning to go to work (on your bike - respect! - when I take the bike to the nearest supermarket in Los Angeles, I arrive five days later) otherwise I would have talked for seven more hours." And thank you. Talking to him in the end - like rain in August, your line in front of the counter going slower than the line next to you and your rock heroes dying in January - is part of the natural state of things. And we, the audience, watch and hear it with the amazement and admiration that befits witnessing a natural phenomenon. The energy of Hank caused me to need some serious cups of black coffee to wake up the next morning. Falling asleep was somewhat frustrated by the equivalent of the 10 cups of black coffee of words that speech waterfall Rollins had poured in my ears the night before. Where a normal person has a mouth he has a machine gun nest. I needed several Black Coffee Blues moments before I got to work the day after the night before. He may have given the music to it. In addition to spoken word performances, writing, photographing, publishing books and travelling, he sometimes acts in a film. Henry Rollins is very enthusiastic about the film Gutterdämmerung in which he plays a few roles and which will visit pop stages and festivals next summer. The intention is that a live band will perform a soundtrack to the movie. I don't dare to predict if that will be fun any longer than the three minutes this trailer lasts, but it does look, uh, übercool. To conclude with.

1 Comment

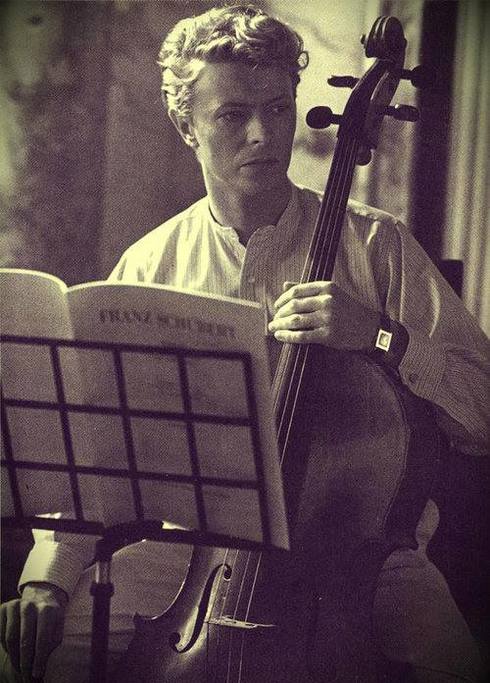

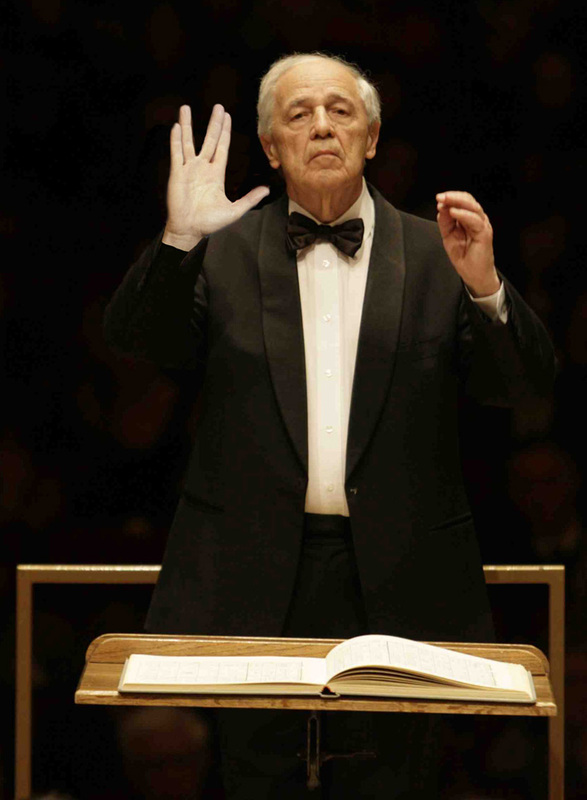

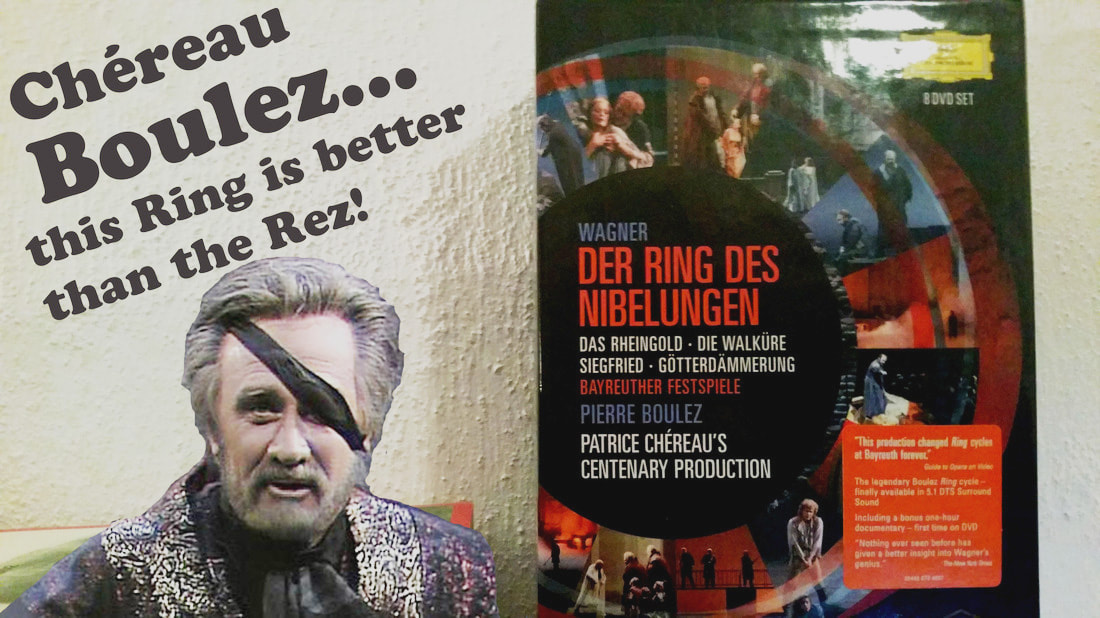

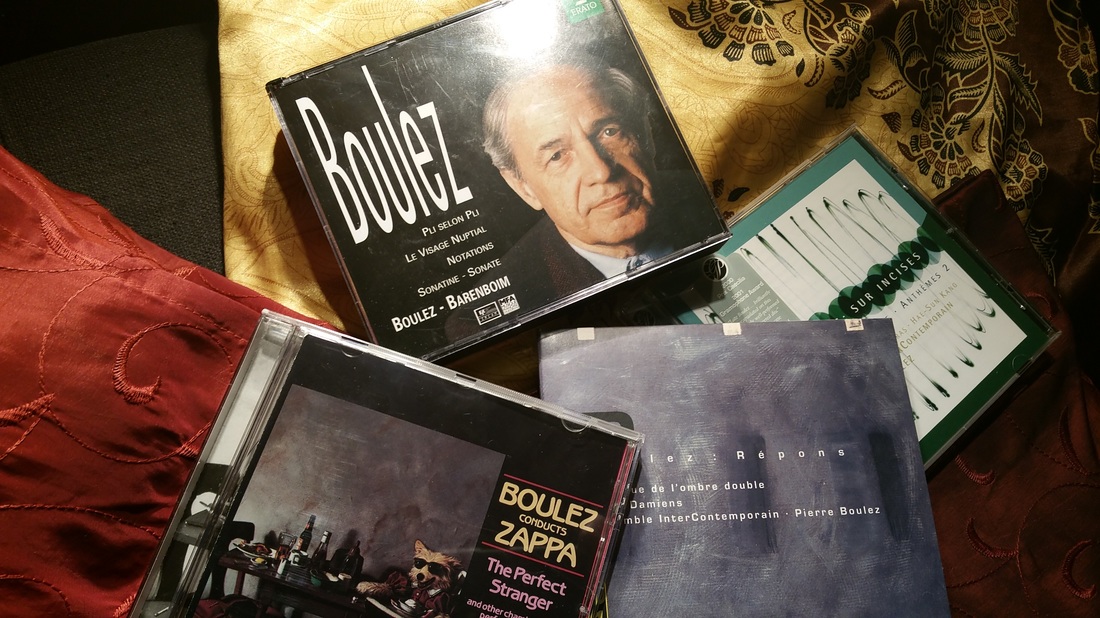

And so we start the new year (and I really hope this is the last time I need to start a blog post this way). But the man Who Fell To Earth and became an elementary part of our musical and cultural lives is not going to join us into 2016 and beyond. That's one reason to be upset (again) because if the ones that are immortal, in life and in image, die anyway, it makes the future for us, the ones who are left behind, just a little bit more unforeseen (again). And so we have, together with Lemmy and Pierre Boulez, within a two-week timeline a trilogy of RIPs. “Staying stuck in the past is stealing from the future”, I have read somewhere. It can be an adage from a man for whom transformation - in image and in music - is not merely a gimmick but a way of living that enables him to keep delving into his own resources. A tool for (creative) survival. From his immense discography I especially cherish Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, Heroes and the first album of his band Tin Machine. Tin Machine didn’t belong to his biggest commercial successes but their first record still hold its ground. In the second half of the 80s the musical expeditions of The Thin White Duke didn’t always set sail to shores of gold. With its self-titled debut album in 1989 Tin Machine was a, highly welcomed, departure from some of the less than memorable things Bowie had done in the time prior (I don’t want to hear “Tonight”, a duet with Tina Turner, ever again). It was the era of grunge, the time of back-to-basic raw guitar sounds, but with the teenage angst from Cobain en co. Tin Machine had nothing to do. For that David Bowie was, as ever, too self conscious and too well dressed (also as a singer of a rockband). I will give this record another spin at high volume these days. After the Motörhead-sessions on 29 December (No Sleep Till Hammersmith on repeat) and last week’s two days of Pierre Boulez (his own orchestral works one day and Bayreuther Ring-recordings from 1976 the other day) I’m sure my neighbours will thank me for that. The chameleon of pop has transformed for the last time. Creativity has its final word over irony when a record on which he sounds rejuvenated (Blackstar) now seems to be his requiem. And so we start the new year. But the man I always thought would live to see 100 is not going to join us into 2016 and beyond. That's one reason to be upset, among others, because if the ones that were with us for such a long time, in life and in image, die anyway, it makes the future just a little bit more unforeseen (and insecure). With his demise the 20th century is definitely over and the 21th century has lost another burden of its past. I guess Pierre Boulez would not be unsympathetic towards that idea. Creation exists only in the unforeseen made necessary, he once said. For someone who was nicknamed “Mr. Sang Froid” his contributions to the late 19th-begin 20th century German-Austrian romantic repertoire were remarkable. It was Richard Wagner's Ring des Nibelungen that introduced me to Pierre Boulez. His reading of Wagner, swift and transparent, convinced me at once. In Wagner there is a risk to state the obvious. Then the tempi slow down and the volume increases. Not with Boulez. With him Wagner's music is like a cathedral drawn in fine lines that gives us a view of the structure that lies underneath – a sense for superb architecture. His Wagner was alive and breathing, as was his Mahler and Bruckner. For someone whose nicknames went from “Mr. Sang Froid” to “The high priest of modern music”, his contributions to the late 19th-begin 20th century German-Austrian romantic repertoire were remarkable. From his performances in Bayreuth I have Parsifal (1970), Der Ring des Nibelungen (Cds from 1976 and 1977 and DVDs from 1980) and a performance from Tristan und Isolde from 1969 (recorded in Osaka Japan, this is a Bayreuth on Tour-production). The 1976 Ring is special. It was Boulez' take on the music together with Chéreau's regie that was too much of a breach in the tradition of Wagnerian opera performances than the audience was willing to accept for this centenary Ring. Among booing and other noisemaking, that indicates that a considerable part of the audience is less than amused, there is in Siegfried someone from the anti-Chereau contingent who brings his own whistle. In the saddest tradition of the Jockey Club, a prestigious elite club that terrorized Wagner's Paris premiere of Tannhäuser in 1861, he plays along when Siegfried blows on his own makeshift reed in the second act. There is a frenzy that surrounds these performances and it makes listening to them both exciting and harrowing. A frenzy that I miss, perhaps odd, in the recordings from 1977 (the 1980 performances on DVD were, of course, recorded without audience). With Patrice Chéreau already dead in 2013, both director and conductor of this legendary Ring are no more. It was in vain that Boulez asked Chéreau to look into Parsifal. But Chereau couldn't connect to this opera and declined. Alas. It was Boulez who made a case for Parsifal for me. Because for a long time I had a pretty hard time digesting Wagner's last opera. I've read about the life-changing event the Knappertsbusch-1951-performance must have been but from the long first act (which can be slower-than-slow) to the intoxicating end of the third act, I felt, in contrary to all those other Wagner operas (from Holländer on), an uninvited guest at a party where only initiates were welcome. It was not before I heard Boulez' take on Parsifal, with his swift tempi, that this opera started to make sense to me.

The last time I saw Boulez was in Amsterdam, the Concertgebouw. It was Januar 2011, now exactly 5 years ago and he conducted Mahler 7 on that occasion. He linked Gustav Mahler to Six Pieces for Orchestra by Anton Webern. By programming it that way, and by his crystal clear reading, he showed us Mahler as a 20th century composer. Away from the 19th century - away from Bruckner and Brahms. He refreshed my view on Mahler like he did with Wagner before. Boulez was a door to new music. Be it as an interpreter of compositions by Frank Zappa (one way to describe Zappa's efforts in modern composition is "Boulez-lite with a beat", I leave it to the academics to what degree that description is apt) or by his own compositions which I came to know and appreciate pretty late in my music-loving life (with Pli Selon Pli, Le Visage Nuptial, Répons and the hauntingly beautiful Cummings ist Der Dichter as current favorites). Like all great art, Boulez' music is accessible on different levels. You don't have to be a scholar in musical theory in order to appreciate it. Put on a record and just let it happen. It will grow on you (often habituation precedes appreciation). The only thing you need is a body and a pulse (I think Wagner said something like that when he was confronted with concerns about the accessibility of Tristan und Isolde - 4 hours of heavy chromatic music in an opera without any arias). And ears that grew up with movie soundtracks know how to deal with dissonances and enharmonic sounds a lot better than you will, perhaps, give them credit for. Pierre Boulez had a good taste for polemic but for me he was, first and foremost, a bridge to new worlds of sound. For that I'm grateful. Merci maître. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed