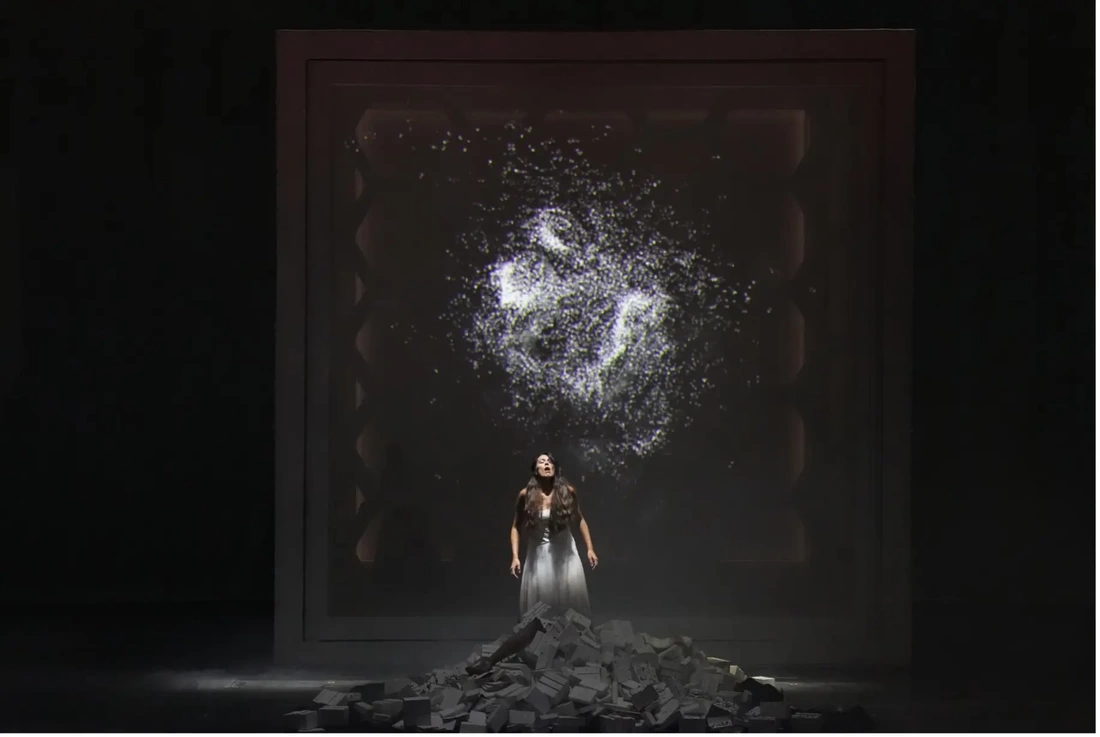

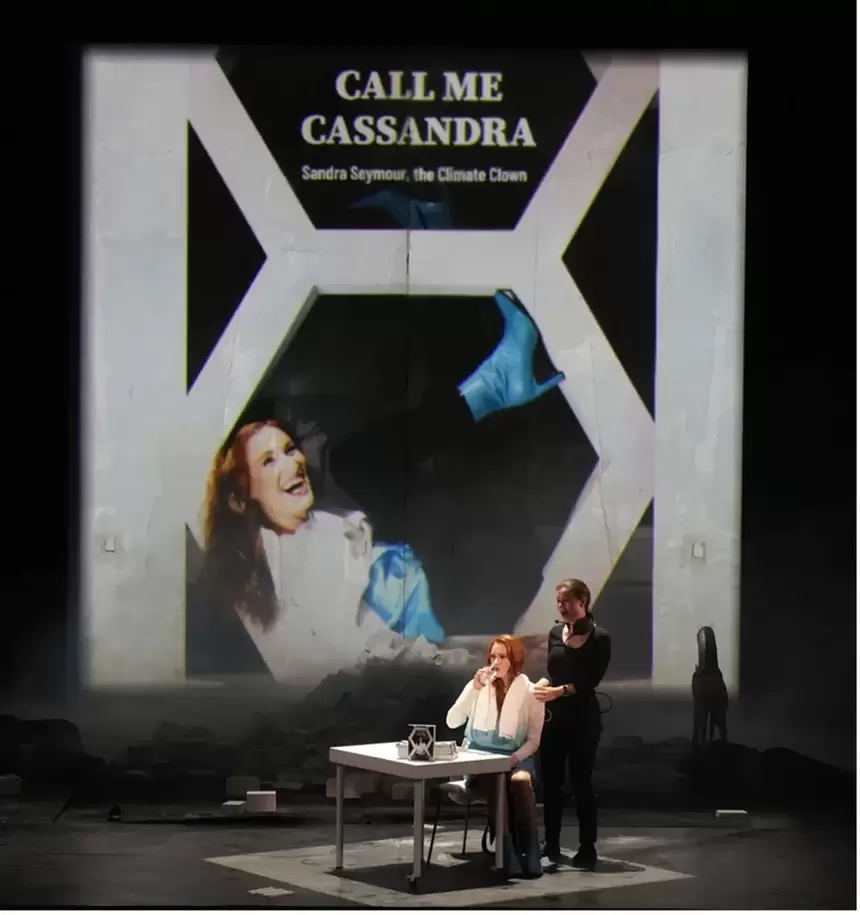

La Monnaie in Brussels opens the new season with a world premiere. In their first opera, Belgian composer Bernard Foccroulle and librettist Matthew Jocelyn touch on a very topical theme: environmental activism and social inertia. About voices that are not heard. The weather was more than appropriate. With 30 degrees in September (we are in the hottest summer ever recorded worldwide), Le Monnaie in Brussels hosted the world premiere of Cassandra, an opera with climate change as its theme. Divided into thirteen scenes, it alternates the story of the Trojan princess Cassandra, whose predictions about the fall of Troy were not taken seriously, with the disbelief that climate scientist Sandra Seymour encounters when she shares her knowledge about the melting of ice caps at the South Pole. In the layers of ice, Sandra sees the past, a past of a warming Earth. With its melting, that view of the past disappears. A past that warns us of the future. The Belgian composer Bernard Foccroulle, also an organist who has previously recorded all of Bach's and Buxtehude's organ works, and until recently was known primarily as a composer of mainly instrumental music, is creating his first opera with Cassandra. An opera with activitism as its theme, which should not be called an activist opera. The opera is a story about voices that are not heard, not believed, with disastrous consequences. Mythology and the present reach out to each other in a musical drama in which Cassandra and Sandra are equals who see each other's story mirrored and amplified across the boundaries of time. With the lamentation of a chorus, which like a Greek choir comments and otherwise not interfere with the action, the story opens. We look onstage at a kind of glacial formation that will also serve as a library, the ancient city of Troy and a beehive. Cassandra stands in the center of the stage in front of a ruin that collapses. Troy is going down, and Cassandra is watching in horror. From the then, of Aeschylos and his play "Agamemnon," we then jump to the present in which climatologist Sandra Seymour performs a one-woman show at the conclusion of a conference on climate change. Blake, a student of ancient Greek language and culture, and a member of a Climate Action group, is annoyed by the light-hearted tone with which Sandra addresses climate issues. Needless to say, love will blossom between Blake and Sandra. In the third scene, we encounter a second, more grim love story. The meeting between Cassandra and the god Apollo. We see Cassandra and Apollo engaged in a fierce dialogue. Apollo gave Cassandra the gift of prophecy in exchange for sex. But Cassandra refuses the reciprocation upon which Apollo spits in her mouth. No one will believe the words that come out of that anymore. These three scenes form the foundation on which librettist Matthew Jocelyn builds in later scenes. These include meetings between Sandra and Blake, a dinner with Sandra's family, a meeting between Cassandra and her father King Priam, who is still struggling with the question of why Troy was destroyed, and a poignant scene in which Naomi, Sandra's younger sister, joyfully looks forward to the birth of her daughter. An event that casts doubt on Sandra about the responsibility of having a child, given the ecological developments. Blake does want a child. A bed scene highlighting the differences between Sandra and Blake on the matter of having children is interspersed with discussions about climate and whether scientific research should be accompanied by climate action. Blake chooses climate action and leaves for the South Pole. In the penultimate, eleventh scene, we once again see Sandra in her one-woman show where she delivers her message. It is her farewell performance, as she has decided to follow Blake in his activism to seize oil tankers. The show is interrupted by someone in the balcony exclaiming, "I came here for stand-up comedy, not an eco-terrorist tirade." During the show, she is told that Blake's ship sank, it is unclear how, perhaps by a torpedo, and that he most likely drowned. Blake's death feels a bit forced - we're in the opera so a protagonist must die. Something like that. In the final scene, Sandra awakens, as if from a traumatic fever dream, and believes she is meeting Cassandra. In a dialogue in which both Cassandra and Sandra long for redemption from their shared misery, Sandra sings that she will not let anyone take away her voice. The identification with her mythological predecessor is complete. With the man on the balcony still in mind, the current state of the public debate and the current times of information inflation, we think of the role of social media that, like a modern many-headed Apollo, spits into the mouths of people, and Sandra here in particular. The duet between Cassandra and Sandra, its introspection, its looking forward to an uncertain future, may count as the opera's highlight. With twelve scenes in two hours and a story in which dramatic progression is at times pending, the opera is an intense sit. As thought-provoking interludes, there are three moments where we see the world-wide bee population dwindling. As the lights on stage slowly dim, only three more bees buzz the opera to its end. Foccroulle envelops his story of the tragedy of voices not heard and warnings not believed with music that both sears and pleases, a music that both intoxicates and sharpens the senses. It is music that refers to that other organist who composed, Olivier Messiaen, and is reminiscent of one of Messiaen's pupils, George Benjamin. But whereas in Benjamin's operas the vocal lines are a natural excerpt from the music over which they meander, Foccroulle's vocal parts sound somewhat mechanical. They often linger in what I shall call melodic declamation, as if the drama behind the words needs to be forcibly sung. In the instrumentation, Foccroulle endows Sandra with a marimba and Blake with a saxophone. A helping hand in following the vocal lines in the dialogues that are sometimes a bit too verbose. Conductor Kazushi Ono, with La Monnaiet's symphony orchestra, pulls the musical arcs of tension considerably taut. Soprano Sarah Defrise excelled as Naomi, Sandra's sister, especially in the lullaby she sang for her unborn child, a lyrical highlight. Jessica Niles gave a spirited interpretation of the character of Sandra Seymour with her firm, clear soprano, and Katarina Bradić, as Cassandra, embodied a woman who is by turns inspired, deficient and desperate. All in all, Cassandra, the opera, succeeds in impregnating topical issues into art. Its music, along with the themes it addresses, resonates as you walk past the European Parliament in Brussels where huge posters bear witness to the most current concerns: the Russian invasion of Ukraine and a desired climate neutrality by 2050. A goal that, for all its good intentions notwithstanding, with the question marks you can place on politics that are not or not sufficiently able to cope with crises, are probably not going to be met. And 2050 is already too late. We hear the unheard voices and the sound of melting ice converge in a roaring silence. Cassandra, La Monnaie, Brussels, 10 September 2023 (world premiere) Music - Bernard Foccroulle Libretto - Matthew Jocelyn Kazushi Ono - Conductor DIRECTION Marie-Ève Signeyrole - Director, Video Artist Fabien Teigné - Set Designer Yashi - Costume Designer Louis Geisler - Dramaturgy CAST Katarina Bradić - Cassandra Jessica Niles - Sandra Susan Bickley – Hecuba, Victoria Sarah Defrise - Naomi Paul Appleby - Blake Joshua Hopkins - Apollo Gidon Saks Priam, Alexander Sandrine Mairesse - Stage Manager Lisa Willems - Conference Presenter - Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

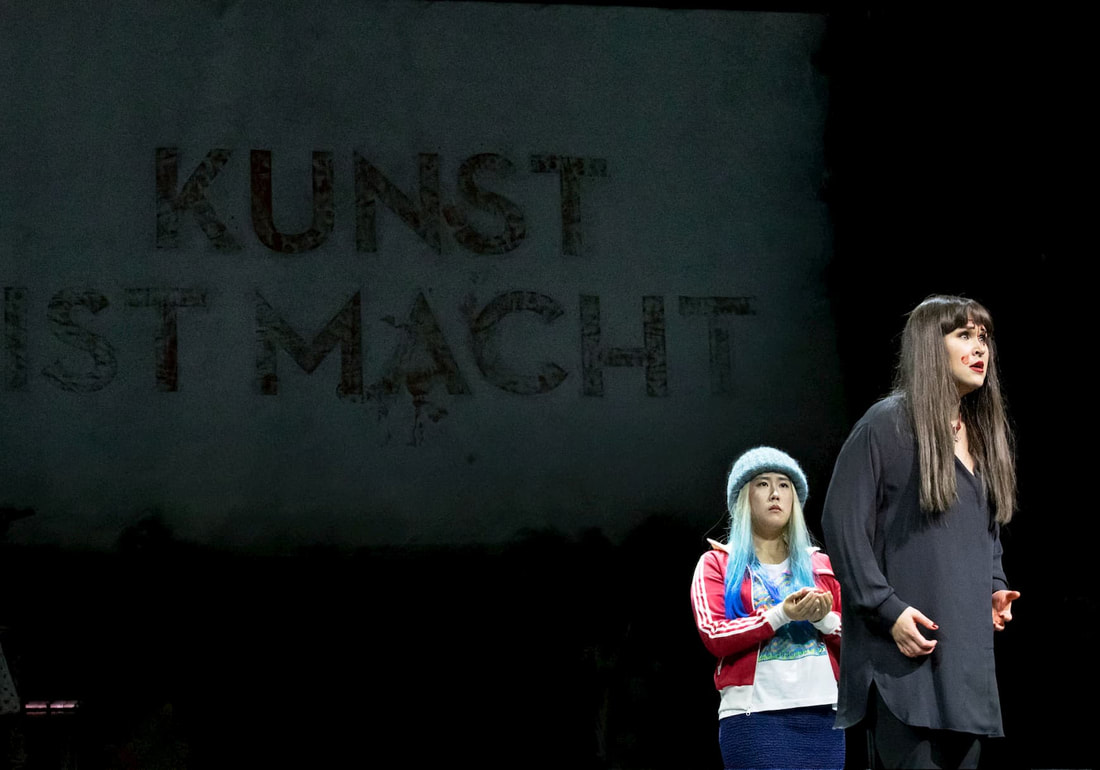

Opera Vlaanderen opens the new season with Milo Rau's production of Mozart's La Clemenza dit Tito. A performance in which Rau unleashes his "theater of reality" on Mozart's last opera, creating two performances in one. A performance of Mozart's opera on the one hand and that of the director's story on the other. A schizophrenic production that will undoubtedly split minds. Mozart composed La Clemenza di Tito just before his death, in a time frame of 3 months (there is even mention of 18 days, it was a rush job anyway) on the occasion of the coronation of Leopold II. The commission paid well, twice the amount one usually paid in Vienna for an opera, and that was not unwelcome for the composer in need of money. Because of that short time, no new libretto could be written so a libretto by Metastasio was adapted that was already half a century old at the time. Tito was an opera that served a political purpose and (therefore) was nailed in its time. Moreover, the form, the opera seria, was considered increasingly obsolete by the end of the 18th century. It may have been a more or less forgotten opera in Mozart's repertoire for a long time, but La Clemenza di Tito has since enjoyed popularity. For example, Tito's forgiveness inspired American theater producer Peter Sellars to create a production about coexisting in a modern society and, without attempts at updating, the opera appears to be able to stand on its own musical feet enough to justify concert performances. Milo Rau, theater maker and self-proclaimed revolutionary, ventures into his first opera with La Clemenza di Tito and begins its production with a kind of apology for it. An opera composed two years after the French Revolution in honor of a king. An opera that provides the nobility, the elite, with an areole of magnanimity. Rau has something to say about that. That is not only suspicious, that is morally reprehensible. That elite, the bourgeoisie, is only out to perpetuate its own power and maintain the status quo. It was so in the late 18th century and it is so now. The elite is disingenuous, its motives cannot be trusted. Tito's forgiveness is questioned by Rau. He turns the king into a man with narcissistic and neurotic traits, giving his texts ironic overtones and making them the words of an unreliable narrator. Rau turns Tito's court into an art gallery, a place where the king has his work applauded by his compliant entourage. That hip world is in sharp contrast to a refugee camp outside which is in a desolate state and where, as part of "law and order," people are being arrested. We witness an execution. All in the name of the king. Does the "merciful" Tito himself believe what he says? Rau deletes extensively in the recitatives of the original and cuts up the opera. After the overture, we move from court to refugee camp. We hear music from a ghetto blaster, a man (calling himself the last man from Antwerp) makes a speech about the city that has changed beyond recognition during his lifetime. His heart is cut out (literally). By then it has become unequivocally clear that Rau is not so much concerned with Mozart and his opera as with the story he himself has to tell. Mozart's Tito is merely instrumental to that story. A story about the elite imposing its will on the people and using art in the process to keep the people quiet. Art as opium for the people. "Kunst ist macht" we read on a video screen (why in German? I fear there is a, by now, worn-out reason behind it). Art, its capitalization, channels revolutionary thought, ensures that what is dreamed about does not become a reality. The king and his entourage are therefore artists or manifest themselves as such. Thus Tito is a painter and Vitellia presents herself as a kind of Marina Abramovich. All this under the nowadays inevitable presence of a cameraman on stage. (The last five operas I saw all had a cameraman onstage; is this current streaming-on-stage trend the first real theatrical legacy of the Covid period when (laptop) camera and screen proved indispensable tools if we wanted to see a performance and/or our fellow human beings?) Further, the question that arises here is: Are we, as audience in the theater, not both elite (bourgeoisie who benefit from the status quo) and common people (who see the arts as narcotic entertainment) at the same time? Rau illustrates the story of the opposition between elite and people, between man and his dreams, through clips of people who have sought refuge in Belgium. The performance thus squeezes two performances into one. Mozart's opera on the one hand and the director's story on the other. We see short biographical clips of singers that are a sort of behind-the-scenes footage while the performance continues onstage. We learn, for example, that Anna Goryachova (Sesto, here not a trouser role but 'just' a woman in a female role) is in real life a mother with child (with attendant worries). It creates Brechtian alienation, and a meta-effect, when she, as Sesto, gives evidence of her torned feelings toward Tito. Initially the two worlds of this performance, that of the director and that of Mozart's opera, have something to say to each other but gradually they let go of each other entirely. Then the story of the opera is no longer directed and we listen to beautiful arias that have then become a kind of soundtrack for documentary footage. The sincerity of those images about people telling about their personal history notwithstanding, they lose power toward the end - there is image inflation. One could almost see in it a plea for a concert performance; the music can stand perfectly well on its own when the director has apparently run out of ideas. As a theater production, this Tito definitely has its moments where Rau makes his point in a haunting way. As a staging of an opera, the result is somewhat poor. For that, the opera is too much of a vehicle rather than a grid to start from. It does not help that the story Rau wants to tell does not develop (it is fairly quickly clear what he wants to say) and that the texts projected on stage leave an increasingly pubescent impression towards the end. The elite, the bourgeoisie, is presented here as an undefined homogeneous bloc. Who are the Titos in today's world? What exactly does the desired radical change entail? It remains unclear. As a director in an opera house, the bastion of the establishment, Rau shows himself a bit like a teenager in a Che Guevara t-shirt. A young man who, in the safety of his room, abandons himself to romantic ideas of revolution. This production of La Clemenza di Tito deconstructs Mozart's opera and will undoubtedly split minds. But couple (stage) image to music and the music will prevail. Indeed, that music does its job and this Tito is carried by a fantastic cast and excellent musicians. Alejo Pérez gives lead to an inspired playing orchestra. Jeremy Ovenden plays and sings the role of Tito as Rau conceived it with conviction. The aforementioned Anna Goryachova excels, both in acting and singing, as Sesto. Anna Malesza-Kutny appropriately brings Vitellia to the brink of madness and Sarah Yang sings a very beautiful, sensitive Servillia. Of the "ordinary people" that Rau, following his own tradition, brings to the stage, the last man from Antwerp deserves a special mention. His biographical clip reveals that he holds no less than 70 different versions of Parsifal (and now, of course, we want to know which version is his favorite). © Annemie Augustijn Toward the end of the performance, a young man announces in a video his coming-out as bisexual, citing a city as a place where ideas have sex with each other. One could say, with that metaphor in mind, that this La Clemenza di Tito is a production in which Milo Rau courts Mozart but does not let it come to an intimate union. He goes his own way, eventually leaving Mozart to it. La Clemenza di Tito, Antwerp 10 September 2023 Perfromances: 10-Sept until 26-Oct (in Antwerp, Ghent & Luxembourg) Conductor: Alejo Pérez Regie: Milo Rau CAST Tito: Jeremy Ovenden Vitellia: Anna Malesza-Kutny Sesto: Anna Goryachova Annio: Maria Warenberg Servillia: Sarah Yang Publio: Eugene Richards III CHOIR & ORCHESTRA Koor Opera Ballet Vlaanderen Symfonisch Orkest Opera Ballet Vlaanderen - Wouter de Moor

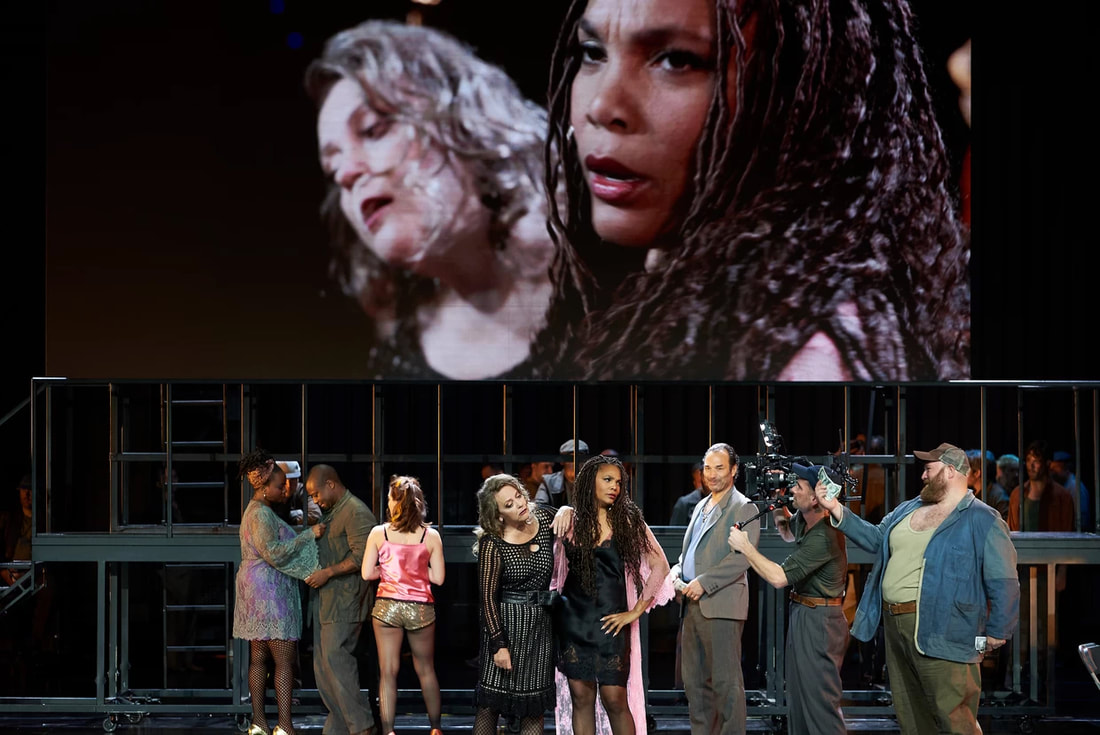

After his 2017 production of Salome, Ivo van Hove returns to The Dutch National Opera with Kurt Weill's "Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny. After his successful Salome (2017), Ivo van Hove returns to The Dutch National Opera with Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny. That return was postponed for three years because the originally planned performances of this production were cancelled in 2020 due to the Covid lockdown. Last year this production was seen at Opera Vlaanderen. Now The Dutch National Opera is opening the new 2023/2024 season with it. In the barren sands of Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht piece together a dystopian story in which man feasts on excess and gives in to primal urges. We see a stage with a large video screen. That's where it all happens. There we see how the city of Mahagonny is founded, becomes a place for all sorts of excesses and finally goes up in flames. Unlike previous opera productions by Van Hove, where the use of video images was often superfluous and gratuitous (Schreker's Der Schatzgräber for DNO!), the use of camera images, video projections and green screens in this production finds a justification within a set-up in which the stage becomes a place in which reality and illusion complement and challenge each other. A reality in which anything goes. A reality that is stripped of its illusions when not having money turns out to be punishable by death. The excesses of Mahagonny find a frenzied imagination in the excessive use of video. On a green screen, ultimum of the illusion in which man loses himself, someone is beaten to death in a boxing match, a line of men can be seen taking a prostitute from behind. These are images that leave little to the imagination, that alternately impress, depress and flatline. Images that, through their lavish use, emphasize the emptiness behind them but also make you wonder if the visual excess does not harm at some point. That the head, deliberately placed above the heart by Brecht, is not pushed away too much by the visual splendor that ultimately has a hypnotic and narcotic effect. The use of video on stage can now no longer be called new, although Van Hove still seems to be searching for the limits of its possibilities; the presence of a cameraman on stage is a fairly recent phenomenon. Social media have found its way to the theatrical stage and, since the Covid period, have hardly been absent. In the last five operas I saw, there was a cameraman walking around on stage whose recordings were projected onto a video screen. Reality recorded by cameras as an indispensable component of experienced reality. Mahagonny here gets an opera cast with an impressive track record. Evelyn Herlitzius, well-versed in Wagner and Strauss and Nikolai Schukoff (he previously sang the title role of Lohengrin at DNO) are, respectively, the con artist Leokadja Begbick and Jim Mahoney, the man who finds out that an empty wallet literally means the end. Herlitzius has never lacked expression; in addition to her singing, she has always had to depend to a not inconsiderable degree on her acting. In a role where acting is more important than the beauty of a voice, she is perfectly in place (I couldn't escape thinking of Elektra at her occasional outbursts). Nikolai Schukoff, together with Lauren Michelle's Jenny, forms a radiant centerpiece of a love that is, very opera-tesque, doomed. Lauren Michelle sings a beautiful role with which she poignantly colors her desires but at times its deeply human impact, along with the rest of the production, seems to fade into the digital oasis that is Mahagonny. That a production of a play that addresses the emptiness of excess sometimes gets itself caught up in the drive for technological splendor is not without irony. The story revolving around the seduction and perversion of ideals through greed for money finds a compelling performance with an excellent cast and fine orchestra. The Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Markus Stenz, a specialist in 20th-century repertoire, adeptly discharges its duty to bring Weill's musical world with elements of ragtime, jazz and tango to life with rhythmic alertness. Orchestra and singers, in connection with the dystopian story they tell, form a harmonious whole. The Chorus of Dutch National Opera effortlessly switches between a cappella and a quasi-Slave Chorus. They contribute, in no small way, in bringing Weill's musical world alive. In Mahagonny's predecessor Dreigroschenoper, it was said that the common man cannot care about morality until he has food (Erst kommt das Fressen, dann kommt die Moral). In Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, that adage is expanded into the motto of a city, a place where anything goes, provided it is paid for. "Erstens, vergeßt nicht, kommt das Fressen Zweitens kommt der Liebesakt. Drittens das Boxen nicht vergessen Viertens Saufen, laut Kontrakt. Vor allem aber achtet scharf Daß man hier alles dürfen darf.” The politically-satirical comments on capitalism continue to resonate especially today. With songs that have made it into pop music, the Alabama Song (The Doors) Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny along with its bristling and haunting music can be considered a unique amalgam of extremes. A musical theater that, in this production, is not so much a paragon of Brechtian alienation but rather characterized by an overwhelming of the senses. A production that reminds us with its exorbitant use of resources that it is often the simple gesture that leaves the deepest impression and to which the concluding oratorio-like chorus makes it known that for real drama, even when human degeneration reaches a nadir, real beauty is indispensable. Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (Kurt Weill & Bertolt Brecht), Muziektheater Amsterdam 9 September 2023 Conductor: Markus Stenz Regie: Ivo van Hove Decor & light: Jan Versweyveld Costums: An D’Huys Video: Tal Yarden Dramaturgie: Koen Tachelet Leokadja Begbick: Evelyn Herlitzius Fatty: Alan Oke Dreieinigkeitsmoses: Thomas Johannes Mayer Jenny Hill: Lauren Michelle Jim Mahoney: Nikolai Schukoff Jack O’Brien/Tobby Higgins: Iain Milne Bill: Martin Mkhize Joe: Mark Kurmanbayev* Sechs Mädchen von Mahagonny Viola Cheung, Thembinkosi Magagula, Elisa Soster, Raphaële Green, Kadi Jürgens, Jessica Stakenburg * Dutch National Opera Studio Chorus of the Dutch National Opera Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra Coproductie with Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, Metropolitan Opera, Opera Ballet Vlaanderen & Grand Théâtre de Luxembourg - Wouter de Moor

|

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed