|

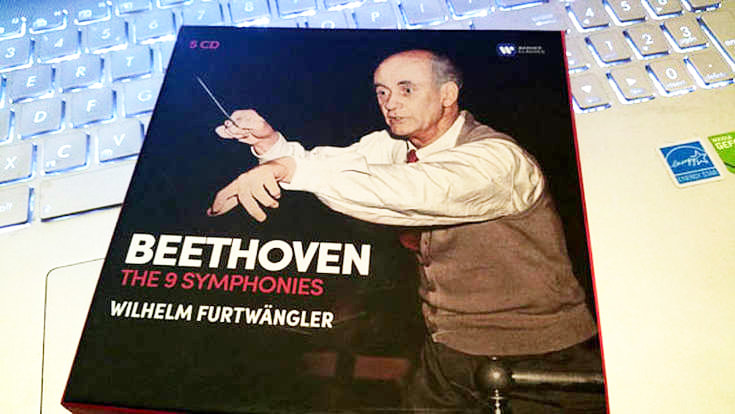

In this time of year, when hibernation tendencies seem to take over, I respond to the music of Beethoven in the most starkest of ways. Be it string quartets, piano sonates or symphonies, Beethoven's music is a road to spring and an answer to questions I didn't even know I had. When it comes to Beethoven I'm not so much of a completist; Karajan and Toscanini are not in my symphony cycle collection for instance. Depicted below are the symphony cycles that are, currently, on my shelves. On the birthday of Ludwig this is a quick inventory of them: Roger Norrington - The London Classical Players (studio 1986-88): Refreshing when I first heard it. Transformed Beethoven from a self-confident man into a man full of doubts who was, literally, on the run. As if he had to catch the last train. The more I listened to it, the more Norrington's obsession with Beethoven's metronome markings and aversion to string vibrato shone through. At the expense of my listening experience. Jos van Immerseel - Anima Eterna (live 2005-2007): The term Sturm und Drang couldn't be more appropriate than for these versions of Beethoven's Mighty Nine. This is Beethoven the revolutionary, fighting the musical consensus of his time. I saw this orchestra playing the 7th and the 8th symphony. It squeaked, creaked and sighed. This was not a majestic Beethoven but a Beethoven who was not afraid to get his hands dirty. During the concert there was a resemblance, not with another classical orchestra or another piece of classical music but with Jimi Hendrix. An artist who was not only fighting with musical boundaries but also with the instrumental means that were at his disposal. With the raw, abrasive sound of violins, wood wind and brass producing their own acoustic feedback, dating from a time before the invention of amplified sound and speaker cabinets, Immerseel and Anima Eterna pushed Beethoven out of his comfort zone and did him justice as one of the most groundbreaking composers that ever was. Theories about historical performance practices rarely convince. The music has to do that and it does here in a superb way. Frans Bruggen - Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century (studio & live 1988-1997): Another historical performance Beethoven. Sounds much more mature (not necessarily a virtue) than Immerseel. With Bruggen, Beethoven is less of a revolutionary and more an arrived man. Has the best version of the 9th symphony with period instruments I've heard. Herbert Blomstedt - Staatskapelle Dresden (church 1976-1980): One of my first cycles because of its low price. A good buy for your buck: good sound and well executed. With Blomstedt, Beethoven is someone who won't upset anyone. Decent but this readings stay a bit on the dull side of things. André Cluytens - Berliner Philharmoniker (studio 1958): For a long time my favorite cycle. In good 50's sound. As in his Wagner recordings, Cluytens is a conductor who mostly lets the music take care of itself. Like Clemens Krauss, André Cluytens gives me the feeling that the music can't be played in any other way. His approach is organic, has nothing artificial in it, and the result is completly self-evident. Carl Schuricht - Paris Conservatoire Orchestra (studio 1957-58) From the same era as Cluytens comes another favorite of mine. Having said that: this cycle is in the suitcase for the proverbal desert island. In the field of different approaches (HIP or modern) and their underlying philosophies, Schuricht does not seem to care (too much) about the choice of given instruments. His French conservatory orchestra plays with French-style woodwind and brass, making this cycle sound different than any other. It's not an objection at all. Schuricht's direction is to the point, with a keen ear for detail, and he does justice to Beethoven the revolutionary. With modern instruments in a musical delivery that unites the vibrant of HIP and the grandeur of the romantics this is, despite the mono sound for symphonies 1 to 8, the best of both worlds. Osmo Vänskä - Minnesota Orchestra (studio 2004-2006): I bought this cycle after a concert in which conductor and orchestra played the fifth symphony (my first ta-ta-ta-taaaa live!). Perhaps the biggest letdown of the whole series of cycles that are mentioned here. Here Beethoven's symphonies are presented like collections of isolated moments, notes even, rather than coherent strings of musical ideas. Whatever Vänskä's intentions or philosophies are (the use of the Ur-text suggests a HIP-invoked approach), the result leaves me stone cold. With a modern, big orchestra sounding jumpier than the worst kind of HIP (it's plagued by a complete lack of legato), this cycle can be considered as the worst of both worlds. Christian Thielemann - Wiener Philharmoniker (live 2008-2010): As Karajan's protégee Thielemann sings in his master's voice. Majestic with tones sculpted in ivory. The beauty of all this is undeniable and sonics are spectacular but this is more a Beethoven for in the showroom than for a regular ride. Wilhelm Furtwängler - Wiener Philharmoniker / Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra / Orchester der Bayreuther Festspiele (studio & live 1950-1954): Furtwängler fares better live than in the studio but this readings (all studio except for the 2nd, 8th and the 9th) make a strong case for Furt's unmatched narrative powers. However timid by times, especially when one compares it with Furtwängler's wartime recordings, this is a cycle that never fails to make an impact. Like with his 1954 Walküre these are recordings that, despite my initial reservations (mainly about slow tempi), are well worth coming back to . Stanisław Skrowaczewski - Saarbrücken Radio Symphony Orchestra (studio 2005-2006): From a box of recordings that contains as much as complete symphony cycles of Bruckner, Brahms and Schumann comes the next Beethoven cycle of this list. The Bruckner of Stanisław Skrowaczewski is legendary, it was a calling card that made me curious towards other recordings of the Polish-American conductor-composer, and it is almost inevitable that it's with Bruckerian eyes that I look at this Beethoven. The characteristics of Skrowaczewski's Bruckner approach seem indeed to shine through in his Beethoven. (Or perhaps I better say that his approach makes Beethoven and Bruckner brothers, be it from different eras.) This is Beethoven with the knowledge of Bruckner coming behind him. Despite its romantism Skrowaczewski's Beethoven doesn't suffer from sentimentality. Its tempi are swift (for instance the opening movement of the 5th is faster than Carlos Kleiber on his famous recording for DG and on par with Frans Bruggen's performance on period instruments, in the opening of the Eroica he is almost 3.5 minutes faster than Thielemann). Not that timings matter much because more important is the fact that the tempi feel completely natural. As always with Skrowaczewski they feel right. In a conducting style that's free of mannerism, it does fully justice to the Wagnerian idea of the orchestra as an entity that has to be capable of depicting everything that is in nature. Skrowaczewski has an ear for detail that reflects years of dedication and a full understanding of the role every single instrument has in that organic machine. With that rare quality to bring out opposites together in a non-conflicting way, Skrow's Beethoven is weighty yet light, purposeful yet free, sharp with soft edges and dark yet colorful. Flying on strings of desire because, as with his Bruckner (and his approach in general), for Skrowaczewski the strings are the beating heart of the orchestra. In this respect you can call him the anti-Solti ("concentrate on the brass and woodwinds and leave the strings to it"). It results in a cycle, lushful in sound, that's ranked at the top of my list of modern Beethoven cycle recordings. Riccardo Chailly - Gewandhausorchester (Gewandhaus zu Leipzig 2007-2009): For endeavours in high tech sound one can always rely on the recorded output of Riccardo Chailly. Chailly's Beethoven cycle is one - it won't come as a surprise to anyone who knows his Mahler and Bruckner cycles - in glorious HiFi. In his reading Chailly takes note of Beethoven's metronome markings, to the border of sounding obsessed by them. This is Beethoven, swift and by times rushed, that led his head speak more than his heart. A Beethoven that does want to prove something - he works his way up into a world in which daddy Haydn serves both as a source of inspiration and as a reason for revolt - but here the composer (a full-blooded romantic according to E.T.A. Hoffmann) keeps himself when it comes to making firm statements down to earth. This is, despite the historically informed tempi, very much Chailly’s Beethoven. He derives the gorges of the human soul not from the penetrating insights of life itself but from the novelle that is in the suitcase for a holiday in the sun. He flashes you by, risking a speed ticket, with a beautiful woman in the passenger seat. Here, the heart's passions do not lead to worldly insights, but are translated into making the blitz in front of crowded terraces where he drives by in a whisper, inadvertently emphasising that for that carefully served moment of nochalante charm, he stood in front of the mirror all morning. This Beethoven is, it will be clear, not pregnant with profound expression. In these recordings Chailly once again testifies to the consciousness of the modern conductor (note: everyone after Karajan is modern) who considers the living room just as much, if not more, as his stage than the concert hall. Just like his symphony cycles of Mahler and Bruckner, Chailly's Beethoven swims around in a benevolent bath of sound. But what works so well in Mahler - the unfolding of a broad tapestry of timbres – works a lot less with Ludwig: indulging in sonority. An over-sanitized approach puts Beethoven behind the window of the showroom. Here, the gloss of the blister packaging hides the view on the narrative. The storm in the Pastorale is rather a special effect from the Disney studios, we look at it in wonder and admiration but feel no need to take shelter: instead of being in earthly nature we are on a holodeck of the Starship Enterprise. The first two symphonies benefit the most from this approach. Arriving at the third, the groundbreaking Eroica, Chailly’s obsession for Beethoven’s metromone markings deprives us of an all too profound view on the revolutionary character of the piece. Bathed in the delights of modern stereo and the for this occasion somewhat too smooth working machine that is the Leipzig Gewandhausorchester – the musical delivery could have cracked more, could have taken a bit more of a breath and could have added more gravity to the lyrical lines - the drifts of Beethoven are to a good extent lost in favour of making good grace. The 2nd and a voracious 9th (that clocks in at just 62 minutes!) are my (current) favorites of a cycle in which Chailly gives us a historically informed Beethoven with a modern orchestra. A cycle for which a lot can be said but I will not trade the mono-Schuricht for this venture in crisp & clear stereo. - Wouter de Moor

2 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed