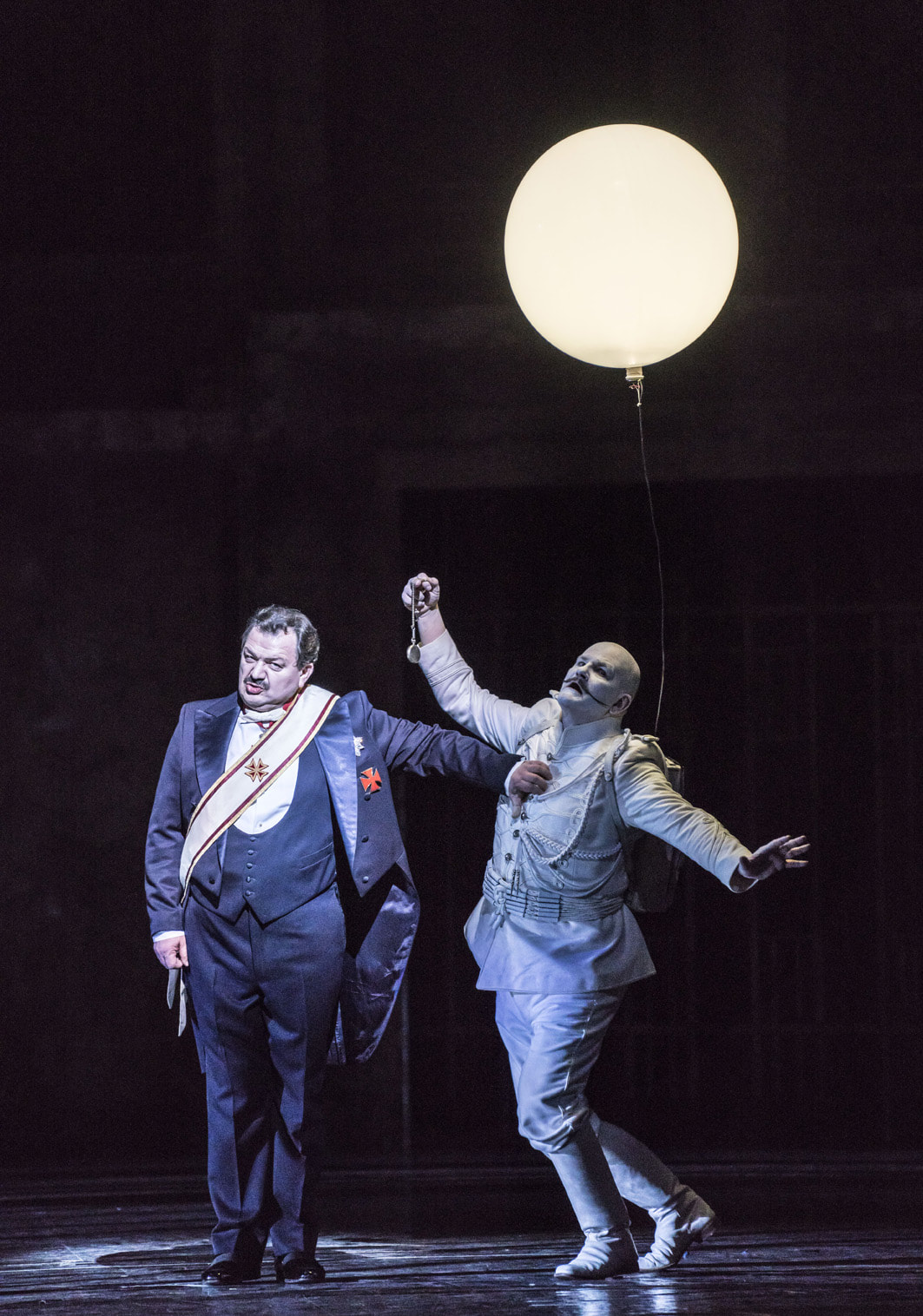

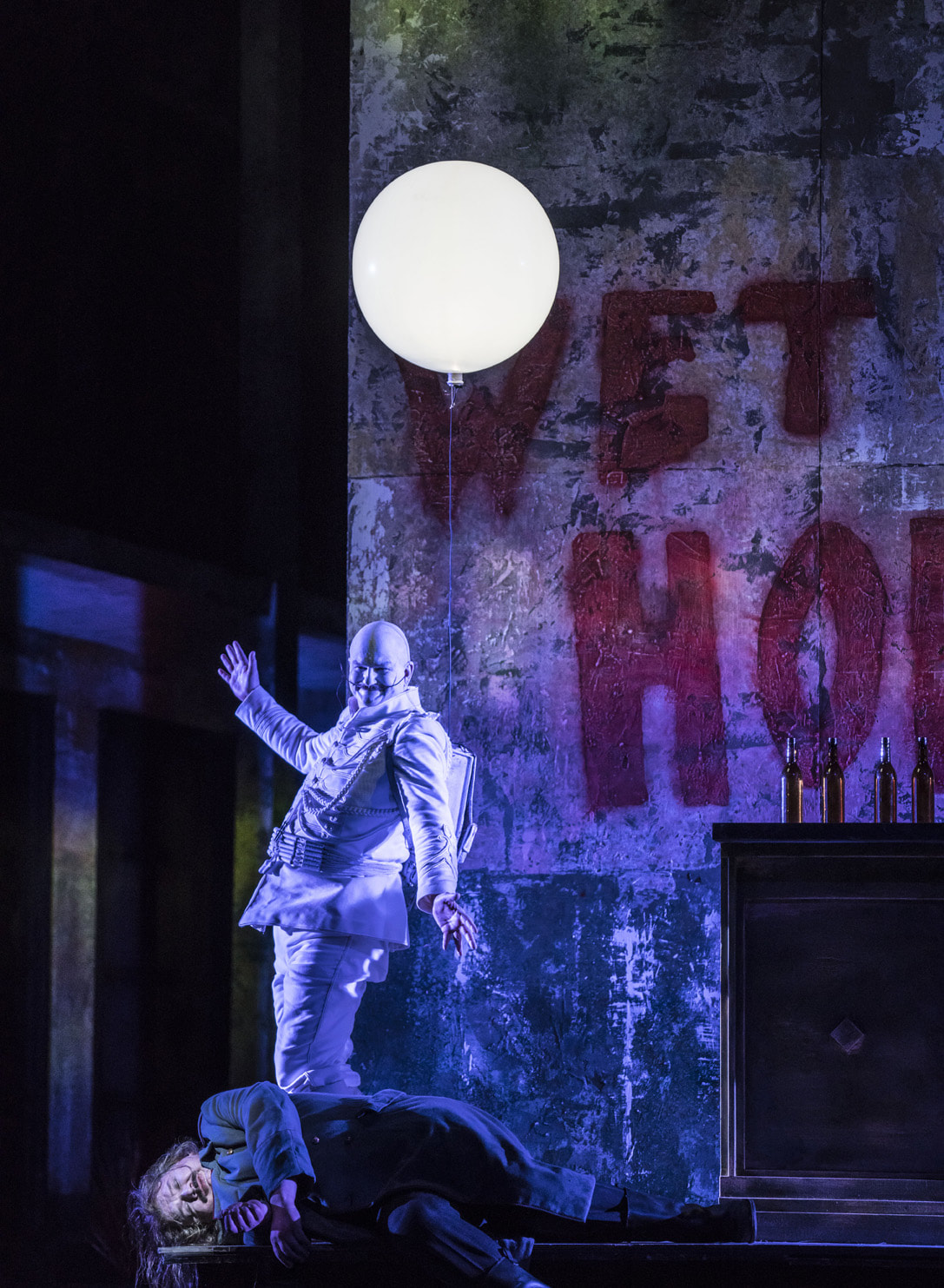

In 2014, the Dutch National Opera was the first to present a fully-staged version of Arnold Schönberg's mega-cantata. This season, that production returns. As early as 1927, serious thought was given to a fully-staged production of Arnold Schönberg's Gurre-lieder, but it was not until 2014, at express wishes of conductor Marc Albrecht and under the direction of Pierre Audi, that this idea really materialized. Once started as a song cycle for soprano, tenor and piano (an entry for a competition of the Vienna Tonkünstler-Vereins), the composition would burst out of every conceivable musical joint by the time it was completed in 1911. At the premiere in 1913, under the baton of Franz Schreker, 757 musicians took part (thereby almost reducing Gustav Mahler's 8th symphony - in which more than 400 musicians took part at its premiere in 1910 - to a piece of chamber music). That enormous number of the first performance is not reached in this production of The Dutch National Opera, only 235 musicians populate the stage and orchestral pit, but the use of musical means is still far above average when compared to other pieces in the Late-Romantic repertoire. In the story of Gurre-Lieder - based on a poem by Danish writer Jens Peter Jacobsen (1847-1885), who in turn drew inspiration from the story of King Waldemar Atterdag (1320-1375) - Waldemar is having a love affair with Tove. An affair to which Waldemar's wife Helvig do not react too subtly: she gets Tove killed, after which Waldemar fell into insanity. Schönberg captures all of this in opulent music in which he deliberately pushes more than a few boundaries. Gurre-Lieder was a point of arrival for Schönberg, the conclusion of an era, not only for himself but also for the history of music up to that point. From now on everything had to change. When the orchestration of Gurre-Lieder was completed in 1911, he had already gone on the atonal path with Erwartung in 1909, and after Gurre-Lieder, the man who wanted to emancipate the dissonant no longer wished to look back. (That his music after that was considered merely atonal Schönberg contested. His music might have come about according to other musical principles, but it still contained tones. According to him, the fact that the dissonants were experienced as ugly was mostly a matter of conditioning - by upgrading the dissonance to something with which beauty could be expressed in addition to ugliness and conflict, the musical vocabulary could be considerably expanded.) Gurre-Lieder does not suffer too much from dissonants. Their presence is amply counterbalanced by pleasant, at times coquettish, harmonies. Music in which Waldemar and Tove share their ecstasy and their fear of loss. As it befits a good Late-Romantic work, in Gurre-Lieder we also find a pre-occupation with death. The fear of the end, before the end is even there. Finiteness that can only be overcome with love. The end comes, for Tove and also for Waldemar, who after the message of the Waldtaube about Tove's death, must be considered lost for this world. They find each other again, the king and his beloved, in nature, transfigured in love, transcending death. A gathering that we find, more than on stage and in the sounds that rise from the orchestra pit, back in the score, because in Gurre-Lieder the music is quite dense. Pleasant, sensual tones together with musical saccharides are transformed into a tapestry of sound in which many who are enchanted by it still regret that the composer, Schönberg, would devote himself after the completion of this super oratorio mainly to atonal music. Not by me because Gurre-Lieder is at its most interesting in the moments when Schönberg grants the listener a glimpse into the future. When he, rather than dwelling in Romantic loftiness, looks forward to the music that will come after Gurre-Lieder, the dodecaphony, and refers to cabaret. The Sprechgesang van Der Sprecher and the cabaratesque character of Klaus Narr are both highlight and delight. Here Schönberg explicitly seeks the contrast with the (all too) Romantic density of the piece – it lets the audience some air and gives Gurre-Lieder more texture. The massive orchestration (I will think of it the next time I see someone questioning the orchestration of the symphonies of Robert Schumann for being too dense) gave the impression that what works, for example, well in Tristan und Isolde, an approach that emphasizes the passion that speaks from the score, has the opposite effect in the case of Gurre-Lieder. The idea surfaced (and never left) that Marc Albrecht could have suffice with a lighter and more transparent approach - whether or not accompanied by a further reduction of the orchestra - because the singers were hardly able to cope with the sonic violence to which they were subjected by orchestra and conductor. For this production of Gurre-Lieder, the piece has been adapted on a few points. The play begins with a poem by Jacobsen, recited by the Sprecher, who normally appears only in the third part, while Klaus Narr, who normally also only appears in the third part, shows up next to Waldemar right from the start. It are interventions that glue together on stage what has been cut by the different songs and orchestral interludes. It inadvertently sheds light on the lack of a strong narrative and makes clear what Gurre-Lieder is not: an opera or a music drama. Even in this production, in which designer Christof Hetzer depicts decay in a beautiful and atmospheric way - in an environment where you can imagine Götterdämmerung or Elektra - the operatesque Gurre-Lieder remain a mega-cantata with beautiful pictures. Rather a piece with compelling moments than a compelling piece. It wasn’t meant to be, also after a second visit. The hope that Schönberg's Late Romantic super cantata would grab me turned out to be largely in vain. Again, the piece did not seem to me the opera that Marc Albrecht and Pierre Audi apparently see in it. The coin, when it comes to Schönberg's Late-Romantic compositions (with the inevitable Verklärte Nacht as its most famous example), has not yet dropped. This is, in Gurre-Lieder's case, partly due to the sumptuous orchestration in which Schönberg refers to Wagner and Richard Strauss but remains miles away from them in terms of expressiveness. I could appreciate it better now than four years ago when Gurre-Lieder didn't speak to me at all. Then the supposingly next-step-after-Wagner turned out to be a seven mile step backwards - both musically and dramatically. But I had a better time this time, I managed to cope better with what is clearly an important piece in the musical canon. It was not the composers Schönberg himself refered to but the composers who were (partly) inspired by his Late-Romantic compositions (Korngold, Schreker) who made Gurre-Lieder's music more comprehensible for me. A declaration of love, however, will have to wait. The Lied der Waldtaube is insanely beautiful (for the version of Jard van Nes with the Schönberg Ensemble you can wake me up at night), but the choral singing keeps puzzling, or better baffling, me – here Schönberg doesn't exactly present himself as the prodigal son of Georg Friedrich Händel to put it mildly. Waldemar Attevar was the historical character that formed the basis of the Waldemar of Gurre-Lieder. Attevar is Danish for "another day" and with the beginning of a new day Gurre-Lieder closes. A choir sings about the rise of the sun (Seht die Sonne) and it becomes clear how fed up Schönberg must have been with tonality. He must have meant this closing as a cynical joke. More than the (obvious) musical references of Gustav Mahler (Auferstehung) and Richard Strauss (who shows us with the intro of Also Sprach Zarathustra the true grandeur of a C major chord) I have to think of a Dutch stand-up comedian: Hans Teeuwen. He once concluded one of his shows with an epic poem that turned out to be a big joke - it was just a mash-up of clichés. He resolutely expelled the audience that had rewarded him with an ovation - refusing to receive their final applause. I couldn’t help thinking of Schönberg's refusal to receive the applause after Gurre-Lieder's successful premiere where he firmly kept his back turned to the audience. A few years earlier ( in 1908) the public at large had rejected the fresh air from other planets from his second string quartet ('Ich fühle luft von anderem planeten'), now they rewarded the stench of the overblown power chords with which he had set a closing bar behind music history with a standing ovation. He didn't want and couldn't hide his chagrin about that. By times, Gurre-Lieder took my breath away – be it not always for recommended reasons. Once home, the breath of fresh air, coming from the second string quartet, was more than welcome. The Dutch National Opera Dates 18 April - 5 May 2018 Conductor: Marc Albrecht Nederlands Philharmonisch Orkest Koor van De Nationale Opera Kammerchor des ChorForum Essen Director: Pierre Audi Stage and costumes: Christof Hetzer Waldemar: Burkhard Fritz Tove: Catherine Naglestad Waldtaube: Anna Larsson Bauer: Markus Marquardt Klaus Narr: Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke Sprecher: Sunnyi Melles - Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed