Parsifal in Bayreuth: The Augmented Reality of a visit to the opera

This year's Bayreuther Festspiele had a novelty. For the first time in the history of the Festival, an opera production here was implemented with Augmented Reality.

A few years ago, there was a dino app on my phone. With that app you could conjure up a dinosaur in your living room wherever you pointed your camera. See a diplodocus walking back and forth across the couch. Or see a Pterodactyl skim past the ceiling light. Cinematic fantasy images that complemented an everyday reality. Fun for a while (and for your 10-year-old nephew) but after the initial wow effect, you (and your 10-year-old nephew) quickly grew tired of it.

It often takes a while for new techniques, after the initial amazement about them has subsided, to prove their added value. Augmented Reality now has a wide range of applications. You can use it to virtually furnish a room, see which furniture you think fits best. In the workplace, you can use it to introduce employees to new techniques and you can use augmented reality to clarify traffic situations and make buildings from a (distant) past rise up on the spot.

So it was only a matter of time before Augmented Reality would pop up in the theater as well. The Bayreuther Festspiele, the Wagner festival that likes to present modern, avant-garde productions, had a novelty this year. For the first time in the history of the Festival, there was some wrangling over its desirability and feasibility, an opera production here was given an Augmented Reality shell. The director who introduced this novelty was Jay Scheib. A theatermaker who likes to lard his productions with new media.

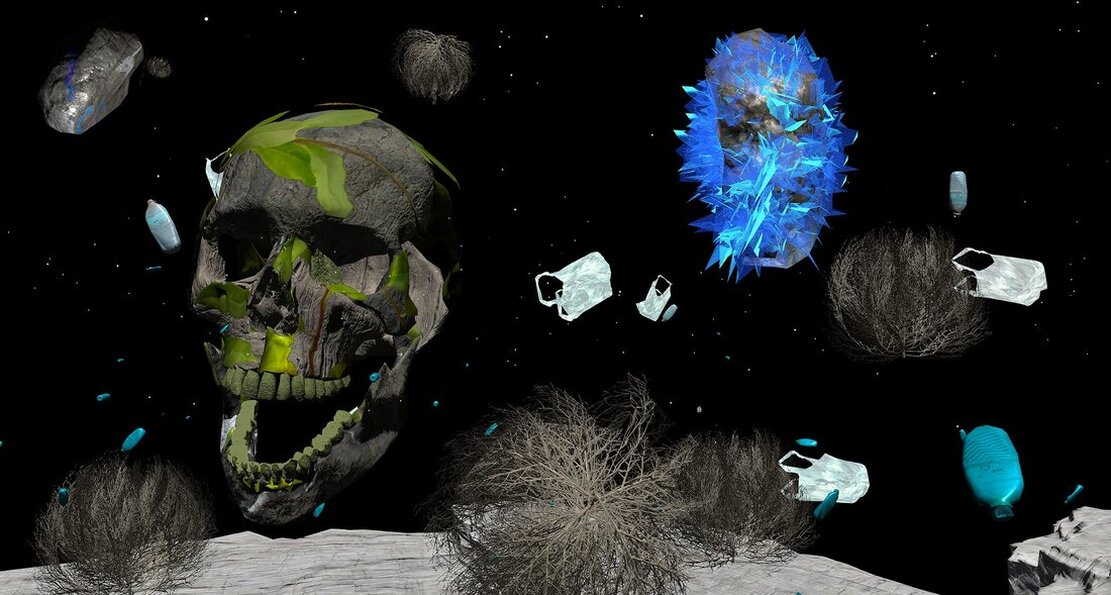

The AR portion did require special AR glasses. These were available to part of the audience; the glasses were so pricey that they were only available to 200 of the nearly 2000 visitors. How essential those AR images were for properly assessing the production I can only distill from what I have read about them. Not very essential, I deduce. All sorts of things move on and off stage. The result, something apparently resembling a video game from 10 years ago, does not necessarily stoke curiosity.

It often takes a while for new techniques, after the initial amazement about them has subsided, to prove their added value. Augmented Reality now has a wide range of applications. You can use it to virtually furnish a room, see which furniture you think fits best. In the workplace, you can use it to introduce employees to new techniques and you can use augmented reality to clarify traffic situations and make buildings from a (distant) past rise up on the spot.

So it was only a matter of time before Augmented Reality would pop up in the theater as well. The Bayreuther Festspiele, the Wagner festival that likes to present modern, avant-garde productions, had a novelty this year. For the first time in the history of the Festival, there was some wrangling over its desirability and feasibility, an opera production here was given an Augmented Reality shell. The director who introduced this novelty was Jay Scheib. A theatermaker who likes to lard his productions with new media.

The AR portion did require special AR glasses. These were available to part of the audience; the glasses were so pricey that they were only available to 200 of the nearly 2000 visitors. How essential those AR images were for properly assessing the production I can only distill from what I have read about them. Not very essential, I deduce. All sorts of things move on and off stage. The result, something apparently resembling a video game from 10 years ago, does not necessarily stoke curiosity.

Now Parsifal is difficult to stage anyway. It is an opera with little to no action. It is an opera that, more than any other opera in the repertoire, raises the problem for singers/actors/directors of how to deal with the time the music leaves them. Apathy in the Personenregie plagues many a production of Wagner's last opera, ein Bühnenweihfestspiel, and that defect also manifests itself emphatically in Schreib's production. Schreib does make an effort to emphasize the action in the story. The spear that Klingsor throws at Parsifal in the second act comes right at you. It elicited a brief oh-reaction from the AR glasses-wearing part of the audience. It's similar to the first 3D films where all sorts of things are thrown at the audience. As if to emphasize novelty, not so much to tell or support a story. Klingsor's spear may be illustrative of a production in which technical gadgets are supposed to disguise the fact that the production lacks good, insightful ideas.

Wagner's music dramas can be enjoyed on several levels. From the first acquaintance, that acquaintance in which you, even without knowledge of the libretto, discern a story, a drama, in the music. To the ever new layers you tap into as you delve deeper into the story and its background. For this production of Parsifal, Scheib does not seem to have gone much further than tapping into that first layer, the introduction to Wagner's wonderful musical world to which, at least in the AR section, he has sought flashy images. If his purely visual approach conceals substantial ideas about Parsifal and/or Wagner, they seem, for the time being, to be hidden from view.

Wagner's music dramas can be enjoyed on several levels. From the first acquaintance, that acquaintance in which you, even without knowledge of the libretto, discern a story, a drama, in the music. To the ever new layers you tap into as you delve deeper into the story and its background. For this production of Parsifal, Scheib does not seem to have gone much further than tapping into that first layer, the introduction to Wagner's wonderful musical world to which, at least in the AR section, he has sought flashy images. If his purely visual approach conceals substantial ideas about Parsifal and/or Wagner, they seem, for the time being, to be hidden from view.

Jay Scheib's website features an AR impression of Siegfried and the Dragon. Fafner pulls from the back rows of the Festspielhaus to the stage where Siegfried is waiting for him. Meanwhile burning down chairs (and audience) with his fire-breathing mouth.

It seems indicative of Schreib's approach, he seeks spectacle to a story rather than an interpretation of themes and motifs underpinning that story. Perhaps Scheib's approach would have done better in the Ring operas with its fantasy elements.

It seems indicative of Schreib's approach, he seeks spectacle to a story rather than an interpretation of themes and motifs underpinning that story. Perhaps Scheib's approach would have done better in the Ring operas with its fantasy elements.

To be clear. Attending Parsifal at the Festspielhaus remains a special event regardless. And yours truly saw any lack of AR in an otherwise flat production more than compensated by the augmented reality that a visit to Wagner's opera house already is. Moreover, he could rejoice in the augmented audio of the Festspielhaus through the seating, in the front rows near the stage, where the singers are in front of you and you are basically sitting on top of the orchestra. There it could be observed that singers, orchestra and chorus performed exceptionally well. Georg Zeppenfeld is something of a jack-of-all-trades in Bayreuth. He is taking on several roles in Bayreuth this year, as usual by now. In addition to the role of Gurnemanz, he is performing King Marke (Tristan und Isolde), Daland (Fliegende Hollander) and Hunding (Die Walkure). His Gurnemanz is an authority, his bass voice carrying the role in a completely natural and organic way. His stage presence is not the most succinct but he casts himself in an otherwise flat persona as a convincing Gurnemanz - the somewhat mysterious hermit and narrator who carries the story. For the role of Kundry, it was Ekaterina Gubanova's turn in this performance (she alternates the role with Elīna Garanča). The Personenregie gives her little of substance to deal with but Gubanova's voice and stage presence are enough here to give Kundry imposing form. There is a kind of shadow version of Kundry walking around in this production. A flower girl (?) who at times imitates Kundry in her acting and in the overture makes love to Gurnemanz. Gurnemanz, in that overture, seems to realize in time how Amfortas got wounded and withdraws from her. At the end of the opera, when Parsifal unites (seems to unite) with Kundry, the shadow-Kundry rejoins Gurnemanz. A kind of All you need is love-ending. Shadow-Kundry shows that Gurnemanz apparently didn't always take the celibate oath of the grail knights very seriously; what else her role is supposed to represent exactly I don't know, she is illustrative of the forgiving approach that Kundry is generally granted in modern stagings. (I have yet to see the first production in which Kundry, in accordance with libretto, dies. Tcherniakov's production in which Kundry is killed at the end by Gurnemanz may be called an exception in that regard).

The stage images Scheib chooses are quite conventional. They occasionally invite speculation. (Is the monolith in the first act referring to 2001: A Space Odyssey? An artifact, otherworldly in origin, that jumpstarted the evolution of human consciousness, the creation of a civilization?) The castle of Klingsor (an evil wizard in stiletto heels, a fantastic role by Jordan Shanahan) has a door, an opening in the shape of the grail revealed in the first act, which in turn resembles a vulva. The flower garden in which the magician has his flower girls seduce grail knights is a frenzied landscape decorated in kaleidoscopic colours (also without AR). The temptation to sex, to sin, is apparently not enough here (consider also the sex Gurnemanz had with shadow-Kundry - seemingly without fatal consequences). There are corpses of grail knights, decapitated, mutilated, in the garden. Carressed by the flower girls. As if what happened to the knights happened beyonf their control and they themselves cannot help being mere instruments in the hands of an evil sorcerer - the actual perpetrator of these crimes. In the third act, the world has turned into a desolate, post-apocalyptic landscape where Gurnemanz apparently lives in a mining machine. He has walked around with it for a few decades but now, in the third act, Parsifal finally thinks it is time to take the spear back to where it came from, the grail community. To Amfortas with his unstoppable wound. To the world that has waited so long for redemption. The redemption of the saviour (who also redeems himself) here comes with the smashing of the holy grail. A literal break with the past that should be liberating and bring hope for the future. Whether that hope will prove to be vain or not we do not find out. The staging is ambiguous in this (the dove at the end is only visible with AR glasses) and in Wagner's notes ambiguity always lurks.

Andreas Schager replaced the ailing Joseph Calleja in the role of Parsifal at a rather late stage. His voice is (still) impressive and unwavering, although (by now) it is more like that of a Tristan than that of a (young) Parsifal in terms of power. Derek Welton, who has previously performed Klingsor several times in Bayreuth, made Amfortas' agonies palpable with an authoritative, rich and robust voice. Pablo Heras-Casado made his debut as a conductor in Bayreuth, using fairly swift tempi. He finished the job in roughly 4 hours (right within time, Hartmut Haenchen would say - Ha!). No complaints from me about that, although some moments could have been articulated a bit more. Also, on the audio front, I noticed that the bells during the Transformation scenes in the first and third acts did sound very timid. It may be Bayreuth's real-life bells, tirelessly chiming long sessions every day, had somewhat tarnished my perception of them.

When Adolphe Appia saw Parsifal at its premiere in Bayreuth in 1882, he envisaged for Parsifal and other Wagner productions a future leading role for the then new technology of electric light. Appias ideas, which would find their realisation in Wieland Wagner's productions after World War II, led the Wagner productions of the late 19th century away from figurative sets with all their embellishments. Those would only distract from what the stage should really be about: showing the singers/actors as part of the total whole of the Wagner drama in which the music was the determining factor. One could argue that this AR-Parsifal takes a reverse path. The Augmented Reality (and again I infer this from what I have read about it) causes overstimulation and it obscures the view on the singers (as if looking at a stage through a screensaver). It thus fits into a time with its profusion of stimuli, a time in which we seem to have completely lost the distinction between main and secondary issues at times, but for the time being AR images are no more a 21st-century incarnation of 19th-century painted sets than they claim the same revolutionary role as the stage lighting in which Appia, in the late 19th century, saw an indispensable technique to renew opera productions (and Wagner's in particular).

A day later it was the turn of Tannhäuser in a production by Tobias Kratzer and the difference with Parsifal could not have been bigger. This production is proof that using (relatively) new media (like video) and bringing together pop culture and classical repertoire can be done completely naturally with stunning results. It was a textbook example that ideas carry a production, not technology.

A day later it was the turn of Tannhäuser in a production by Tobias Kratzer and the difference with Parsifal could not have been bigger. This production is proof that using (relatively) new media (like video) and bringing together pop culture and classical repertoire can be done completely naturally with stunning results. It was a textbook example that ideas carry a production, not technology.

PARSIFAL, Bayreuther Festspiele, 15 August 2023

Amfortas - Derek Welton

Titurel - Tobias Kehrer

Gurnemanz - Georg Zeppenfeld

Parsifal - Andreas Schager

Klingsor - Jordan Shanahan

Kundry - Ekaterina Gubanova

Jay Scheib (director)

Mimi Lien (designs)

Meentje Nielsen (costumes)

Rainer Casper (lighting)

Joshua Higgason (AR and video)

Marlene Schleicher (dramaturgy)

Bayreuth Festival Chorus (chorus director: Eberhard Friedrich)

Bayreuth Festival Orchestra

Pablo Heras-Casado (conductor)

Amfortas - Derek Welton

Titurel - Tobias Kehrer

Gurnemanz - Georg Zeppenfeld

Parsifal - Andreas Schager

Klingsor - Jordan Shanahan

Kundry - Ekaterina Gubanova

Jay Scheib (director)

Mimi Lien (designs)

Meentje Nielsen (costumes)

Rainer Casper (lighting)

Joshua Higgason (AR and video)

Marlene Schleicher (dramaturgy)

Bayreuth Festival Chorus (chorus director: Eberhard Friedrich)

Bayreuth Festival Orchestra

Pablo Heras-Casado (conductor)

- Wouter de Moor