The road to Bayreuth (2017)

A Meistersinger for starters

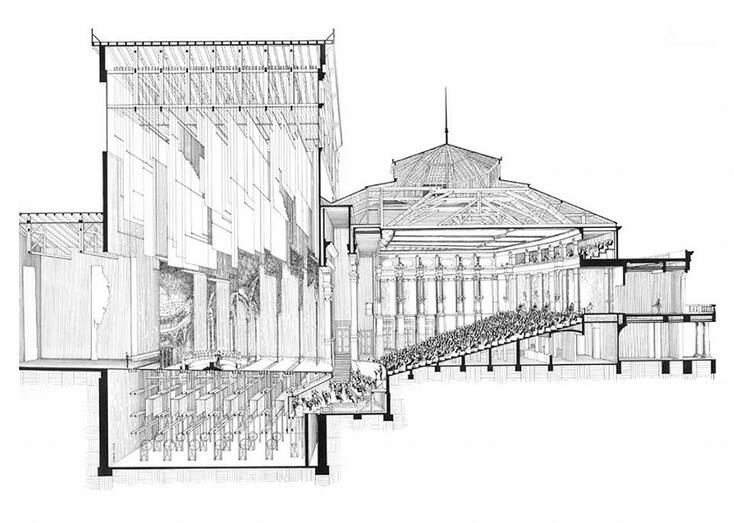

It was like a dream come true. The premiere of Der Ring des Nibelungen in 1876 at the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth. A dream that confronted Richard Wagner with the shortcomings of the theater techniques of his time. For a short time, so it seemed, he wished, except for an invisible orchestra also for an invisible stage. Dissatisfied as he was with what he saw there. The composer, who found solutions for many musical problems and challenges, failed to find the key for a satisfactory staging for his music dramas. The visual part of the Wagner theater was a puzzle that remained unresolved in Wagner's life. And more than 140 years later, the staging of a Wagner opera still puzzles directors; aesthetically, dramatically and morally. Especially in Bayreuth the past still weights heavily on the shoulders of those who stage an opera from Wagner. Bringing Wagner to the stage means taking the controversial past of Bayreuth into account, the time the place was affiliated with the Nazi-regime, the time uncle Wolf paid the Festspiele a visit. The need for a departure from a Teutonic calling for arms results in provoking and challenging productions.

To visit a complete Ring cycle in Bayreuth was on my bucket list for a while and this year it finally came to fruition. More about the Ring later. Arriving in my hotel on August 7 a surprise awaited me there. It was bad news for the woman involved – she had a headache and offered her ticket for Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg for sale – but I was able to go to the opera one day earlier than initially planned.

A few years ago, Barry Kosky (intendant of the Komische Oper Berlin) was asked by Katharina Wagner (great granddaughter of the composer and head of the Festspiele) to direct Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Kosky initially did not like the idea. He saw Meistersinger as a typical German piece, an inheritance of German culture, to which he had nothing to add. Besides that, he hated Wagner.

Kosky, however, came along, delved deep into the piece and began to love Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Nürnberg was Wagner's ideal image of a society. A fairytale world of craftsmen and artists (Hans Sachs is both cobbler and master singer). Wagner saw Nürnberg as the heart and soul of Germany. An image, not rooted in reality, because , in fact, Nürnberg was the city of the banking system, where its most famous son, Albrecht Dürer, learned everything he needed to know in Italy. In his staging, Kosky combines elements of Wagner's personal life with the history of Nürnberg. He turns Nürnberg into Villa Wahnfried; Wagner's ideal home in Bayreuth. A place where Wagner himself plays Hans Sachs while Cosima has been assigned the role of Eva. At the end of the first act, Wahnfried changes into the courtroom where, after the Second World War, the Nürnberger processes took place (a spectacular change of scenery with open curtain).

Barry Kosky is a Jewish theater maker and the fact that he is Jewish should not be brought into attention. It is, however, in relation to Der Meistersinger almost inevitable. Newsreels are not tired to note that Barry Kosky is the first non-German and Jewish director in Bayreuth who is to direct Die Meistersinger. More than any other Wagner opera it has been ideologically abused by the Nazis. It's a piece in which Wagner's aversion to the Jews, the Italians & French, and music critics (Eduard Hanslick) are brought together, like some kind of Frankenstein, in the character of Sixtus Beckmesser. Beckmesser is a Meistersinger and, unlike what that title suggests, a dabbler. When he sings his Meisterlied, he sounds terrible (the out of tune harp that accompanies him doesn't help either). For the Nazis, Beckmesser was Judd Süß. Die Ewige Jude caught in an opera. Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg was a favorite of Adolf H. A nostalgic trip to a past that has never been, a wet-dream about the ideological purity of Germany. What to do with this opera, with the character Beckmesser, after World War II? The easiest thing would be to forget it, if only that music …. if only it would suck.

A few years ago, Barry Kosky (intendant of the Komische Oper Berlin) was asked by Katharina Wagner (great granddaughter of the composer and head of the Festspiele) to direct Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Kosky initially did not like the idea. He saw Meistersinger as a typical German piece, an inheritance of German culture, to which he had nothing to add. Besides that, he hated Wagner.

Kosky, however, came along, delved deep into the piece and began to love Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Nürnberg was Wagner's ideal image of a society. A fairytale world of craftsmen and artists (Hans Sachs is both cobbler and master singer). Wagner saw Nürnberg as the heart and soul of Germany. An image, not rooted in reality, because , in fact, Nürnberg was the city of the banking system, where its most famous son, Albrecht Dürer, learned everything he needed to know in Italy. In his staging, Kosky combines elements of Wagner's personal life with the history of Nürnberg. He turns Nürnberg into Villa Wahnfried; Wagner's ideal home in Bayreuth. A place where Wagner himself plays Hans Sachs while Cosima has been assigned the role of Eva. At the end of the first act, Wahnfried changes into the courtroom where, after the Second World War, the Nürnberger processes took place (a spectacular change of scenery with open curtain).

Barry Kosky is a Jewish theater maker and the fact that he is Jewish should not be brought into attention. It is, however, in relation to Der Meistersinger almost inevitable. Newsreels are not tired to note that Barry Kosky is the first non-German and Jewish director in Bayreuth who is to direct Die Meistersinger. More than any other Wagner opera it has been ideologically abused by the Nazis. It's a piece in which Wagner's aversion to the Jews, the Italians & French, and music critics (Eduard Hanslick) are brought together, like some kind of Frankenstein, in the character of Sixtus Beckmesser. Beckmesser is a Meistersinger and, unlike what that title suggests, a dabbler. When he sings his Meisterlied, he sounds terrible (the out of tune harp that accompanies him doesn't help either). For the Nazis, Beckmesser was Judd Süß. Die Ewige Jude caught in an opera. Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg was a favorite of Adolf H. A nostalgic trip to a past that has never been, a wet-dream about the ideological purity of Germany. What to do with this opera, with the character Beckmesser, after World War II? The easiest thing would be to forget it, if only that music …. if only it would suck.

Die Meistersinger is an opera of breathtaking beautiful moments. The way Wagner leads his infinite melody through the dialogue, the magical chorus, Hans Sachs' Wahn monologue (in which Wagner refers to Tristan & Isolde) and the unsurpassed quintet (play that on my funeral) make Die Meistersinger a piece of art that is impossible to resist. It may be as well the selfishness of the listener who does not want to be without Wagner (like the reader who doesn't want to leave Céline alone despite his virulent anti-semitism) as well as its musical significance that kept the opera on the repertoire all those years.

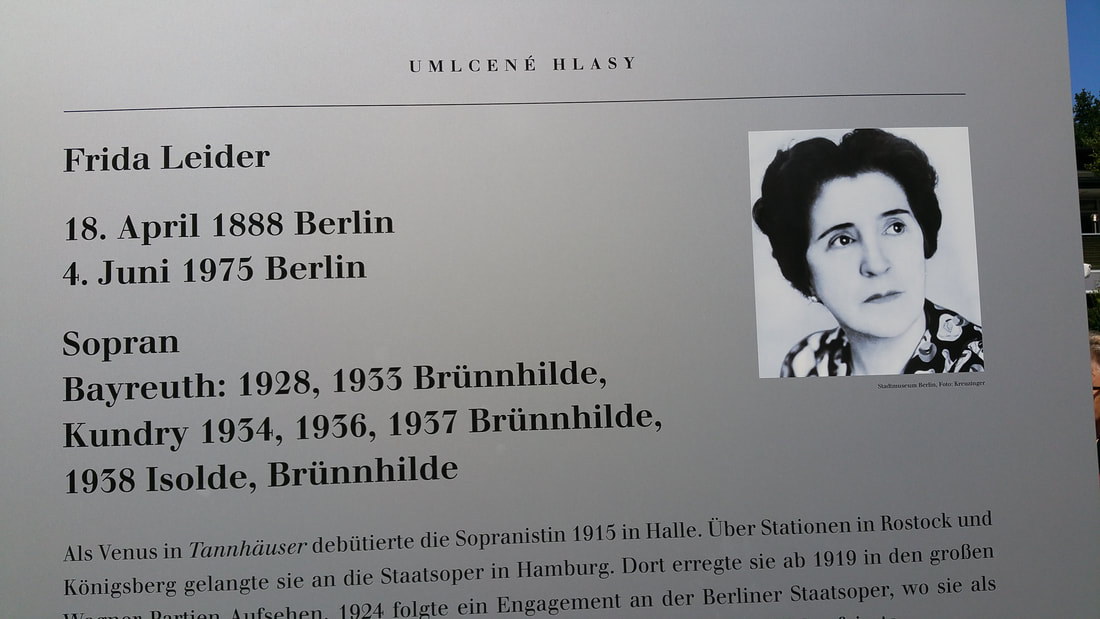

Whether Beckmesser is really an anti-semitic caricature is a subject on which more pages of text are spent than there are drops in the ocean. Kosky thinks that Beckmesser has undeniably 19th century anti-semitic characteristics and plays with that. In doing so he delivers a few scenes that causes some unease. For instance at the end of the second act where Hans Sachs (dressed as Richard Wagner) puts Beckmesser on trail. It materializes into a scene that's perhaps best described as the strange case for German humor. (It can count on some acclaim from the audience. I had to think about the German book of humor and the small size of it) While the public laughs at the humiliation of Beckmesser (Sachs/Wagner actually tells him that he does not belong in Nürnberg) a balloon inflates, showing the face of a caricature Jew, wearing a yarmulke with the star of David. It is a moment of uneasiness. You can feel the inconvenience in the audience. The clench between Sachs and Beckmesser is stripped of its humor. Those who have laughed are faced with the true nature of the foregoing; laughing at anti-semitism while the Jewish caricature reminds us of the evil consequences of that anti-semitism. It causes some discussion afterwards. Good. It is at times like these that the staging that goes on in the Festspielhaus continues outside. Outside is a memorial “Verstummte Stimmen”, plaques set up like in a cemetery, for those Jewish musicians and singers who worked in the Festspielhaus and, because of them being jewish, got into trouble in Bayreuth (and/or Nazi-Germany).

Whether Beckmesser is really an anti-semitic caricature is a subject on which more pages of text are spent than there are drops in the ocean. Kosky thinks that Beckmesser has undeniably 19th century anti-semitic characteristics and plays with that. In doing so he delivers a few scenes that causes some unease. For instance at the end of the second act where Hans Sachs (dressed as Richard Wagner) puts Beckmesser on trail. It materializes into a scene that's perhaps best described as the strange case for German humor. (It can count on some acclaim from the audience. I had to think about the German book of humor and the small size of it) While the public laughs at the humiliation of Beckmesser (Sachs/Wagner actually tells him that he does not belong in Nürnberg) a balloon inflates, showing the face of a caricature Jew, wearing a yarmulke with the star of David. It is a moment of uneasiness. You can feel the inconvenience in the audience. The clench between Sachs and Beckmesser is stripped of its humor. Those who have laughed are faced with the true nature of the foregoing; laughing at anti-semitism while the Jewish caricature reminds us of the evil consequences of that anti-semitism. It causes some discussion afterwards. Good. It is at times like these that the staging that goes on in the Festspielhaus continues outside. Outside is a memorial “Verstummte Stimmen”, plaques set up like in a cemetery, for those Jewish musicians and singers who worked in the Festspielhaus and, because of them being jewish, got into trouble in Bayreuth (and/or Nazi-Germany).

As an audio-only document, Die Meistersinger is in a league of its own (the recording under the baton from Rafael Kubelik with Gundula Janowitz as Eva is in my suitcase for the so-called desert island). In the top of the Festspielhaus, in Der Galerie, at 40 degrees Celsius, it is, however, a long way to Tipperary. “To sit” is a verb and the wooden chairs of the Festspielhaus remind you of that. They are not made for the third act, that takes two hours, of Die Meistersinger. One wishes the old Sachs just shortens himself here. This may be due to the fact that, in the performance of August 7, Michael Volle (an otherwise excellent Sachs) didn't have his pipes available in optimal condition (he excused himself for that at the beginning of the third act) and thus wasn't as convincing as he normally is. It could also be due to the reading of Philippe Jordan which I found somewhat detached. And it could be due to my place in the top of the Festspielhaus where you are not surrounded by sound like in the rest of the hall. Die Meistersinger inevitably did provide its moments of glorious beauty, but in the third act it didn't catch fire. Luckily there was the chorus of Der Bayreuther Festspiele, the great Veit Pogner of Günther Groissböck (who also takes up the role of Fasolt in Das Rheingold this Festspiele) and Klaus Florian Vogt – although I hear in him more a Lohengrin than a Walter von Stolzing (and despite the fact that he was almost outsung by the David of Daniel Behle in the first act).

For me Die Meistersinger was the starter (worthy of a main course) with which I began my visit to the 2017-edition of the Bayreuther Festspiele. One day later, a low Es-chord would welcome me at the banks of the Rhine, taking me on a journey that would bring me, 6 days and almost 14 hours of opera later, to the end of the world.

For me Die Meistersinger was the starter (worthy of a main course) with which I began my visit to the 2017-edition of the Bayreuther Festspiele. One day later, a low Es-chord would welcome me at the banks of the Rhine, taking me on a journey that would bring me, 6 days and almost 14 hours of opera later, to the end of the world.