PARSIFAL IN BAYREUTH: MUSICAL MARVELS IN A SHAKY STAGING

Laufenberg's production is a bit of a bumpy ride but Parsifal in Bayreuth is an experience like few other opera-experiences

Uwe Eric Laufenberg likes his art to connect with topical events. In the week that I saw his Parsifal in Bayreuth, he had a 13-foot statue of Erdoğan placed in Wiesbaden - on the occassion of an art manifestation where he was artistic director. The supposed mockery (the motto of the manifestation was "Bad News") resulted in a statue vandalised with graffiti. The golden sculpture became a magnet for both supporters and opponents of the Turkish (would-be) dictator. It led to a slightly aggressive atmosphere in the public space that was enough, in spite of intentions to use art as a mean to stimulate discussion, to have it removed prematurely.

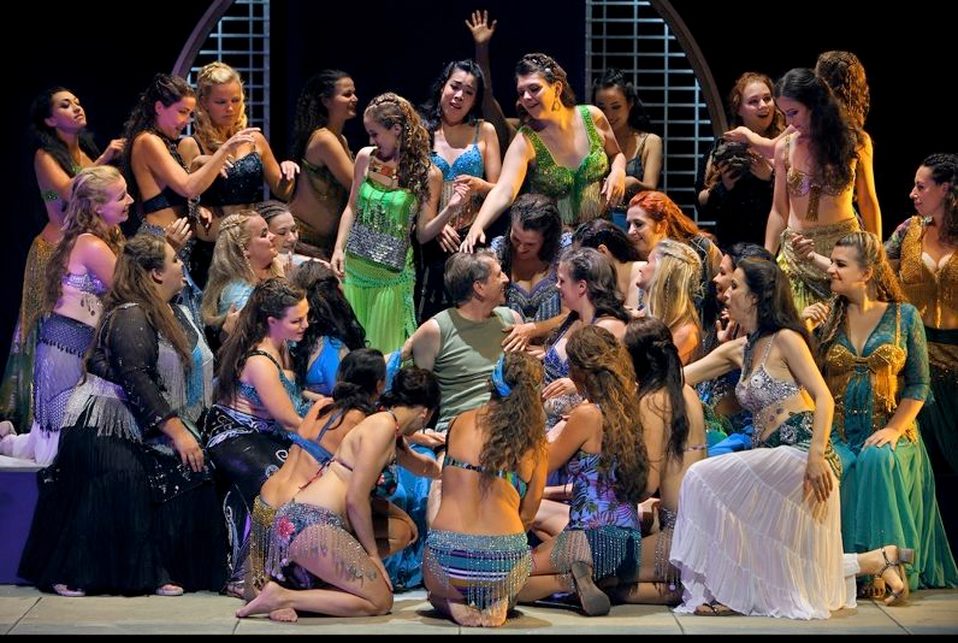

Three years ago, the premiere of Laufenberg's Parsifal in Bayreuth led to additional safety measures in and around the Festspielhaus (including a ban on bringing in cushions, which are now firmly attached to the wooden chairs). The reason for this extra vigilance was the staging of the second act in which Laufenberg presented a part of Klingsor's flower girls as women in chador and another part as belly dancers. The chastity and eroticism of the flower women captured in oriental and religious stereotypes. In addition, Laufenberg used the Christian symbolism with which Wagner impregnated his Bühnenweihfestspiel not so much as a metaphor but primarily to give the grail community its identity. Placed against an Islamic / oriental Klingsor this was a direct reference to the current religious tensions in the world.

Laufenberg had a template ready for a Parsifal production for Oper Köln when Katharina Wagner asked him for the Bayreuther Parsifal for 2016. (Jonathan Meese was removed from the production. He was probably found to be too provocative - a Parsifal who gives the Hitler salute was a risk to be avoided at all times.) Laufenberg based his staging loosely on the film "Des hommes et des dieux". A film that tells the true story of a group of monks in a monastery in Algeria. There they behave in a neutral and service-minded manner towards the local population but are, ultimately, murdered by Islam extremists.

Laufenberg moves the grail community from a castle in Monsalvat to a monastery in the Middle East (in the video during the Verwandlungsmusik in the first act we see that location quite precisely, in Kurdistan, northern Iraq). The monastery houses refugees and every now and then a patrol of (American) soldiers passes by.

In the beginning we see refugees lying on fieldbeds in the monastery, awakened by the grail knights (monks) and summoned to make place. When Parsifal, according to tradition, makes his entry by shooting a swan, a boy in a red t-shirt enters, stumbles and, referring to the iconic image of the dead boy Aylan on the beach of Bodrum, falls and remains lying with his head down. The attention of the grail knights and Gurnemanz to the dead boy shifts to the fate of the dead swan. Here, the death of an animal - in accordance with Schoperhauerian Mitleid - is equated with that of a human being. Gurnemanz blames Parsifal, who is seen as a fool but certainly not pure - despite a cautious suspicion of Gurnemanz in that direction. He invites Parsifal to attend the grail ritual but, if the young man remains mute to the question of what he just has witnessed, he throws the boy out of the monastery - it will take Parsifal 30 years to return.

Laufenberg moves the grail community from a castle in Monsalvat to a monastery in the Middle East (in the video during the Verwandlungsmusik in the first act we see that location quite precisely, in Kurdistan, northern Iraq). The monastery houses refugees and every now and then a patrol of (American) soldiers passes by.

In the beginning we see refugees lying on fieldbeds in the monastery, awakened by the grail knights (monks) and summoned to make place. When Parsifal, according to tradition, makes his entry by shooting a swan, a boy in a red t-shirt enters, stumbles and, referring to the iconic image of the dead boy Aylan on the beach of Bodrum, falls and remains lying with his head down. The attention of the grail knights and Gurnemanz to the dead boy shifts to the fate of the dead swan. Here, the death of an animal - in accordance with Schoperhauerian Mitleid - is equated with that of a human being. Gurnemanz blames Parsifal, who is seen as a fool but certainly not pure - despite a cautious suspicion of Gurnemanz in that direction. He invites Parsifal to attend the grail ritual but, if the young man remains mute to the question of what he just has witnessed, he throws the boy out of the monastery - it will take Parsifal 30 years to return.

This year Günther Groissböck took over the role of Gurnemanz from Georg Zeppenfeld and did so with great conviction. Impressive in voice and stage presence is his well-defined interpretation of Gurnemanz - he made his Gurnemanz-debute two years ago at the Dutch National Opera in Amsterdam - a role that makes one looking forward to his interpretation of Wotan in 2020, when the new Bayreuther Ring is on the programme.

In the second act Laufenberg comes up with a novelty: he gives Amfortas stage time as a prisoner of Klingsor. First cuffed and then freely walking around, it was a choice that turned out to be a poor one. (The portrayal of Amfortas byThomas Mayer aside - Mayer turns the suffering of the king of the grail community into a memorabele torment. ) Klingsor - a fantastic Derek Welton who does justice to the anger, fear and frustration that reign in the evil wizard - makes his entry by spreading a robe to pray to the (imaginary) east. He then use a crucifix (a trophy captured from the grail community I think, one resembles a dildo) to threaten Amfortas and later on Kundry - as if he ritually perpetuates the power he has over them. Parsifal comes in and meets the flower girls. First veiled, when they complain about the fact that Parsifal and his men killed their husbands, and then as harem dancers trying to seduce the young man. It makes the scene of Parsifal's meeting with Klingsors Zaubermädchen a sensual one that ends when Kundry enters and calls Parsifal by his name. With the Kundry of Elena Pankratova we have another member of the cast that excells. In her voice and acting the fate of the woman who mocked Christ on the cross, and thus was condemned to an eternal wandering, finds an interpretation that is equally convincing and haunting . Her Kundry is assertive, seductive and maternal but, especially in the second act, the Regie unfortunately fails her (the Bayreuther Werkstatt, the continuing development of a production after it has been premiered, has not improved that after two years). When Parsifal has his aha-Moment after Kundry's kiss - he sees what the cause of Amfortas's wound is - Kundry has sex with Amfortas who, as a prisoner of Klingsor, apparently can suddenly walk around freely. And when Kundry tries to change Parsifal's mind she has to do so in his absence. Here, the possibility of a dialogue is reduced to a forced monologue that robs us of a possible enthralling interaction between Kundry and Parsifal (Amfortas walking around in the scene where he eventually has sex with Kundry made him look like a ghost. An explanation that is possibly the most satisfying one in search for an answer for his apathetic presence in Klingsor's palace. The compulsive sex with Kundry would then be an act in a shadow world that is merely a visual reminder of the moral depravity into which Amfortas, and with him the grail community, sex after all equals sin, has sunk). Dressed as a commando, Parsifal returns and breaks Klingsor's spear in two. With the cross thus formed, he, in his best Van Helsing imitation, forces the wizard, who as a collector of crucifixes did not bother about a cross more or less, to surrender. It is the end of an act that is marred by poor choices in the direction and therefore fails to add to the emotional impact of the music. That the seductive kiss of Pankratova to Andreas Schager, during the curtain call of the second act, could be considered a dramatic highlight was illustrative for the mess that Laufenberg was offering us here.

In the second act Laufenberg comes up with a novelty: he gives Amfortas stage time as a prisoner of Klingsor. First cuffed and then freely walking around, it was a choice that turned out to be a poor one. (The portrayal of Amfortas byThomas Mayer aside - Mayer turns the suffering of the king of the grail community into a memorabele torment. ) Klingsor - a fantastic Derek Welton who does justice to the anger, fear and frustration that reign in the evil wizard - makes his entry by spreading a robe to pray to the (imaginary) east. He then use a crucifix (a trophy captured from the grail community I think, one resembles a dildo) to threaten Amfortas and later on Kundry - as if he ritually perpetuates the power he has over them. Parsifal comes in and meets the flower girls. First veiled, when they complain about the fact that Parsifal and his men killed their husbands, and then as harem dancers trying to seduce the young man. It makes the scene of Parsifal's meeting with Klingsors Zaubermädchen a sensual one that ends when Kundry enters and calls Parsifal by his name. With the Kundry of Elena Pankratova we have another member of the cast that excells. In her voice and acting the fate of the woman who mocked Christ on the cross, and thus was condemned to an eternal wandering, finds an interpretation that is equally convincing and haunting . Her Kundry is assertive, seductive and maternal but, especially in the second act, the Regie unfortunately fails her (the Bayreuther Werkstatt, the continuing development of a production after it has been premiered, has not improved that after two years). When Parsifal has his aha-Moment after Kundry's kiss - he sees what the cause of Amfortas's wound is - Kundry has sex with Amfortas who, as a prisoner of Klingsor, apparently can suddenly walk around freely. And when Kundry tries to change Parsifal's mind she has to do so in his absence. Here, the possibility of a dialogue is reduced to a forced monologue that robs us of a possible enthralling interaction between Kundry and Parsifal (Amfortas walking around in the scene where he eventually has sex with Kundry made him look like a ghost. An explanation that is possibly the most satisfying one in search for an answer for his apathetic presence in Klingsor's palace. The compulsive sex with Kundry would then be an act in a shadow world that is merely a visual reminder of the moral depravity into which Amfortas, and with him the grail community, sex after all equals sin, has sunk). Dressed as a commando, Parsifal returns and breaks Klingsor's spear in two. With the cross thus formed, he, in his best Van Helsing imitation, forces the wizard, who as a collector of crucifixes did not bother about a cross more or less, to surrender. It is the end of an act that is marred by poor choices in the direction and therefore fails to add to the emotional impact of the music. That the seductive kiss of Pankratova to Andreas Schager, during the curtain call of the second act, could be considered a dramatic highlight was illustrative for the mess that Laufenberg was offering us here.

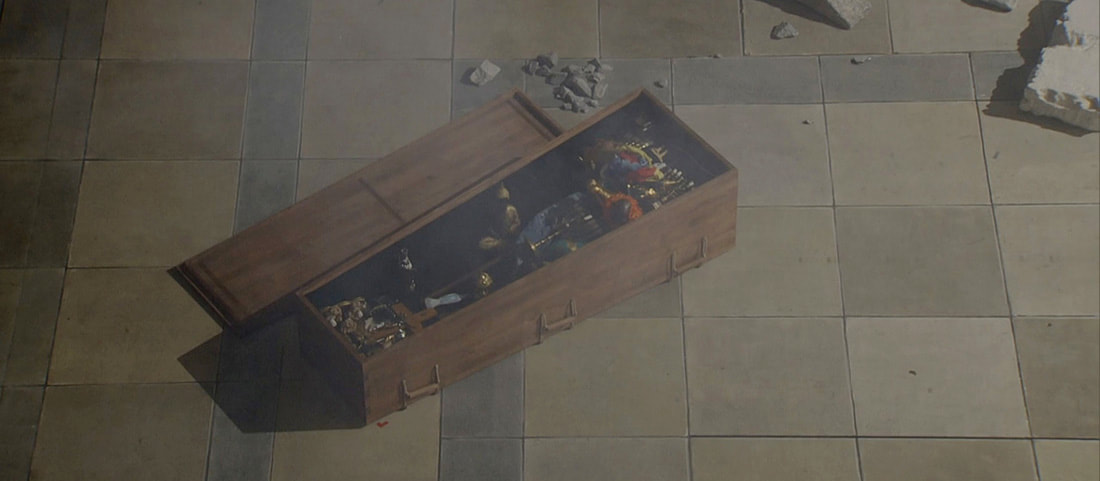

In the third act Parsifal returns to the monastery that now looks dilapidated and is overgrown by vegetation. It took him about 30 years to bring back the spear he recaptured in the second act from Klingsor to the grail community. His voice is less velvetish and his presence is more robust than that of Klaus Florian Vogt, the tenor who sang the role in the first year of this production, but his voice and acting in the role of Parsifal reached in the interpretation of Andreas Schager a good balance (I could not escape the thought of Bayreuth legend Wolfgang Windgassen here). As Parsifal, Schager convincingly transforms from ignorant fool to the man who not only heals the wound of Amfortas but also gives the morally eroded world of the grail community, and with it the world, a reboot By placing the spear-made-into-a-cross in Amfortas's coffin he gives the go-ahead for the burying of all religion symbols. As a sign for people to find back their humanity by overcoming their own religion indoctrinations. A possible message that religion, first and foremost, does not extracts its meaning from symbols, can do without symbolism - and therefore without dogmas.

It is a humanistic conclusion of a production in which Laufenberg interweaves contemporary issues such as the refugee crisis, religious tensions and the wars in the Middle East with Parsifal's story. But the elements that must provide the piece with a topical touch feel forced. The message that Laufenberg wants to send out (benevolence, brotherhood across the boundaries of religion) and reinforces that message, a bit like Captain Obvious, with his scenery (showering together during the Good Friday music, as well as naked women there is room for a naked man this year) might bear witness to good intentions (let's take that as a starting point), but they do not merge well with the character of the piece. A mixture of a Passion and Opera which appeal lies for an important part in the mystical and the mysterious. It feels as if a proper elaboration of the template Laufenberg started working with - an elaboration that had to ensure that all elements of the production would fall into their natural place - had to make way for the will to deliver a message. It are side notes to a production - next year it will be on the Bayreuther programme for the last time - that once again raise the question why it was this Parsifal by Uwe Eric Laufenberg, and not Stefan Herheim's, who was ultimately endowed with a DVD release. God's ways may be mysterious, the ways of the Bayreuther court on the green hill show themselves even more mysterious here.

It is a humanistic conclusion of a production in which Laufenberg interweaves contemporary issues such as the refugee crisis, religious tensions and the wars in the Middle East with Parsifal's story. But the elements that must provide the piece with a topical touch feel forced. The message that Laufenberg wants to send out (benevolence, brotherhood across the boundaries of religion) and reinforces that message, a bit like Captain Obvious, with his scenery (showering together during the Good Friday music, as well as naked women there is room for a naked man this year) might bear witness to good intentions (let's take that as a starting point), but they do not merge well with the character of the piece. A mixture of a Passion and Opera which appeal lies for an important part in the mystical and the mysterious. It feels as if a proper elaboration of the template Laufenberg started working with - an elaboration that had to ensure that all elements of the production would fall into their natural place - had to make way for the will to deliver a message. It are side notes to a production - next year it will be on the Bayreuther programme for the last time - that once again raise the question why it was this Parsifal by Uwe Eric Laufenberg, and not Stefan Herheim's, who was ultimately endowed with a DVD release. God's ways may be mysterious, the ways of the Bayreuther court on the green hill show themselves even more mysterious here.

This year there was a Bayreuth-debute for Semyon Bychkov who took over the baton from Hartmut Haenchen (who had conducted Parsifal for the past two years here). Bychkov, as expected, used somewhat broader tempi than Haenchen (who in his Parsifal performances in Bayreuth had searched for the tempi that Hermann Levi had used for the premiere in 1882, "Everything longer than four hours is one hundred percent wrong," Haenchen had noted on that occassion). Remarkable in that respect was that Bychkov in the programme notes, like Haenchen last year, referred to a letter from Wagner to Liszt in which the former explains to Liszt how to find the right tempi for his operas. (In Lohengrin's premiere in Weimar in 1850, Liszt had been one hour (!) slower than Wagner had intended). Bychkov used a bit more time than Haenchen, not shockingly much, about 15 minutes more on 4 hours of opera, but demanded, by doing so, more of the stamina of the singers - especially in the third act. His orchestral sound was more weighty than the fairytale-, Debussy-kind of colours that Haenchen withdrew from the orchestra. Of the reported small struggles during his first performance in the Bayreuther pit with the typical Bayreuther acoustics, nothing could be noticed at the performance of 25 August. Bychkov's reading was a reading of someone who exactly knew his way in Parsifal's score.

In the weeks leading up to 25 August, I deliberately did not listen to Parsifal. I wanted the event, Parsifal live at the Bayreuther Festspielhaus, to be a stand-alone experience - without being hindered by reflections on tempi and comparisons with other recordings. It succeeded. More than any other opera in the Wagner catalogue, Parsifal (the only opera Wagner composed with the acoustics of the Festspielhaus in mind) benefits from the orchestra pit under the stage. Where in an opera like Meistersinger, with its counterpoint that refers to Bach, the covered orchestra pit almost works against the opera, Parsifal's musical landscape finds in the Festspielhaus its true and (perhaps) only real home. To be able to hear that live is an experience like few other experiences in the world of opera.

In the weeks leading up to 25 August, I deliberately did not listen to Parsifal. I wanted the event, Parsifal live at the Bayreuther Festspielhaus, to be a stand-alone experience - without being hindered by reflections on tempi and comparisons with other recordings. It succeeded. More than any other opera in the Wagner catalogue, Parsifal (the only opera Wagner composed with the acoustics of the Festspielhaus in mind) benefits from the orchestra pit under the stage. Where in an opera like Meistersinger, with its counterpoint that refers to Bach, the covered orchestra pit almost works against the opera, Parsifal's musical landscape finds in the Festspielhaus its true and (perhaps) only real home. To be able to hear that live is an experience like few other experiences in the world of opera.

- Wouter de Moor

THE OTHER OPERA HOUSE IN BAYREUTH

While I was on my (annual) Wagner pilgrimage in Bayreuth, extended with a short Bavarian holiday, I visited the Markgräfliches Opernhaus - an 18th-century opera house that after years of restoration is open for the public again. It appears that this opera house was a gift from Markgräflin Wilhelmina to herself, as a kind of consolation, because she had, contrary to expectations, to settle for the role of Countess instead of becoming Queen of Prussia.

When Richard Wagner was looking for an appropriate place to stage his operas, he ended up in this theater in Bayreuth. Baroque, beautiful and delicate, almost like a doll's house, the place was almost everything that the self-proclaimed composer of the music of the future hated in an opera house. It was, to start with, too small. The space for the orchestra was fit for 30-40 musicians, fine for a Mozart opera but by no means sufficient for a Wagner orchestra of about 100 people. What Wagner did like was the deep stage, 27 meters, where one could suggest extra depth with diorama-like panels. Wagner took up the idea of this extra deep stage for his own, yet to be built, Festspielhaus.

This opera house, which is on UNESCO's world heritage list, has been restored to function as a (baroque) music theatre in the near future (it has 520 seats and, unlike the Festspielhaus, climate control). It feels a bit like walking around in a painting. Very nice but a decoration that Wagner considered more suitable for his bedroom than for his ideal theatre.

Perhaps Wotan and Brunnhilde would feel a bit clastrophobophic in the Markgräfliches Opernhaus, despite all its splendour, but maybe it would be a nice idea to program here, whether or not during the Festspiele, Die Feen, Das Liebesverbot or Rienzi.

When Richard Wagner was looking for an appropriate place to stage his operas, he ended up in this theater in Bayreuth. Baroque, beautiful and delicate, almost like a doll's house, the place was almost everything that the self-proclaimed composer of the music of the future hated in an opera house. It was, to start with, too small. The space for the orchestra was fit for 30-40 musicians, fine for a Mozart opera but by no means sufficient for a Wagner orchestra of about 100 people. What Wagner did like was the deep stage, 27 meters, where one could suggest extra depth with diorama-like panels. Wagner took up the idea of this extra deep stage for his own, yet to be built, Festspielhaus.

This opera house, which is on UNESCO's world heritage list, has been restored to function as a (baroque) music theatre in the near future (it has 520 seats and, unlike the Festspielhaus, climate control). It feels a bit like walking around in a painting. Very nice but a decoration that Wagner considered more suitable for his bedroom than for his ideal theatre.

Perhaps Wotan and Brunnhilde would feel a bit clastrophobophic in the Markgräfliches Opernhaus, despite all its splendour, but maybe it would be a nice idea to program here, whether or not during the Festspiele, Die Feen, Das Liebesverbot or Rienzi.

See also: