Der Bayreuther Ring from 2017

Frank Castorf and the theater of deconstruction

My journey from Nibelheim to the end of the world begins on Tuesday, August 8, 2017. That afternoon at six o'clock a low Es chord swells from the pit under the stage and changes the Festspielhaus into a virtual version of the Rhine. A few minutes later, my ears will join the pentatonic melodies of the daughters of the Rhine. Wagner loved the pentatonic scale, he used it on several occasions, for more than a few leitmotifs, in Der Ring. It's perhaps because of that, that my ears - that grew up with blues-based pop and rock music - so easily picked up his music.

In possession of just a little imagination, the trip alongside the four opera's of Der Ring des Nibelungen is already hallucinant enough. It is therefore immensely fascinating to get acquainted with a new production – to see what a theater maker has done with Wagner's tetralogy. In the case of Frank Castorf, the concept “new” has to be put into perspective. This year, in 2017, his Ring has its fifth and final installment in Bayreuth. Controversial is the first thing one thinks of - not entirely out-of-character with the tradition of the Festspiele - when it comes to label the Castorf-Ring.

Das Rheingold commences at the Golden Motel with a gas station at Route 66. In the swimming pool at the motel, three women, light-o'-love, hang up the laundry. Alberich sleeps at the pool. The spectator, familiar with the story, runs a find-and-replace routine on the things he sees on stage. The pool is the Rhine, the prostitutes are the Rheintöchter, the laundry rack is the world ash tree. With the entrance of Wotan we see he is a pimp/mobster. Nothing strange sofar. It is not the depiction of the Rheintöchter as prostitutes and Wotan as a pimp that can be considered controversial. It has been done many times since the groundbreaking Chéreau production of 1976 (it is in fact slightly overdue). When Alberich robs the Rhine gold, the daughters of the Rhine, freed from their guarding duties, decide to hit the lights and call it a party. It is Castorf's first (and certainly not last) direction that diametrically opposes text and music. Route 66 becomes a highway to alienation. Five years ago, with the premiere of this production, it was this free, associative use of the text that stirred the biggest controversy. An approach in which Castorf breaks apart the text & music from the scenery on stage. When imagining Wagner's Ring, he is not interested in maintaining the cohesion between scenes. The long arches of Wagner's skillfully and meticuliously build-up music drama, that unmatched amalgam of text and music, meet in Castorf a man with a box cutter. By cutting the link between images and music, Castorf reduces Wagner's music to a kind of soundtrack. Wagner's music, perfectly capable of standing on its own, always does something to whatever kind of scenery – al be it in the most superficial way. It reminds me of the first associations I had with Wagner's music, that with film music, and the idea that I once had of Wagner's music dramas, that they were some kind of proto-movies. 19th century theater dramas, made with the means of its time, that, if only they were to be made with 20th century means, certainly had to turn out as movies. It was a gross underestimation of Wagner's Gesamtkunstwerk. The genius with which the music in the Gesamtkunstwerk supports the text, brings out all that's in the story and provides it with texture, transcends a movie-soundtrack many times. The music in Der Ring, that cathedral of leitmotifs, ruined me for many a film soundtrack.

In possession of just a little imagination, the trip alongside the four opera's of Der Ring des Nibelungen is already hallucinant enough. It is therefore immensely fascinating to get acquainted with a new production – to see what a theater maker has done with Wagner's tetralogy. In the case of Frank Castorf, the concept “new” has to be put into perspective. This year, in 2017, his Ring has its fifth and final installment in Bayreuth. Controversial is the first thing one thinks of - not entirely out-of-character with the tradition of the Festspiele - when it comes to label the Castorf-Ring.

Das Rheingold commences at the Golden Motel with a gas station at Route 66. In the swimming pool at the motel, three women, light-o'-love, hang up the laundry. Alberich sleeps at the pool. The spectator, familiar with the story, runs a find-and-replace routine on the things he sees on stage. The pool is the Rhine, the prostitutes are the Rheintöchter, the laundry rack is the world ash tree. With the entrance of Wotan we see he is a pimp/mobster. Nothing strange sofar. It is not the depiction of the Rheintöchter as prostitutes and Wotan as a pimp that can be considered controversial. It has been done many times since the groundbreaking Chéreau production of 1976 (it is in fact slightly overdue). When Alberich robs the Rhine gold, the daughters of the Rhine, freed from their guarding duties, decide to hit the lights and call it a party. It is Castorf's first (and certainly not last) direction that diametrically opposes text and music. Route 66 becomes a highway to alienation. Five years ago, with the premiere of this production, it was this free, associative use of the text that stirred the biggest controversy. An approach in which Castorf breaks apart the text & music from the scenery on stage. When imagining Wagner's Ring, he is not interested in maintaining the cohesion between scenes. The long arches of Wagner's skillfully and meticuliously build-up music drama, that unmatched amalgam of text and music, meet in Castorf a man with a box cutter. By cutting the link between images and music, Castorf reduces Wagner's music to a kind of soundtrack. Wagner's music, perfectly capable of standing on its own, always does something to whatever kind of scenery – al be it in the most superficial way. It reminds me of the first associations I had with Wagner's music, that with film music, and the idea that I once had of Wagner's music dramas, that they were some kind of proto-movies. 19th century theater dramas, made with the means of its time, that, if only they were to be made with 20th century means, certainly had to turn out as movies. It was a gross underestimation of Wagner's Gesamtkunstwerk. The genius with which the music in the Gesamtkunstwerk supports the text, brings out all that's in the story and provides it with texture, transcends a movie-soundtrack many times. The music in Der Ring, that cathedral of leitmotifs, ruined me for many a film soundtrack.

Frank Castorf turns the Rhine gold into oil. Oil as equivalent of power. Fafner and Fasolt (strong, menacing roles from Karl-Heinz Lehner and Günther Groissböck) are a team of thugs who don't shy away from beating up the gas station with their baseball bats. Loge is a pimp-like type that shows Patric Seibert, Castorf's assistant who has a non-speaking role in all four Ring-operas, pictures of the robbery of the Rhine gold. Castorf shows himself harsh on those who want a Ring to dream on - on those who want Wagner as the perfect drug. He shows no mercy for those who want their Ring served with giants, dwarfs and a dragon. Also Walhalla is non-existent (at least in Das Rheingold). It only exists in transcendental terms, as metaphor. "Imagination instead of Fantasy" is Castorf's adage. His Ring depicts a tale of sex and violence within human relationships. It's a story with stunnning images by Aleksandar Denić. The turning platform that allows open-curtian scene changes in all four Ring Opera operas ensures variation and coherence. It's also a Ring in which Castorf shows himself an unreliable narrator. For example, the scene where Wotan and Loge descend to Nibelheim, starts with Alberich and Mime being captured while in the libretto Alberich is captured at the end of that scene. The viewer, who knows the story, doesn't know what he's really looking at. He wonders how to value the things he is witnessing. It makes the Castorf-Ring by times a frustrating, annoying event. For those in the audience who are looking for the intoxication of the Wagner theater (don't we all?), Castorf feels sometimes like cold turkey, a bully denying us our natural need for goose bumps. He pushes Wagner aside and stands between the story and the audience. Whether or not the questions he raises by doing so, make up for what he breaks up so badly, remains a question that comes with an ambiguous answer. It surely fascinates me. Makes me rethink, for instance, the relationship between images and music in opera (and beyond). Part of the richness of a theater experience is the possibility to attend something that you may not like. Something that doesn't lead to instant satisfaction. A theater maker who makes his audience part of a personal search and gives room for one's own interpretation and (meta-)conclusions can be more satisfying in the end than a director who just wants to impress. A Wagner opera should be more than just an escape from reality for a few hours but the challenges Castorf confronts his public with are not spent on everyone. Several people leave during Das Rheingold (and that's not because they all have to go to the bathroom).

Today is my day. You can call me Wednesday.

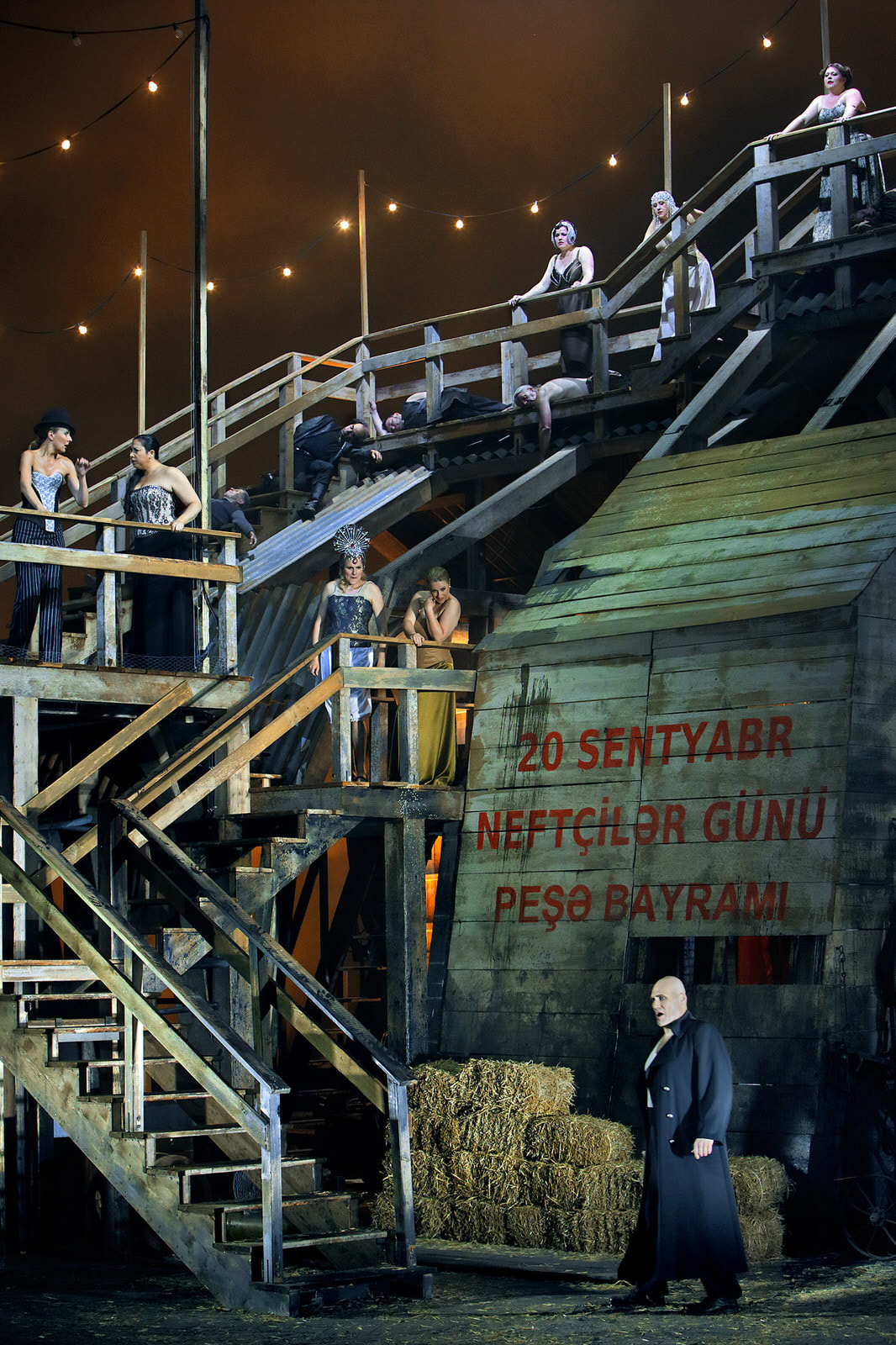

In Die Walküre, Castorf is back on track. After the deconstruction of Das Rheingold, Die Walküre follows a more or less straight story line. Siegmund (Christopher Ventris) falls in love with his lost-thought sister Sieglinde (Camilla Nylund) who is married with Hunding (Bayreuth veteran Georg Zeppenfeld). The oil from Das Rheingold returns, this time in the form of an oil winning plant in Azerbaijan, and the role of Wotan goes, in the spirit of Castor's breaking-up techniques, from Iain Paterson (Das Rheingold) to John Lundgren. Together with the Brünnhilde of an outstanding Catharine Foster, he makes up for an unforgettable evening. It was during Die Walküre that – in the battle between Castorf, the Russian texts on stage and the music – I decisively took sides with the latter. By the end of the third act I couldn't care less about oil fields in Azerbaijan. Text and music of Wotan, who first turns his back on Siegmund and then kisses his favorite daughter Brünnhilde into an eternal sleep, go as deep as love and lost can go. It was during Wotan's Farewell that the insight sank in that a director, regardless of his efforts, could never beat Wagner (although I found the kiss Wotan gives Brünnhilde, like it was a date going wrong, genuinly funny). I will remember the 'Bayreuther' Walküre of 2017 for a long, long time.

After Die Walküre follows Siegfried. The character Siegfried is the strange idea Wagner had of a hero. The man is an ignorant fool, a child of nature, a kind of Caspar Hauser, a boy who doesn't know fear (and for that reason can not be brave). He becomes afraid when he first sees Brünnhilde. "Das ist kein Mann!" the boy shouts - like a Doctor Who-fanatic thrown out of his comfort zone. Siegfried, son of the incestuous relationship between Siegmund and Sieglinde, falls in love with Brünnhilde, who is actually his aunt (Wagner likes to keep it in the family). Siegfried comes after Siegmund, the real hero of the whole cycle. Siegmund is the one who changes Brünnhilde's mind. Deeply impressed by Siegmund's love for Sieglinde – Siegmund rejects the heavenly pleasures of Walhalla because he wants to stay with Sieglinde, even if it is in earthly distress – Brünnhilde decides to disobey Wotan. She steps away from the path of the chief god and eventually brings down the world of the gods (with all its corruption and abuse of power).

The place where Siegfried is raised by Mime is that of a communist Mount Rushmore (Marx, Lenin, Stalin and Mao instead of Washington, Jefferson, Teddy Roosevelt and Lincoln). It may say something about the idea that Castorf has of Siegfried: a revolutionary, a weapon against the capitalism of the gods. Siegfried is a so-called independent hero whose biggest tragedy is that he is just as good an instrument as anyone else in Der Ring. The Siegfried of Castorf makes no effort to win our sympathy. His is a bully that beats up a bum for no particular reason, an one-dimensional egghead who sexual abuses Rheintöchters and, had it not be for Brünnhilde, would have had it with the Waldvogel.

The place where Siegfried is raised by Mime is that of a communist Mount Rushmore (Marx, Lenin, Stalin and Mao instead of Washington, Jefferson, Teddy Roosevelt and Lincoln). It may say something about the idea that Castorf has of Siegfried: a revolutionary, a weapon against the capitalism of the gods. Siegfried is a so-called independent hero whose biggest tragedy is that he is just as good an instrument as anyone else in Der Ring. The Siegfried of Castorf makes no effort to win our sympathy. His is a bully that beats up a bum for no particular reason, an one-dimensional egghead who sexual abuses Rheintöchters and, had it not be for Brünnhilde, would have had it with the Waldvogel.

The Waldvogel – an animal, a creature of nature, part of the world that has not been corrupted by civilization – is portrayed by a woman who, dressed up for carnival, is lost in the human world. With Castorf nothing is free from the human stain. Nature is infected too.

The role of Siegfried fits Stefan Vinke like a glove. I find Vinke's portrayal of Castorfs maniacal version of Siegfried so convincing that I can hardly resist the idea that the man in reality has the same kind of issues as his counterpart on stage. This Siegfried does not kill a dragon. Here Fafner does not transform. The dragon remains a metaphor. The death of Fafner, shot by Siegfried with a kalashnikov, is an extremely violent (and noisy) scene. Patrice Chéreau gave the Wagnerian world of the Ring a shot in the arm by showing (or reminding) us that we are witnessing a drama of human rather than godlike dimensions. With Siegfried's killing of Fafner, Castorf takes this to the next level. We are witnesses of brutal murder. Stripped from all its heroism and mythology only cold and raw human violence remains. Both theatrical- and dramatical-wise it worked very well for me. Instead of the dragon, we have crocodiles at Berlin Alexanderplatz (crawling out of the sewer after American bombs have hit the Berliner Zoo at the end of World War II).

At the end of the love duet with Brünnhilde, Siegfried rescues the Waldvogel, now stripped of the wings of her carnival suit, from the mouth of a crocodile. A direct reference to Pina Bausch's ballet "The Legend of Chastity". An act of egoism rather than heroism. After the rescue Siegfried forces himself onto the girl and tries to kiss her. Not on Brünnhilde's watch. With a firm slap in his face, Brünnhilde lets him know that she did not made her way through the love duet just to be left alone by him. With full force she kisses him – the dragon slayer, who isn't really a dragonslayer but a cold blooded fruitcake with a kalashnikov – to show him, and all of us, who really is in charge here.

The role of Siegfried fits Stefan Vinke like a glove. I find Vinke's portrayal of Castorfs maniacal version of Siegfried so convincing that I can hardly resist the idea that the man in reality has the same kind of issues as his counterpart on stage. This Siegfried does not kill a dragon. Here Fafner does not transform. The dragon remains a metaphor. The death of Fafner, shot by Siegfried with a kalashnikov, is an extremely violent (and noisy) scene. Patrice Chéreau gave the Wagnerian world of the Ring a shot in the arm by showing (or reminding) us that we are witnessing a drama of human rather than godlike dimensions. With Siegfried's killing of Fafner, Castorf takes this to the next level. We are witnesses of brutal murder. Stripped from all its heroism and mythology only cold and raw human violence remains. Both theatrical- and dramatical-wise it worked very well for me. Instead of the dragon, we have crocodiles at Berlin Alexanderplatz (crawling out of the sewer after American bombs have hit the Berliner Zoo at the end of World War II).

At the end of the love duet with Brünnhilde, Siegfried rescues the Waldvogel, now stripped of the wings of her carnival suit, from the mouth of a crocodile. A direct reference to Pina Bausch's ballet "The Legend of Chastity". An act of egoism rather than heroism. After the rescue Siegfried forces himself onto the girl and tries to kiss her. Not on Brünnhilde's watch. With a firm slap in his face, Brünnhilde lets him know that she did not made her way through the love duet just to be left alone by him. With full force she kisses him – the dragon slayer, who isn't really a dragonslayer but a cold blooded fruitcake with a kalashnikov – to show him, and all of us, who really is in charge here.

With all the possibilities Frank Castorf gives the audience to associate with movies, theater and modern culture, Berlin Alexanderplatz also brings up the name of filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Fassbinder, a big child according to the people close to him, once said that you must have yourself twice in order to become a complete person. It was problably his excuse for behaving in Jekyll-Hyde kind of ways. Referring to Siegfried one can only concludes that Siegfried has himself only once, as Mr. Hyde. His is not a complete person. So much for the Wagnerian hero.

Castorf doesn't care too much about the continuity between the various operas of the Ring but he brings in a grey caravan that after Das Rheingold returns in Die Walküre and Siegfried (and later in Götterdämmerung). It is a place of transformation: a place where Alberich in Das Rheingold shapeshifts, using the Tarnhelm, in a snake and a toad. It is used as a house: a place where Brünnhilde and Siegfried live together. It's also a place in which what's happening inside can only be made visible to the public eye by the cameras of reality-tv (another thing that returns after Das Rheingold). It is a place where things happen that may not bear the light of day.

From all references to movies David Lynch's Lost Highway is one worth mentioning (especially when it comes to alienating storytelling techniques). Gangster movies are the obvious other one. In Götterdämmerung one film reference can't be unlooked. The use of Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin's baby carriage is, in fact, all too obvious. It gives this Ring it own Odessa Steps scene. Castorf is not holding back on stage noises (besides sitting on them, chairs are very useful to throw with) but at the end of the second act of Götterdämmerung he crosses a line. With the pram pushed from the stairs and Gunther (a very convincing Markus Eiche) angrily beating a hammer (after the conspirators Hagen-Brünnhilde-Gunther have decided Siegfried must die), Castorf engages in musical hooliganism. (It's like Gunther forges - out-of-tune & out-of-rhythm - like a kind of would-be Siegfried a would-be sword). It is Castorf's ultimate attempt to drag the spectator out of the Wagnerian sound world.

Castorf doesn't care too much about the continuity between the various operas of the Ring but he brings in a grey caravan that after Das Rheingold returns in Die Walküre and Siegfried (and later in Götterdämmerung). It is a place of transformation: a place where Alberich in Das Rheingold shapeshifts, using the Tarnhelm, in a snake and a toad. It is used as a house: a place where Brünnhilde and Siegfried live together. It's also a place in which what's happening inside can only be made visible to the public eye by the cameras of reality-tv (another thing that returns after Das Rheingold). It is a place where things happen that may not bear the light of day.

From all references to movies David Lynch's Lost Highway is one worth mentioning (especially when it comes to alienating storytelling techniques). Gangster movies are the obvious other one. In Götterdämmerung one film reference can't be unlooked. The use of Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin's baby carriage is, in fact, all too obvious. It gives this Ring it own Odessa Steps scene. Castorf is not holding back on stage noises (besides sitting on them, chairs are very useful to throw with) but at the end of the second act of Götterdämmerung he crosses a line. With the pram pushed from the stairs and Gunther (a very convincing Markus Eiche) angrily beating a hammer (after the conspirators Hagen-Brünnhilde-Gunther have decided Siegfried must die), Castorf engages in musical hooliganism. (It's like Gunther forges - out-of-tune & out-of-rhythm - like a kind of would-be Siegfried a would-be sword). It is Castorf's ultimate attempt to drag the spectator out of the Wagnerian sound world.

Disconnecting images from text & music reduces Wagner's drama (by times) to a play with just a soundtrack. It's theater over drama. But at the end of Götterdämmerung Castorf doesn't even manage that. The man of deconstruction seems to be out of ideas and from Siegfried's Trauermarsch on things really go downhill. During the Trauermarsch we see a video of Hagen (Stephen Milling), taking a stroll in the woods. Looking for contemplation or whatever it is he is doing. After the clever use of video in the previous operas, this is like a dull karaoke video without lyrics. Fortunately, there is Catharine Foster who, from the Immolition scene on, brings home a great ending. That ending is the result of Brünnhilde's revenge on the world that has deceived her. No weak Italian emergency exits here by, for example, jumping from a tower (Tosca) but the real deal; destroy the world and nothing less. Alas in visually depicting that end Castorf is a bit half-arsed. We don't see Walhalla (The New York Stock Exchange) burning. The love-motif and the Erlösung-motif that shows up in Wagner's final tapestry of sound when the world ends suggest the promise of a new beginning, but in this staging the world doesn't really end. We end up seeing Hagen staring into an oil drum with fire (his own little Mount Doom) where the ring is thrown in. I close my eyes and leave it to my imagination. The music under the baton of Marek Janowski (last year, at 77, he came to Bayreuth despite his contempt for modern opera stagings) does the rest. If the end of the world sounds as good as Götterdämmerung I'm in.

After the end of the world there is a new beginning. The liberation of the past. A liberation that comes with a warning because we have succeeded in escaping the world but are we able to escape ourselves? Are we able to prevent what brought us here in the first place? The end cloaked itself in a gorgeous dress of sound. It's the attraction of the theater that the physical consequences of apocalyptic fantasies do not materialize. After Götterdämmerung, after world's end, I walk from the green hill back to the city center with the woman I have met in the Festspielhaus. Besides Wagner, she is into heavy metal and tango. At the empty, dark market square of Bayreuth we dance a tango. We dance in silence. A cab driver drives up and parks his car right next to us. His car radio plays "7 seconds" by Neneh Cherry & Youssou N'Dour. He turns up the volume. We dance along. Afterwards he applauses. I thank him for being a DJ for us. Outside it's Sunday, tomorrow it's Monday, the beginning of a new week, the beginning of a new world.

After the end of the world there is a new beginning. The liberation of the past. A liberation that comes with a warning because we have succeeded in escaping the world but are we able to escape ourselves? Are we able to prevent what brought us here in the first place? The end cloaked itself in a gorgeous dress of sound. It's the attraction of the theater that the physical consequences of apocalyptic fantasies do not materialize. After Götterdämmerung, after world's end, I walk from the green hill back to the city center with the woman I have met in the Festspielhaus. Besides Wagner, she is into heavy metal and tango. At the empty, dark market square of Bayreuth we dance a tango. We dance in silence. A cab driver drives up and parks his car right next to us. His car radio plays "7 seconds" by Neneh Cherry & Youssou N'Dour. He turns up the volume. We dance along. Afterwards he applauses. I thank him for being a DJ for us. Outside it's Sunday, tomorrow it's Monday, the beginning of a new week, the beginning of a new world.