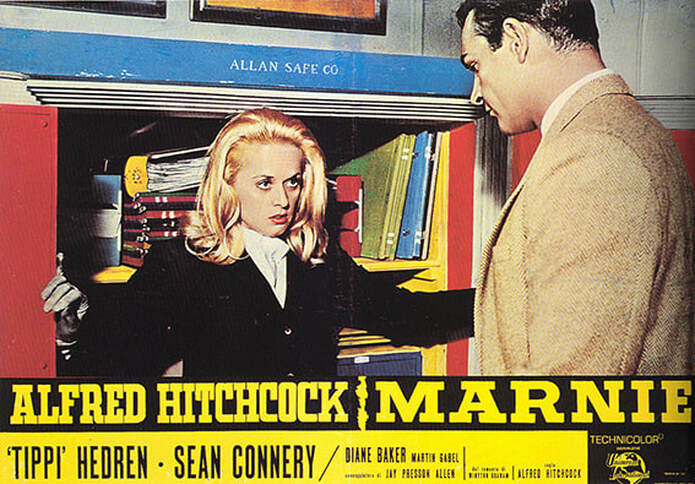

"It may sound far-fetched to compare a dramatic talkie (movie with sound) with opera, but there is something in common. In opera quite frequently the music echoes the words that have just been spoken. That is one way music with dialogue can be used." - Alfred Hitchcock (1934) Opera and movies are intertwined. Once the movie theater manifested itself as a kind of 20th century reincarnation of the opera house, their influence on each other showed itself significant (George Lucas' reference to Star Wars as a space opera is illustrative). From opera, movies lended the diva. Sometimes literally. From Geraldine Ferrar in DeMille's movie-adaption of Carmen (1915) to Maria Callas in Pasolini's Medea (1969). In a silent movie opera star Ferrar could not be heard as a singer but her appareance and appeal alone were big enough to draw a large audience. One didn't have to hear her voice to hear it. The appareance of a famous singer on a silver screen came with implied vocalization. Opera inspired movie makers how to use music as a support to moving pictures and opera showed movie makers the power of a diva. In the case of Geraldine Ferrar the diva was given a new audience outside the theater and concert halls. One very famous, and notorious, movie director that had his ways with divas was Alfred Hitchcock. Hitchcock combined his craftmanship for making movies with his personal obsessions, demons and preoccupations. Like many good artists his personal demons were of inspiration for his art. Limiting the area of the exploitation of one's shortcomings to art, away from society, is what separates the artist from the criminal and it is there where the memory on Hitch is stained. As movie director he crossed a few lines. His obsession for divas, preferably blond, his fascination for the female protagonist in his movies, led to 'harassment in the workplace' as Tippi Hedren (actress for Hitchcock in The Birds and Marnie) would testify years later. Hitchcock's movies, although they certainly carry the stamp of the era they were made in, stood the test of time. His behaviour didn't; the time in which he made the work that saved his name for posterity, saved him from a certain #MeToo. From the opera house to a movie theater back to the opera house. From composer Nico Muhly and librettist Nicholas Wright comes Marnie. Marnie tells a story that is, of course, best known by the movie (from 1964) of Alfred Hitchcock but more than on the movie, the opera is based on the book by Winston Graham. It's Muhly's third opera (after Dark Sisters and Two Boys) and its first opera based on a book (Dark Sisters and Two Boys were made after real-life events). More than Hitchcock's movie the opera follows Graham's storyline. The result is a (techni)colorful production by Michael Mayer that is as filmish as Hitchcock's movie. It is an enthralling excursion into a world of a woman that makes herself a living by stealing from her employers. It's a story about compulsory behaviour with a trauma at its core.  Marnie is a woman, trapped between the trauma of her youth and the social codes of her time. The story, set in England in the 50s, begins with Marnie stealing from her employer Strutt. There she first meets Mark Rutland, a business man who lets his his eye fall on her immediately. He will blackmail her into marriage when she applies for a job at his company. Threatening to expose her as being a thief, Rutland manages to get the thing he wants. (In a time and society in which women are hardly more than commodities to men - as wife, prostitute or mother -, referring to a wife as a "thing", as cold and rude as it sounds, is perhaps uncannily apt.) Marnie might be the one who violates the law but nobody is innocent is this story. She is wanted, by Mark Rutland (baritone Christopher Maltman in a role that shows Rutland much more vulnerable than Sean Connery does in the movie) and his brother Terry (countertenor Ienstyn Davies who, like in Thomas Ades's Exterminating Angel, plays an arrogant and bourgeois character). Terry tells his brother Mark like it is (accusing him of using Marnie as his slave) but more than a righteous mind he probably is a bad sport. (He is hurt by Marnie's rejection - it makes his true motives for his quest for truth highly questionable, he is just as bounded to his entitlement as his brother.) The trauma of her youth lies at the root of Marnie's facade of hiding behind different characters. Next to Isabel Leonhard as Marnie, those characters, personages of the mind, are portrayed by four actresses/singers that function as an Marnie's inner choir. A source of contemplation and a depiction of the past that Marnie carries with her. In the staging we see both straight forward storytelling and a more abstract representation of elements of the story. The police men that are on Marnie's trail are not represented by characters of name but by dancers who serve, in 1950s coats and trench hats, as an artist impression of the arm of the law. On another occasion the ballet of men stage a choreography, imaging the dynamics of a foxhunt (in which no fox or horse is in sight). In that fox hunt Marnie is supplied with a beautiful aria. A highlight in the opera. An embellishment of the moment that is key in the story and in the depiction of Marnie's character. In the foxhunt her horse Forio, the only subject worthy of her love, will get mortally wounded. She will not commit her love to anyone or anything else afterwards. Nico Muhly delivers the story of Marnie in fluent music that echoes his former collaborations with Philip Glass. The inevitable traces of minimal music are confined, enough to save his score from becoming a descent into arperggio-hell. The result is dissonant yet accessible. With a staging that is as accessible as an arthouse movie. An opera production that is a culmination of music, drama and theater that challenges the audience yet invites it to take the trip to a world of love, deceit and self-determination. A world that justifies the opera its own place, away from Hitchcock's movie. More than in Hitchcock's film, the opera delves into the possibilities to use image and sound in a more abstract way, it results in a world of Marnie that is more graphic to the mind. More than just creating an atmosphere Muhly pays attention to the music as a counterpart to the text, as an extra layer to the storytelling. The musical score leaves the orchestra room for concerto moments. Moments in which the music becomes more that just the forward moving vessel that brings the story home. Moments in which solo instruments claim their part. Like the hobo who serve as an inner voice and deliver musical motives of contemplation. Also for those who will go to see this opera with Hitchcock's film as main point of reference (and who doesn't?), the ghost of Bernhard Herrmann's soundtrack, fantastic as it is, will not likely come to haunt him/or her. Amidst the music and the drama it is the title role of Isabel Leonard that shines. Every bit a movie star in her own right, Leonard's interpretation of Marnie makes the tragic and the strenght of Marnie almost tangible. From a victim of circumstances she becomes a woman on the road to self-discovery. Like the book, that is written from the "I"-perspective, the opera sees the story through her eyes. It is a perspective of the unreliable narrator because Marnie is anything, willingly and unwillingly, but bound to the truth. The awareness of the audience of this adds significantly to the realm of suspense and alienation. One enters a world in which things eventually are not what they seem to be. When the end comes and the plot unfolds itself - after the true nature of her trauma is exposed - and Marnie has to face the music (pun intended) she can choose, for the first time in her life, her own path. The end of the story can be looked upon as more positively than how the writer originally intended it. It is an end in which the woman, when everything is over, ultimately determines her own future. A woman who is, in her own words, free despite (spoiler alert) the fact that the police finally gets to her. After her attempts to break free from the patriarchal clutches of society, the handcuffs of the police are merely uncomfortable, her newly gained awareness and self-esteem can be seen as nothing less than a triumph. Earlier in the story, Marnie shows herself as a woman who wants to be independent. And, regardless of her actions being justifiable, she claims her right to be so. She releases a powerful "No Means No" when she defends herself against Mark Rutland's advances. A sign of strength that resonates with the present time of #MeToo. A time in which the voice that had been silenced for many years finally claims its rightful place in the public discourse. Although an opera usually is more emotional-driven than plot-driven - it uses music rather than plot twists to engage - this production differs enough from the movie to surprise those solely familiar with the movie on the area of plot. Its music and staging makes it into a piece of convincing theater, worthy of anything the master of suspense, Hitchcock himself, could come up with. Marnie (Nico Muhly), production for the New York Metropolitan, seen in Pathé Opera - Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed