|

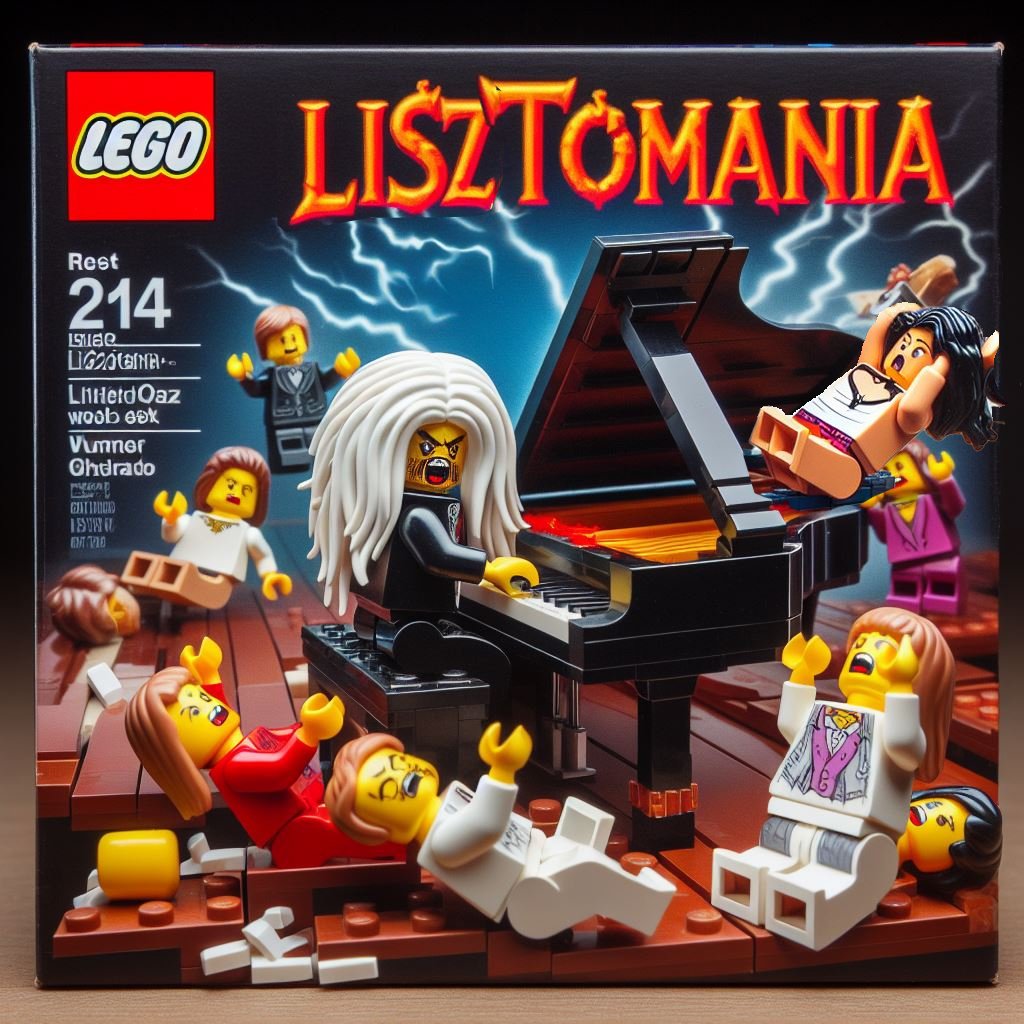

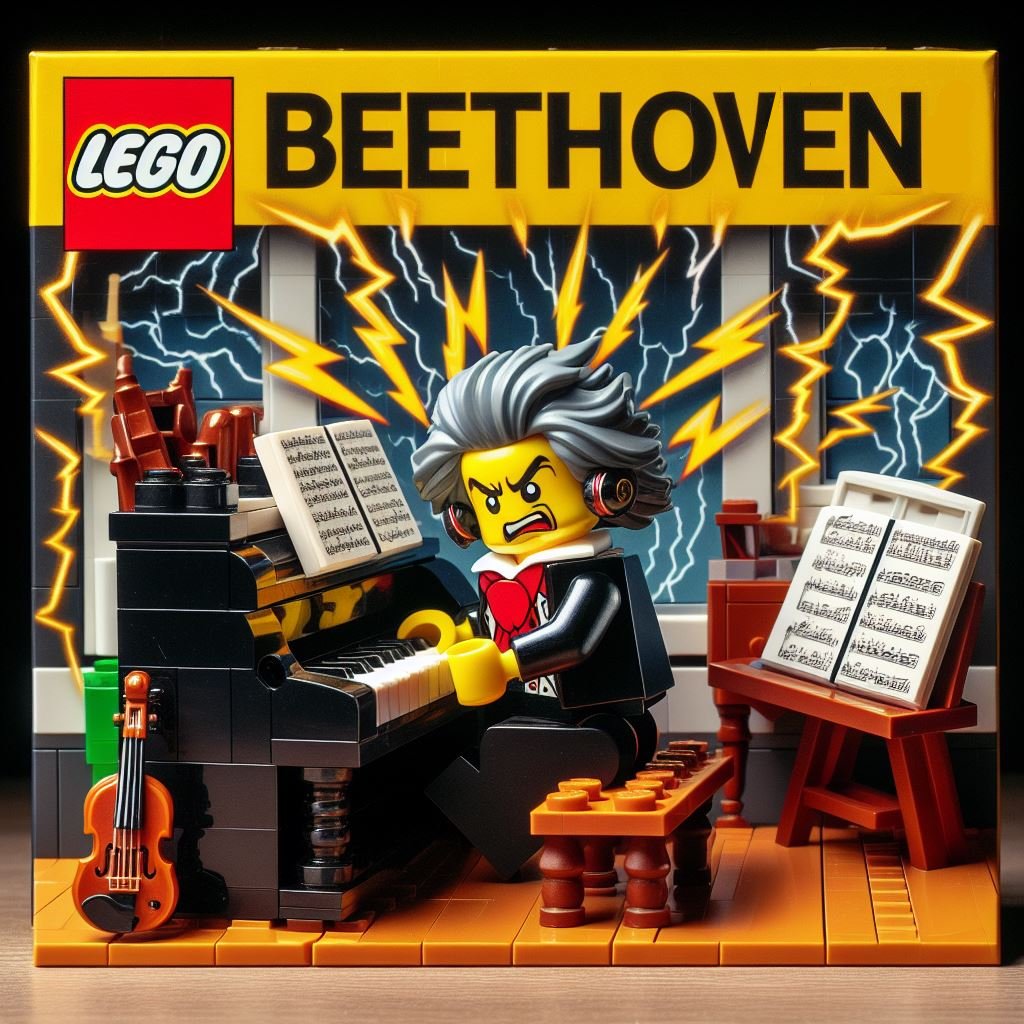

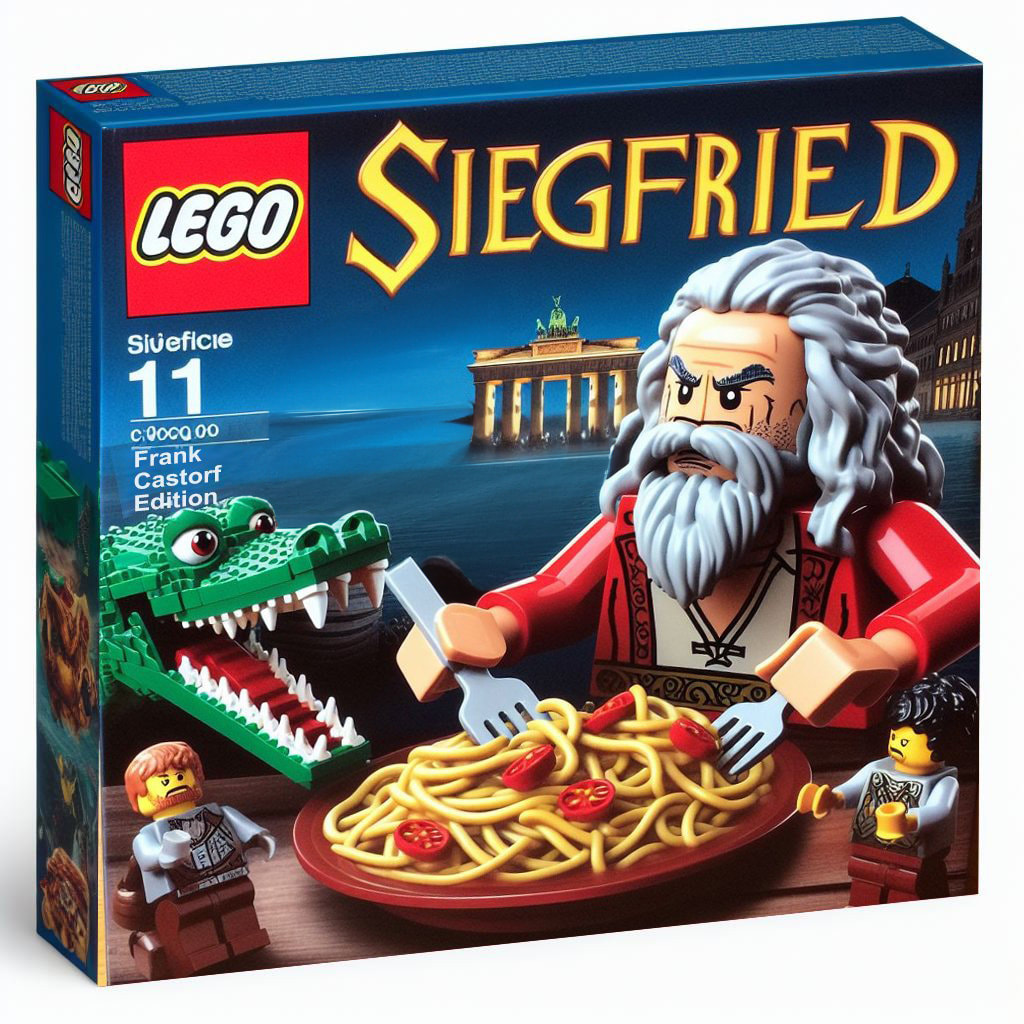

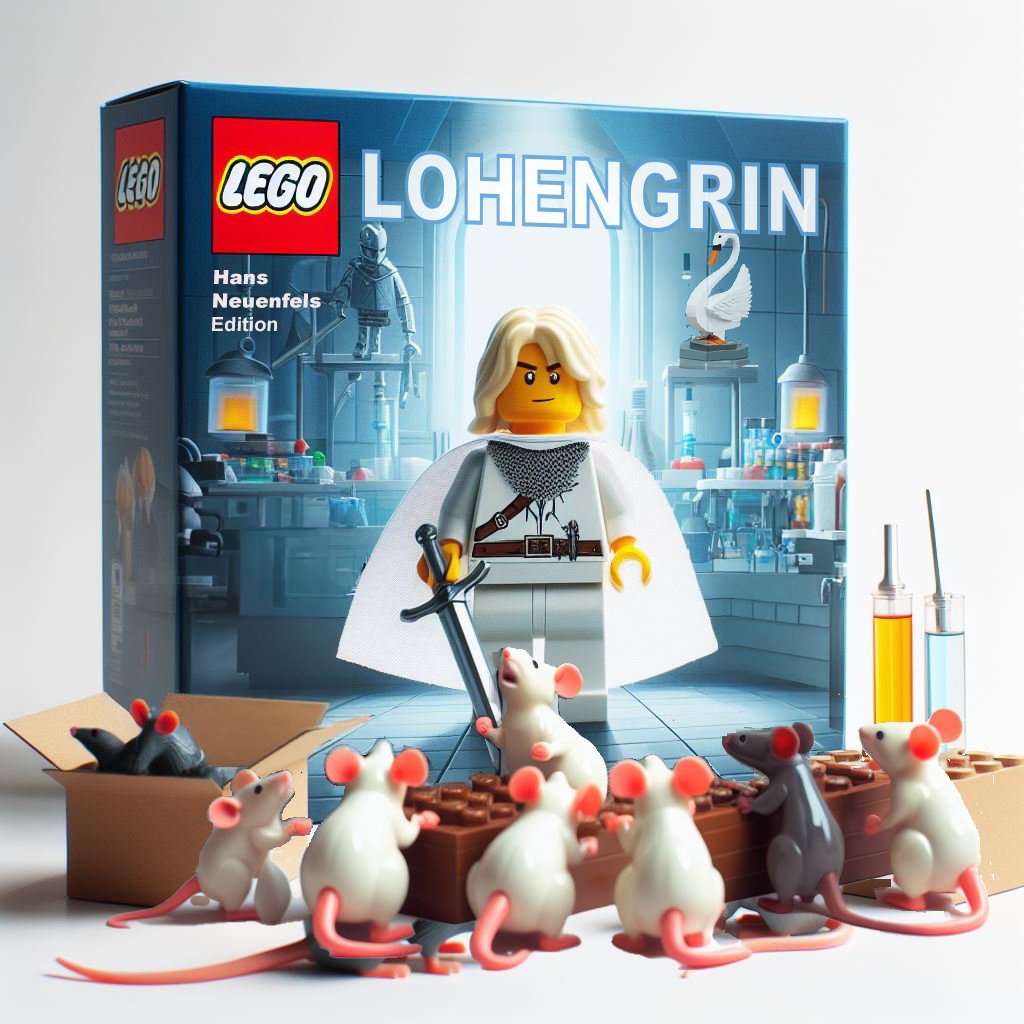

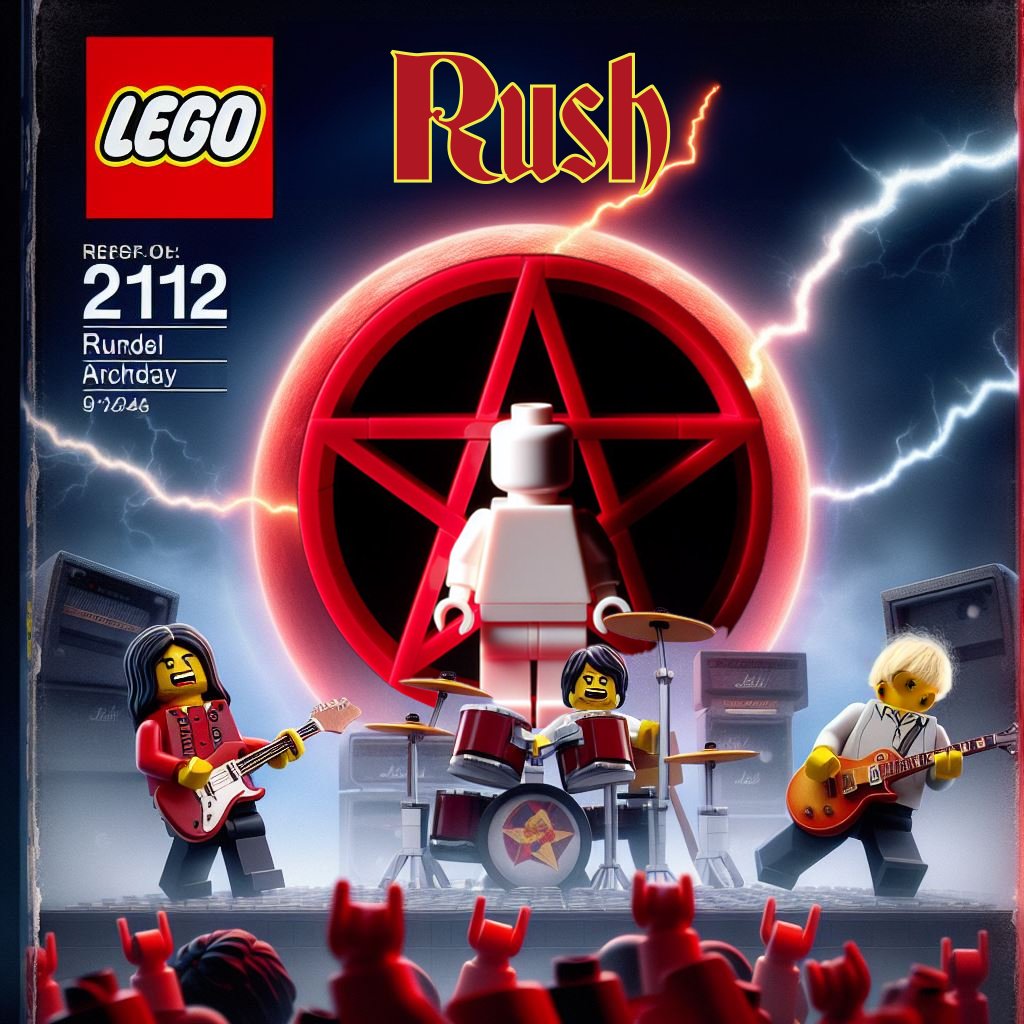

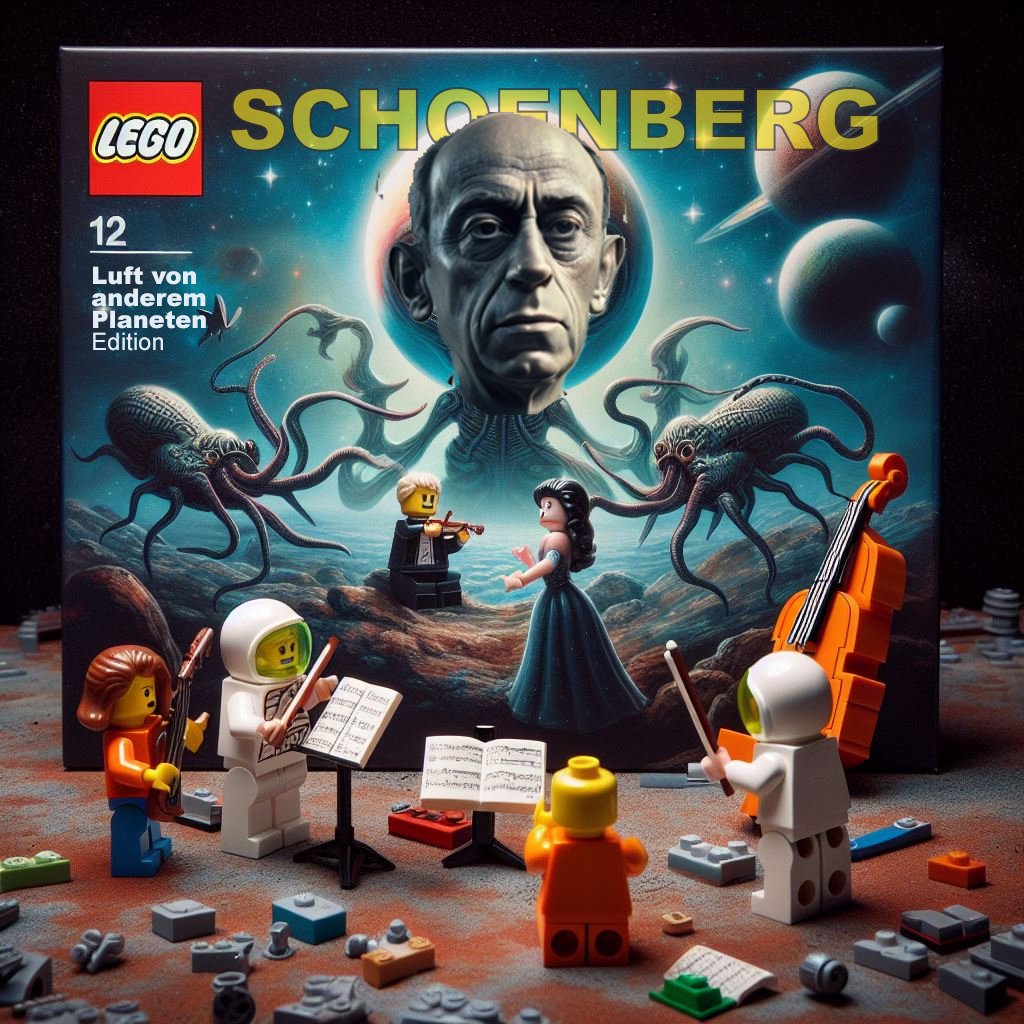

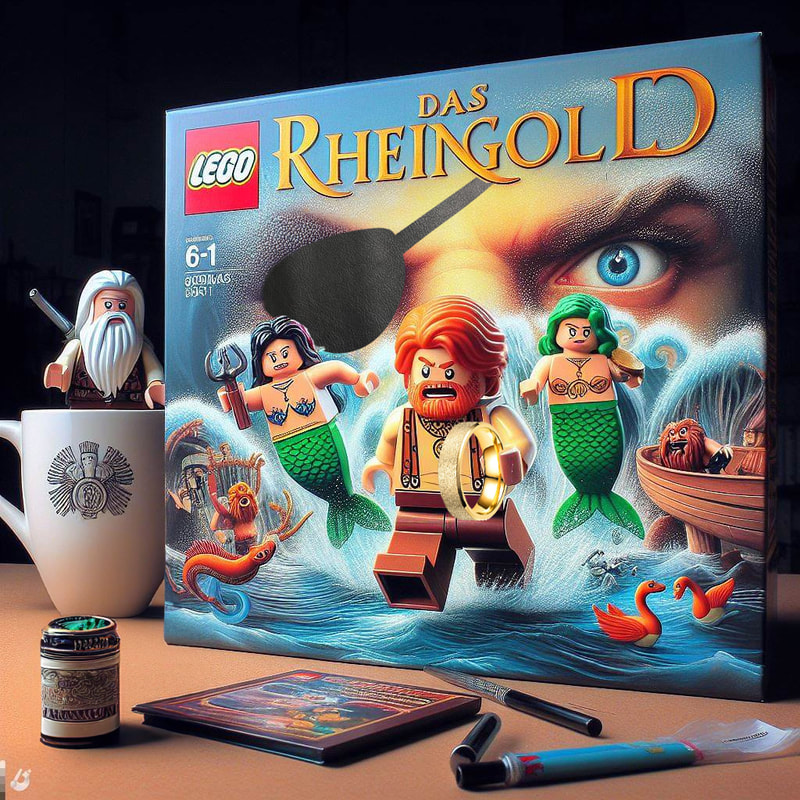

Music evokes images. A record comes with a cover. To listen to an opera is to look with your ears. Music can unlock a world in the mind waiting to be made visible. And an AI-image generator can be a handy tool for that. After previously toying around with prompt design, resulting in the image gallery of Der Ring des Nibelungen in Steampunk-style, Wagner & Heavy Metal goes to Legoland. Music from my adult life staged with the toys of my early childhood. It's a versatile toy, you can make all sorts of things with it, which perhaps because of its limitation is still so popular. It's like building something in low resolution with 3D pixels where the Lego bricks, even if they only exist virtually, add a decidedly tactile dimension (indispensable in a digital world). We begin with history's first rock star, Franz Liszt, the man who reinvented the piano, a bit like Jimi Hendrix reinvented the electric guitar. A man whose concerts delighted his audiences (women!) in proto-rock-like fashion. Next: the man whom Liszt saw as the starting point for the musical innovation of the 19th century; Ludwig van Beethoven. “Beethoven’s music sets in motion the machinery of awe, of fear, of terror, of pain, and awakens that infinite yearning which is the essence of romanticism.” — E. T. A. Hoffmann Richard Wagner, as well as being a composer, was a man of the theater. When asked what images to add to that illustrative music of Wagner, Frank Castorf came up with fascinating and frustrating answers for his Ring production for Bayreuth. The result, however, stuck. Since that Ring production, the crocodile has been a visual leitmotif that automatically brings thoughts to Siegfried. Nor has the image of Wotan eating spaghetti left me since. Bayreuth is host to some of the most daring Wagner productions in the world, and Tobias Kratzer's Tannhäuser and Stefan Herheim's Parsifal are certainly amongst the most bold and successful. Productions in which the mind-boggling sound world of Wagner finds a worthy partner in the imagination of the theatermaker. Hans Neuenfels' Lohengrin production introduced me to the hallowed ground of the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth and to the often avant-garde productions of Wagner's operas that this festival stages. There I learned to appreciate the kind of stagings that take a free interpretation of the source material, even if those interpretations seems counter-intuitive. Better a production that dares to make choices than one that playes it safe. After all, for the ideal staging you always can, and especially in a Wagner opera, rely on your own mind. When I attended Lohengrin at the Festspielhaus in 2014, I felt those jitters again that I knew from my youth, those jitters when I first attended a concert of my idols Rush. I consider their album 2112 my introduction to heavy metal. There was little more heavy in those years than the title track and the priests of Syrinx. Slayer has always held a special place in heavy metal. With Slayer, no danger of metal sounding stiff. Their music, with its abrupt tempo changes and out-of-the-box (atonal!) guitar solos, creates a realm of sound that combines tightness and looseness in a way that is unique in metal - metal mayhem in which time flies by so fast it seems to stand still. It makes Slayer (with Jeff Hanneman and Dave Lombardo!) at their best moments sound more like an extension of an electric jazz band on steroids than a hard rock band. Slayer proves that in order to take your breath away, music (any music) has to breathe. With their third studio album, Reign in Blood, the band reached the top of the trash metal Mount Everest. Back to operaland where things can also get very bloody. An opera like a slasher-movie is Richard Strauss' opera Elektra from 1909. A screaming-for-vengeance opera that brought domestic relations to dystopian lows and drama in the genre of opera to new musical heights. Alban Berg's Wozzeck was the first opera I saw live. Reducing Wozzeck to atmospheric music to a tragic story does Alban Berg's musical drama a disservice (Karl Böhm called Berg a greater dramatist than Wagner) but the cinematic component in Berg's music is unmistakable. It made the first atonal opera in music history arrive at me a lot more accessible than expected. Moreover, it made me curious for more. Fortunately, there was also Lulu (Berg's other, second, opera and this guilty pleasure). After Alban Berg, it was tracing the path back to the founder of the Second Viennese School. The air of other planets in Arnold Schoenberg's second string quartet with soprano was a path to a new music and a breath of fresh air. At the end of many an opera, many a main character dies. For Tristan and Isolde, that death is a portal to a world where they can finally be together. A world beyond the perception of the senses. An opera that is like a fever dream in which you can die of undying love. In Wagner's highly visceral music lurks a staging. It is perhaps for this reason that a Wagner opera often presents itself in an ideal way in a concert performance. In Siegfried, Wagner gives free rein to the symphonist in him. Here he seems to have less consideration for the singers' audibility. In Bayreuth, that audibility is guaranteed because the orchestra is below the stage. In a concert performance, however, the singers must contend with an orchestra at full exposure. In that glorious wall of sound, coming form the ideal sound system that is the Wagnerian orchestra, a world reveals itself into which you, as a listener, love to get lost. The more you try to make something look realistic, the more you see that it is fake. To be appealing and believable, a certain degree of abstraction is indispensable. Wagner was notoriously unhappy with the 'natural' staging of the first Ring production in Bayreuth in 1876 (the only production he saw in his life, except in Bayreuth also in Berlin at Angelo Neumann's Ring-on-tour). He let it be known after that premiere that next time it would all have to be different. How it should be done then was an answer that remained unanswered at the time of his death. We now know that definitive answers to the staging questions posed by the Ring do not exist, nor is it desirable to look for them. We conclude with a more or less 'traditional' design of the Ring operas, after all that Regietheater, with ample room for the fantasy element. Software: Microsoft Bing, Adobe Photoshop

- Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

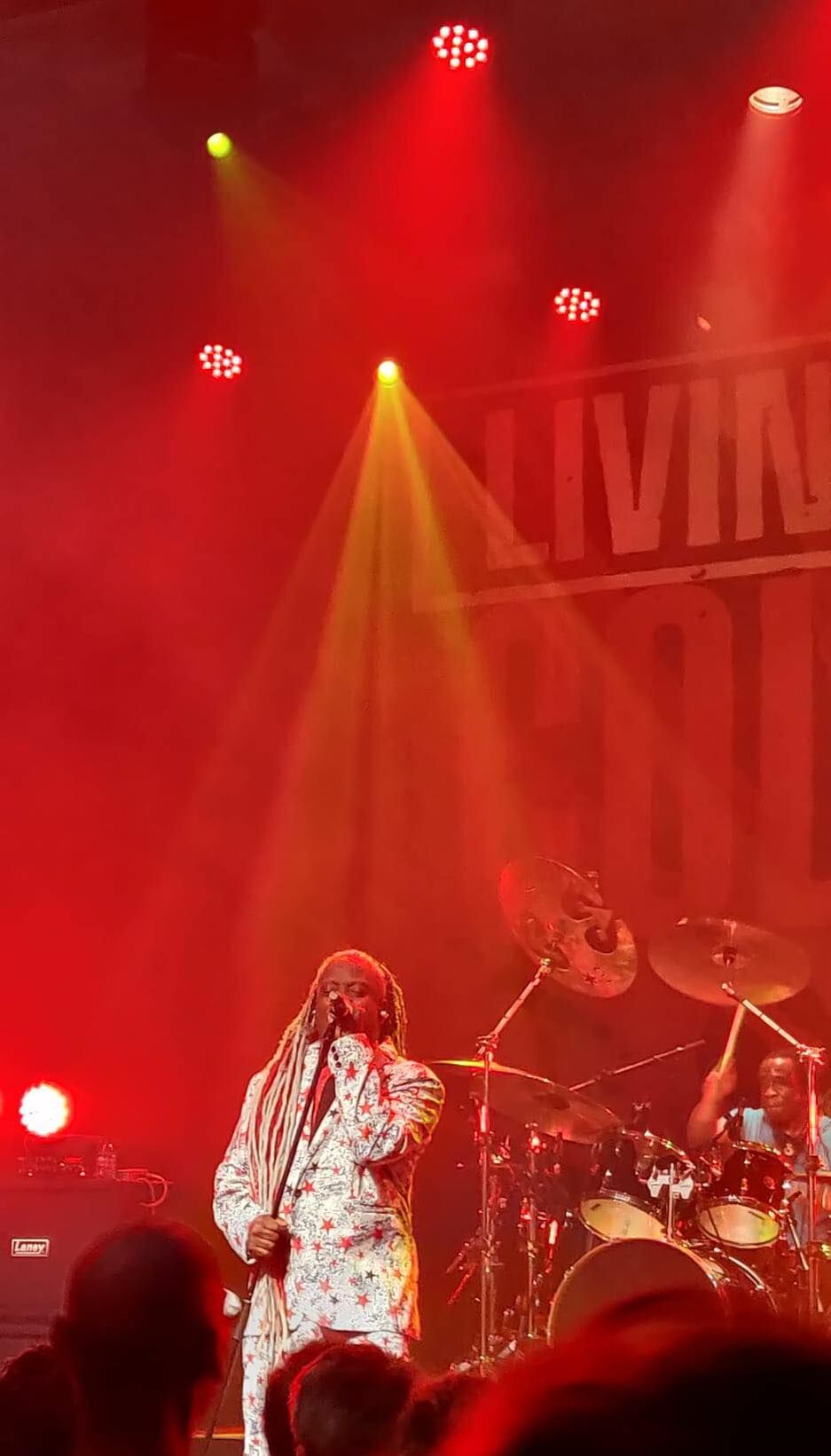

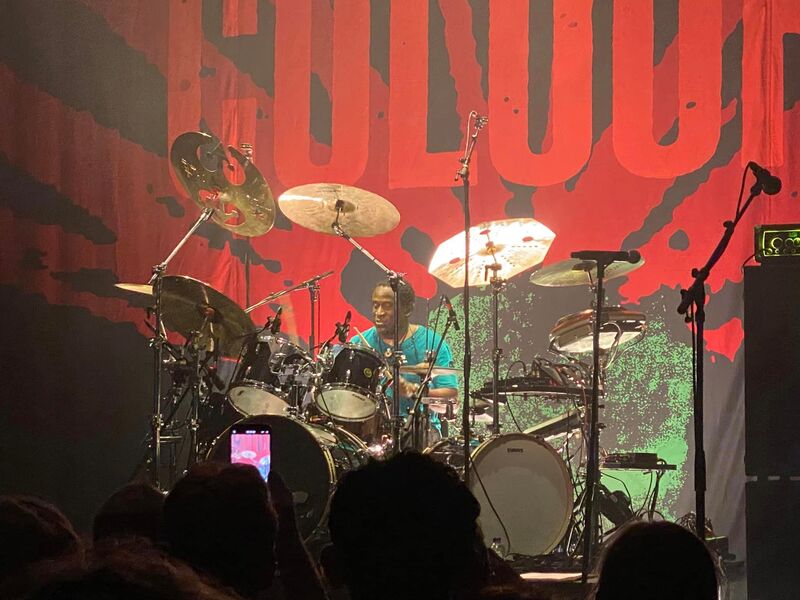

Time's never up for the hard-edged and multicoloured metal of LIVING COLOUR. After more than three decades in the business the New York-quartet still enchants the senses with craftsmanship & passion. The 1980s were drawing to a close. The decade in which bands like Rush and Metallica did deliver their best work, but also the decade in which pop music largely lost me as a listener. The sound of the 1980s was the sound of music in a blister pack. Music whose kitsch stuck so nasty to the eardrums that the sound of names like Spandau Ballet and Cock Robin make the hairs stand up straight in the back of my neck to this day. It would not be until 1991 that Nirvana, with Smells Like Teen Spirit, would give the final blow to the plastic pop sound of the previous decade (and for that alone, Kurt Cobain deserves a statue). A few years earlier, in 1988, Living Colour had shed light in those sonically dark times of celestial mediocrity with their debut Vivid. The record was a storm of fresh air that blew open the door of the (then) white bastion of rock music. A record that would make mixing genres hip and was part of a movement that I will conveniently call funk rock. I started fishing in a pool in which bands like Fishbone, 24-7 Spyz, Red Hot Chili Peppers and Faith No More were swimming. Living Colour made music that confirmed what you actually already knew, that genre boundaries don't really matter that much. Living Colour not only rocked hard, they also, as is often the case with good music, made you curious about where their music came from. Through Living Colour, I followed the path back to bands like Bad Brains and Funkadelic. Bands that were like the missing link between Jimi Hendrix and the hard rock of that era I was listening to. Living Colour complemented your knowledge and expanded the mind. I kind of lost track of them after their third record Stain. A gig, as part of the European leg of the Stain 30th Anniversary tour, was a re-encounter with the heroes of my youth. It was an utter pleasant and insistent reminder of what a beast of an album Stain was, and what a powerhouse of a band Living Colour still is. It lasted two songs. It took band and sound a bit to find each other, but once the quartet embarked on an integral performance of their album Stain, it was all hit and no miss. Go away, opening track from that record, with a riff from the meat grinder, set the tone for a party in multicoloured sound. Forged with metal that splits skulls -spiced with punk, funk, soul, hip-hop, trip-hop and jazz- they enchanted the senses with passion, craftsmanship and elegance. Living Colour was never a band that resorted to mere platitudes and simple tricks to make their music accessible and engaging. Instrumentation and vocals do not follow each other in obvious ways. No melody over a chord progression played with just barre chords. Beneath those ever-lyrical vocal lines lies a volcano of harmonically and rhythmically challenging instrumentation that sizzles and boils. The exceptional musicianship of the quartet from New York has always guaranteed dazzling live performances but at this gig the band sounded exceptionally inspired. "Never take a sold-out venue for granted," Vernon Reid had tweeted prior, and that thought and feeling translated into a performance that did what good live performances do. It purified and it liberated body and mind. That the music has more than just stood the test of time was no surprise - we took note of it with exhilaration and delight. Frantically singing along to songs until your head is loose on your neck is sometimes what a person needs on a Friday night at the end of the week. That that person, in politically shaky times, feels a song like Ignorance is Bliss closing in on him and notes that the band's lyrics are as relevant today as they were three decades ago was an experience that was not undividedly liberating. Times don't necessarily change for the better and, like three decades ago, Time's Up. Still. The riffs coming from the guitar of Vernon Reid were like insights cleaving the mind, with his solos exploring the territory from James Blood Ulmer back to John Coltrane - tapestries of notes manifesting into sheets of sound. Sound eruptions that created a sense of freedom, an energy of anything goes, something one finds, for example, in artists as diverse as Prince in his best guitar solo moments, as well as Slayer's Kerry King. The undulations in Corey Clover's voice were by turns like a caress of the evening wind and a scream from the underworld. Doug Wimbish took a moment to celebrate the anniversary of half a century of hip-hop. Wimbish was on fire. This time no fiddling with a laptop, thankfully, but full focus on inspired bass playing that, in a choreography of flowing movements and driving power, smashed its low notes like graceful splotches of paint on a colourful canvas.

LIVING COLOUR, Gebouw-T, Bergen op Zoom, 8 December 2023 - Wouter de Moor

|

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed