The knight of the Swan in a world of Swasti-swans and war. Opera Vlaanderen starts the new season with David Alden's take on Lohengrin. Opera Vlaanderen starts the new season with Lohengrin, in a regie by David Alden. A production that played this summer at the Royal Opera House in London. With performances in Ghent and Antwerp, one could say that Lohengrin, which story is set in Antwerp, comes home. Lohengrin is perhaps Wagner's most lyrical opera, written at a time when the man busied himself with revolutionary activities (up to the Dresder revolution of 1849). Activities that forced him to move to Switzerland. It was not sooner than 11 years after its premiere in 1850 in Weimar (conducted by Franz Liszt) that he would be able to attend a full performance of Lohengrin. With Lohengrin, Wagner took a formidable musical step towards to the Gesamtkunstwerk he had in mind, a work of art in which all disciplines; text, music and theatre are an equal part of the final result. This Gesamtkunstwerk would ultimately not take shape according to initial thought. For that the power of music was simply too great, the ability of music to elevate the mind, to achieve transcendence, too unique. Listen to Lohengrin, with Italian and French Grand Opera in mind, and you will get a sense of the giant leap Wagner is taking towards an opera form that seamlessly integrates the chorusses, recitatives and arias into a music drama that flows and doesn't falter. The choir scenes and the individual arias are not so much climaxes here, no points of arrival, but always new points of departure. In Lohengrin, Wagner strings together, for the first time, his music drama along an Unendliche Melodie. The story of Lohengrin can be seen as a parable about saviors and strong men. The historically sensitive "looking for a strong man in the German Empire" premise results in a staging that refers to war violence and Nazis. David Alden places the fairy tale-like Lohengrin in a raw, realistic world. Although the Leni Reifenstahl-like stage images don't leave the viewer any doubt about their origin and character, their use remain abstract enough not to nail the piece solely to the Nazi-era. Both scenery and singers/actors show traces of war violence. A city that has fallen to ruins and in which the sirens of the air raid are prominently present. In search of soldiers for his army to face the (alleged) military threat from the east, King Heinrich finds in Brabant a part of his Empire that is in severe decline. The recruitment of soldiers is a violent matter, Heinrich does not rely on the power of argument, he does not assume that those who have to serve as cannon fodder voluntarily will sign. Heinrich knows, and the stage imagery suggests so, that the people are tired of war as many of them show traces of recent violence. It puts the nine years of peace mentioned by Heinrich when he makes his entrance, in an ironic (call it sarcastic) frame. It's part of a message, addressed to the people of Brabant that should remind them to be grateful for all what the king has done for them. A message that solidifies the debt the people have to their king and that they should not complain about the fact that the king is now asking something (only their life) in return. The war scenery and Nazi symbolism places the story of Lohengrin in a dark world. A world that magnifies the contrast between Lohengrin, a grail knight, and the deplorable state of the people who ask him for help. A world that underlines the distant journey of Parsifal's son, who comes from a fairy tale kind of world, to the world of mankind, only to have his share of earthly love. Nothing as human as a demigod. His love for Elsa is not meant to last. The relation between Lohengrin and Elsa is one of great inequality. A covenant between a demigod who asks for unconditional love but whose name must remain hidden for those who love him. It puts an impossible burden on the mind of Elsa (encouraged by the intrigues of Ortrud and Telramund) who has to ignore her curiosity. A class in art history might have saved Elsa a lot of misery. On the wedding night, at the beginning of the third act, we see in the bedroom the famous painting of Lohengrin by August von Heckel. Elsa looks at it as if she is trying to recall its title. In vain. So she asks Lohengrin the forbidden question, she bites into the forbidden apple. Grail knights and questions, they go back a long way. In Chrétien de Troyes' original version of Perceval, the title hero, Lohengrin's father, forgets to ask his host, the Fisher King, who serves the grail. It is the question that would have healed the wound of the king. In Lohengrin the forbidden question, in text and leitmotif, hangs above the opera like a sword of Damocles. The fall of that sword is inevitable. When it does Elsa loses her hero and husband, Telramund loses his life (he is killed by Lohengrin when he violently enters the bedroom by breaking through the wall) and the king loses his strong man. As King Heinrich, Wilhelm Schwinghammer took over the role of the Thorsten Grümbel (who was ill) and did so with great acclaim. Schwinghammer portrayed Heinrich not without humour and turned the king, eventually, into a deeply tragic figure. Schwinghammer was a last-minute addition to the cast (at the premiere he sang the role from the side of the stage while the sick Grümbel played the role onstage) of which Liene Kinča and Iréne Theorin made their roll debut as respectively Elsa and Ortrud . Kinča's voice sounded as if it was trapped in a small room. This was not a problem in the quiet belcanto parts of the role (she was a sensitive, beautiful Elsa) but with the high notes she pushed her voice over the edge. Her savior Zoran Todorovich had some problems in the role of Lohengrin. He had clearly paid extra attention to his "In Fernem Land" but there were some pale colours on his vocal palette. As a direct consequence of this, the role left much to be desired and it showed the power of the Wagner drama and of this production that the piece eventually managed to make such a convincing impression. They ultimately bite the dust, the bad guys in this story, but from an artistic point of view, Iréne Theorin in the role of Ortrud and Craig Colclough in the role of Telramund were the real winners of this performance. Theorin's debut role was convincing in every respect; she was portrayed as a kind of secretary, an iron lady whose job, doing the administration, merely coverted that she was the one who was pushing the buttons. As Telramund, Colclough delivered perhaps the best role of the performance. Falling from grace and banned after his defeat by Lohengrin, Colclough epitomized the tragedy of Telramund in an intrusive way. The strenght that Colclough's Telramund displayed was made of superb theatrical make-belief. His strenght was the mask of a con man. As a step-father of Elsa, Telramund was not strong enough to resist Ortrud's evil intentions and he went as far as indicting his own stepdaughter. The child must have had a traumatic childhood. This production doesn't try to bend the story in a more sympathetic outcome (like this year's "feminist" Bayreuther Lohengrin). This visually impressive Lohengrin ends in tragedy for all those concerned. The only winner seems to be Gottfried, Elsa's supposedly dead brother, who, alluding to the future in the final stage image, presents himself as the new strong man the people so vehemently long for. It is an image that bears in it, perhaps more than the Nazi symbolism, the true warning of this Lohengrin. That totalitarian tendencies do not begin with a strong man but with the longing of the common man for that strong man. Opera Vlaanderen - 23 September 2018 Dates: Ghent: Th 20, Su 23, We 26, Fr 28 September Antwerp: Su 7, We 10, Su 14, We 17, Sa 20, Te 23 October Conductor Alejo Pérez Regie David Alden Decor Paul Steinberg Costums Gideon Davey Light Adam Silverman König Heinrich Wilhelm Schwinghammer Lohengrin Zoran Todorovich Elsa von Brabant Liene Kinča Telramund Craig Colclough Ortrud Iréne Theorin Heerrufer Vincenzo Neri - Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

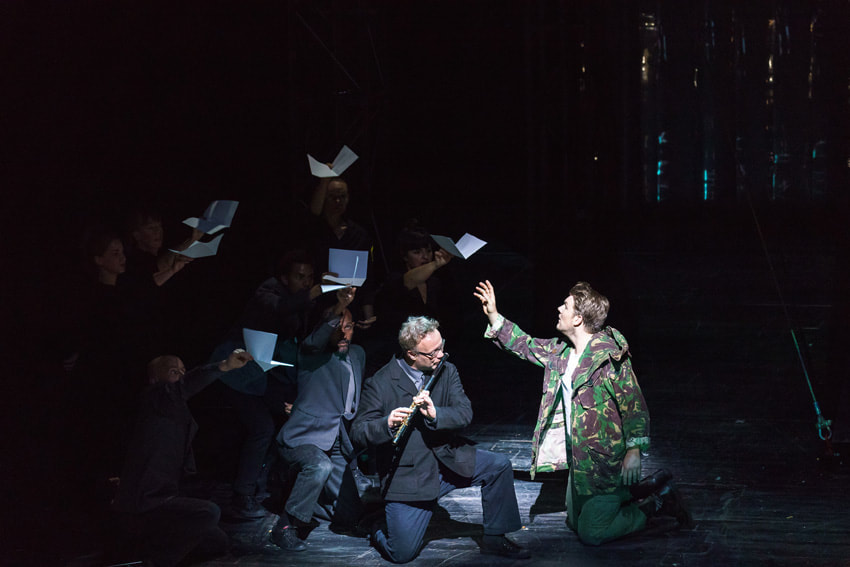

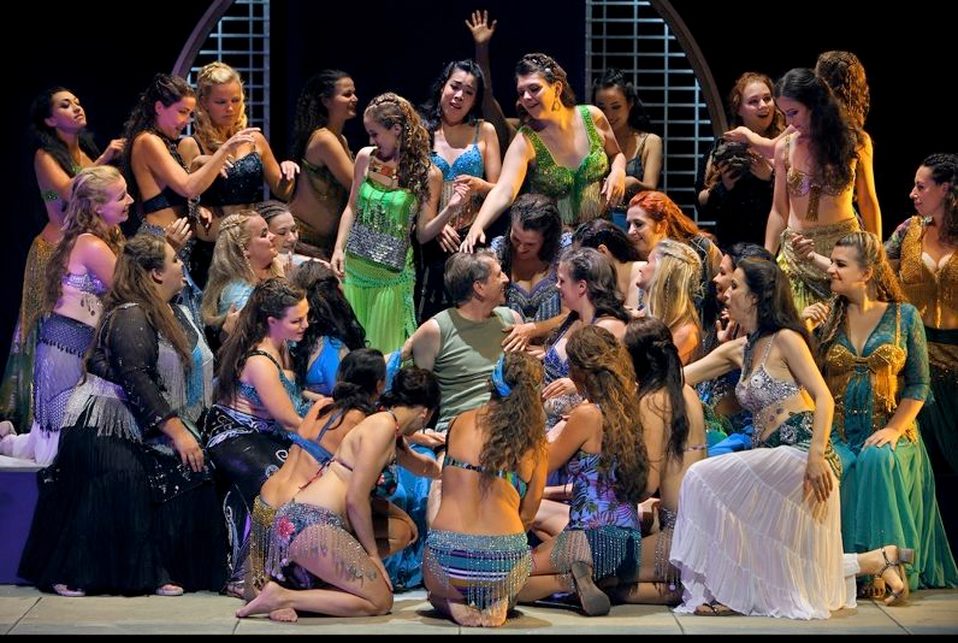

Simon McBurney's production is a roller coaster that revamps the magic in Mozart's Die Zauberflöte The Dutch National Opera kicks off the new season with a production that has proved to be succesful at the Amsterdam Muziektheater before. It was an instant hit at the 2012 premiere, received a lot of acclaim in London (at the English National Opera), the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence and was already endowed with a DVD release. Now, six years later, Simon McBurley's production didn't lose anything of its impact and power to attrack a new audience to Die Zauberflöte. Simon McBurney, who already astonished us with his production for Alexander Raskatov's 'A Dog's Heart' (the collaboration between theatre man McBurney and composer Raskatov yielded theatre of a rare level, there will be few productions in which opera and staging have found each other so seamlessly), confronts Die Zauberflöte with his seemingly childlike curiosity. His initial unfamiliarity with the opera, bordering on aversion (what is h*ll is this piece actually about?) results in a production in which McBurney shares with us, the audience, in an irresistible way, his own amazement about the sometimes inimitable scenes and storylines. With a lot of inventiveness he shines light in the sometimes muddy world of The Magic Flute and does not forget that Mozart's opera, commissioned by Schikaneder, is besides an important piece in music history, above all an excellent piece of entertainment. It was Mozart's almost-last opera (after this he would only be able to get the rush job La Clemenza di Tito done) in which Salzburg's most famous son explored the boundaries of the genre and, to quote Richard Wagner, delivered the first real German opera. An opera that would, by its innovative concept, inspire Carl Maria von Weber for Der Freischütz and Oberon (the source material for Die Zauberflöte came from a collection of oriental fairy tales by Christoph Martin Wielands, the author who wrote the heroic poem Oberon). Die Zauberflöte, opera or Singspiel, with its many dialogues, its leaps and bounds between seriousness and jollity, can sometimes give the impression of patchwork. A conglomerate of too much ideas in which the final result does not always exceed the sum of the individual parts. A theatrical layer of sufficient substance is necessary to make the music and the spoken word into a convincing whole. McBurney connects the spoken word to inventive action with finds that are as simple as they are brilliant (for example, the birds that fly around Papageno are simple sheets of white paper in the hands of actors that make fluttering movements with them) and keeps the pace of the action high. There are video projections (they provide a very beautiful fire and water trail) and decorations with a keen eye for contrast (the Drei Knaben with their lovely voices look like they come straight out of a horror movie). Everything about the production breathes freedom and displays a virtuoso handling of the source material (with humour that is really funny and not bland). In addition, the playground for the singers/actors is not limited to the stage. Especially Papageno, a fantastic role of Thomas Oliemans, reaches in the role of the bird catching bohemian literally the audience beyond the front rows. All involved, both singers and musicians, have an active part in the acting part. For playing the flute Tamino (Stanislas de Barbeyrac) calls upon the flutist in the orchestra pit (no shaky mime act here) and conductor Antonello Manacorda (who spend his time between this production in Amsterdam and Romeo Castelucci's production of Die Zauberflöte in Brussels) not only indicates the entries and the tempo of the music but also shows his (feigned) horror about Papageno's clumsy (and hilarious) behaviour. In his search for the heart of Die Zauberflöte, for what the opera actually is and what it stands for, McBurney takes the opera far away from the realm of child operas and stiff productions that the catalogue of the Magic Flute is so lavishly filled with. It results in a night at the opera that is like a fantastic voyage in which many (read: yours truly) are exposed, for the first time, to the theatrical beauty of the piece. A performance in which a few side notes that can be made about the vocal performances are no more than just that, minor details in a terrific whole (the voices of the three ladies who save Tamino from the dragon could have harmonized a bit more beautiful with each other and the bass of Dmitry Ivaschenko (Sarastro) lacked some definition in the lower regions of the singing parts). Die Zauberflöte is an opera about the battle between good and evil, between light and darkness, with strong references to the Freemasonry, the fraternal order from which Mozart and librettist Schikaneder both were members. A group, led by Sarastro here, that abducts children to evade the unreasonable and hysterical influence of their mother. Reason and science show themselves a bit unreasonable and harsh (it's waiting for a production in which Sarastro's temple order is portrayed as the Church of Scientology). The Queen of the Night is here a fragile old woman. She moves with a cane and sings her famous aria with breakneck coloratura and high F's in a wheelchair. She represents evil and Sarastro, in contrast to Tito, the title hero from the other 'last' Mozart opera, does not grant her forgiveness. This forgiveness still befalls her by the way Pamina (a sensitive role of Mari Eriksmoen) caresses her at the end. It is a human end of an opera in which black and white both become a bit greyer. A production in which Monostatos (a creepy Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke) is white and the references in the text to his dark skin have disappeared. Not gone are the sexist, misogynistic parts in the libretto that - even for someone who does not advocate a sanitized version of Emanuel Schikaneder's libretto - are hard to ignore. Although the stereotypical portrayal of the reasonable man and the mentally unstable woman is more laughable than that it fuels the indignation (the knowledge that the patriarchal views that fed those lyrics are far from gone prevents an all too hilarious response however). With Die Zauberflöte, McBurney delivers once again a staging that gives an incredible added value to an opera that, as an audio-only document, is mainly enjoyable when the dialogues have been seriously cut. In that respect, his Zauberflöte may well be considered a Gesamtkunstwerk in the true sense of the word. A performance in which music, text and theatre are all an equal part of the final result. A theatre experience that makes one curious for more and that makes one hope (this is after all the Wagner-Heavy Metal website) that Simon McBurney will venture into a Wagner opera in the not too distant future. Dutch National Opera 14 September 2018 Dates 7 September untill 29 September 2018 Conductor: Antonello Manacorda Netherlands Chamber Orchestra Stage director: Simon McBurney Decor: Michael Levine Sarastro: Dmitry Ivaschenko Tamino: Stanislas de Barbeyrac Pamina: Mari Eriksmoen Papageno: Thomas Oliemans Der Sprecher: Maarten Koningsberger Königin der Nacht: Nina Minasyan Ein altes Weib (Papagena): Lilian Farahani Monostatos: Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke - Wouter de Moor

Laufenberg's production is a bit of a bumpy ride but Parsifal in Bayreuth is an experience like few other opera-experiences ...

Click on the image to read on >> |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed