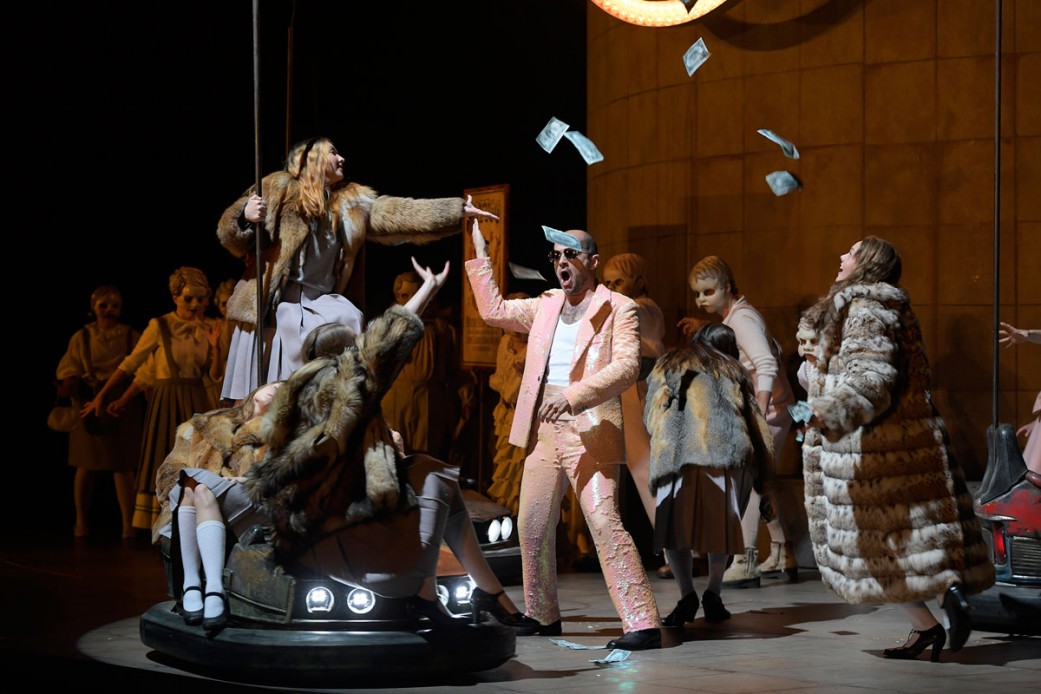

A trip to Berlin. To the heart of the German (and European) canon with Gounod's Faust at Deutsche Oper. Berlin is a city with more history than might be good for a city. A city where the past weighs heavily on streetscape and conscience (Vergangenheitsbewältigung is a German word) but where the craters of world war bombs and communist demolition turn out to be a fertile soil for an unprecedented rich cultural life. Berlin, a city with many theatres, including three opera houses, with its different quarters, each with its own character and dynamics, is like a city that consists of many cities. My return to it, after a five-day visit, will only be a matter of time. 3 ... My visit started in the outskirts of the German capital. In Potsdam, where I attended a three hour Baroque opera: L' Europe Galante from André Campra. Four scenes about love, with accompanying heartbreak, situated in four different countries: France, Italy, Spain and Turkey. The 1697 opera-ballet was brought to the stage by the musicians, singers and dancers of Les Folies Françoises & Collegium Marianum Prague with passion and a great sense of theatre. An energetic performance that could not conceal the fact that Campra's music remained fairly uniform in all four parts. Add to this the fact that there was little or no dramatic arch and the decades that separate the piece from Gluck and Mozart (from operas with characters that are delicately refined by music and libretto) looked upon us, straight into our opera-loving faces. It was the subject that gave L' Europe Galante a topical touch, but further searching for extra layers or transcending thoughts proved futile. More than 300 years ago this singing and dancing piece served to entertain the aristocracy, a way to make it through a Sunday afternoon, and more than mundane entertainment for a, in this case, beautiful summer evening in Orangery Palace Sanssouci, it wasn't now either. ... 2 ... I continued my journey to the city where I visited - after the inevitable Frank Castorf deja-vu on Alexanderplatz and an excursion to the Dussman KulturKaufhaus where I once bought my first complete Ring des Nibelungen (Clemens Krauss & Karl Böhm in 1 purchase) - the Deutsche Oper Berlin. Here I attended Faust of Charles Gounod. In Goethe's version, Faust is a rustproof part of the German canon. Performed as a French Grand Opera on Berlin soil with upper titles in German and English, it could serve as an example of, as well as a pledge for, European integration. .. 1 Faust is a story about guilt, punishment and time. Time that, for ordinary mortals, is irreversible and almost always too short. (With the sudden death of Vinnie Paul - drummer of knuckle-sandwich-metal band Pantera - a few days earlier as a grim reminder of this.) To escape time and decay, a man in a late-life crisis sells his soul to the devil. In return he gets the body of his youth back and with it Marguerite. Director Philipp Stölzl places Marguerite at the heart of the story. We see the story unfold like a flashback from the women's prison where Marguerite, convicted for the murder of her baby, awaits her execution. We see the story pass us by, literally, against the backdrop of a large tower around which a plateau is turning. A rotating platform that provides scene changes with an open curtain. Faust exchanges the wheelchair in which he sits at the beginning for a bumby car from a fancy fair, his hospital clothes for those of a party animal, or pimp. He exchanges the prison of old age for the carnival of life and joins the party that Méphistophélès throws. He takes advantage of Marguerite only to leave her. In spite of everything, Marguerite continues to believe in his return and good intentions, but eventually kills her child in a nervous breakdown. More than guilty of murder, Stölzl sees Marguerite as a victim of circumstances and her ill-minded fellow human beings. People that hide their individuality, and lack of compassion, behind fish masks. A direct reference to the 'Fishfolk' from a poem by Bertold Brecht, about the German people in Nazi times. ACTION ! Philipp Stölzl is a film director - with Nordwand he introduced me to an unknown piece of German mountain climbing history - who explicitly seeks cinematic effects in this 19th century music drama. We see a use of slow motion from people who, eventually, freeze into mannequins, we see dolls in rotating tableau vivants. It produces beautiful images, but the tower and the rotating platform reduce the staging to a somewhat static whole as the opera progresses. It seems as if towards the end the direction has run out of ideas and with the repeatingly turning of the stage, the mise-en-scene has come to a standstill. A point of criticism also concerns the Personenregie that delivers some uncomfortable moments. Moments at which music and libretto try to connect in vain with the action on stage. When the women of Méphistophélès, a kind of Dracula's brides, attack Marguerite's brother, Valentin, the latter seems more interested in maintaining the hollow gesture of a Jesus Christ Pose than in defending himself. It is such a moment that the action is thwarted by symbolism. Perhaps explainable but a poor attempt to make action, text and music synchronize. The result is pretty stiff. ... AND CUT! Stölzl makes significant cuts in Gounod's opera, reduces it from five to four acts and takes out the ballet of the Walpurgis Night because it would serve the convention of the Grand Opera more than it would serve narrative purposes. A defensible choice that works well for this production. But also after these interventions it remains the case that the opera, after a smooth start with arias that serve the story, shifts to a story that is used to serve beautiful arias. Something in which this Wagnerian ears seem to hear some gratuitous vanity. It was the week of doppelgangers. Just like in Prokofiev's The Gambler a week earlier in Ghent, here too the main character looks back and sees itself as another person. Marguerite sees herself as a girl, with balloon and hammock chair emphasizing her innocence at the moment that Faust violates her. With this depiction of Marguerite as a child, the initial unscrupulousness of Faust, driven by carnal lusts, encouraged by Méphistophélès, is all the more inciting, and the contrast with the moment when Faust discovers that it is love what he really wants becomes only larger. Regret does not release Faust of his sins. His attempt to liberate Marguerite fails, she rejects the possibility to escape and Faust is left behind. He doesn't get redemption because the opera stops where the first book of Goethe's Faust ends. (Forgiveness for his sins and reunification with Marguerite - at the end of the second book - are not granted to Faust here. For the opera version of that we have to go to Boito's Mephistopheles.) Marguerite dies guided by a choir of angles. A singing to make clear that she is redeemed in death. Although the latter is questionable. The angelic singing that reflects salvation can also be interpreted as something that only sounds in Marguerite's head, like a final convulsion, a glance into the tunnel with light on the other end. It is an interpretation that is in line with the fact that Goethe was not a Christian but rather a freethinker who did not want his mind to be framed by religious dogmas. Philipp Stölzl focuses on the role of Marguerite and it is Nicole Car who does justice to the fate of the unfortunate maid. In Car's interpretation Marguerite's desire and suffering become a balm for the soul. Charles Castronovo is fine as Faust, both in voice and appearance, it is a role that is a personal favorite of his. Siebel, Marguerite's would-be lover, levels with his subject of admiration when it comes to sadness. It is a trouser role, a woman playing a men's role, beautifully and sensitively sung by mezzo soprano Vasilisa Berzhanskaya. Amidst this parade of characters who suffer to a greater or lesser extent from sadness, it is the villain who eventually is the most fun. In this, Grand Opera does not differ from, say, Star Wars and Italian bass-baritone Alex Esposito seems to understand this very well. He has visible joy in his role as Méphistophélès and does the work of the devil with the contagiousness of the mischief of a boy. The opera of Gounod, who got acquainted with Goethe's Faust in French (the man did not speak one word German), is given a staging in which the Grand Opera has to subordinate to the narrative. It results in a slimmed-down Faust, call it austere (the Walpurgis Night ballet will be missed by those who see theatrical excess as a source of entertainment rather than distraction). It is a Faust that, in its economic use of resources, still does justice to Gounod while it explicitly points to the source material: the poem, and its writer, on which Gounod based his opera. Deutsche Oper Berlin, 26 June 2018 Dates: 23 June - 6 July 2018 Conductor: Jacques Lacombe Orchester der Deutschen Oper Berlin Chor der Deutschen Oper Berlin Director: Philipp Stölzl Co-Regie: Mara Kurotschka Design: Philipp Stölzl & Heike Vollmer Faust: Charles Castronovo Méphistophélès: Alex Esposito Marguerite: Nicole Car Valentin: Thomas Lehman Siebel: Vasilisa Berzhanskaya - Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

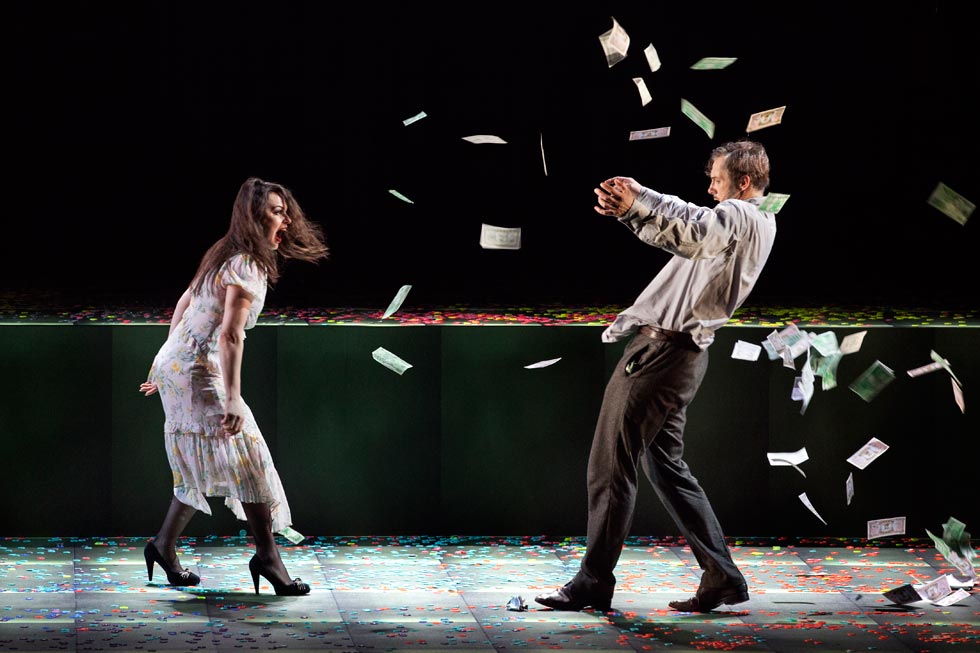

Karin Henkel turns Prokofiev's opera "The Gambler" into an ingenious piece of music theater Epilepsy, a gambling addiction and a murderous deadline. Just a selection from the list of ailments and circumstances that surrounded the conception of Fyodor Dostoyevsky's The Gambler. Lack of money and a resulting strangulation contract with a publisher (he would lose the rights of all of his works when he wouldn't meet the deadline) forced Dostoyevsky to write a novel within four weeks. Drawing on his own experience as a gambling addict, he wrote The Gambler, a story about a man who looks back on his own downfall. In 1915 Sergej Prokofiev started to write an opera, based on this story of Dostoyevsky. He took out the retrospective view and told the story in the present time. For her production for Opera Vlaanderen of The Gambler, director Karin Henkel brings back the flashback of the novel. It is her first opera production but her third production concerning a piece of Dostoyevsky. In a clever staging she shows her affinity with the writer and his talent to put moral decay and dormant lunacy in a gripping narrative. In addition to the perspective of hindsight, Henkel provides the main character, Aleksej, with a double. It is with him that the opera begins. Aleksej, or rather his doppelganger, wakes up in a hotel and tries to recollect the last eight months of his life. He tries to reconstruct his own deterioration - hoping to see something, if only a glimpse, of his real self in all those memories. Aleksej's doppelganger is played by dancer Miguel do Vale who is, from a narrative point of view, the real protagonist of this story. An opera with a dancer in the lead. A dancer who physically responds to the story that he sees passing by in his memory. Karin Henkel, together with set designer Muriel Gerstner, let the story take place on a stage that consists of three levels. Three levels within which we see present, past, reality and dream depicted without sharp distinction. It's a deliberately chaotic whole in which Henkel, with great dramatic and comical effect, shows the decay of Aleksej and the moral deprivation of the people around him. In composing The Gambler, Prokofiev was largely inspired by Modest Mussorgsky and his opera "The Marriage". An opera in which Mussorgsky took the rhythm of spoken word as a guiding principle for the writing of the vocal lines. He thus came to an opera consisting solely from recitatives: an "Opera Dialogue". In The Gambler, speech simulation - a musical translation of voice proxies, something that would in Janacek's operas reach a certain zenith - and martellato, a hammering staccato, results in a piece of music theatre that is filmish rather than it is operatic. One will look in vain for an aria - or a beautiful melody in the sung text (the lover of Italian opera has been warned). The arioso recitativo of the dialogues, which are largely copied 1-on-1 from Dostoyevsky's novel, are almost continuously agitated in character. The aspect of contemplation of Dostojevski's novel is a bit left to it. In interludes with spoken texts, coming from the novel, Henkel gives Prokofiev's opera some relief. She grants us a few moments in which we are given a more intimate look into the inner world of Aleksej.  © Opera Vlaanderen © Opera Vlaanderen The Sprechstimme and Sprechgesang in, let's say, Wozzeck, don't stop that opera from making an emotional impact and although The Gambler certainly makes its mark, it's the Russian-kind of Sprechgesang together with the language that keeps the story, for me, at a certain distance. The question rises whether a text-based opera like The Gambler would benefit from a translation in, for instance, English. That one, rather than listening to sounds that doesn't make it into meaningful words, gets a better grasp of the finesse of the speech simulation when one hears it in a language that one is, more or less, familiair with. That the idea that lies behind this way of writing vocal lines becomes more eminent, literally more meaningful, and results, eventually, in a performance that is, in the end, a more engaging one. (As the English translation of "The Makropulos Case" did. That recording of an ENO-production did shed some light in Janacek for me.) In an opera that doesn't dwell on beautiful arias, with music that is more orientated on action than melody, the acting of the singers is, even more than usual, as important as their singing. Ladislav Elgr as Aleksej and Anna Nechaeva as Polina perform that task, together with the rest of the cast, more than adequately. But it is Dostoyevsky-expert Karin Henkel - with an ingenious staging in which she does justice to both Prokofiev's musical wit and sarcasm as well the stratification of Dostojevski's novel - who is the real star of the evening. Opera Vlaanderen 17 June 2018 Dates: 13 June until 7 July 2018 Conductor: Dmitri Jurowski Regie: Karin Henkel Decor: Muriel Gerstner Polina: Anna Nechaeva Aleksej: Ladislav Elgr The General: Eric Halfvarson Babulenka: Renée Morloc The Marquis: Michael J. Scott Blanche: Kai Rüütel - Wouter de Moor

RING OF CANTATAS This year's BachFest featured something special. A Ring of Cantatas, sung in Thomaskirche and Nicolaikirche. Under the baton of John Eliot Gardener, Ton Koopman, Hans-Christoph Rademann and Masaaki Suzuki - conductors with a complete recording of Bach's cantatas (the ones that survived ink corrosion, flames and other mischief) under their belt - a rarely seen (and heard) series of concerts were given in which 33 of the best cantatas (and yes this is subjective) were played within a 48 hours timespan. Contractual obligations refrained Bach from composing operas. The cantor of Thomaskiche was not supposed to occupy himself with such worldy matters. But changing times and the accompanying relaxation in the relationship with religious heritage have brought Bach to the opera house after all. JOHANNES PASSION For me BachFest started with Johannes Passion, a 2017-production of Opera Leipzig, in which Bach's most dramatic of passions was paired with modern dance. In a choreography of Mario Schröder, the clerical music of Bach was staged with a worldy ballet. A ballet in which Schröder did not bother, and rightfully so, to put a literary telling of Jesus' cloister on stage. What can be heard in music and text needs no doubling on stage. More than a depiction of the crucifixation, the ballet was a rendering of themes, lying beneath the story of Christ. A visualition of a story about suffering and the need for salvation. The need of humans to appoint someone savior. The ballet put the story in a world of decay. A world with a possible chance for a new beginning, awaiting at the end. Together with the theatrical and dramatic element already in the music this Johannes Passion obtained with its vividness and sensual aspect of contempary dance by times the energy of a rock opera. Jesus was not played/danced by one person but by a pair of dancers: one man and one woman. A Jesus-tango of sorts, dressed in black, as to seperate them, in image, from the rest of the dancers: the crowd and the Pharisees that would eventually come for Jesus' blood. The couple that was Jesus danced with each other, danced against each other, as to depict an inner struggle, and kept themselves at save distance from their environment. Their duet was, although not devoid from sensuality, a somewhat stylistic affair, it never reached, let's say, a Cherkaoui-kind of rapture or tempation. The couple never fully interwined as if Jesus, the supposed savior of mankind, was a broken person. A person that was looking for balance and salvation him/herself. With "Ruht Wohl", that ending of Johannes Passion that never fails to move, it started to rain. It was an ending that supplied Bach's oratorium with a stage filled with bodies, presumably dead, covered with blankets - worthy of anything this side of Götterdämmerung. A pairing of the end of the world with the resurrection of Christ. The Jesus-couple kept dancing till the end, against all odds. As if their continuing doing so would save the world, if only in mind, from perishing. Thus keeping the illusion alive that mankind was redeemed and offered a new start. In this setting, the role of musicians and singers was limited (if one can say that when Bach's music is played) to a guiding one. The musical direction was in the hands of Paul Goodwin who led the Gewandhausorchester in a swift and energetic reading of the score. Martin Pertzold was a versatile Evangelist and Alexander Knight a powerful Jesus. In comparison with her male colleagues the soprano of Magdelena Hinterdobler sounded a bit stiff, as if she wasn't performing up to her abilities. It was a performance in which the ballet was up to a difficult task: to provide Bach's oratorio with a worthy visual counterpart on stage. It worked for the better part, thanks to a choreography that left enough room for interpretation and did not bother to literary depict a story that was already very present in music and text. The undoubtedly good intentions behind the added intro - with a call to prayer from a mosque and a synagogue, as a reference to topical times with it tensions between religions - did not save that intro from falling flat on its face. It sounded like a technical error rather than a convincing start. But then, what else than the stirring Herr, unser Herrscher is a better start for the oratorio that, as it was proven here again, can serve as an excellent music drama? BACH FOR BRUNCH The next day I had Bach for brunch. Together with cantates of Heinrich Schütz (composer of the first German opera - "Dafne" in 1672 - and considered a founding father of lutheran baroque), Telemann and instrumental music of Biber, a musical brunch was served in Alte Börse. An old Exchange in the centre of Leipzig that housed a concert that was, on all counts, a heartwarming event, The heat made a repeatedly tuning of the violins necessary, sweaty as the gut strings became in these tropical circumstances. In the cantatas of Schütz, Telemann & Bach, mezzo-soprano Genevieve Tschumi sang divine melodies with gravity and beauty and delivered them with the qualities of someone who doesn't only know how to sing but - as if the cantatas were "Lieder" - also know how to act. This musical brunch was followed, later that day, by an organ concert by Johannes Lang in the Gewandhaus. A concert that was an encounter with that other famous inhabitant of Leipzig, Felix Mendelssohn. Lang delivered the sonates for organ from Bach and Mendelssohn with finesse and fury on the most majestic and theatrical of all instruments. In Mendelssohn Sonate A-Dur op. 65, the Fuga led to a frenzy in the audience. It was as if a mad professor, sitting in a high castle, turned his drift for world domination into the most frantic of heavy chromatic music.

- Wouter de Moor BachFest Leipzig: 8 - 10 June 2018 Festival dates: 8 - 17 June 2018 For BACH/BLOG see also:

Bayreuth has Wagner and Leipzig has Bach. Two cities and two composers who mark for me, among many other things, the beginning and the end of the summer of 2018. This summer starts for me at BachFest in Leipzig, a more than appropriate start, and ends, at the end of August, with Parsifal in Bayreuth. From the Cantor of Leipzig, who is perhaps the most important point of reference in Western music, to the Sorcerer of Bayreuth with his self-declared music of the future. One can regard the music of Johann Sebastian Bach as a construction kit, used by many, if not all, who came after him. (Of the composers who have not been influenced by Bach, I cannot in any case mention one.) More than 250 years after his death, Bach follows in the footsteps of time. At the festival that bears his name, an app keeps me up to date with last-minute offers, programme highlights and news I shouldn't miss. In Bach-Archive you can learn about Bach's life, his family background, his working method and the research into his manuscripts. The composer who spent the last 27 years of his life in Leipzig, buried here in the Thomaskirche - although there are doubts about the true identity of the skeleton that lies beneath the floor of the church - now belongs to everyone. (With special thanks to Felix Mendelssohn, also a resident of Leipzig, who turned Bach's music into repertoire for the concert hall in the first half of the 19th century.) His music can be heard on the market square, within easy reach of a beer and a Kalbsschnitzel, and in the opera house where his Johannes Passion is paired with contemporary dance. In his time Bach often received criticism on his music, which was supposed to be old-fashioned and unnecessarily complicated. That old-fashioned and unnecessarily complicated music has turned out to be astonishingly timeless. Whether it sounds in historically informed performances on a harpsichord by Gustav Leonardt or is shredded on the fretboard of an electric guitar by Yngwie Malmsteen. Bach's music is, a comparison with literature is unavoidable, a story that is bigger than the story itself. Widely interpretable, rich and fascinating enough to return to again and again - from the Wagnerian (Mahlerian) late-Romantic version of the St. Matthew Passion by Willem Mengelberg to the historical informed performance of the Johannes Passion by Masaaki Suzuki. It is music that has been resistant to rapidly changing trends. There is something reassuring in the fact that there are things from the past that can be rediscovered, every generation again. In a world where everything is changing, it is good that some things don't. They provide a certain grounding, as a possible threshold against alienation. Bach's music is like a massage for the brain - an encounter with someone, or something, of superior intelligence From my own first meeting with Bach's music, I remember an animated tv-series in which the Toccata & Fugue in D minor was used as soundtrack. Even before I knew the composer by name, I heard his music introducing a cartoon about the history of mankind. Once upon a time ... I was introduced to the divine notes of a Bach score and the sound of a church organ. I heard organ sounds drawing an impressive cathedral of sound. Even before I knew anything about music theory and its terminology, I got my mind enlightened by refined counterpoint. Bach's music is like a massage for the brain - an encounter with someone, or something, of superior intelligence. The art of sound in which - despite all the math that lies under Canons and Fugues - you'll always end up with the genius of the composer. For although Bach's music may be there for those who find comfort in structure, it is the brilliant spirit of Leipzig's most famous cantor that prevents his music from being reduced to a mere mathematical model in which artificial intelligence can take over a composer's job. - Wouter de Moor For BACH/BLOG see also:

On the birthday of Robert Schumann (born this day in 1810), Wagner & Heavy Metal goes on its way to Leipzig, the city where Robert Schumann, like Johann Sebastian Bach one century before him, lived and worked for some time. Many composers found themselves under the spell of the contrapuntal finesse of Bach's music and Schumann was one of them. With Schumann's second symphony, perhaps his most Bach-inspired composition, as a soundtrack in the early morning I'm heading for Leipzig, the city of Bach, Mendelssohn and BachFest. A train journey that will take more than seven hours, a travel of considerable lenght but a sign in open air compared to the three days that Bach once walked from Arnstadt to Lübeck to pay Buxtehude, his idol, a visit. Buxtehude who offered the young Johann Sebastian to become his successor as organist of the Marienkirche, requiring that Bach should marry his daughter first (she was a bit old and not so beautiful). The composer/organist had previously made a similar proposal to George Friedrich Händel. Like Händel, Bach politely refused but stayed in Lübeck for almost four months to study Buxtehude's music. It was a time extremely well spent and of considerable influence on Bach the composer. The four months stretched a holiday, that was only supposed to last four weeks, to such an extent that Bach almost lost his job in Arnstadt. Much of the music that Buxtehude wrote (including a lot of vocal church music) has been lost and it is partly thanks to the transcriptions that Bach made during his stay in Lübeck from Buxtehude's compositions that we now know how that music sounded. Nowadays Buxtehude is seen as someone who occupied a unique place in music history, as a composer who had a considerable influence on composers who would eventually surpass him in fame (Bach and Händel) and who was also a contemporary of Heinrich Schütz, the man who is seen as a founding father of lutheran baroque. A few cantatas by Schütz will be on the programme on Saturday morning, together with other God-praising works by Telemann and, of course, Bach. That's for Saturday, tonight BachFest will start, for me, with Johannes Passion, a performance were Bach's oratorio is staged with a ballet. A consortium of disciplines in which clerical music is paired with worldly dance. More to follow. - Wouter de Moor For BACH/BLOG see also:

After productions of Der Ring des Nibelungen and Tristan und Isolde, De Nederlandse Reisopera once again sails the stormy waters of the Wagner drama with Der Fliegende Holländer He would rather die ten times than sail the seas for one more day, but the curse that has struck him has condemned him to roam the earth forever. He has become discouraged, only the possible perishing of the world seems to offer him a solution. Every seven years he is allowed ashore to find a woman who can rid him of his curse. To find a woman who - by a vow of eternal fidelity - can give him the peace he so desperately seeks. In Amsterdam we didn't have to wait seven years for Der Fliegende Holländer to dock again. Last weekend it was exactly five years ago that the captain of the ghost ship gave its semi-concertante acte the presence in the Concertgebouw. Where the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, conducted by a conductor of Bayreuth-fame, Andris Nelsons, gave a rather cumbersome reading of Der Fliegende Holländer on that occassion, Benjamin Levy, in a production for De Nederlandse Reisopera, led the Noord Nederlands Orkest with relatively swift tempi and a swinging impetus through the turbulent waves of the opera that can be considered as the beginning of Wagner's mature oeuvre. Director Paul Carr uses the overture to introduce the audience to Senta's obsession before the libretto does. We see a woman in a wedding dress, her arms clinging to a book, in a certain state of frenzy. Longing for a man who is out of reach: like a teenage girl who dwells at the poster of a pop idol. Almost religiously inspired, Senta claims a leading role in the story that follows. In search of fulfilment, she will sacrifice her life so that the Dutchman can be freed from his curse. She will find her reward in a life after death with Der Holländer (a transfiguration in love ). We look at a projection of a big eye, as if Senta is taking us along in the story that unfolds, looking at it through her eyes. This production of Der Fliegende Holländer is, following their excellent Ring des Nibelungen and the mother of all Erlösungsbedurftige operas, Tristan und Isolde, the next triumph in the field of Wagner from De Nederlandse Reisopera. From the overture on (was a stormy sea ever more strikingly turned into music than Wagner does here?) dancers play an important role. In beautiful scenery, abstract enough to trigger the imagination and specific enough not to get lost in the story, dancers, singers, video projections and the clever use of stage sets makes that the turbulent sounds that come from the orchestra pit find in the things shown on stage a worthy partner. Motion is key, no Park & Bark (a stiff declamation of one's lines) but motion that comes with dynamic scenery sets that transform the stage in the ship of Daland, turn the entrance of the Dutchman into a memorable scene and, in a beautiful scenery change with open curtains, make the stage into the atelier where Senta, obsessed with the story of the Dutchman, becomes the target of mockery. Mockery of her fellow tailors in the atelier for wedding dresses who fight their own loneliness and uncertainty while waiting for the safe return of their husbands with singing and dancing. Sound and image do justice to the ferocity of the sea, which is both a décor of action and a reflection of the stormy inner lifes of the protagonists. Aile Asszonyi performs the role of Senta with passion and fury. With a voice in which, besides broad, romantic panoramas, a place is reserved for belcanto. Powerful, fragile and beautiful. There is, after all, no real drama without real beauty. Beauty that dies, at the moment when she puts the knife in her own belly, thus liberating the Dutchman and eventually, although that remains a matter of interpretation, also herself. As a sailor Senta's father Daland is a rough, naive man who, blinded by money, finds out too late which doom the Dutchman has in store for his daughter. In Yorck Felix Speer, no stranger to the Wagner repertoire, he has already played in Das Liebesverbot (sparsely staged, please see this reference as a plea for a new production of it), Daland finds a singer who shows, besides strength, a certain humorous quality. As is the case with his fellow members of the cast Speer's singing qualities are accompanied by a good stage performance and an enjoyable talent for acting. This production is a reminder of what the story of Der Fliegende Holländer actually is. A ghost story, in which the Dutchman and his crew were as gothic & undead as my 19th century horror loving heart could have wish for. Beautifully done and a reminder of Dracula, that most famous representative of the undead, whose novel was published exactly 120 + 1 year + 1 day ago (26 May 1897). With Der Fliegende Holländer Richard Wagner was still two operas removed from Das Rheingold, the first opera of Der Ring des Nibelungen, the opera cycle with which he would write music and theatre history, the tetralogy that would anticipate 20th century film music and a whole lot more. In Der Fliegende Holländer Wagner already plays with the idea of the leitmotif, those ´directional indicators of feelings´ with which he would string his Ring operas together. Although still a long way from the Gesamtkunstwerken that he had in mind, Wagner shows himself in Holländer already a true master in integrating music and theatre. A craftsman in building expectation and creating suspense. In this production of De Nederlandse Reisopera, Der Fliegende Holländer is a dynamic piece of music theatre that is above all an ode to Wagner the theatre man. It’s a production that makes you longing for more and nourishes the hope that the Reisopera will devote themselves to an opera of the sorcerer of Bayreuth again in the not too far away future. De Nederlandse Reisopera, Theater Carre, 27 May 2018 Conductor: Benjamin Levy Noord Nederlands Orkest Choir: Consensus Vocalis Regie: Paul Carr Choreography: Andreas Heise Decor- en costumes: Gary McCann Light: Alex Brok Daland: Yorck Felix Speer Senta: Aile Asszonyi Erik: Samuel Sakker Der Steuermann Dalands: Thorsten Büttner Mary: Ceri Williams Der Holländer: Darren Jeffery - Wouter de Moor Wagner & VampiresIn 1901, Der Fliegende Hollander was performed for the first time at Wagner's Festspielhaus in Bayreuth (the opera had premiered in Dresden in 1843). There was an Irish writer in the audience who had made a name for himself a few years earlier, in 1897, with a novel about a vampire. Of all the undead bloodsuckers that appeared in stories and poems in the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, Dracula is by far the most famous. A name that has become almost synonymous with vampire. When Bram Stoker died, on April 20, 1912, a short story was found in his legacy: Dracula's Guest. The story describes the journey of Jonathan Harker, not mentioned by name here, who wanders through Munich and attends on Walpurgis Night, prior to his trip to Transylvania, a performance of Wagner's Der Fliegende Holländer. Bram Stoker was not only a writer but also a man of the theatre. As a friend, admirer and manager of the famous English actor Henry Irving, he had made acquaintance with the Holländer-myth through Irvings' interpretation of Vanderdecken, a play about the Flying Dutchman. The fate of the Dutchman shows striking similarities with that of a vampire. Infamous for wandering the earth for eternity (with the idea of eternity as an unimaginable curse). Eternity that removes mankind from its humanity (we come across something likewise in Tannhäuser, when Tannhäuser wants to leave the godly world of the mountain of Venus). (A nice thing to mention in this short elaboration about the Wagner-Stoker connection is that Bram Stoker was friends with Bayreuther house conductor Hans Richter, discussed with Richter theatrical matters such as stage lighting, and that it was one Joseph Harker, a set designer from the environment of Irving, who designed the stage sets for productions of Lohengrin & Parsifal for Convent Garden in London.) While the most important vampire novel of all time was written with the wandering Dutchman in mind, Richard Wagner was aware of vampires when composing Der Fliegende Holländer. Whether or not he had read Polidori's The Vampyre (the most famous vampire novel in the mid-19th century) is not known, but he was certainly familiar with the opera that was based on that novel. In 1833, Wagner wrote additional music for a performance in Wurzburg of Heinrich Marschner's Der Vampyr. From a performance of Der Fliegende Holländer, we make a sidestep to Der Vampyr from Marschner in order to end up with Stoker’s Dracula for a short contemplation on Jonathan Harker. The man who, after his adventures in Transylvania, comes to the conclusion that his visit to Der Fliegende Holländer has anticipated his confrontation with Dracula in uncanny, multiple ways. Like in the story of Der Holländer, what used to be just a legend turns out to be hard, cold reality. And as in the story of Der Holländer it was a woman who sacrifices herself, in this case his fiancée Mina who gave herself to Dracula in order to free the world from a great evil. What made Harker of all of this? That legends are not just cultivated sublimations of human traits but have an eerie foot in reality? That the undead soul that roams the world was not just the product of a grim fantasy but in fact a human being of flesh and blood? It was a realization that could make a possible next visit to Der Holländer an uncomfortable and even undesirable one. Perhaps is was better to confine himself, for future entertainment, to operettas. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed