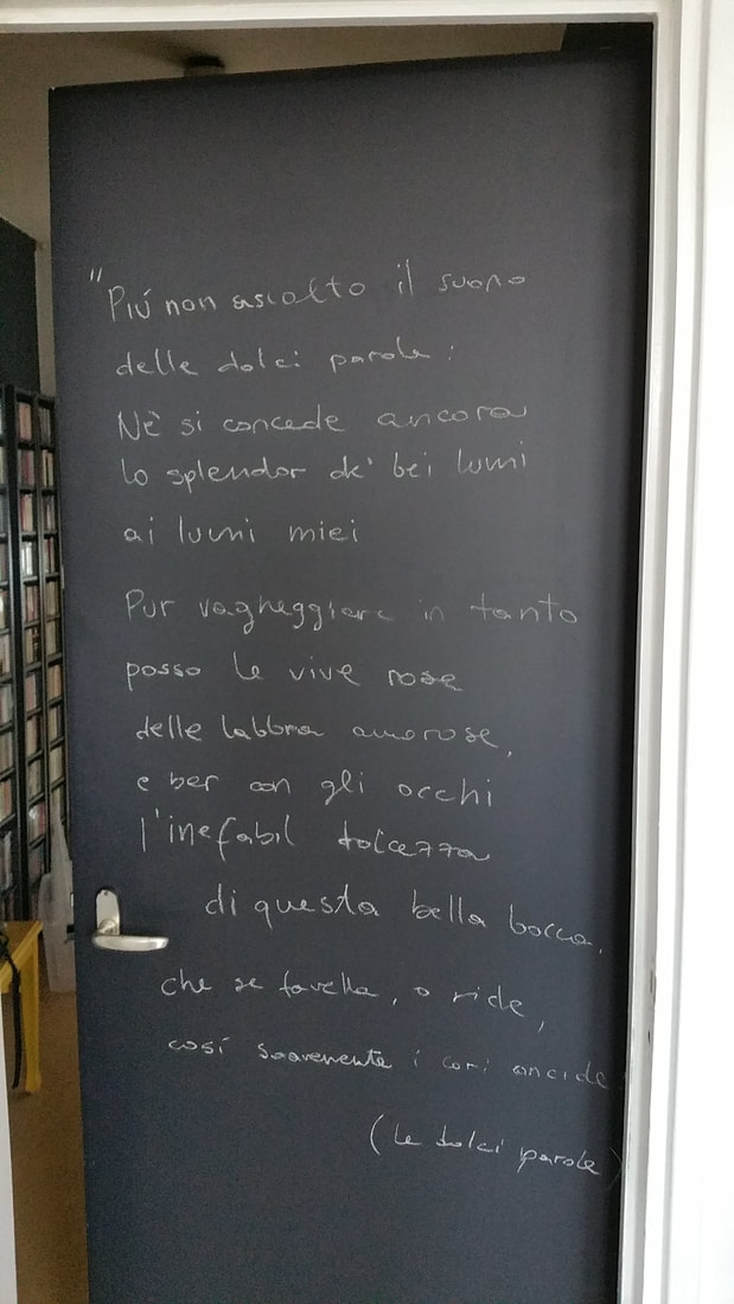

The Dutch-Swedish composer completes, with a world premiere, his cycle on the 17th-century Swedish queen Christina The Swedish queen Christina refused to marry, did not want to have children, could (as a direct consequence) not provide a successor to the throne and voluntarily abdicated and handed over the crown to her cousin. Her life, the subject of controversy and wild speculation (did she have a relationship with a woman?) has already been filmed - in 1933 with Greta Garbo in the lead role and her grave was - more than 300 years after her death - violated more than once (for further investigation - was she perhaps not secretly a hermaphrodite?) The Dutch-Swedish composer Klas Torstensson was no less fascinated by the life of the 17th-century queen from the land of his birth and dedicated a cycle to her, composed over a period of more than 10 years. At May 24th this cycle was completed with the world premiere of its last movement, L'autunno di Christine. A piece of music in which Christina, in the person of soprano Charlotte Riedijk, reports of her earthly passion and post-mortem rage. For the first part of the Christina cycle Torstensson draws from his own In Grosser Sehnsucht (a song cycle about remarkable and tragic women) and continues to build on the music we also know from his opera The Expedition. A musical landscape in which the contrasts between the composers who once served as an example to him, Varèse and Xenakis, and the Puccini-like lyricism with which he created a sensation in The Expedition, are explicitly searched for. Tonality as a building block, for love is not possible without it, but without sailing the seas of cheesiness. Besides melodies that please, Torstensson offers performers and listeners some challenges - challenges of a physical kind for the performers, because what is difficult to compose should not be too easy to play and therefore not too smooth for the listener to listen to. It's easy, and lovefully, to get lost in the musical panoramas that Torstensson carves out of aural basalt. In a live setting it is all the more striking that what is scarce, the accompaniment of Riedijk in the first movement by just the violin of Joseph Puglia, is no less in strength and eloquence than what is added to Christina's story at a later stage with a more extensive set of instruments. Even more than the percussion that abruptly ends the lyrical beginning of the third movement, it is the pregnant force of the continuation that attracts the listener and holds him in its grip. With descending tones we are entering Christina's rage over her desecration and the timpani-led bass theme - known from The Expedition - creates, in the tradition of the best film music, suspense and expectation. Torstensson may be drawing from musically complex patterns, his orchestration does not lose itself in mathematical detachment and remains, with a great feel for human proportions, focused on both head and heart. In changing combination with each other he uses different instrument groups to colour a variety of timbres. It are Nordic sounds that show a respect for nature, sounds that contain the elements that make his music sound organic. The inevitable references of a 21-century Mahler, Sibelius or Bruckner impose themselves. It is mightily beautiful. Even more than for orchestral power, Torstensson has an ear for the human voice, the soprano of his wife Charlotte Riedijk, whom he never - as if he loses the vulnerability of man in his struggle against the elements never out of sight - buries under the aural concrete on which he builds the house in which the misunderstood queen tells her story in three different languages. In Italian, Christina talks about the bittersweet sides of love, reports about the violation of her grave, and her anger about it, with the dimensions of the coffin proclaimed in Swedish as a funny intermezzo - thanks to the acting qualities of Riedijk. In French she looks back on her role as queen, after which in Italian she tells the story of her platonic love for Cardinal Azzolino. Encrypted words whose meaning is musically expressed by claves (wooden sticks specially made for the oocassion by Torstensson). The story of Queen Christina ends with her epitaph and the sound of a little bell that freezes time and echoes the hope that the queen, who did not let herself be dictated by laws, has finally found peace, free from grave offenders. Torstensson's Christina cycle was accompanied by psalms of Huygens and madrigals of Monteverdi and Gesualdo. The late madrigals of Gesualdo (of which we heard a selection from the sixth book) are musical confessions and cries of despair. The longing for inner peace and subsequent death wishes of a man who seeks absolution for the murders he committed on his adulterous wife and her lover. A hunger for salvation from earthly suffering with the idea of eternity as an unspeakable curse. The composer-murderer has this in common with the captain of that ghost ship who waits for me on Sunday when Wagner's Der Fliegende Holländer set sails to Amsterdam. But more about that later. Muziekgebouw aan 't IJ - 24 May 2018 Klas Torstensson Christina Cyclus Carlo Gesualdo Madrigali a cinque voci, Libro sesto: Claudio Monteverdi Confitebor terzo alle francese (Selva Morale e spirituale) Constantijn Huygens 5 Psalms for solo voice Performers: Sinfonietta Riga Normunds Šnē conductor Joseph Puglia violin Charlotte Riedijk soprano Consensus Vocalis Agnes van Laar soprano Chantal Nysingh mezzo soprano Franske van der Wiel alto Japser Dijkstra tenor Christiaan Peters bass Punto Bawono lute Klaas Stok conductor - Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

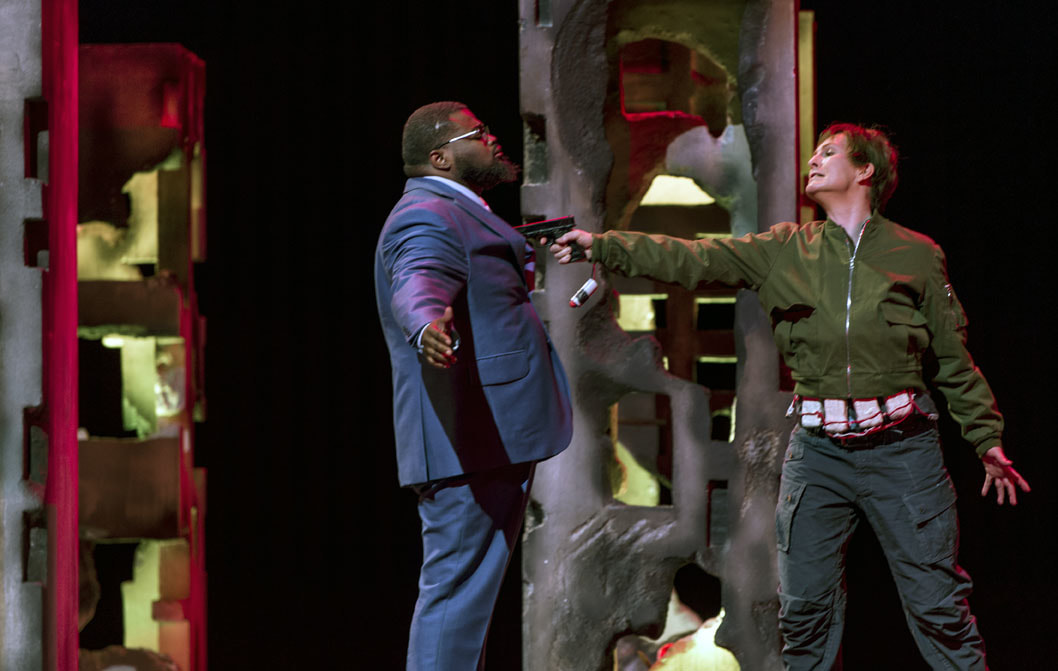

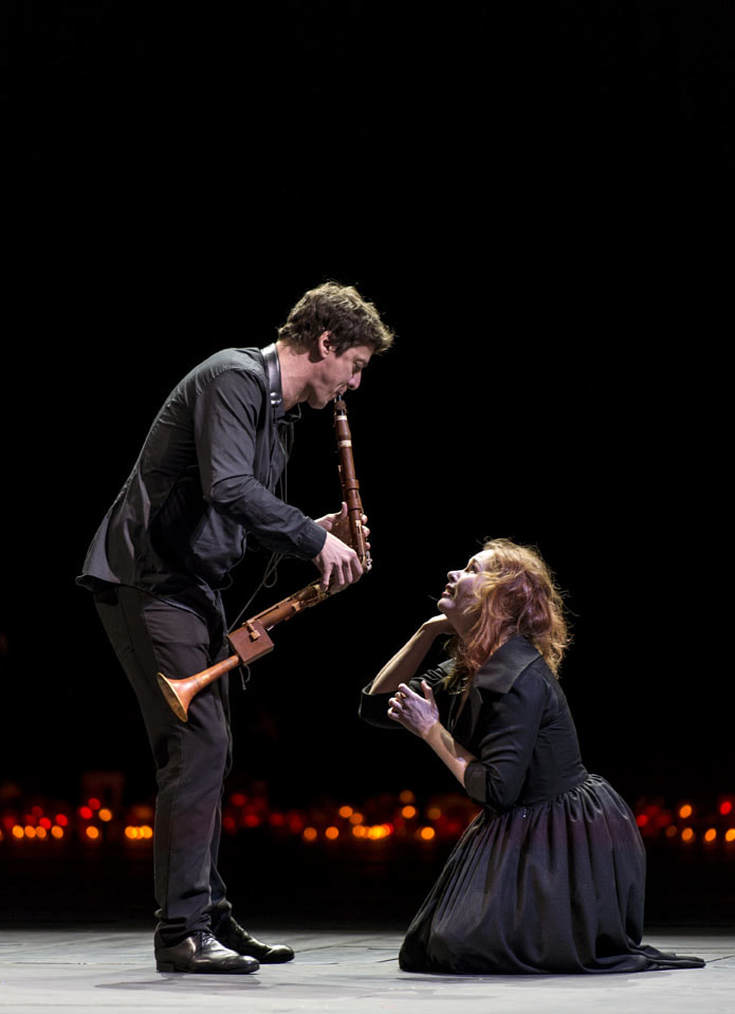

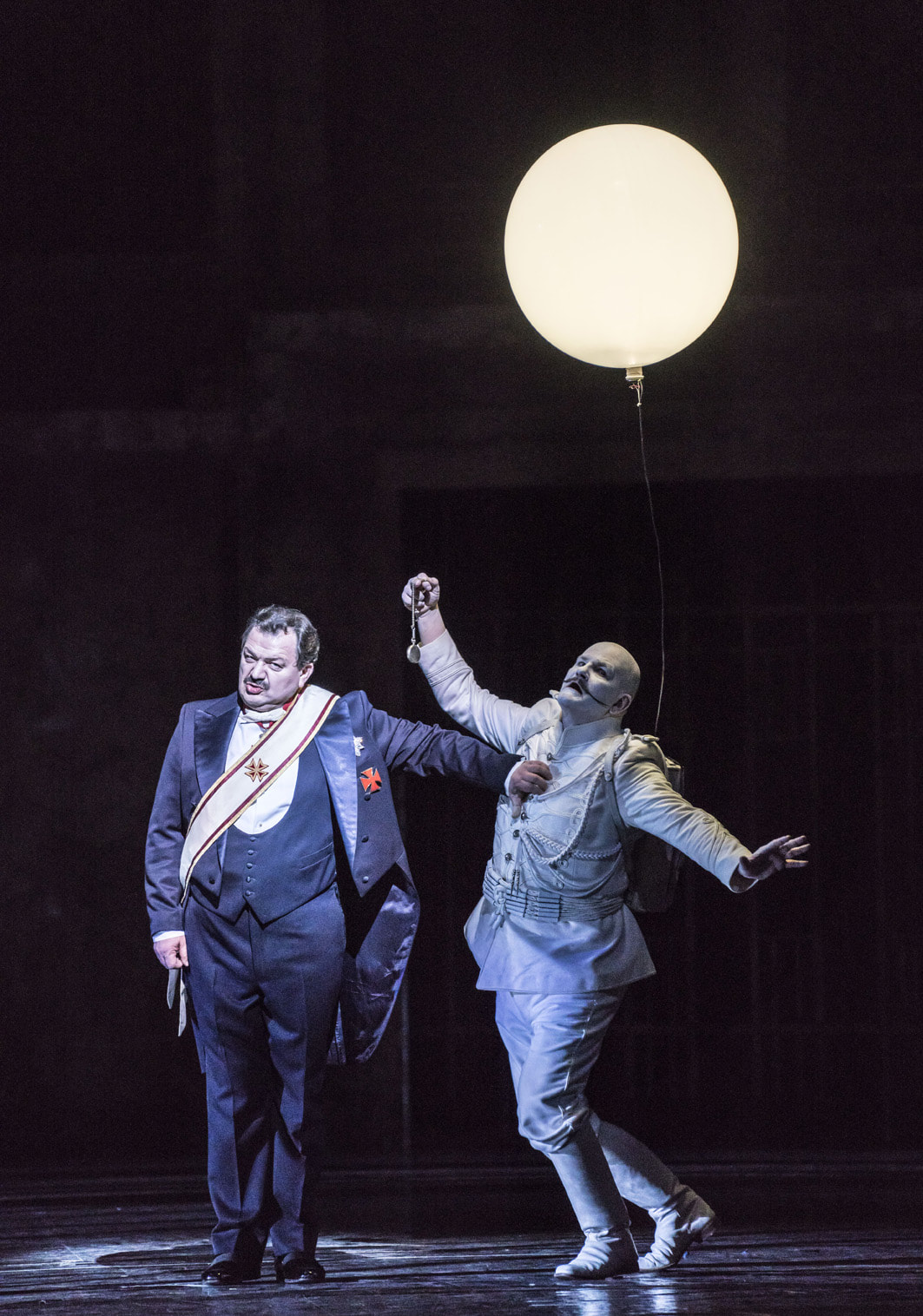

La Clemenza di Tito, a production by director Peter Sellars and conductor Teodor Currentzis that supplies Mozart's last opera with a topical outlook. After Salzburg and Berlin it visits Amsterdam. A wave of horror went through the Muziektheater. It had just been announced that Teodor Currentzis was ill and had to leave his duties as conductor for this afternoon's performance to his assistant Artem Abashev. Currentzis, the Greek-Russian boy wonder of classical music, has become an attraction on his own. A self-proclaimed saviour determined to give the genre that is, supposingly or not, on life support a much needed shot in the arm. (Here classical music meets heavy metal, if I had to believe the media the latter is in a state of deadlock for as long as I can read.) I was not able to judge whether it made a big difference or not - I did not see another performance to compare - but it can be assumed that this La Clemenza di Tito, a production which, after Salzburg and Berlin, is in its third series of performances, with an assistant-conductor who was closely involved in the rehearsals, was carried out entirely according to Currentzis's wishes. A HIP-style approach with swift tempi and contemplative slow-downs - executed with the energy that can be expected from an orchestra of which the majority of its musicians play their parts while standing on their feet. Besides the orchestra and its enigmatic conductor there was Peter Sellars who gave the opera a contemporary look and there was, of course, Mozart. Above anything else, there was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Because, as is often the case with opera productions in which directors expressly seek their own added value in centuries-old repertoire, it became (also here) vividly clear that it is ultimately the music that remains. La Clemenza di Tito is an opera, a rush job, written by a man, Salzburg's most famous son, who at the time of accepting the assigment only had six months to live. It is an opera (as demonstrated by the semi-concertant performance with which the Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century toured Holland last year) that can stand on its own feet. Whether this Sellars/Currentzis production is a valuable addition to the catalogue of Mozart-operas, and that of La Clemenza di Tito in particular, others may decide, certain is that Sellars (who has passed 60) lives up to his reputation of enfant terrible for those who are attached too strong to tradition. In this production Sellars does what he does more often, making connections between past and present, explicitly seeking the involvement of topical subjects. Things that should otherwise not matter (the colour of the cast) receive their place in the narrative while things that are drawn to current events (e.g Sesto becoming a terrorist) inadvertently emphasize that it is not Mozart's opera that needs saving from oblivion but Sellars', undoubtedly, good intentions. Sellars adapts Tito's story and together with Currentzis he brings other pieces of Mozart's oeuvre to the show. The addition of extra music in a for this occasion adapted storyline works wonderfully well in the first act. The Adagio & Fugue gives, for instance, an extra depth to Sesto's reflections on his role in the rebellion against Tito and the two pieces from Missa KV 427 (Benedictus & Hossanna and Laudamus te), brought in to honour Tito, grow into an excellent showcase for the choir of musicAeterna - it is pure gold that sounds here. But what works well before the break decends into emo-kitsch in the second half. In the second act, we make a jump to the recent past: the attacks, and their aftermath, in Paris, Brussels, Nice and Manchester. We see a wake with flowers and candles in commemoration of the victims, in which the Kyrie from the aforementioned Missa serves as a kind of John Lennon's Imagine on piano. It are images that are still too fresh to make an impression in the theatre. Where the adjustments of Sellars before the break feel natural, they loose their credibility in the second part. Tito turns into a soap that unintentionally reveals that the original libretto was not so bad to begin with. In the original libretto Tito is supposed to be dead after Sesto attacks him, he seems to be alive after all when it turns out that another man was stabbed by Sesto in Tito's place. Sellars thinks of this as weak dramaturgy (indeed) so he lets Sesto attack (and wound) Tito, visibly for the audience, after which Sesto, after having been imprisoned and handcuffed, is happily left alone with Tito on his deathbed (the perhaps not so strong original dramaturgy is replaced here by something as equally, if not more, far-fetched). Tito, initially determined to punish his good friend's betrayal with death, grants Sesto mercy. On the Mauerian Trauermusik, in the face of a grieving crowd, the generous king, as a major departure from the original plot, eventually dies of his wounds. From the aforementioned production of the Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century, we again encounter the Irish mezzo-soprano Paula Murrihy in the role of Sesto. As a mezzo-soprano in a male role (it regularly occurs in Mozart) she/he is a white traitor of a black king. Tito, fiercely sung by Russell Thomas, and his courtiers are all black, with Annio, a beautiful role of Jeanine De Bique (another mezzo-soprano in a male role) as his confidant. In the Vitellia of Ekaterina Scherbachenko, anger and despair are fighting a vicious fight with each other. A inner struggle that is made explicit in the scene - I found it one of this staging's stronger ideas - in which she is joined on stage by Florian Schüle, whose basset horn sounds like her inner voice. Janai Brugger is a sensitive Servillia and the cast, where it comes to the most important roles, is completed by the warm bass of Dutch National Opera-veteran Sir Willard White. In this production, La Clemenza di Tito is a piece of music theatre that makes its case not so much for Tito-the-opera as for the Mozart-the-composer. The overly adapted storyline, the eagerness to make an emotional impact and the frantic attempt to stay on top of the news in an opera production, triggers an, all too strong, attention-shift from staging to music. For all what goes wrong (mainly in the second part) we get back a beautiful final chorus, excellent, but the music becomes, by that time, more a soundtrack to invented scenery than part of a coherent whole. It is therefore, with the music of the divine Mozart still ringing in my ears, that for a future return to this production an audio-only document will most likely suffice. The Dutch National Opera 13 May 2018 Dates 7 May until 24 May 2018 Musical director: Teodor Currentzis (Artem Abashev conducted on 13 May) Orchestra: MusicAeterna Chorus: MusicAeterna Stage director: Peter Sellars Tito Vespasiano: Russell Thomas Vitellia: Ekaterina Scherbachenko Servilia: Janai Brugger Sesto: Paula Murrihy Annio: Jeanine De Bique Publio: Sir Willard White - Wouter de Moor

Time for an organ, a world premiere (Memories III by Jan Welmers) and Bruckner's mighty Eighth (by the Nederlands Radio Filharmonic Orchestra conducted by David Zinman). It was, if I am not mistaken, Pierre Boulez who once expressed his frustration about the fact that performance practice did not keep up with composers practice. That music developments were delayed because it took too long for new music to become accepted. It was a disappointment, probably announced because concert programmes would not provide enough room for new music. An aversion to venues that would hold on too much, whether or not under pressure from public and sponsors, to repertoire that could be regarded as accessible and had already proved itself. Much of what is now repertoire of stainless steel was once considered unplayable (with the Ninth of Beethoven as a famous/notorious example). With the obviousness with which much of that previously misunderstood material now finds its way to the concert hall, it is sometimes difficult to imagine the incomprehension that composers met when a new composition was considered too complicated. Anton Bruckner, for example, has had his share of aversion shown to his work. Not only by renowned Romantic-haters like Eduard Hanslick but also by musicians who were generally well acquainted with his music. For his 8th symphony the teacher's son from Ansfelden had to deal with criticism, coming out an unexpected corner. Hermann Levi, a collaborator for a long time, the conductor of a very successful performance of Bruckner's Seventh, worked his way up to the score of the Eighth and advised the composer to work on it a bit more. Those words didn’t fall in deaf man ears, it brought the ever doubting Austrian to many revisions (which were, during and after his lifetime, continued by others, amongst them Haas and Nowak). In 1892, four years before Bruckner's death, it finally came to the premiere of the Eighth. The symphony was to be performed only twice during Bruckner's lifetime after that. Last week, it was performed two times in the Concertgebouw. Once by the Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Jaap van Zweden (I missed that one) and once by the orchestra with which Van Zweden recently recorded a complete Bruckner cycle: the Nederlands Radio Filharmonic Orchestra. That orchestra, which has just announced that Karina Canellakis will be the new chief conductor as of 2019, the successor to Markus Stenz, was led for this occasion by David Zinman. Zinman is a man who likes to keep a sober, earthly perspective. That was anyway the conclusion I drew from his reading of Bruckner's 8th symphony. He distances himself from religious panoramas and shows little interest in the nickname of this symphony: the "Apocalyptic". In relatively swift tempi and with an exceptional sense of proportion, the American conductor worked his way through the Eighth. In a reading in which, and this is very much a recommedation, the first two movements were an equal partner of the magnificent third one: the Adagio. The Adagio, in which Bruckner takes a dip in the sound world of Robert Schumann's second symphony, was here not so much an ascent into the thin air of higher spheres as well a trip through Teutonic Lowland. A landscape where flowers grew out of the sound of a harp and the sultry air, on a beautiful spring afternoon in May, breathed comfort and redemption. At his worst, a Bruckner symphony is a story in which the narrator fails to make his point (the 4th and 5th symphony can be problematic for me in that regard). But also performances of the Seventh and Eighth in which repetitions can take on a compulsive character, can be hard a hard pill to swallow. At the beginning of the 8th symphony, the sound of a flute suggests the awakening of the world. An awakening, an announcement, with which a symphony begins that bears in it the character of a salutation - as if a message is repeatedly proclaimed. For Zinman, this repetitions always retained a fresh character; it gave the music a forward moving power without falling into the trap of a mechanical repetition of moves. With the awakening of the symphony, nature emerges and even more than a cathedral of sound - a reference that surfaces rather often when it comes to Bruckner's music - it is nature that finds in this performance an almost perfect depiction. Here the notes of Anton Bruckner, once exposed to gravity and time, are made into a conjuction of organic impressions that emphatically sailed through Mahlerian waters. It was halfway the final movement (about fifteen minutes from the end) that the violins let go of the decisiveness with which they have worked themselves through the symphony up to that point - as if they were overcharged by the demands that Bruckner maked on bow and fingering. Those vicious string arpeggios, that enable the majestic theme, played by the brass, to rise - it's the perfect soundtrack for a SF and/or superhero movie - stumbled. Very briefly, because this performance, which seamlessly kept its attention span from beginning to end, was one of exceptional quality. Time will tell if Jan Welmers' new composition (Memories III) will become a repertoire piece. This piece for organ was played by Concertgebouw organist Leo van Doeselaar. A world premiere on an instrument that referred to Bruckner the organist, with musical means that referred to Bruckner the composer. It was a piece of music in which you could not only hear the notes but also feel them. It proved to be a perfect prelude to a sensuous ride through the world of Brucker's mighty Eighth. Concertgebouw 12 May 2018 Jan Welmers – Memories III (world premiere) Organ: Leo van Doeselaar Bruckner – Eight Symphony in c Conductor: David Zinman Nederlands Radio Filharmonic Orchestra - Wouter de Moor

In 2014, the Dutch National Opera was the first to present a fully-staged version of Arnold Schönberg's mega-cantata. This season, that production returns. As early as 1927, serious thought was given to a fully-staged production of Arnold Schönberg's Gurre-lieder, but it was not until 2014, at express wishes of conductor Marc Albrecht and under the direction of Pierre Audi, that this idea really materialized. Once started as a song cycle for soprano, tenor and piano (an entry for a competition of the Vienna Tonkünstler-Vereins), the composition would burst out of every conceivable musical joint by the time it was completed in 1911. At the premiere in 1913, under the baton of Franz Schreker, 757 musicians took part (thereby almost reducing Gustav Mahler's 8th symphony - in which more than 400 musicians took part at its premiere in 1910 - to a piece of chamber music). That enormous number of the first performance is not reached in this production of The Dutch National Opera, only 235 musicians populate the stage and orchestral pit, but the use of musical means is still far above average when compared to other pieces in the Late-Romantic repertoire. In the story of Gurre-Lieder - based on a poem by Danish writer Jens Peter Jacobsen (1847-1885), who in turn drew inspiration from the story of King Waldemar Atterdag (1320-1375) - Waldemar is having a love affair with Tove. An affair to which Waldemar's wife Helvig do not react too subtly: she gets Tove killed, after which Waldemar fell into insanity. Schönberg captures all of this in opulent music in which he deliberately pushes more than a few boundaries. Gurre-Lieder was a point of arrival for Schönberg, the conclusion of an era, not only for himself but also for the history of music up to that point. From now on everything had to change. When the orchestration of Gurre-Lieder was completed in 1911, he had already gone on the atonal path with Erwartung in 1909, and after Gurre-Lieder, the man who wanted to emancipate the dissonant no longer wished to look back. (That his music after that was considered merely atonal Schönberg contested. His music might have come about according to other musical principles, but it still contained tones. According to him, the fact that the dissonants were experienced as ugly was mostly a matter of conditioning - by upgrading the dissonance to something with which beauty could be expressed in addition to ugliness and conflict, the musical vocabulary could be considerably expanded.) Gurre-Lieder does not suffer too much from dissonants. Their presence is amply counterbalanced by pleasant, at times coquettish, harmonies. Music in which Waldemar and Tove share their ecstasy and their fear of loss. As it befits a good Late-Romantic work, in Gurre-Lieder we also find a pre-occupation with death. The fear of the end, before the end is even there. Finiteness that can only be overcome with love. The end comes, for Tove and also for Waldemar, who after the message of the Waldtaube about Tove's death, must be considered lost for this world. They find each other again, the king and his beloved, in nature, transfigured in love, transcending death. A gathering that we find, more than on stage and in the sounds that rise from the orchestra pit, back in the score, because in Gurre-Lieder the music is quite dense. Pleasant, sensual tones together with musical saccharides are transformed into a tapestry of sound in which many who are enchanted by it still regret that the composer, Schönberg, would devote himself after the completion of this super oratorio mainly to atonal music. Not by me because Gurre-Lieder is at its most interesting in the moments when Schönberg grants the listener a glimpse into the future. When he, rather than dwelling in Romantic loftiness, looks forward to the music that will come after Gurre-Lieder, the dodecaphony, and refers to cabaret. The Sprechgesang van Der Sprecher and the cabaratesque character of Klaus Narr are both highlight and delight. Here Schönberg explicitly seeks the contrast with the (all too) Romantic density of the piece – it lets the audience some air and gives Gurre-Lieder more texture. The massive orchestration (I will think of it the next time I see someone questioning the orchestration of the symphonies of Robert Schumann for being too dense) gave the impression that what works, for example, well in Tristan und Isolde, an approach that emphasizes the passion that speaks from the score, has the opposite effect in the case of Gurre-Lieder. The idea surfaced (and never left) that Marc Albrecht could have suffice with a lighter and more transparent approach - whether or not accompanied by a further reduction of the orchestra - because the singers were hardly able to cope with the sonic violence to which they were subjected by orchestra and conductor. For this production of Gurre-Lieder, the piece has been adapted on a few points. The play begins with a poem by Jacobsen, recited by the Sprecher, who normally appears only in the third part, while Klaus Narr, who normally also only appears in the third part, shows up next to Waldemar right from the start. It are interventions that glue together on stage what has been cut by the different songs and orchestral interludes. It inadvertently sheds light on the lack of a strong narrative and makes clear what Gurre-Lieder is not: an opera or a music drama. Even in this production, in which designer Christof Hetzer depicts decay in a beautiful and atmospheric way - in an environment where you can imagine Götterdämmerung or Elektra - the operatesque Gurre-Lieder remain a mega-cantata with beautiful pictures. Rather a piece with compelling moments than a compelling piece. It wasn’t meant to be, also after a second visit. The hope that Schönberg's Late Romantic super cantata would grab me turned out to be largely in vain. Again, the piece did not seem to me the opera that Marc Albrecht and Pierre Audi apparently see in it. The coin, when it comes to Schönberg's Late-Romantic compositions (with the inevitable Verklärte Nacht as its most famous example), has not yet dropped. This is, in Gurre-Lieder's case, partly due to the sumptuous orchestration in which Schönberg refers to Wagner and Richard Strauss but remains miles away from them in terms of expressiveness. I could appreciate it better now than four years ago when Gurre-Lieder didn't speak to me at all. Then the supposingly next-step-after-Wagner turned out to be a seven mile step backwards - both musically and dramatically. But I had a better time this time, I managed to cope better with what is clearly an important piece in the musical canon. It was not the composers Schönberg himself refered to but the composers who were (partly) inspired by his Late-Romantic compositions (Korngold, Schreker) who made Gurre-Lieder's music more comprehensible for me. A declaration of love, however, will have to wait. The Lied der Waldtaube is insanely beautiful (for the version of Jard van Nes with the Schönberg Ensemble you can wake me up at night), but the choral singing keeps puzzling, or better baffling, me – here Schönberg doesn't exactly present himself as the prodigal son of Georg Friedrich Händel to put it mildly. Waldemar Attevar was the historical character that formed the basis of the Waldemar of Gurre-Lieder. Attevar is Danish for "another day" and with the beginning of a new day Gurre-Lieder closes. A choir sings about the rise of the sun (Seht die Sonne) and it becomes clear how fed up Schönberg must have been with tonality. He must have meant this closing as a cynical joke. More than the (obvious) musical references of Gustav Mahler (Auferstehung) and Richard Strauss (who shows us with the intro of Also Sprach Zarathustra the true grandeur of a C major chord) I have to think of a Dutch stand-up comedian: Hans Teeuwen. He once concluded one of his shows with an epic poem that turned out to be a big joke - it was just a mash-up of clichés. He resolutely expelled the audience that had rewarded him with an ovation - refusing to receive their final applause. I couldn’t help thinking of Schönberg's refusal to receive the applause after Gurre-Lieder's successful premiere where he firmly kept his back turned to the audience. A few years earlier ( in 1908) the public at large had rejected the fresh air from other planets from his second string quartet ('Ich fühle luft von anderem planeten'), now they rewarded the stench of the overblown power chords with which he had set a closing bar behind music history with a standing ovation. He didn't want and couldn't hide his chagrin about that. By times, Gurre-Lieder took my breath away – be it not always for recommended reasons. Once home, the breath of fresh air, coming from the second string quartet, was more than welcome. The Dutch National Opera Dates 18 April - 5 May 2018 Conductor: Marc Albrecht Nederlands Philharmonisch Orkest Koor van De Nationale Opera Kammerchor des ChorForum Essen Director: Pierre Audi Stage and costumes: Christof Hetzer Waldemar: Burkhard Fritz Tove: Catherine Naglestad Waldtaube: Anna Larsson Bauer: Markus Marquardt Klaus Narr: Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke Sprecher: Sunnyi Melles - Wouter de Moor

|

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed