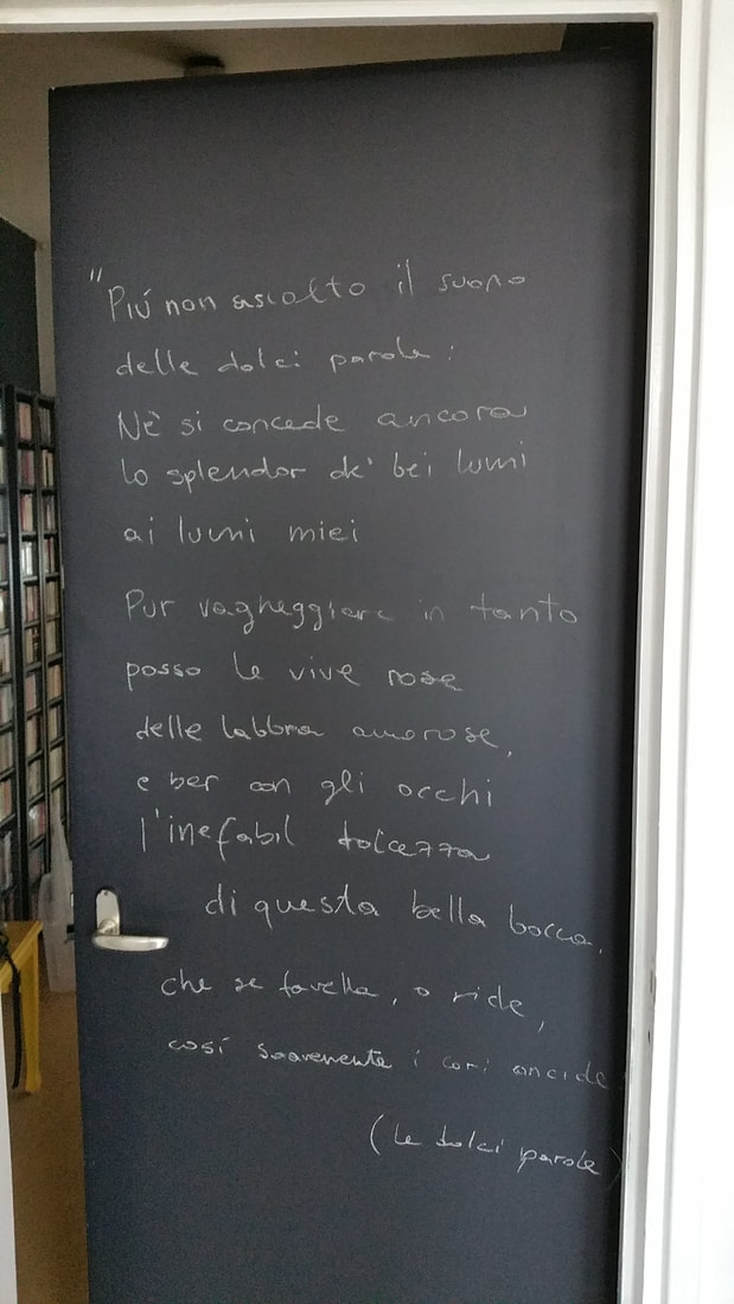

The Dutch-Swedish composer completes, with a world premiere, his cycle on the 17th-century Swedish queen Christina The Swedish queen Christina refused to marry, did not want to have children, could (as a direct consequence) not provide a successor to the throne and voluntarily abdicated and handed over the crown to her cousin. Her life, the subject of controversy and wild speculation (did she have a relationship with a woman?) has already been filmed - in 1933 with Greta Garbo in the lead role and her grave was - more than 300 years after her death - violated more than once (for further investigation - was she perhaps not secretly a hermaphrodite?) The Dutch-Swedish composer Klas Torstensson was no less fascinated by the life of the 17th-century queen from the land of his birth and dedicated a cycle to her, composed over a period of more than 10 years. At May 24th this cycle was completed with the world premiere of its last movement, L'autunno di Christine. A piece of music in which Christina, in the person of soprano Charlotte Riedijk, reports of her earthly passion and post-mortem rage. For the first part of the Christina cycle Torstensson draws from his own In Grosser Sehnsucht (a song cycle about remarkable and tragic women) and continues to build on the music we also know from his opera The Expedition. A musical landscape in which the contrasts between the composers who once served as an example to him, Varèse and Xenakis, and the Puccini-like lyricism with which he created a sensation in The Expedition, are explicitly searched for. Tonality as a building block, for love is not possible without it, but without sailing the seas of cheesiness. Besides melodies that please, Torstensson offers performers and listeners some challenges - challenges of a physical kind for the performers, because what is difficult to compose should not be too easy to play and therefore not too smooth for the listener to listen to. It's easy, and lovefully, to get lost in the musical panoramas that Torstensson carves out of aural basalt. In a live setting it is all the more striking that what is scarce, the accompaniment of Riedijk in the first movement by just the violin of Joseph Puglia, is no less in strength and eloquence than what is added to Christina's story at a later stage with a more extensive set of instruments. Even more than the percussion that abruptly ends the lyrical beginning of the third movement, it is the pregnant force of the continuation that attracts the listener and holds him in its grip. With descending tones we are entering Christina's rage over her desecration and the timpani-led bass theme - known from The Expedition - creates, in the tradition of the best film music, suspense and expectation. Torstensson may be drawing from musically complex patterns, his orchestration does not lose itself in mathematical detachment and remains, with a great feel for human proportions, focused on both head and heart. In changing combination with each other he uses different instrument groups to colour a variety of timbres. It are Nordic sounds that show a respect for nature, sounds that contain the elements that make his music sound organic. The inevitable references of a 21-century Mahler, Sibelius or Bruckner impose themselves. It is mightily beautiful. Even more than for orchestral power, Torstensson has an ear for the human voice, the soprano of his wife Charlotte Riedijk, whom he never - as if he loses the vulnerability of man in his struggle against the elements never out of sight - buries under the aural concrete on which he builds the house in which the misunderstood queen tells her story in three different languages. In Italian, Christina talks about the bittersweet sides of love, reports about the violation of her grave, and her anger about it, with the dimensions of the coffin proclaimed in Swedish as a funny intermezzo - thanks to the acting qualities of Riedijk. In French she looks back on her role as queen, after which in Italian she tells the story of her platonic love for Cardinal Azzolino. Encrypted words whose meaning is musically expressed by claves (wooden sticks specially made for the oocassion by Torstensson). The story of Queen Christina ends with her epitaph and the sound of a little bell that freezes time and echoes the hope that the queen, who did not let herself be dictated by laws, has finally found peace, free from grave offenders. Torstensson's Christina cycle was accompanied by psalms of Huygens and madrigals of Monteverdi and Gesualdo. The late madrigals of Gesualdo (of which we heard a selection from the sixth book) are musical confessions and cries of despair. The longing for inner peace and subsequent death wishes of a man who seeks absolution for the murders he committed on his adulterous wife and her lover. A hunger for salvation from earthly suffering with the idea of eternity as an unspeakable curse. The composer-murderer has this in common with the captain of that ghost ship who waits for me on Sunday when Wagner's Der Fliegende Holländer set sails to Amsterdam. But more about that later. Muziekgebouw aan 't IJ - 24 May 2018 Klas Torstensson Christina Cyclus Carlo Gesualdo Madrigali a cinque voci, Libro sesto: Claudio Monteverdi Confitebor terzo alle francese (Selva Morale e spirituale) Constantijn Huygens 5 Psalms for solo voice Performers: Sinfonietta Riga Normunds Šnē conductor Joseph Puglia violin Charlotte Riedijk soprano Consensus Vocalis Agnes van Laar soprano Chantal Nysingh mezzo soprano Franske van der Wiel alto Japser Dijkstra tenor Christiaan Peters bass Punto Bawono lute Klaas Stok conductor - Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed