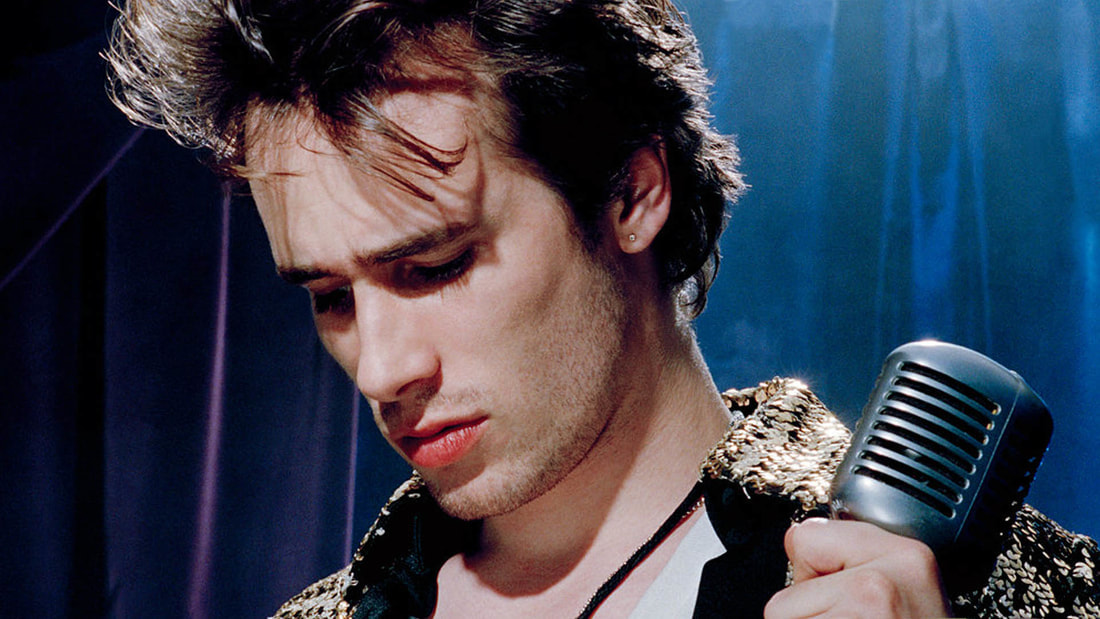

Pierre Audi's production of Tristan und Isolde is out of this world. How do you stage an opera that lacks action and fysical activity? How do you imagine an opera in which the music, much more the characters who inhabit that opera, tells the actual story? How do you keep the act on stage exciting when the real story takes place in the inner world of the main characters, when the core of the piece revolves around things that actually cannot be shown? After the kick-off in Paris and the next stop in Rome, Pierre Audi's production of Tristan und Isolde comes home in Amsterdam. On 18 January it had its Dutch premiere. Just like in his staging of the Ring des Nibelungen (a production that got me fascinated, by times obsessed, with the music of Richard Wagner), Pierre Audi chooses (with designer Christof Hetzer) to provide Tristan und Isolde with a stage on which the imagination of the drama is almost entirely left to Wagner's music. For instance, the audience does not have to know the exact meaning of the whale skeleton in the second act to understand the staging. The staging contains no key to a further understanding or deeper insight of the opera (one can consider this a shortcoming or a virtue, I liked it). When the opera starts, a black square hangs over the stage. During the overture large panels are ridden on the stage. "Why don't they keep the prelude free from stagenoise?" were my first thoughts but soon those panels, reminiscent of parts of a shipyard, turned out to be the setting of a scene that depicts what preceded the opera. It shows Tristan who, severely injured after his battle with Morold, goes to Isolde to be healed. (It are Isolde's words that reveal that he does this under the pseudonym 'Tantris' - we cannot completely suppress a smile because of so much supposed boldness.) When she looks Tristan in the eyes - and only then recognizes him (the pseudonym worked pretty well anyway) - she doesn't have the heart to kill him. As in more of his operas, Wagner chooses in Tristan und Isolde to start the story (by analogy with ancient Greek drama) just before the final climax - when most of the story (and the bulk of the action) has already been taken place. That story comes to us during the opera through retrospection. In this way Wagner is able to zoom in on what his main characters are really going through. The real story of Tristan und Isolde takes place in the heart and minds of the protagonists, their inner world. Here Tristan, Isolde, Brangäne, King Marke and Kurwenal walk around in an almost symphonic world that could be interpreted as Schopenhauer's world of the Will: the primeval forces that drive the world and everything in it. By the time Wagner started composing his Tristan, he was completely captivated by Schopenhauer. Schopenhauer who, in short, stated that we and everything we observe are only expressions (phenomenal manifestations) of the all-determining Will. The Will, the noumenal world, which lies beyond sensory perception, is a place where only music is able to provide us with a possible impression of it. It is the only place, outside the known world, where Tristan and Isolde really can be together. Following this premise Wagner made Tristan und Isolde the opera in which he abandones the idea of equating text with music. He turns this music drama into a world in which the music, the only thing that can lead us to the noumenal world, is predominant. This music draws itself along infinite melodic lines that represent a fierce desire of which the ultimate musical (and dramatic) solution comes with a B major chord, played by the orchestra at the very end of Isolde's "Mild und Leise" (by Franz Liszt coined, by means of his piano transcription, with the title "Liebestod"). Against this background (I take advantage of the possibility to interpret the stage scenery in a broad way) you might think of the big black square on stage as an artist's impression of this noumenal world. A black hole that conceals and suggests a space that is unattainable for observation. The world of Tristan is the world of a man who becomes aware of the things he has missed in life. He is no longer granted salvation by ignorance. The energy and lust he experiences is the result of being together with a woman who appears to be his soul mate. By that encounter with Isolde, the undefined aspects of his inner life that he has always carried with him are outlined. It is an encounter that contains a promise for the future, both hopeful and false, and reminds him of a time he will never be able to return to. Tristan and Isolde condemn each other to a life in which they cannot live with or without each other. This world, in which there is no salvation, Erlösing, in which the passionate desire of the love couple to fuse together turns out to be impossible, can only be escaped by a transfiguration in love, by death. With the musical depiction of turmoil that a human being, once he is in it, can't imagine will ever go away, Tristan is the opera that brought back the music that was closest to my heart 20 years ago. But more about that later. Before I stick an epilogue to this review that wanders to regions outside the world of opera (and classical music) this production and its stellar line-up deserves all attention. The American Stephen Gould is probably the best Tristan around at the moment. His experienced and purified Tristan (he has sung the role almost 70 times now) is joined by Ricard Merbeth, who, despite being relatively new to the role, made a convincing Isolde. (Merbeth was, incidentally, timid in comparison with the mighty Tristan of Gould, but she showed no signs of vocal limitations when she had to deliver on big moments - the high C in the second act was solid, no need for Elizabeth Schwarzkopf there). Merbeth's acting qualities were undisputed and together with Gould she delivered a couple of beautiful scenes (the love duet in the second act was most impressive). With Gunther Groissböck as König Marke, this production has a luxurious cast. At the end of 2016 Groissböck sang the role of Gurnemanz in Parsifal for DNO (also directed by Pierre Audi), a role he will be singing in Bayreuth over the next two years. In that theatre, where you are as close as you can get to Wagner, he will sing Wotan in a new Ring production for five consecutive years from 2020 on. For his role as Marke a firm "Hail to the King!" was entirely in place. As Marke he can hardly accept Tristan's betrayal, he initially refuses to believe it. Apparently it hurts him that his most loyal vassal apparently has been disloyal to him and he seems to blame Melot, the messenger of that betrayal, even more than Tristan himself. In König Marke of Günther Groissböck, the anger about that betrayal fights against the grief of the loss of a friend. Together with his impressive stage presence - there is a constant element of menace in his performance - Groissböck's warm and radiant bass-baritone makes Marke a person of conflicting character. He makes Marke the kind of person who can make a stay in the Wagner theatre such a rich experience. An experience in which it is as if you look into a mirror and see the human condition reflected in all its facets. BAYREUTH & HEAVY METAL This Tristan was a bit of a Bayreuther Festspiele reunion. Next to Stephen Gould, who sang the title role in Katharina Wagner's production of Tristan und Isolde, were Günther Groissböck (König Marke) and Iain Paterson (Kurwenal) who played in Das Rheingold last summer. Paterson ("I hear a lot of heavy metal and rock in Wagner, it's music with balls." Check) played Wotan and Groissböck (no stranger to Metallica, Slayer and Sepultura. Check. Rammstein is still open to debate) gave Fasolt an impressive impersonation in which he, by stumbling, gave new ideas to director Frank Castorf to spice up the staging. Chasing Freia, Groissböck (Fasolt) slid across the wetted stage floor (the daughters of the Rhine had kept themselves busy with splashing in the pool) and fell, head first, on top of his face. His first thought "I hope my teeth are still there" was quickly followed by a second one "Frank [Castorf] is going to ask me if I can do this again". That was exactly what happened. "Günther, Machen Sie das"! In Bayreuth, Groissböck also sang the role of Veit Pogner in Barry Kosky's new production of Die Meistersinger. If the first act was a warming-up, and the second act's love duet the first real highlight, then the third act was an all-embracing fever dream from which no waking up was possible. The third act has one of the most delightful contradictions in the world of opera. While he is deadly wounded, Tristan pulls out an impressive swan song. It is here that Stephen Gould - who by then faces an orchestra that has gained full momentum under the passionate baton of Marc Albrecht - lifts his performance from 'very good' to 'outstanding'. When Tristan dies and the light goes out behind the stage Isolde prepares for her final aria. It's time for everyone to die. This Jonestown solution - König Marke's words "Tot denn alles! Alles tot!" taking literally - is a conclusion similar to his Parsifal in which Pierre Audi also let everyone die. As if the corpse that lies on stage in the third act had made it clear all along: those who come to this place are doing so to die. Dutch National Opera 18 January 2018 (premiere): Dates 22 January until 14 February Conductor: Marc Albrecht Netherlands Philharmonisch Orchestra Stage direction: Pierre Audi Sets and customs: Christof Hetzer Tristan: Stephen Gould Isolde: Ricarda Merbeth Brangäne: Michelle Breedt König Marke : Günther Groissböck Kurwenal: Iain Paterson Melot: Andrew Rees EPILOGUEThe special thing about Wagner is that he keeps succeeding in stirring up feelings and emotions whilst making his music increasingly complex. Wagner uses advanced musical means to seek (and make connection) with the most elemently human feelings. His music is accessible to every human being, musically trained or not (provided he or she has a heartbeat). Before I got to know the complex but very seductive world of Wagner and his Tristan, there was Jeff Buckley. No other musician managed to cover my existential doubts as much as he did in the 1990s, to answer life questions that I couldn't even formulate and - with his music - made sure that I could face the things that happened in my life without having to numb myself. Thinking of Tristan, and the question of Erlösung, I can't help but think of the American singer-songwriter, who, with his dazzling voice and haunting songs, took the listener on a trip to a world far beyond ours. A world in which the listener expected to see his own solitude, only to find out with amazement that someone had been there before. Buckley brought the listener closer to themselves. His music escaped the delusion of everyday life, as if he felt that the salvation of worldly suffering was not something to be found within this earthly realm. Where the sound of killing guitar riffs and double bass drums from bands such as Metallica, Slayer and Death showed themselves to be good opiates for the sincerely uncertain feelings that had nestled in the body of yours truly, Jeff Buckley's music felt like an answer to essential questions. It is because of this genre-transgressing reference that this performance of Tristan und Isolde was of exceptional value to me. It rose above the exceptionally high level that Wagner productions of The Dutch National Opera already have. The opera here was not only the usual contagious mix of music drama and theatre - something that reminded me why I got addicted to Richard Wagner's music in the first place - but it was a Gesamtkunstwerk that contributed to an experience that contained everything that music means and has meant to me. With Wagner and Buckley the music may, at first eye (and ear), seem very different from each other but it has in common that it touches on the need to interpret profound uncertainties and give them a place. It is music that, if only because of the power of illusion, provides you with a partner. Both Wagner and Buckley were artists who were able to turn their personal demons into art that had universal expressiveness. When Jeff Buckley died (in 1997 he drowned at the age of 27 in Memphis, Tennessee), for me pop music died. Jeff Buckley was the last real musician in the pop scene, perhaps even a musician in the category of Jimi Hendrix. His art did not so much transcend genres as it simply did not care about the whole concept of genre. Jeff Buckley ruined me for everything that existed next to him and came after him: U2, Radiohead, Coldplay, the whole Britpop scene, I didn't need to hear it anymore and I never listened to it again until this very day. The death of Jeff Buckley was the sign that I had to look for something else. At places I did not consider before. Because although my interest in metal never completely vanished, it was also in that genre a long time ago that I had heard something that really surprised me. That the thing I was looking for would manifest itself on a stage in the Amsterdam Muziektheater in the form of an incestuous love affair between brother and sister I couldn't have envisioned by then. In 2001 I attended Die Walküre. A performance that would turn me into a Wagner aficionado. A hobby with the characteristics of an addiction. A condition that made my CD cabinet soon turn out to be too small because of all the existing Wagner operas I had to have different versions (of course). This is a problem of space shortage that has been going on until now because, despite the digital revolution, YouTube and streaming services, I have remained an old-fashioned CD buyer (who has to be careful not to pursue a complete Ring on vinyl in the near future). This Tristan brought back the Pierre Audi Ring and the time that preceded it. It surpassed, even more than usually with Wagner, the world of entertainment and became a catharsis. An experience that gave me a glimpse into my own soul and by doing so, cleared up and rearranged what has accumulated in the mind over time. - Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

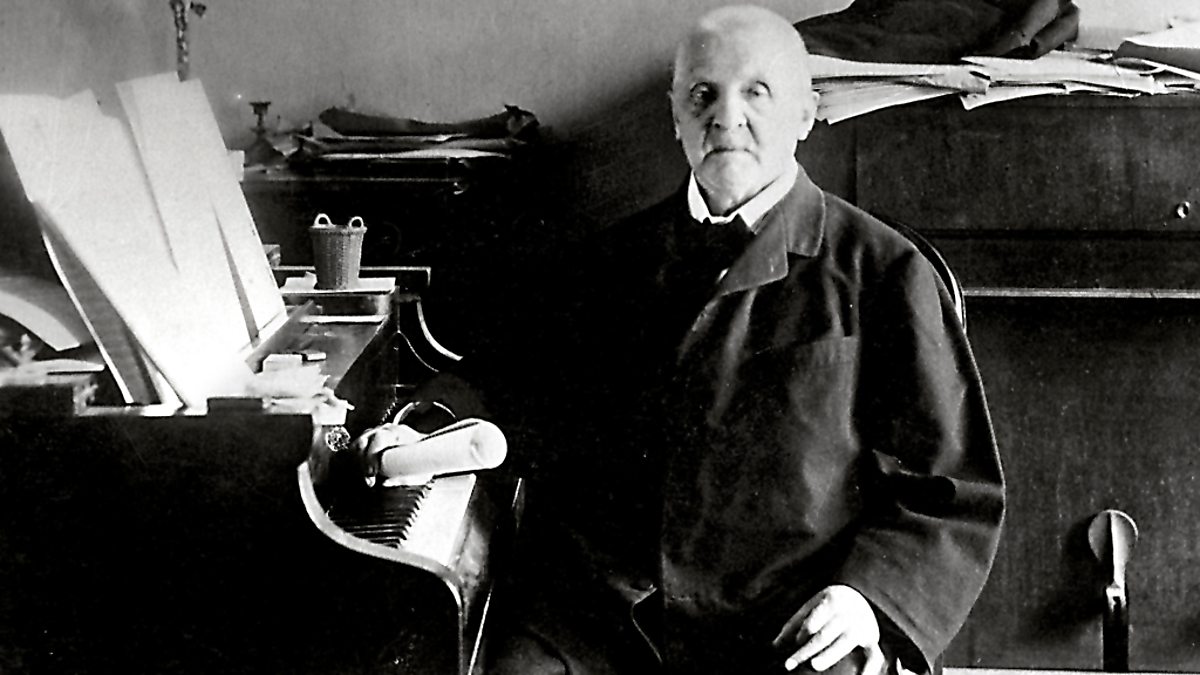

Bruckner's last symphony as the first concert of 2018 In search of the last, musical internalization with his maker, Anton Bruckner got stuck with a symphony that was short of a final. Only sketches of that final of his ninth symphony remain. How much Bruckner, if he would have had the time of life, would have changed, how that final eventually would have sounded, how much he would have changed in the three movements that he had already finished, remains a pretty wild guess. But it is very likely that he would have used the retouching pen. The Austrian composer, who was always in doubt about himself, tended to keep on working on his compositions long after they were initially finished. He had only just started the work on his ninth symphony (in 1887, nine years before his death) when Hermann Levi (the one from Parsifal’s premiere in Bayreuth) rejected the eighth symphony - the one Bruckner just had completed. Bruckner didn’t took this rejection lightly and during the process of composing his Ninth, he would revisit his first, third and eighth symphony. It may have cost him the time he needed at the end. At the time of Bruckner's death, the ninth symphony remained a torso. A torso that, despite missing a head, was voluptuous enough to serve as a complete work of art. In life and in the time immediately following his death Bruckner's music was only moderately appreciated. Bruckner's many critics in the Wiener music scene (Eduard Hanslick & Co) approached his music with indifference and hostility. At the posthumous premier in 1903, it seemed Bruckner's pupil Ferdinand Löwe wise to rid of the symphony from his sharp edges in order to enable it to find an entrance with the public at large. That plan succeeded and the Ninth became a success with press and public. In the 20th century, Anton Bruckner became an household name and Löwe's chastised arrangement for the Ninth is not heard much anymore in the concert halls nowadays. Sanitized versions are no longer necessary to make Bruckner acceptable to the general public. Bruckner 9 (edition: Ferdinand Löwe) With my affection for Richard Wagner's music - and the resulting stack of CD's and DVD's in mind - I have decided of Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, where Bruckner is concerned, as the alfa and omega of Bruckner recordings. Before the stack of Bruckner CD's reaches to the ceiling, I settle for Skrowaczewski's symphony cycle. Closer to the Bruckner-Valhalla one doesn’t need to come (and considering the time-consuming activity that goes at the expense of other composers it is perhaps even undesirable). For live performances of symphonies of the Austrian sound sculptor this is another matter. There, the search for something new continues unabated. There, performances that deviate from what I already know are reasons for extra joy. It is for this reason that I consider myself lucky with the fact that Daniele Gatti is chief conductor of the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra. For a long time Gatti has postponed the moment that he would venture to Bruckner. According to the Italian maestro, Bruckner's music can not be captured in an earthly narrative (like Mahler’s for example). The music takes place in a cosmic super dimension. At the concert of Sunday January 7th it was as if you could read from Gatti’s face the magnitude of the task that was awaiting him: to make sense – on an earthly stage – of Bruckner's super dimensional score. He looked very seriously. It even seemed like he did not like it at all. Music wise Daniele Gatti seldom failes to make a firm first impression and he did not fail to do that on Sunday either. He shrouded the Teutonic symphony in the dramatic robe of an Italian opera. With Gatti, Bruckner's reverence for God seemed to be mainly articulated by volume. It was, narrowing down on one aspect of this performance, a battle of the tuttis. His approach, marked by a stark sense for contrast, showed on one hand a keen ear for detail (after the massive tuttis the pizzicatos that followed sounded even more refined) with on the other hand a preference for large gestures that seemed to keep Bruckner away from the embrace with “Dem lieben Gott” that the Austrain composer-organ player must have envisioned. The original intentions of the composer aside: it worked. You had the feeling of attending an event (as often with Gatti). Despite that big plus, it remains difficult for me to qualify Gatti's interpretative qualities. With the undeniable awe for his reading of Bruckner’s Ninth, I wonder at the same time whether Gatti does not emphasize too much what is already obvious. One tend to think, for instance, that the crescendos are more than capable to tell their own story without turning them into a decibel fest. Gatti is not a painter who paints in thin strokes, he uses the brush, a paint sprayer even. He is an artist who emphatically demonstrates the rough edges that his approach leaves behind. It gave, despite or thanks to the finely tuned machine that is the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra, Bruckner by times an improvisational feel. As if the notes played had to be found on the spot. For the strings, Bruckner is hard work and with Gatti it is even harder work. With his approach, the conceptual virtuosity (the musically innovative) is explicitly accompanied by physical virtuosity (the ability to play difficult and complex music). With Gatti, the effort to transform a demanding score into a well sounding piece of music is audible (and visible). The orchestra sighed, creaked and burned. The bows of violin and double bass stayed, just by a small margin, safe from catching fire. The difference with the more objective approach in the Bruckner readings by Bernard Haitink (the natural counterpart of Gatti here) could hardly be bigger. Gatti gave Bruckner by times an improvisational feel. As if the notes played had to be found on the spot. However, apart from this high entertainment value, Gatti's approach does not seem to leave me with any new insights (like, for instance, Haitink and Boulez do in the Austro-German repertoire). Is Gatti in that respect perhaps a bit like Georg Solti? Like someone you don’t come back to after that first, impressive acquaintance? Time will (probably) tell. Gatti splits the minds of his audiences. You have people who stay and give the man a standing ovation and you have a (smaller) part of the audience that leaves immediately after the concert (as if they just witnessed something unpleasant, even vulgar, whilst probably thinking of Mariss Jansons in a nostalgic way). I do, despite the remarks I’ve just made, definitely belong to the first group. It was a Sunday afternoon full of Erlösungsbedürftigkeit. Both thematic and music wise, the link between Bruckner's last symphony ("Dem Liebe Gott") and the orchestral works from Wagner's last opera Parsifal ("Erlösung dem Erlöser") was a logical one. The orchestral pieces from Parsifal, the prelude of the third act and the Karfreitagszauber, were a special appetizer for a picnic (worthy of a copious diner) in the Carinthian Alps. After Wagner (proverbial) passed the baton on to his Austrian admirer after the intermission, it turned out how much the teacher's son from Ansfelden had been inspired by the sorcerer of Bayreuth. With Bruckner, the music becomes something cinematic, under Gatti's baton even more than Wagner's. By means of salacious strings and surging brass, Bruckner, the lifelong virgin, sounded remarkable lustful and potent. With a frantic Scherzo (played by Gatti without pause after the first movement) Bruckner continued his quest for the eternal that found its spiritualization in the Adagio. Thematically related to the Adagio from the eighth symphony, this quest came to an end with the announcement of a final which he was unable to complete in his lifetime. The concert ended with the last notes Anton Bruckner managed to make into a score - with a question that was missing an answer. In the deafening silence of that unanswered question we, the audience, were left behind. Knowing that we were granted an overwhelming glimpse into one the most impressive "Unvollendeten" in all of symphonic music. Concertgebouw 7 January 2018:

Koninklijk Concertgebouworkest Daniele Gatti - conductor Wagner - Prelude 3rd act ('Parsifal', WWV 111) Wagner - Karfreitagszauber ('Parsifal', WWV 111) Bruckner - Ninth Symphony in d 'Dem lieben Gott' |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed