|

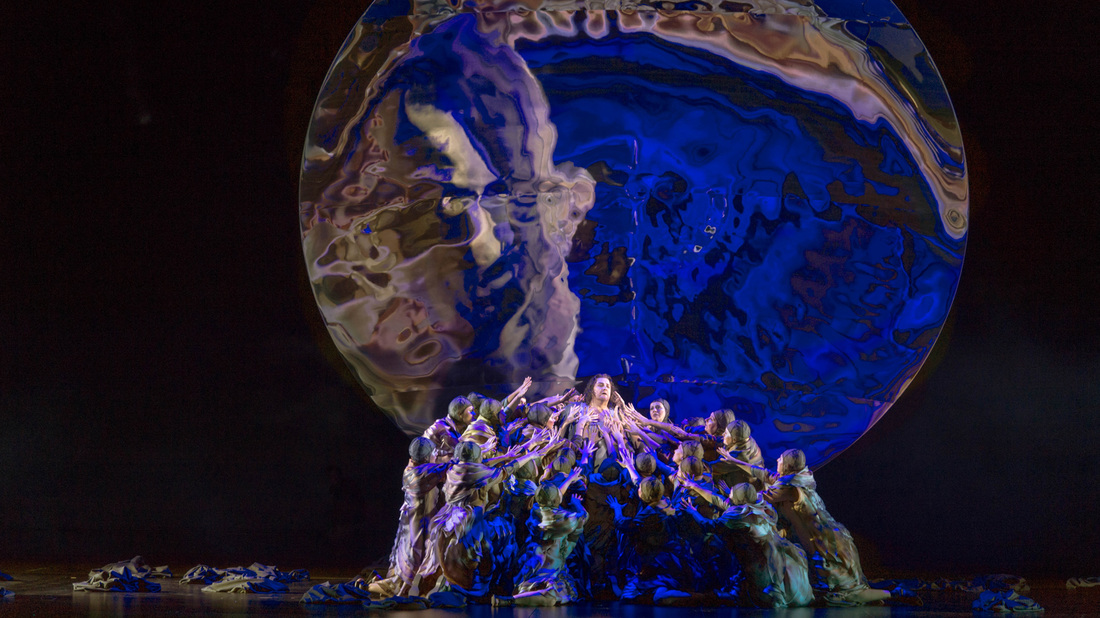

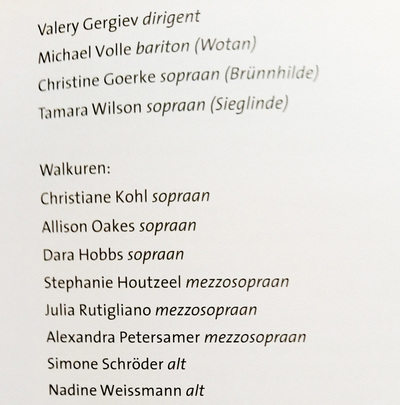

As the year ends we meet Parsifal. Wagner's most sacred opera, a Buhneweihfestpiel in which he emphatically puts the main themes in Christianity, salvation and compassion, up front. Away from the doom and gloom about the end of times and a sign of hope for an uncertain future. His last opera, composed with death in prospect, takes Richard Wagner to Montsalvant. The castle where Grail knights guarding the cup from which Christ drank at the Last Supper and in which his blood was collected when he hung at the cross. Parsifal, an opera that comes as close to an oratory as an opera probably can get, was initially only reserved for the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth. The use not to acclaim after the first act didn’t last to this day (it only lives on in the most obdurate Wagnerites) but it says something about the air of piety that for a long time surrounded the piece. Not in the last place because of its creator who explicitly presented Parsifal as an transformation opera. A piece that should help people becoming better versions of themselves. Wagner knew what he was talking about. His was a complex character with the ability to create great, complex art. A nucleus in which music, philosophy, religion and theater were coming together. Only Jesus Christ and Napoleon had more books written about them. In Parsifal one can see an opera that shows how rituals, emerged from the need for spiritual guidance and meaning, over time, can turn into dogma and corrupt whatever it is that once was pure and profound. Without the spirit from which rituals have emerged the only things that’s left are empty gestures. Parsifal sketches a world of spiritual decay. A world with Grail knights - paragons of chastity and surpressed instincts – that shows more than a few cracks. There are knights, quite a few, who fall for the temptations of the flower girls Klingsor, a magician with bad intentions (once he wanted to be a grail knight too - he even cut his balls off), has gathered around his castle. There is a king, Amfortas, who succumbed to the temptation of Kundry, and had to live with a wound, inflicted by Klingsor, that just will not heal. Kundry, some character too, taunted Jesus on his cloister to Golgotha and was sentenced to wander the world for eternity. A curse with a misogynist puff; it is her female seduction that make many a Grail knight apostate. Her suffering, and many a vampire story will endorse this, is the curse of the undead. The unability to die and therefore the impossibility to fulfill (and end) physical desires with an inevatible mental decline as a result. Ultimately a pure fool, Parsifal, is needed to jumpstart the whole thing. The hero who heals the wound of Amfortas by using the spear he wins back from Klingsor. He shows the Grail knights (and audiences) a glimpse of a future where the sun might shine. Christian symbolism aside, in all its multi-track interpretations, a recommendation for a faithful life Parsifal certainly is not. ... a spur to leave the protocols of organized religion ... There is room to see the opera as a spur to leave the protocols of organized religion and an urge to overcome what one has inherited from religion at home. To go back to the source. Not in manner but in spirit. Only then one can become a better person. On stage were crosses. Put together, sloppy and in error, illustrating a society in which the past is supposed to be understood but which ramshackle reproductions reveal that from that past and its original intentions only little knowledge is left (it bears a cynical resemblance, both in intention and outcome, to the failed attempts of American Nazis to draw a correct swastika). In Parsifal of the Dutch National Opera we are in a dark theater with stage designs of artist Anish Kapoor. Beautiful images with beautiful music, but a challenge to learn something about Parsifal, that the libretto did not tell us, it is not. Mirrors are kind of a Kapoor trademark (it should make him Klingsor's favorite interior designer) and Klingsor's magic mirror truely is magic here. The mirror in the second act, which comes back at the end of the third act as the Grail is revealed, delivers a collection of beautiful tableaux vivants - an invitation to enter the castle of Klingsor and the gardens that surround it. In the gardens there are flower maidens who are dangerously short of temptation. As often with Pierre Audi, the Regie is fairly abstract and rather sexless. Beautiful but a bit detached. Often Audi's productions are open ended. Meaning that they allow the audience space to interpret a piece of itself without distracting scenic images and additional storylines getting in the way of libretto and music. As a consequence of that the seduction in the libretto doesn't take shape on stage. For the temptation Wagner himself fell victim to when he met Carrie Pringle, we're basically left to our own imagination (Carrie Pringle was a flower maiden in Parsifal's premiere in 1882 in Bayreuth, the story goes that she and Wagner had an affair and her coming to Venice to see Wagner was met by Cosima with more than a few objections. In the quarrel that followed between Richard and Cosima, Wagner had a heart attack and died that same evening). I've attended the performance twice (December 9th and 18th). In both cases Petra Lang, the Kundry of service, was ill. She was replaced by both Alexandra Peter Amer (only the 9th) and Elena Pankratova (who sang the role last summer in Bayreuth). Pete Amer did so on the same night as her first of two performances as Walküre in an embodiment of the third act Walküre conducted by Gergiev in the Concertgebouw. She sang the part of Kundry in the first act (the Kundry for act two and three, Elena Pankratova, was still on the plane then). Both substitutes sang their part from the side while the role of Kundry on the scene was played by an actress (Astrid van den Akker). That saved the performance on the 9th from being canceled but it reduced Kundry to a bit of a ghost. The construction for Kundry (off-stage singing and on-stage acting) was maintained for the whole week. So a temporary solution became a permanent one. In an opera, that is not overflowing with action, and is directed by Pierre Audi, that can be considered a logical artistic choice. It stiffed, however, the confrontation between Parsifal and Kundry in the second act. In here Kundry was no more than a wraith, reduced to complete passiveness by the Regie. The Personenregie was, as often with Audi, marred by some parculiar choreographic manners. It seemed, for instance, to limit Bastiaan Everink (Klingsor) in his movements rather than to help him in portraying his role. The former elite soldier recognized, back from Iraq, in the music of Parsifal the real deal and made an impressive career switch to opera singer. He did, like the rest of the cast, an excellent job. From Ryan McKinny (who, besides advertising the gym, impressively beared Amfortas' sufferings with him) to Christopher Ventris, my introduction to him was on a DVD with the Nicolaus Lehnhoff production of Parsifal. Along with Waltraud Meier as Kundry, the best Kundry of this century. She doesn't do the big Wagner roles anymore but she was with her stage appearance and acting talent the incarnate desire of Wagner who preferred for his roles actors who could sing over singers who could act. (See the clip below. Kundry's comprehensive attempt to seduce Parsifal in the second act, a nice document of her superb acting and singing skills). Both orchestra and conductor Marc Albrecht were clearly out to impress. Albrecht's direction is massive, robust and swift. And he reintroduces the use of free bowing for the violins (for each player the moment of the draw of the bow is determined individually and not collectively) to create a fuller and lusher sound. It was like the second coming of Leopold Stokowksi. For the lover of Teutonic drama the weekend was best, submerging in a WagnerFest. A weekend that contained Parsifal on Friday and on Saturday a concert performance of Act III of Die Walküre. I was once acquainted with them through Apocalypse Now and Bugs Bunny; Valkyries (women stronger than men, half goddesses, Wotan's illegitimate offspring) which duty it is to deliver fallen warriors at Valhalla. Without helicopter sounds and Elmer Fudd chasing a rabbit - but with Valery Gergiev and the Concertgebouw Orchestra - I did put myself on a lavish Wagner meal in which the end of Die Walküre, after the five-hour Parsifal from a day earlier, served as dessert. Compared to Parsifal Die Walküre is more accessible. It's one of the doors through which I've stepped into the world of opera and classical music. Genre-transcending I would call it. You don't have to love opera to appreciate it. A bit like you do not have to be a lover of pop music to love Revolver and Sgt. Pepper of The Beatles and that you don't have to be a jazz cat to rank Kind of Blue of Miles Davis amongst your favorite records. Gergiev put on the fire that burns in Wagner's drama well. The Concertgebouw Orchestra was an organic machine in which all aspects of Wagner's music, from angry snarling anger to tear-jerking melancholy, had their place and where you, after the 70 minutes of the third act, never had the idea that the first two acts were sorely missed. Although it was a bit of a disadvantage. Because in a good performance of a Wagner opera, length is a force. A tool that provides maximum impact. It counts for Die Walküre, but also for Götterdämmerung and Parsifal. In the closing parts of these operas Wagner weaves titillating carpets of sound that makes the listener, even after more than four hours of opera, do yearn for more once it's over.

As an opera Parsifal is, compared to Die Walküre, a procession at angels pace. A place where space becomes time and where the daily rhythm is stretched into a long infinite melody that gives the listener moments that are like a concertina book that can be expanded to infinity. That is, together with salvation and compassion of Schopenhauerian cut, a fulfillment of basic human desires. It awards everyone, atheist and churchgoer alike, with a moment on the threshold of eternity. And so the year ends. A year that, for a large part, seemed to resonate with Götterdämmerung, with redemption and asceticism. Perhaps for the better. If only by the power of illusion, and if only for the duration of an opera we were safeguarded from nihilism and ill fate. It wasn't until days after attending my second performance that I realised how much the staging of the closing scene contradicted with the music. Where the music promised salvation we saw Grail Knights falling down, like Amfortas did earlier. With a stage full of bodies this was more salvation Jim Jones-style than the Erlösung Wagner granted us. His last opera took Richard Wagner to Montsalvant but this Audi-Kapoor production left us with Jonestown.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed