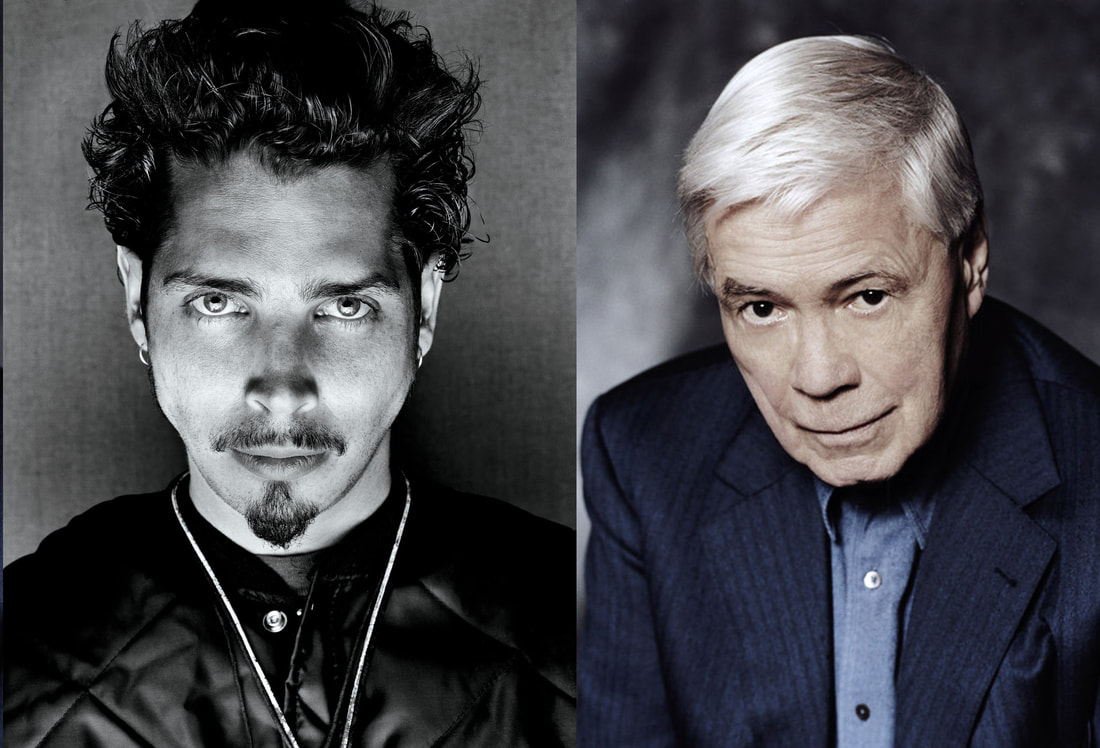

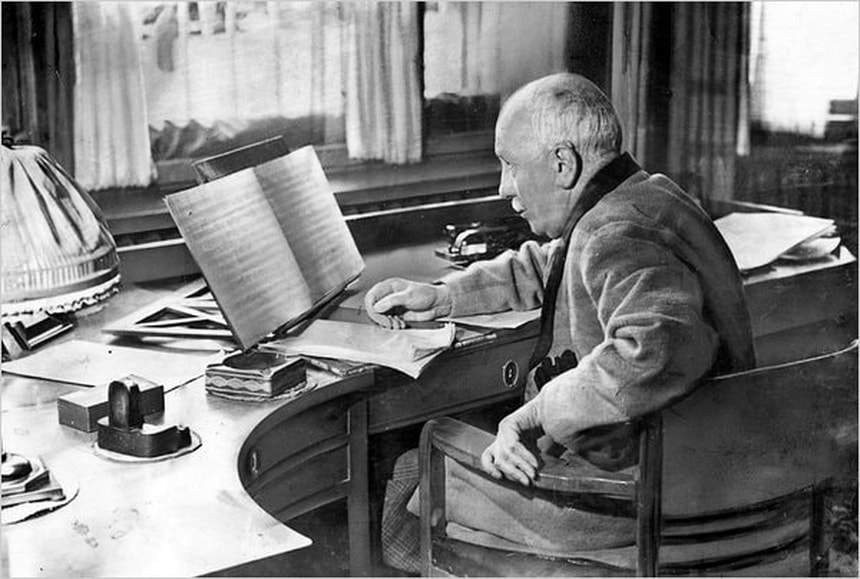

Gustav Mahler, Chris Cornell and Helmut Berger died on 18 May. That day is a bit the day of the dead. On 18 May 2023, Helmut Berger died. Perhaps his best performance was the title role in Visconti's Ludwig II, in which Berger gave a gripping portrait of the Märchenkönig: the king of Bavaria, maecenas of Richard Wagner, without whom there would have been no Ring des Nibelungen and no Festspielhaus in Bayreuth (see also this article). Helmut Berger is only one of many who died on 18 May. The day links the deaths of Gustav Mahler, Chris Cornell and others but we'll start with a birthday ... On 18 May 1883, Walter Gropius was born. On 18 May 1911, on Gropius' 28th birthday, the man with whose wife he had an affair with died. Gustav Mahler knew about Alma's affair with Gropius and his dismay at it he scribbled down in the margin of the score of his 10th symphony. Almschi! Für dich zu leben! Für dich zu sterben! Written with death in prospect and a wife who was unfaithful to him. The composer/conductor's mind was one that was in an overheated state in the last stage of his life. On his deathbed, Mahler had asked for a jar of ants to be placed next to the bed. The swarming of the little critters was supposed to distract his mind from the agony his body was going through. In founding Bauhaus, Walter Gropius wanted to pull architecture out of the realm of art so that it would focus on functional and accessible designs. You could call him the spiritual father of IKEA. More threads of destiny converge on 18 May. On that day in 1980, Ian Curtis hanged himself. Just before Joy Division was to leave for America for a tour and just before the band was to release its second album. The last film Curtis (you don't have to wait for death to tear us apart, love already does) watched was Werner Herzog's Stroszek. A film that premiered almost on 18 May (on 20 May 1977). Life apparently is extra hard on 18 May because on that day in 2017, Chris Cornell was found dead in a hotel room in Baltimore. He had just finished a gig with his band Soundgarden (their best record Badmotorfinger is a badass beneficial massage for eardrums and soul). It was at Gustav Mahler's special request that, after they would have determined death, they would stab him in the heart with a pen to prevent him from being buried alive. Being buried alive, a primal fear, especially in the pre-intensive care era, is a subject central to many a horror story and at least one song cycle. Lebendig Begraben is a song cycle written by Swiss composer Othmar Schoeck based on 14 poems by Gottfried Keller. The cycle depicts the thoughts of a man who is mistakenly buried alive after falling into a coma and being declared dead. And Dieter Fischer Dieskau, the legendary German Lieder Singer who died on 18 May 2012, gives one of his most impressive performances here (see clip in link). - Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

To commemorate the bombing of Rotterdam (on 14 May 1940), the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra is touring a number of places in the Netherlands with Gustav Mahler's 2nd symphony, visiting Amsterdam on 16 May, two days before Mahler's death anniversary. The city where Mahler himself conducted the Dutch premiere of this symphony in 1904. According to Stefan Zweig, art can make palpable what is crushed between the millstones of history. With the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra's performance, conducted by Lahav Shani, of Mahler's mighty second symphony, art seemed to aim to make sense of both the millstone and the crumbs. In a very confident reading, Shani led the Rotterdam orchestra along a journey of extreme moods: a traverse through deep valleys and euphoric heights. In what is perhaps the most operatic symphony in the repertoire, Shani opted for relatively slow tempi for the theatre of the second symphony (this was not a performance that would fit on one CD). Tempi with which he electrified moments and maximised expectations and which showed great insight into the architecture of the piece. On rare occasions, such as towards the end of the first movement, the slow tempi seemed to stall the journey, seemed to rob the music of its forward moving power, but that comment may be taken as splitting hairs in the context of this majestic performance. Mahler's Second is a symphony with strong contrasts between the movements, and in a good performance these contrasts complement each other, recognise in each other's differentness a kindred spirit. Mahler originally wrote a programme for his symphony but later omitted it. Within the context of this performance, the commemoration of the destruction of a city, and this symphony's nickname, Resurrection, music as ultra-powerful to the imagination as this one does not need a programme anyway. Little can match the hallucinatory powers of the brain as it searches for the personal images and feelings that the cathedral sounds of the Mahlerian orchestra evoke in it. At the crossroads where music and listener meet, a theatre of the mind is erected that no programme can do justice to. Despite the vast resources deployed, a large orchestra plus choir and solo singers, it is art that ultimately reveals itself to the listener in an extremely personal and intimate way. In Mahler's ingenious orchestration, in the details of the instrumental parts, the symphony is like a landscape in which the story of a life unfolds. Inseparable from life is death - the knowledge that time is limited is omnipresent in Mahler - and in his Second Symphony, Mahler sets himself nothing less than the goal of conquering death. The thundering percussion and raging strings created an irresistibly demonic atmosphere, with melodies cutting through the air like razor-sharp riffs. It was like a desperate opera of redemption. With those ambitions and pretensions in mind, it can be called remarkable that the text and music Mahler deploys speak to the listener in such a poignant way. Grand gestures that connect with intimate feelings, we love it at Wagner & Heavy Metal where we don't shy away from that irresistible mix of bombast and vulnerability. The form determines the content, the lyrics in the last two movements are a kind of religious tearjerker, but by piling up what would be clichés in the hands of lesser composers, Mahler, without falling into flat sentiment, rigs up an edifice that inspires awe and moves profoundly. It is up to performers to do justice to that brew of contradictions in a non-conflicting way, to leave nothing underexposed. The Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra and its conductor masterfully fulfilled that task. Everything fell exactly into place. Everything remained defined and audible. An orchestra that does not have its home base in the Concertgebouw might fall into the trap of playing too loud and muddle the sound. But none of that. Nothing was lost, from the softest passages to the fiercest eruptions of sound, the orchestral sound, even in the most forceful moments, remained transparent. The thundering percussion and raging strings created an irresistibly demonic atmosphere, with melodies cutting through the air like razor-sharp riffs. It was like a desperate opera of redemption, in which the composer and performers took us from the deepest caverns of the underworld to the inescapable climax where a divine, heavenly army resounded. That last movement, where orchestra and the fantastic Laurens Symphonic Choir forced the listener to awe and humility, was the perfect summation of all that had preceded it. One could only bow one's head in undergoing the passionately expressed desire to overcome what is inevitable for mere mortals, death. Grateful to have been present at a performance as lofty and majestic as this one. A performance in which you experienced music you know well (or think you know well) as if for the first time. And in essence, it was. The orchestra and conductor were improbably good, always in full control of the big lines and details in Mahler's tapestry of sound, so that what was unleashed on listening ears created the impression as if it could not have been done any other way. Thus, on the occasion of the commemoration of the bombing of Rotterdam, Mahler returned to the place where, since Willem Mengelberg started canonising his symphonies over a hundred years ago, he has never left (see box). And we are not done with him yet. Performances like this show time and again that there is little in the symphonic repertoire that can be compared with or stand up to the Austrian sound poet. It seems only inevitable that in the future, Mahler will continue to find new audiences. Willem Mengelsberg's role in music history is a story in itself. From a champion of Mahler's music (he called Mahler the Beethoven of our time) to a persona non grata who was kicked out of the country for being too close to the Germans during the occupation of the Netherlands.

During the German invasion of the Netherlands, and the bombing of Rotterdam, Willem Mengelberg, despite the threat of war, stayed in Germany where, in July 1940, he gave an unfortunate interview, to put it mildly, in which he seemed to approve, or at least downplay, the German occupation of the Netherlands. He is even said to have raised a glass to the Dutch capitulation there. From then on, Mengelberg would be seen as a country traitor and the Dutch would not forgive him his friendly dealings with the Nazis (he even accepted a Nazi ban on Mahler's work). Whereas German colleagues (such as Karajan & Furtwangler) could return to work after the war, after a process of denazification, all that remained for Mengelberg was a professional ban and exile. He would die in his Swiss chalet, Casa Mengelberg, on 22 May 1951 - on the 40th anniversary of Gustav Mahler's funeral. Mahler - Symfony nr. 2 in c 'Auferstehung', Concertgebouw Amsterdam 16 May 2023 Lahav Shani conductor Rotterdams Philharmonisch Orkest Laurens Symfonisch Chen Reiss soprano Anna Larsson mezzo-soprano - Wouter de Moor

Whether reflecting on the past in "Der Rosenkavalier", acknowledging the transitory nature of life in the career and music of Metallica, or the cycle of rise and fall in Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen, time is a central theme that reminds us that everything changes and passes.

The, on paper pretty bland story, turned out to be provided with sublime musical commentary by Strauss - full of irony, sarcasm and drama. Moreover, an engaging opera experience could do just fine without dystopian, murderous family relationships. There was life after Elektra, it turned out. And, suprise, the humorous moments turned out to be really funny. The action was perfectly tailored to the text and music. It turned the world of a pseudo-wig time that Strauss and Hofmanstahl had constructed into an electrifying universe. I needed a production like this to convert me to Der Rosenkavalier. Now, in revisiting this production by the Dutch National Opera, 8 years later, the machine of Personenregie appears to be less tightly tuned. Moments where I noted a smile 8 years ago, including the moment when Ochs is stabbed in the leg by Octavian, now go unnoticed. There is, of course, no substitute for the thrill that comes with the power of a discovery, and it’s logical that looking at the same production a second time, happens with a different, more seasoned, pair of eyes. But the regie lacks the finesse that made the earlier incarnation of this production so irresistible. Where the first time I made a triumphant Marx Brothers comparison (A Night At The Opera), this time, instead of humour, melancholy lingered the most. The wistfulness and wisdom of the Marschallin and the descending melody line that provides the sparkling love between Sophie and Octavian with a warning, an afterthought. Lost illusions of love lie ahead, the music seems to want to tell us. The trio at the end is one of heavenly beauty (it was played at Strauss' funeral in 1949). It is extra beautiful because that first gradually ascending melody in which the voices of Marschallin, Octavian and Sophie coincide is not repeated. At most, it is referred to, as much in Der Rosenkavalier's tapestry of sound is a web of references in which the repetition is never just the repetition. In a piece of music where repetition is used most successfully and effectively, repetition is never just the repetition. Our great friend Richard Wagner knew that. His leitmotifs are melodies and themes that recur, but the motifs that sound the same are slightly different each time due to instrumentation and context. They push you back and forth in a world of sound where you can refresh your mind and learn something about life, or even yourself. That endless flow of repeats and near-repeats into which, despite the unpleasant characters and dramatic events that often await you there, you are only too willing to vanish. The art of repetition. John Coltrane also knew how to do that. His sheets of sound are pregnant tapestries of notes that break down a wall, lift a spirit and crack a skull or two. His later work would inspire artists like Terry Riley and it is there, with American minimal music, where things go wrong. Themes on step-and-repeat. After a few minutes, you can go for a beer because there is nothing else to hear. The anticipation for the next note completely sacrificed to the form. As to why repetition sometimes works and sometimes doesn't, one could devote more than a few thoughts. Few things are, for example, as exciting as a repeating, searing metal riff. A powerful musical mean of awesomeness that can maximise expectations but also can lose momentum if, in the context of the bigger whole, it lacks the tension that continues to feed curiosity. I can't help but think of this when I hear the new Metallica. After 40 years in the music business, Metallica are where they need to be and that, along with the respect they earn for that, is also a bit of a problem. They don't have to prove anything anymore. From an underground extreme metal band, they have become a band that fills football stadiums, a band you go to see with the whole family. To object to the band's development over all those years is to object to the fact that they still exist and you don't want that. Metallica are the Marines of Metal, "the first one in and the last ones out" as Scott Ian once aptly said. And you can hate them, as you can hate the Rolling Stones, because they are so settled in the collective memory, because they are so ubiquitous. But when they are on tap, they can still sound irresistibly delicious as the previous full-length album Hardwired... to Self-Destruct with Spit Out The Bone and Lords of Summer proved. So every time the boys of Metallica come out with new material, we look forward to it. As a band, why make the same record over and over again? Why keep evolving as a composer? Richard Wagner could have seen in his third opera Rienzi a formula for success, a basis on which he could mould new operas. But his ambitions prevented that (fortunately). Keeping yourself from changing is perhaps only possible if you are Slayer, Motörhead or AC/DC. In that context, it might be nice to compare Slayer with Metallica for a moment. If you have to choose between Slayer's first album or Metallica's Kill 'Em All, you choose of course Show No Mercy. Slayer all the way. Where Metallica on Kill 'Em All still sounds like a beta-cross pollination of Motörhead and Diamond Head, Slayer is in Show No Mercy already everything that makes Slayer Slayer. Superhuman speeds on guitar and drums that together with Tom Arraya's screams merge into transcendental trash. Had Metallica made the same record 10 more times after Kill 'Em All it would have been nice for those who accuse the band of selling out for more than 30 years now but also nothing more than that. Point is, Metallica had to change after Kill 'Em All because they were not yet where they needed to be. And look what happens next. With Hell Awaits Slayer takes a next step, sure, but Metallica jumps into hyperspace with Ride The Lightning, the mother of sophomore albums. Trash at superhuman speeds with challenging chord progressions in an exhilarating kind of musical drama; Metal Mayhem in an Epic-as-Fuck kind of way. Trouble is though, as the rest of their discography demonstrates, you can only make such a leap once in your career. The moment Metallica got to Master of Puppets, which is perhaps a bit of an overrated album (correspondence about this can be sent to Wagner & Heavy Metal, address: unknown), they have been caught up by the ever-slaying Slayer, who, with their third album Reign In Blood reach the top of the Trashmetal-Everest. The second big leap Metallica made was after Justice For All ... but the Black Album was more of a commercial than a creative breakthrough. And Load was not a jump as well as a descend into murky waters. (Load was necessary to reinvent themselves, to break free from the stranglehold and expectations of a fanbase that had found the holy grail of heavy metal in their first three, or four albums. It was a record that was needed to get back to making music on their own terms but musically it was, well ...). Trash at superhuman speeds with challenging chord progressions in an exhilarating kind of musical drama; Metal Mayhem in an Epic-as-Fuck kind of way. And now there is 72 Seasons, the eleventh album from Metallica in 42 years. A new Metallica is an event just as the release of yet another new remastering of the Solti Ring is an event. An event where the fun is in the anticipation (often more than in the release itself). The songs on 72 Seasons sound a bit thrashier than on predecessor Hardwire, without breaking speed records, and one will search in vain for the epic headbutt-metal of their first four records. At times, thoughts turn to (the aforementioned) Load and Reload. Albums with a kind of metalised hard rock. Albums that have their moments (Until It Sleeps, included in the live set again this tour for the first time in 15 years, is a very underrated song) but albums that, with the best intentions on earth, one can't finish in one, uninterrupted, listening session. 72 Seasons suffers a bit from the same shortcoming. Lux Aeterna, the first single, sounds kind of like Motörhead, but without the dirt (it sounds more like a Lemmy tribute than Murder One on Hardwire was). The first three songs of the album, the title track, Shadows Follow, Screaming Suicide are quite good as individual tracks but with track 4, quite appropriately called Sleepwalk My Life Away, listening fatigue starts to set in. Then the shortcoming wreaks itself that the band regularly pushes its songs beyond their natural length. Then the repetitions in the songs end up in a dead spot. Sometimes it happens that what sounds boring on first listen starts to grow over time and becomes a haunting listening experience (Harvester of Sorrow on Justice ...), but whether that's going to happen here I seriously doubt. The band sounds like they have been economical with ideas. Kirk Hammett relies mainly on the pentatonic scale for his guitar solos but in trying to say more with less, the results sound somewhat laboured and the inventiveness and atmospheric, neo-classical intros and bridges of math Metallica are sorely missed. Longing for things lost in time ... This summer, for the first time in five years, I am going to Bayreuth again. Back to the theatre that Richard Wagner had built especially for the performance of the ultimate cycle of rise and fall, Der Ring des Nibelungen. Looking forward to it. To a new production of Parsifal in which time becomes a space in augmented reality. And Tannhäuser, Tobias Kratzer's fantastic production that was supposed to have its last run of performances this year but is prolonged due to success. But more on that later, no doubt. - Wouter de Moor

|

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed