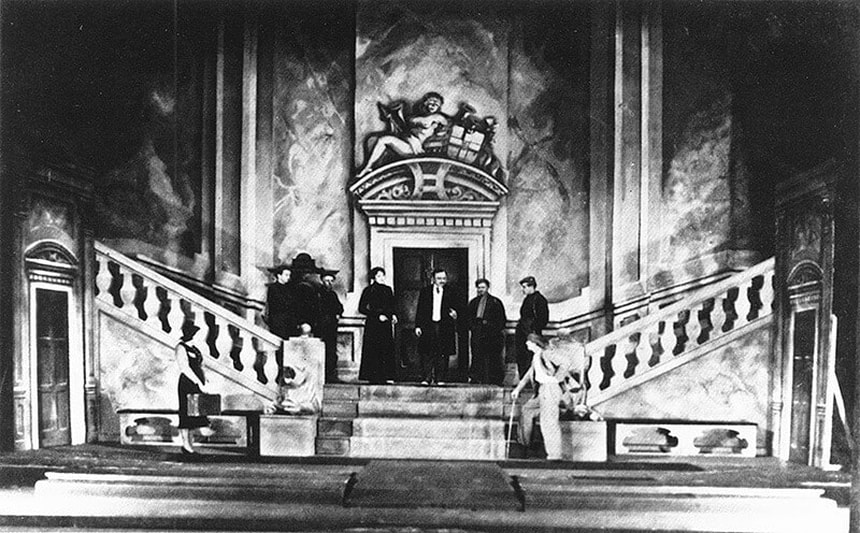

Opera Ballet Vlaanderen celebrates its return to the theatre with an exuberant production of Kurt Weill's DER SILBERSEE There was something to celebrate in Ghent last Saturday, when Opera Ballet Vlaanderen kicked off the new season in an almost sold-out hall with Kurt Weill's Singspiel DER SILBERSEE. After having seen its way onto the opera stage cut off for more than a year and a half by the pandemic and its related measures, the Belgian opera company once again presented a fully staged opera. Der Silbersee was the last piece Kurt Weill would make in Germany. After the Nazis had banned Der Silbersee from the stages, Weill first made his way to Paris and then to America, where he became an American citizen in 1943 and where he died in 1950. When Kurt Weill died, he knew no better than that the scores of Der Silbersee had not survived the book burning by the Nazis in 1933. That turned out not to be true, but Der Silbersee remains, to this day, a seldom-played piece. That is a pity because it contains beautiful pieces of music. In addition to Weill's well-known mix of classical music, cabaret, variety and jazz, the score contains choral singing that comments on the action and concludes the piece. It is an ending in which a chorus of ghosts accompanies the two protagonists, Olim and Severin, in their flight with a text that expresses hope. "Wer weiter muss, den trägt der Silbersee" (He who must go on will be carried by the Silver Lake). Both men are determined to drown themselves but, despite the sudden onset of Spring, the Silver Lake turns out to be frozen. It is an ending in which both men face a future that is uncertain but which suggests a spiritual redemption. Unlike, for instance, its predecessors Dreigroschenoper and Mahagony (which Weill created together with Bertold Brecht), it is not only the protest and the political satire that the audience is sent home with; the piece ends with a plea for humanity and hope. And the circumstances in which Der Silbersee was created played no small part in that. When Kurt Weill died, he knew no better than that the scores of Der Silbersee had not survived the book burning by the Nazis in 1933. When Der Silbersee was premiered in 1933, the Nazis had come to power just under three weeks earlier. The premiere took place simultaneously in three cities (this was not unique, in 1920, Korngold's Die Tote Stadt had its premiere in two cities simultaneously, but it was exceptional, a sign of Weill's popularity). Nationalism and anti-Semitism, which had been raging through the country for some time, found a perpetuation in Hitler's accession to the office of chancellor that would put an end to many things in Germany, the most basic decency to begin with, and one of the first victims of the Nazis' purge was the art that was considered un-nationalistic and cultural-bolshevik. In Der Silbersee, Weill and lyricist Georg Kaiser were unequivocal about the threat posed by the new authorities and their followers - they had very little compassion for people who had resorted to fascism as a solution to their problems. The Ballad of Caesar's Death from the second act, in which it's mentioned that Caesar wanted to rule with the sword but was killed by the knife, was with its direct reference to Hitler reason enough for Goebbels to pull the plug on the series of performances. After 16 shows, Der Silbersee disappeared from the stage.

The hunger, however, proves persistent and resurrects from the grave that was dug for him. The scene is interrupted, it becomes clear that we are watching a play in the rehearsal phase where, by way of trail & error, different concepts are being tried out. It is the starting point for the actors to regularly step out of their roles and where the boundary between the role they play, as actors in Der Silbersee, and the comments they make as "themselves", becomes diffuse. The science-fiction opening is followed by an actualisation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, we see the nouveaux riches as Egyptian pharaohs and there are references to Chinese opera. The "Ballad of Caesar's Death" from the second act, in which it is mentioned that Caesar wanted to rule with the sword but was killed by the knife, with its direct reference to Hitler, was reason enough for Goebbels to pull the plug on the series of performances. Der Silbersee is a story about social injustice, guilt, penance and forgiveness. Police officer Olim (Benny Claessens) shoots a thief, Severin. When it becomes clear that the thief has stolen only a pineapple, Olim's conscience starts to bother him. If only he had money, he sighs. It is fortunate that he then becomes the owner of a castle by winning a lottery. In the castle, he takes care of Severin; the relationship between the two is one of unrequited love. Severin does not know that it is Olim, the man who now claims to be his benefactor, who has crippled him. Severin (a strong role by Daniel Arnaldos) continues to seek revenge and Olim sees his efforts to heal Severin and seduce him into love, fail because Severin has built a wall of bitterness around himself. Meanwhile, Frau Von Luber (Elsie de Brauw), the former owner of the castle, tries to get her hands on the keys of the castle again with the help of her niece Fennimore. It is Fennimore who helps Severin reconcile with Olim when Serverin has found out that it was Olim who shot him, and she accompanies the two, we hear her voice along with the chorus, on their flight to the Silver Lake (a Parsifal-like ending with the promise of redemption, the chorus of prisoners from Beethoven's Fidelio also comes to mind). Fennimore is a fairy-like character who, in this production, is interpreted by two people: Marjan De Schutter in a talking role and soprano Hanne Roos. Mondtag places this new production in the year 2033, exactly one hundred years after the premiere of the original play. In this (future) world, an extreme right-wing party, The Iron Front, threatens to seize power. It threatens the production of Der Silbersee and splits the minds of those concerned how to deal with this threat. Mondtag is a man of exuberance, the carnivalesque and the cartoonesque, but also someone who tends to overplay his hand when it comes to proclaiming a message and then starts stating the obvious. Even without the trick of bringing the play up to date, of moving it to a future that mirrors the time of its premiere, the similarities between the present day and 1933, the time when Der Silbersee premiered, are strikingly clear. In a play where the music and songs are meticulously placed within the text by the composer, it would have saved a lot of (superfluous) dialogue if he had just limited himself to telling the original story. In a rarely performed piece like Der Silbersee, this would probably have been more logical. Mondtag's direction gives the actors a lot of space (too much space?) and Benny Claessens in particular grabs that freedom with both hands. That must have been premeditated. Claessens and Mondtag know each other well; they previously worked together at the German Gorki Theater where, among other things, they placed a version of Oscar Wilde's Salome in the same queer perspective as they do here. That queer perspective adds an extra layer that almost suffocates an already richly layered piece. The added texts, a part of them originating and based on actual texts from the creators' correspondence in 1933, are spoken in German, English and Dutch (languages between which Claessens switches impeccably). They might have benefited from a good edit for the progress of the play stagnates more than once. Brechtian alienation, actors stepping out of their roles, coincides with irritation about the carnivalesque cabaret that Der Silbersee lapses into from time to time. Cabaret that flattens the layering of the (political) seriousness of the lyrics and the multi-coloured music. The connection between the lyrics, that tell about hunger and oppression, and the music that mixes classical, cabaret, variety and jazz, makes the musical part of Der Silbersee of a stratification that is not adequately conveyed by the production. The cabaret to which the actors too often resort breaks right through the tension that has been so cautiously built up by Georg Kaiser's texts and the diversity of Weill's music. Music in which conductor Karel Deseure, in an inspired reading, full with expressive brass and pregnant percussion, holds all the various facets of the score together and pushes it forth with great forward-moving power. It is a parade of colourful (and noisy) characters who, in all their exuberance, set the tone of this production. An exuberance that connects more with the reality of being able to visit the theatre again than it does with the political fairytale of Der Silbersee. Thus, within the play of a play, this Silbersee became part of an even bigger play. The play that took place in the real world where a return to the theatre could (finally) be celebrated. A return to what was once normal, but never taken for granted because it was always special. It was a resurrection of the wonders of the living stage, place where we celebrate, relate, interpret and give meaning to life. The 2D of the streams of the past year and a half was exchanged for the 3D of theatre in flesh and blood. It was of a joy that surpassed the vivacity of the queer and camp on stage. DER SILBERSEE (Opera Ballet Vlaanderen) Dates: Ghent 18 sept, 21, 24 & 25 sept, Antwerp 3, 7, 10, 13 & 16 october Direction: Ersan Mondtag Conductor: Karel Deseure Severin: Daniel Arnaldos Olim: Benny Claessens Fennimore: Marjan De Schutter / Hanne Roos Frau von Luber: Elsie De Brauw Lottery agent & Baron Laur: James Kryshak - Wouter de Moor

2 Comments

An account of Parsifal in the church. Dutch director / bass-baritone Marc Pantus stages the third act of Parsifal in a place of grace. Wagner live! It happened after all in this Covid-year. A Wagner in flesh and blood. Wagner in a church with a chamber ensemble. "You have to do something", Marc Pantus must have thought, with the theatres closed in the last year and a half, and he made - a bit in the tradition of the St Matthew Passion that is performed every year in the Netherlands on and around Good Friday - a Parsifal for the church. In a special production came the third act of Wagner's last opera, already a kind of synthesis between a Passion and an opera, in an arrangement for chamber ensemble by Hugo Bouma. Not that you need to be reminded of it, of course, but what good, beautiful and layered music Parsifal is. A stratification in sound that remains effortlessly intact in an arrangement for piano, harmonium and synthesizer that, in the transformation scene, is assisted by four square gongs, a recording of the chorus from 1928 (by Karl Muck) and Kundry on bass (the latter not without a taste for the gimmick, it gives a momentarily band-vibe to the music). Three singers sing four roles, with initiator and bass-baritone Marc Pantus taking care of Gurnemanz and Amfortas, and Marcel Reijans singing (a superb) Parsifal. The whole thing is semi-staged, Parsifal in a nursing home. A place where people wait for death, for redemption. That salvation comes, when the grail is revealed. A moment when the lights go on and the Dominicus Church in Amsterdam proves itself to be the perfect setting for the Höchsten Heiles Wunder. In this environment, the question of whether Parsifal is a Christian opera or an opera that 'merely' uses Christian elements is almost more inevitable than usual, but we do not need the answer to that question in order to be fully immersed and to celebrate the return to 'Wagner in the flesh'. The last act of Parsifal is the last act of Richard Wagner's musical output. Death was already cautiously looking around the corner and Wagner hoped that time would allow him to finish his last opera, his Bühnenweihfestspiel. With Parsifal, Wagner has nothing more to prove; here, everything he had previously done is sublimated into the most subtle, beautiful music ever. With a special ear for the acoustics of his own Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, in Parsifal he allows the various instrumental groups to melt together, with melodies full of chromatic tension and dialectic delight flowing over an instrumental array of ambient and intoxicating sounds. A special role is reserved for the dissonances in the instrumentation, so crystalline brought to the surface in this chamber setting, which grants us a glimpse into the composition of Wagner's musical fabric; a sound carpet of unprecedented beauty that never ceases to fascinate. A music that distinguishes itself from a great deal of other music with epic ambitions that wants to be beautiful and outspoken, but forgets to be truly exciting in the process. After all, the ultimate result of something is the result of things that are not that result (I think somewhat pseudo-philosophically with 19th century sophistication). Parsifal, the opera about the pure fool who must bring redemption. As in Siegfried, ignorance is here a virtue that must unravel the knot of modern life or, better still, cut it rigorously. Parsifal is an opera about desire that must be suppressed. Here, giving in to lust, falling into sin, comes at a high price. It brings ruin to a community; it inflicts a wound that cannot be healed. Wagner has built an oeuvre on the search for Erlösung. The idea of redemption must have preoccupied him to a high degree, taking up a considerable amount of his time. When there is mention on the train of the Wagnerites' preference for Tristan und Isolde even over Parsifal, R. says: "Oh, what do they know? One might say that Kundry already experienced Isoldes Liebestod a hundred times in her various reincarnations."

That ending, when the grail is revealed, is accompanied by moistened eyes. It is a perfect soundtrack to the period of slowing down that the pandemic has forced us into. A period that with this Wagner production hopefully will come to an end. PARSIFAL, 3rd act (Dominicus Church, Amsterdam) Arrangement by Hugo Bouma Marc Pantus: Gurnemanz & Amfortas Marcel Reijans: Parsifal Merlijn Runia: Kundry + bass Daan Boertien: Piano Dirk Luijmes: Harmonium Andrea Friggi: Synthesizer & musical direction - Wouter de Moor

|

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed