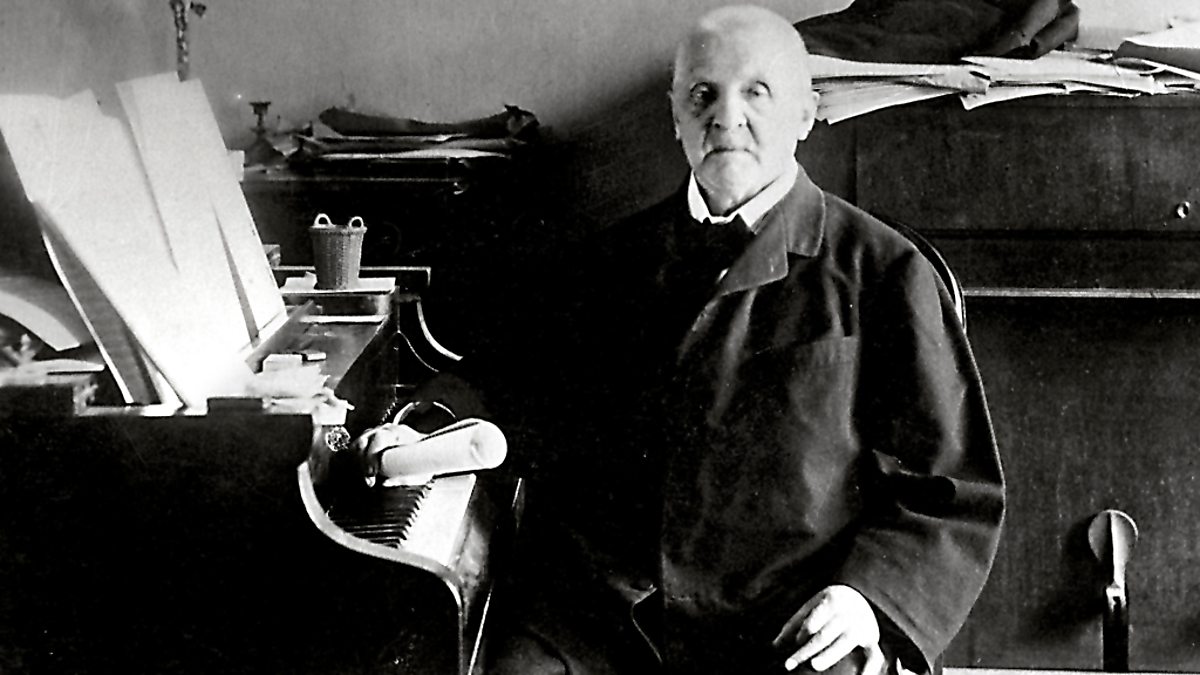

Bruckner's last symphony as the first concert of 2018 In search of the last, musical internalization with his maker, Anton Bruckner got stuck with a symphony that was short of a final. Only sketches of that final of his ninth symphony remain. How much Bruckner, if he would have had the time of life, would have changed, how that final eventually would have sounded, how much he would have changed in the three movements that he had already finished, remains a pretty wild guess. But it is very likely that he would have used the retouching pen. The Austrian composer, who was always in doubt about himself, tended to keep on working on his compositions long after they were initially finished. He had only just started the work on his ninth symphony (in 1887, nine years before his death) when Hermann Levi (the one from Parsifal’s premiere in Bayreuth) rejected the eighth symphony - the one Bruckner just had completed. Bruckner didn’t took this rejection lightly and during the process of composing his Ninth, he would revisit his first, third and eighth symphony. It may have cost him the time he needed at the end. At the time of Bruckner's death, the ninth symphony remained a torso. A torso that, despite missing a head, was voluptuous enough to serve as a complete work of art. In life and in the time immediately following his death Bruckner's music was only moderately appreciated. Bruckner's many critics in the Wiener music scene (Eduard Hanslick & Co) approached his music with indifference and hostility. At the posthumous premier in 1903, it seemed Bruckner's pupil Ferdinand Löwe wise to rid of the symphony from his sharp edges in order to enable it to find an entrance with the public at large. That plan succeeded and the Ninth became a success with press and public. In the 20th century, Anton Bruckner became an household name and Löwe's chastised arrangement for the Ninth is not heard much anymore in the concert halls nowadays. Sanitized versions are no longer necessary to make Bruckner acceptable to the general public. Bruckner 9 (edition: Ferdinand Löwe) With my affection for Richard Wagner's music - and the resulting stack of CD's and DVD's in mind - I have decided of Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, where Bruckner is concerned, as the alfa and omega of Bruckner recordings. Before the stack of Bruckner CD's reaches to the ceiling, I settle for Skrowaczewski's symphony cycle. Closer to the Bruckner-Valhalla one doesn’t need to come (and considering the time-consuming activity that goes at the expense of other composers it is perhaps even undesirable). For live performances of symphonies of the Austrian sound sculptor this is another matter. There, the search for something new continues unabated. There, performances that deviate from what I already know are reasons for extra joy. It is for this reason that I consider myself lucky with the fact that Daniele Gatti is chief conductor of the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra. For a long time Gatti has postponed the moment that he would venture to Bruckner. According to the Italian maestro, Bruckner's music can not be captured in an earthly narrative (like Mahler’s for example). The music takes place in a cosmic super dimension. At the concert of Sunday January 7th it was as if you could read from Gatti’s face the magnitude of the task that was awaiting him: to make sense – on an earthly stage – of Bruckner's super dimensional score. He looked very seriously. It even seemed like he did not like it at all. Music wise Daniele Gatti seldom failes to make a firm first impression and he did not fail to do that on Sunday either. He shrouded the Teutonic symphony in the dramatic robe of an Italian opera. With Gatti, Bruckner's reverence for God seemed to be mainly articulated by volume. It was, narrowing down on one aspect of this performance, a battle of the tuttis. His approach, marked by a stark sense for contrast, showed on one hand a keen ear for detail (after the massive tuttis the pizzicatos that followed sounded even more refined) with on the other hand a preference for large gestures that seemed to keep Bruckner away from the embrace with “Dem lieben Gott” that the Austrain composer-organ player must have envisioned. The original intentions of the composer aside: it worked. You had the feeling of attending an event (as often with Gatti). Despite that big plus, it remains difficult for me to qualify Gatti's interpretative qualities. With the undeniable awe for his reading of Bruckner’s Ninth, I wonder at the same time whether Gatti does not emphasize too much what is already obvious. One tend to think, for instance, that the crescendos are more than capable to tell their own story without turning them into a decibel fest. Gatti is not a painter who paints in thin strokes, he uses the brush, a paint sprayer even. He is an artist who emphatically demonstrates the rough edges that his approach leaves behind. It gave, despite or thanks to the finely tuned machine that is the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra, Bruckner by times an improvisational feel. As if the notes played had to be found on the spot. For the strings, Bruckner is hard work and with Gatti it is even harder work. With his approach, the conceptual virtuosity (the musically innovative) is explicitly accompanied by physical virtuosity (the ability to play difficult and complex music). With Gatti, the effort to transform a demanding score into a well sounding piece of music is audible (and visible). The orchestra sighed, creaked and burned. The bows of violin and double bass stayed, just by a small margin, safe from catching fire. The difference with the more objective approach in the Bruckner readings by Bernard Haitink (the natural counterpart of Gatti here) could hardly be bigger. Gatti gave Bruckner by times an improvisational feel. As if the notes played had to be found on the spot. However, apart from this high entertainment value, Gatti's approach does not seem to leave me with any new insights (like, for instance, Haitink and Boulez do in the Austro-German repertoire). Is Gatti in that respect perhaps a bit like Georg Solti? Like someone you don’t come back to after that first, impressive acquaintance? Time will (probably) tell. Gatti splits the minds of his audiences. You have people who stay and give the man a standing ovation and you have a (smaller) part of the audience that leaves immediately after the concert (as if they just witnessed something unpleasant, even vulgar, whilst probably thinking of Mariss Jansons in a nostalgic way). I do, despite the remarks I’ve just made, definitely belong to the first group. It was a Sunday afternoon full of Erlösungsbedürftigkeit. Both thematic and music wise, the link between Bruckner's last symphony ("Dem Liebe Gott") and the orchestral works from Wagner's last opera Parsifal ("Erlösung dem Erlöser") was a logical one. The orchestral pieces from Parsifal, the prelude of the third act and the Karfreitagszauber, were a special appetizer for a picnic (worthy of a copious diner) in the Carinthian Alps. After Wagner (proverbial) passed the baton on to his Austrian admirer after the intermission, it turned out how much the teacher's son from Ansfelden had been inspired by the sorcerer of Bayreuth. With Bruckner, the music becomes something cinematic, under Gatti's baton even more than Wagner's. By means of salacious strings and surging brass, Bruckner, the lifelong virgin, sounded remarkable lustful and potent. With a frantic Scherzo (played by Gatti without pause after the first movement) Bruckner continued his quest for the eternal that found its spiritualization in the Adagio. Thematically related to the Adagio from the eighth symphony, this quest came to an end with the announcement of a final which he was unable to complete in his lifetime. The concert ended with the last notes Anton Bruckner managed to make into a score - with a question that was missing an answer. In the deafening silence of that unanswered question we, the audience, were left behind. Knowing that we were granted an overwhelming glimpse into one the most impressive "Unvollendeten" in all of symphonic music. Concertgebouw 7 January 2018:

Koninklijk Concertgebouworkest Daniele Gatti - conductor Wagner - Prelude 3rd act ('Parsifal', WWV 111) Wagner - Karfreitagszauber ('Parsifal', WWV 111) Bruckner - Ninth Symphony in d 'Dem lieben Gott'

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed