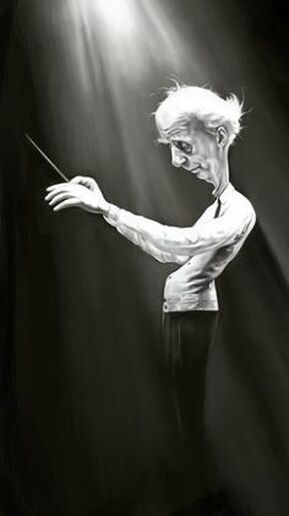

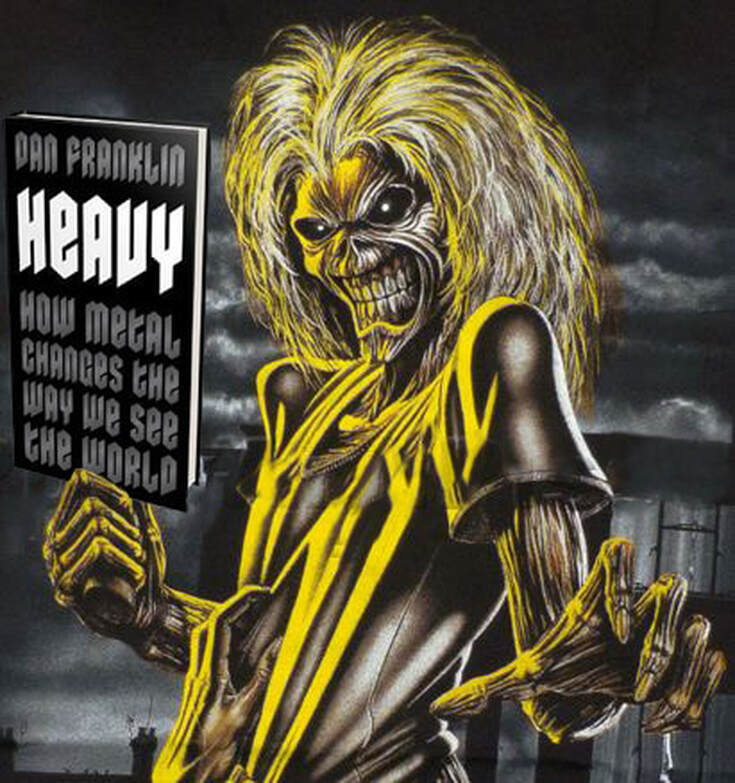

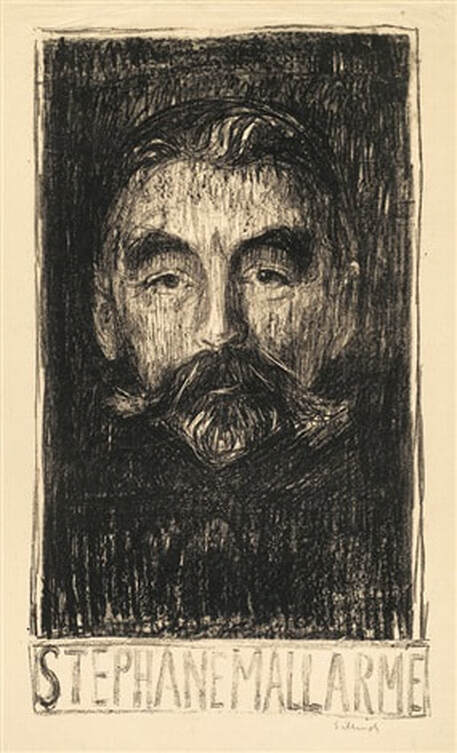

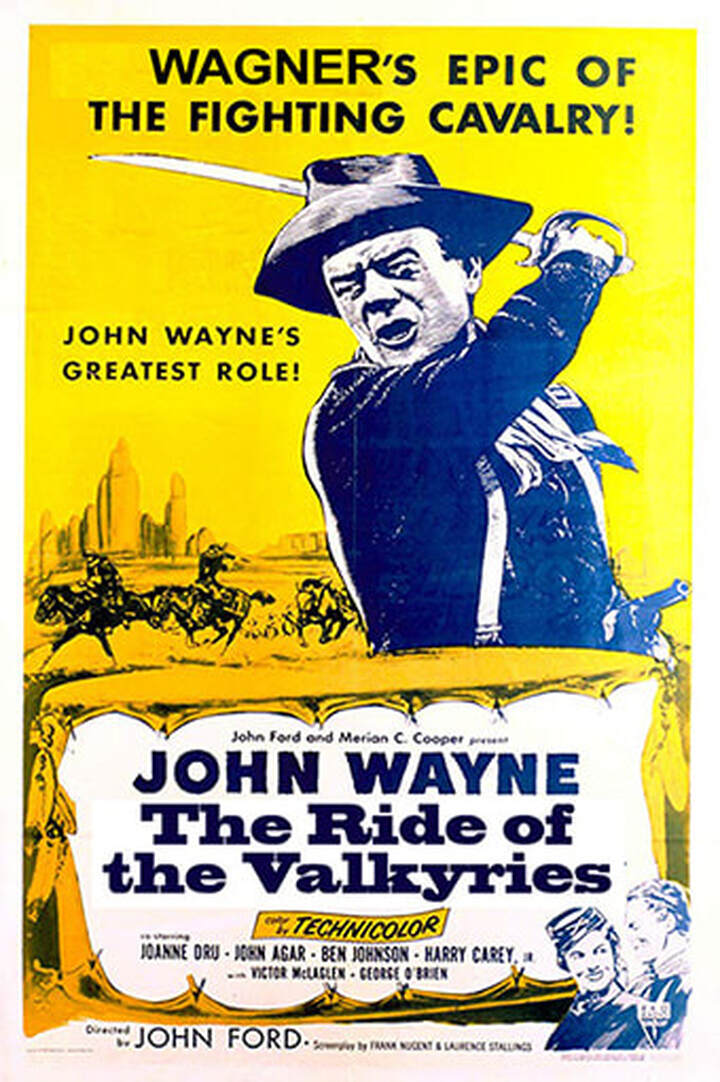

The WAGNER & HEAVY METAL WINTER WEBLOG on music, books and the light at the end of tunnel. From ' HEAVY' (Dan Franklin) to a heavy book 'WAGNERISM' (Alex Ross). Plus Wilhelm Furtwängler and (a lot) more. Reading time: 17 minutes It was March, a bat in Wuhan had the world locked down, and I dreamt that I walked into a large building, gothic in design, in which there were countless cases with books. I was in what must have been Borges’ idea of heaven: a large, infinite library where you can fill your head with what people, in their most sublime and intimate thoughts, had written down. At first the library was everything I could wish for, I devoured one book after another, but after a while (could have been years or centuries, dreamtime is hard to define) I noticed that the books no longer spoke to me. I was exhausted and empty. I filled my head but my body didn't follow anymore. Isolated from the outside world I had become a stranger to my own feelings. I could no longer relate to the events and emotions I read about in the books; I had nothing more to add to them. I, the introvert, needed the outside world to keep the mind oxygenated. Life needs maintenance, so the dream seemed to want to warn me at the beginning of the lockdown. While summer has turned into the grey, cloudy autumn and the blackened agenda of recent months (no MahlerFest, Bayreuth and much more) lies still heavy on the mind, we again, at least for a while, go into lockdown. Once again the road to the concert hall is being cut off and once again the man who is no stranger to spending time on the couch with books and music sees the new time with new unease. Will they all still be there when all this is over? The halls and theatres where we can attend concerts and operas? For me the ban on visiting concerts was recently broken by a chamber orchestra performance of Gustav Mahler's Fourth symphony. It was a Covid-concert - 12 men in the orchestra instead of 100, the hall filled for about 1/3rd, and a programme, in which Mahler shared the programme with Alban Berg (Sieben Frühe Lieder), that was played twice. Soprano of service was Barbara Hannigan. I gladly gave up my reservations against coming together in confined spaces during times of Covid. The return to the concert hall was special. An occasion where the music testified that everything of value is ultimately more vulnerable than you would like to think. It was remarkable (and kind of funny) that the performance by a chamber orchestra of a symphony written for large orchestra bore in it the sense of improvisation that synchronized with the character of the concert (making the best of a situation). No preoccupations with things like tempi and the ideal balance of instruments. More than listening to a piece of music you know from your preferred (recorded) renditions, it was like listening to your favourite band performing in an unplugged session. Mahler’s Himmlische Leben, the heavenly life, was, as expected, in joyful, glowing hands of Hannigan. But it was the Adagio, initiated by a cello, full of bromide and brooding desire, that was exceptional. It built a bridge between two worlds; a bridge between the world during and the world before the pandemic. The Adagio connected with the last concert I visited before the lockdown: Mahler's 9th symphony in February. You don’t have to hear a premonition of death in the Adagio of that symphony, six months later it acquired nevertheless the depth of a farewell for me (Stephen Johnson argues in his book "Symphony of a Thousand: Mahler and the World in 1910" convincingly that this is not Mahler's farewell to the world and makes, even more than he does for the 8th, a case for the 10th symphony). The dissonants of the Fourth, a beauty not yet complety smoothened, rubbed against the dissonants of the Ninth. The sound of the cello cast a glance on the world of yesterday. A world of which you could not imagine it would ever be exchanged for another. With the relative lightness of the Fourth, the tragedy of the Ninth became even more poignant, once again palpable; it was the symphony that the composer was never able to hear in life. The time to deal with matters of eternity is limited for everyone. (And then, while writing this blog post, I heard that Eddie van Halen had died. Stunning silence).  Mahler, the name on the bill was like a leitmotif. An indication for drama with which one purifies heart and soul. Mahler as a leitmotif, a word with gravitas; a pointer for feelings that directed me back to the concert hall. My late father found Mahler scary. He identified him with Romanticism, the macabre side of it. Who writes something like Kindertotenlieder? It kept him away from the German/Austrian Romantics until, late in life, he heard Lohengrin and concluded that he had apparently missed something of indelible beauty. In 1904 Mahler completed Die Kindertotenlieder (songs on texts by Friedrich Rückert about the death of young children) - it was for Alma like provocating fate. Four years later their daughter Maria died. In the long life that would have befallen her (she would die in 1964, she would survive Mahler longer, 53 years, than Mahler had become old), Alma Mahler never wanted to hear Die Kindertotenlieder. With Skeleton Tree from 2015, Nick Cave wrote a kind of his own Kindertotenlieder. It's an album with lyrics about loss and death that seem to creepily precede the death of his own child. (When the recordings for the album were almost finished, Cave's 15-year-old son, Arthur, fell off a cliff). In HEAVY, the book in which Dan Franklin shines his light on matters of gravitas in the world, the name Nick Cave is mentioned by Phil Anselmo, former front man of metal band Pantera. His journey along the fringes of existence brings Anselmo alongside extensive drug abuse to the art he considers substantial – ‘heavy’ if you like and Nick Cave is as heavy as one can imagine. Just as a lowering of the tempo does not automatically mean that music becomes more dramatic (the thoughts almost automatically go out to Reginald Goodall's Parsifal, the only Wagner recording in my possession that I can't get through), decibels are no guarantee for heaviness. Heavy is in the character, in the intention, in the source of where the music comes from. Heavy is the foundation on which indefinable feelings find solid ground. There is certainly a physical aspect to Heavy where overdrive guitars and rolling bass drums can come in handy but Heavy doesn't forget to connect large gestures with intimate feelings. Heavy has a feeling for theatre and Heavy knows that drama can't do without beauty. (Yes, opera is heavy). Heavy absorbs the punches, is an airbag for the blows inflicted by life. Heavy turns that which one feels insecure or ashamed of into a fist with which one can attack the world. Heavy is the joy that lurks in a minor chord, the profound pleasure that comes from listening to gloomy sounds and discovering that you are up to it. Heavy is, above all, of course subjective. Dan Franklin's search for it is a personal one and that's what makes it so much fun. It's a quest that triggers one's own. In his search for what is heavy, Franklin crosses over from music to literature and film. Whereas Schopenhauer once said that you should be able to buy with a book the time to read it, with a book like HEAVY, which derives its reading power from a multitude of references that makes you Google while reading, you wish you could get that time as an infinitely extendible leporello. Reading HEAVY is like playing chess on several boards simultaneously with a recurring sense of shortcoming. (For why have I not yet seen Zabriskie Point by Michelangelo Antonioni?) Striking is the distinction Franklin makes in HEAVY between real heaviness and cosmetic heaviness. Nirvana is heavy, Limp Bizkit is not. The difference seems to speak for itself. The authenthic scream of Kurt Cobain that exorcises existential fears, as opposed to the band of Fred Durst who sees in their (derivative) nu-metal mainly an instrument for scoring girls (although a song like ‘Nookie’ comes from dealing with heart ache, the overcoming of the position of a underdog, its pose and triumphantness deprives it of any form of sympathy one might consider). After Nirvana crushed the plastic pop music and the glammetal of the 80's to pieces (eternal gratitude for that!) many a rockstar jumped on the bandwagon of the grunge. With grunge the focus turned inwards, rock music became more introverted. Grunge gave (hard)rock a new dark elan of heaviness (and Badmotorfinger of Soundgarden was the most heavy thing around; it was even more than Nirvana’s Nevermind, that had a remarkable universal appeal to the public at large, an album that separated heaviness from would-be heaviness). Instead of ‘just’ superficially chasing girls, the lyrics in grunge were about 'real' feelings. Many a glam rocker dressed up in a lumberjack blouse. Mike Tramp from White Lion turned to the 'dark' side (with Freak of Nature) and he wasn't the only one. Where in many a transformation from glam to grunge the commercial motifs were at display, the distinction between true heaviness and cosmetic heaviness (as a distinction between being sincere or not) was not always as obvious as first impressions suggest. Both Pantera and Alice in Chains had a hairmetal past and their exchange of hairspray for lumberjack check shirts might suggest, aside for creative motifs, a concern for the cosmetic (and commercial). Further on: WAGNERISM, what Mike Patton has in common with the French Symbolists and Wilhelm Furtwängler in Italy >> Who also had commercial motives when he composed one of the heaviest, most important operas in music history was Richard Wagner. Shy of money, as always, Wagner had an opera in mind that should be easy to produce. It turned out somewhat different for Tristan und Isolde. The line-up could be limited to two protagonists and a few supporting roles, the vocal demands, however, proved considerable. The potential places for the premiere, including Rio, Strasbourg, Paris and Vienna, all dropped out (70 rehearsals were needed in Vienna, but the singer for Tristan did not get his role learned). Not until 5 years after completing the opera the premiere took place in Munich (in 1865). Wagner initially had imagined Tristan for Paris, the cultural capital of the world, but after the disastrous performances of Tannhäuser in 1861 he abandoned that idea. He would no longer live to see his name established in the French City of Light, but his influence, posthumously, on French cultural life, especially literature, would become considerable. The French may not have loved him immediately, in the end they understood him like no other. The French Symbolists stretched their words where the music and libretti, their melody, timbre, color and rhythm, of Wagner had challenged them to. Mallarmé envisioned “a poetry that imitates music, surpasses it, and stages in the theater of the mind the higher drama that Wagner sought in vain.” It is one of the many examples in WAGNERISM; a marvel of a book in which Alex Ross explores Wagner's influence beyond the boundaries of music. What a text means and to what extend a text speaks are not the same thing. A meaningful text is something other than an expressive text. An intriguing part of the lyrics of Mike Patton (Faith No More, Mr. Bungle, Fantomas) is that the words are chosen for their sound as much, if not more, for their literal meaning. The words become, through their sound, an integral part of the music. It is not so much a text that is set to music, but setting sound itself. The message, eventually, is in the sound. According to Christiaan Thielemann that is one of the differences between Italian opera (in which words are set to music) and the German Wagner opera (in which Wagner is setting sound itself). Where for instance Verdi (and his librettist Boito) are cutting, distilling and dramatizing – Wagner is letting the sound flow. Back to that very first revelation in which I recognized in Wagner's music an old friend I had never known. In that music I recognised the classical music that my father used to play (Beethoven), but I heard that Wagner had modernised that music - stripped it of classical form - with an instant addictive effect. I couldn't explain it musically-theoretically, I didn't have to do so in order to surrender to it. It sounded like a confirmation of my inner self. A discovery of something that was not so much out there but a window I opened in myself. And it was as if Wagner made it clear to me that I could rely on my own feelings. That I could trust my instincts. A confirmation (if ever I needed one) that meant the world to me. Wagners' music was reminiscent of film music, it was music with great visual power. The first time I heard Die Walküre (a CD with a studio recording from 1962 led by Erich Leinsdorf with Birgit Nilsson and Jon Vickers) I didn't know what it was about, but a film passed me by. Later, when I checked in with the story and libretto, I didn't need a staging to imagine the story. When Wilhelm Furtwängler had completed the studio recording for EMI of Tristan und Isolde in 1952, he expressed the idea that Wagner's operas might thrive best in concert performances. He knew he was contradicting Wagner, but Furtwängler came to the conclusion that theatrical images only distracted audiences from the musical splendour and power in which, after all, everything was already incorporated. (Although that works differently for each individual. Director of The Last Jedi, Rian Johnson, told in a conversation with Alex Ross that Wagner's music only started to work for him after he had seen a Ring cycle in the theatre; he needed the images to comprehend the music). It was a long summer that now, with increasingly darker days, seems to have past so fast. I listened, for the first time in its entirely, to the RAI 1953 Ring under Furtwängler. I couldn't put my mind to it sooner, give it the attention it deserved. The RAI Ring is widely praised, it is Christiaan Thielemann's favourite Ring recording, but until now, despite the combination of Furtwängler and Wagner, it did not strike me as essential. The Ring that Furtwängler recorded in La Scala with Kirsten Flagstad as Brünnhilde was sufficient for me when it came to Furtwängler and the Ring cycle. Recorded live in 1950, this Ring has drama, theatre and depth. We experience a sultry winter storm with Günther Treptow & Hilde Konetzni as Siegmund & Sieglinde. Treptow is a powerful Siegmund who is not afraid to show his feelings - as befits a real man. The scene in which his Siegmund expresses to Brünnhilde that he prefers earthly love (in dire circumstances) with Sieglinde to a paradise life in the Walhalla cuts through the soul. Under Furtwängler's majestic handling of the large arches in the score flows smouldering magma. And Flagstad's Immolation scene makes me longing - despite a heartfelt ‘be careful what you wish for’ in these times of turmoil - for the end of the world. How Furtwängler heard and interpreted a composer remains an almost inexhaustible source of fascination. I am thinking of his performances of the symphonies of Brahms. Symphonies in which Furtwängler brings out an unprecedented energy and demonic power where, characteristic for him, especially in his live performances, he exchanges beauty of sound for romantic expression (probably not quite how Brahms himself must have had in mind). Musical phrases entrusted to gravity and time with a seemingly anarchistic slant. As if you push a container of boulders off the hill and, in the noise that follows, recognize a pattern that, as in a fractal, allows itself repeatingly to be dissected to a next level of smaller details. The result is breathtaking. It is Furtwängler who in no small way made Brahms and Tchaikovsy (his 1938 Pathetique!) accessible for me. Unfortunately, there is no Ring recording of him that in this way combines power, expression and drama (it remains to be hoped that a complete pre-Second World War Ring cycle recording from London will surface one day, it seems to exist).  The RAI Ring relates to the Scala Ring as a studio recording to a live recording. This Ring is recorded, one act at the time, for radio recordings with an audience that only reveils its presence by applauding at the end of each act. The RAI Ring is especially interesting for the singers. Compared to the Scala Ring, the RAI set-up gives them more space and they need less to compete with the orchestra. That orchestra sounds a bit stiff. Especially if you compare it to the Scala Ring and particularly if you put it next to the Ring that was recorded in Bayreuth that same year under Clemens Krauss. Furtwängler saw Hans Richter conducting Die Meistersinger in Bayreuth in 1912, and that performance stayed with him as his ideal opera performance. It was an opera like a conversation piece, a performance in which you forgot the music. Listening to the RAI Ring, you cannot escape the idea that Furtwängler extracts his own vision of the Ring, of Wagner, to a large extent from those performances under Richter, and successfully conveys that vison to orchestra and singers. Because of a struggling Italian orchestra, at times it is as they are still rehearsing the score, Furtwängler has to keep things audibly on track from time to time; it is indeed more of a conversation piece than hot-blooded drama. Eventually, the intoxication is no less; once descended into Nibelheim, it won't let go. Martha Mödl is a great involved Brünnhilde (she brings more drama to the role than Flagstad) and Ferdinand Frantz is a robust Wotan (he fits the Wotan that Furtwängler must have envisioned better than Hans Hotter, who was more lyrical). Julius Patzak's Mime, a key role in the whole drama, is a disappointment; he sounds more like an office clerk than an intriguer who tries to gain access to the Ring via Siegfried. Furtwängler came to Wagner a bit later in his professional life. As a teenager he thought of the Ring as just a superficial piece of musical theatre with an oversentimental libretto that lacked a heart, a human touch. It was an attitude that would change, but with Das Rheingold Furtwängler kept his reservations. He felt that this opera of the Ring was the most difficult to bring to life for the audience. In the RAI Rheingold these objections become tangible. The orchestra under Furtwängler rises a bit slow (literally) to the occassion and it is eventually not until Götterdämmerung that it blends in with the master's vision. But even then it doesn't really get to the underlying drama. We are never given a look at the primal forces that control the world. It is true that a fascinating story is being told here, with strings that turn to gods, man and fate with demonic pranks, but it remains a bit of a stiff excercise in which drama and expression remain stuck in a somewhat rigid presentation of music and text. It's a meal that at times is spicy but the salt and pepper in the playing of the orchestra never turns into musical umami. This Ring is an addition, no desert island stuff, but I'm glad it is there. Wilhelm Furtwängler may eventually have become affiliated with Richard Wagner, in name and fame, his favorite composer was Ludwig van Beethoven. The composer who, in 2020, thanks to that wretched bat from Wuhan, saw the festivities surrounding his 250th anniversary largely fall to dust. In the opening of the second part of his Seventh symphony (the Allegretto) Beethoven starts with an A minor chord. From there he goes to a combined E/G-major chord. Thus Beethoven says by musical means: "Happiness is there, where I am not". The Allegretto is melancholy in a majestic advancing chord progression. Resonation of the pace on which the mind seeks a place where relief and enlightenment can be found. At a time when we, even more than usual, have to depend on ourselves, the presence of good music, books and films is of more importance than ever. Extra thoughts and special thanks therefore to the writers and artists with which we (try to) make our way to the light at the end of the tunnel. The demands and expectations with which we burden their work may not always, especially now, be reasonable, but they stem from primarily felt needs: the need to enrich our inner self, to satisfy sincere curiosity and even to fight a deeply felt insecurity about our place in the world. It is all the more precious when music, books and films (art if you like) succeed in doing so and touches us where it enlightens the mind and gives us a glimpse of a world, deep within ourselves, that holds the promise and fulfillment to a better life.

- Wouter de Moor

1 Comment

And then you wake up in a world in which Eddie van Halen is no more. Like this year was not already strange and f*cked up enough. The fact that even musicians who, responsible for the soundtrack of your life, are bound to an appointment with the Grim Reaper, as if they were ordinary mortals, remains unabatedly disturbing. It plays one’s mind to no end, it makes one face the times beyond one’s own time, it makes one stop to function, not able to do the simplest of jobs. The death of a rock god lay bare that connection with music that is often more stronger, more intimate than the connections one has with spouses, friends and family. Because the music is always there. Unconditionally. It’s there for joy, sure, but it also keeps a mind in balance, it can be an invaluable partner that can get you through a difficult time. It triggers the imagination in unspeakable ways. Lost for words. Everything passes eventually but Music is so very present tense. And then being in a world where he is not in. Don't let the party antics of Van Halen's front men (Sam & Dave) fool you, Eddie van Halen's guitar tone was the heaviest thing in the known universe. (Play Romeo Delight and play the Annihilator cover from trash metal shredder Jeff Waters to prove a case in point). Pyro-technics, two-hand tapping and the trademark solos aside, the secret of EVH was in the rhythm, in the groove, in the heavy-metal-flamenco-style delivery of his licks. Never ‘just’ a barre chord or a mere repetition of riffs. Delivered with a right-hand attack, with his peculiar way to hold a pick, that burned strings and eardrums alike. (The quality of his rhythm work that, when Hagar became Van Halen's frontman and the songs more conventional, only got more prominent because Hagar "didn't want to sing over guitar solos". Bless Roth for songs like Hot For Teacher and As Is; riff clusters from which songs with lyrics are made. Chuck Berry on steroids. Pure gold because virtuosity is great but you carry it much better with you when you can sing along with it.) EVH was a musician that escaped the realm of the instrument he was playing (the notion that we lost the "Mozart of our times" is made more than once these days); he reimagined the electric guitar as a creator of sound. There is solace in good music, in inventive musicianship and EVH supplied that, in his own unique, idiosyncratic style, in large amounts. When I was young I wanted to be Him because for a child there is nothing more exiting than a big toy and in the hands of a rock god (how the hell is he doing that?), an electric guitar becomes the biggest toy of all - a magic wand with divine possibilities. Suffice to say that some dreams remain dreams. I often did not knew what I wanted in and from life but playing the air guitar? Always! Infinite pleasure in gesticulating, in dancing with your arms in thin air. Inexplicable freedom in expanding the mind with the idea that everything in life can be overcome, can be dealt with. Godly rewards from the fact that one can be, if only for the duration of a song or guitar solo, be bigger than life. We still have the music to revive dreams of old, as a gift for the ages, but His demise, like Neil Peart earlier this year, is hitting hard. Very hard. - Wouter de Moor

|

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed