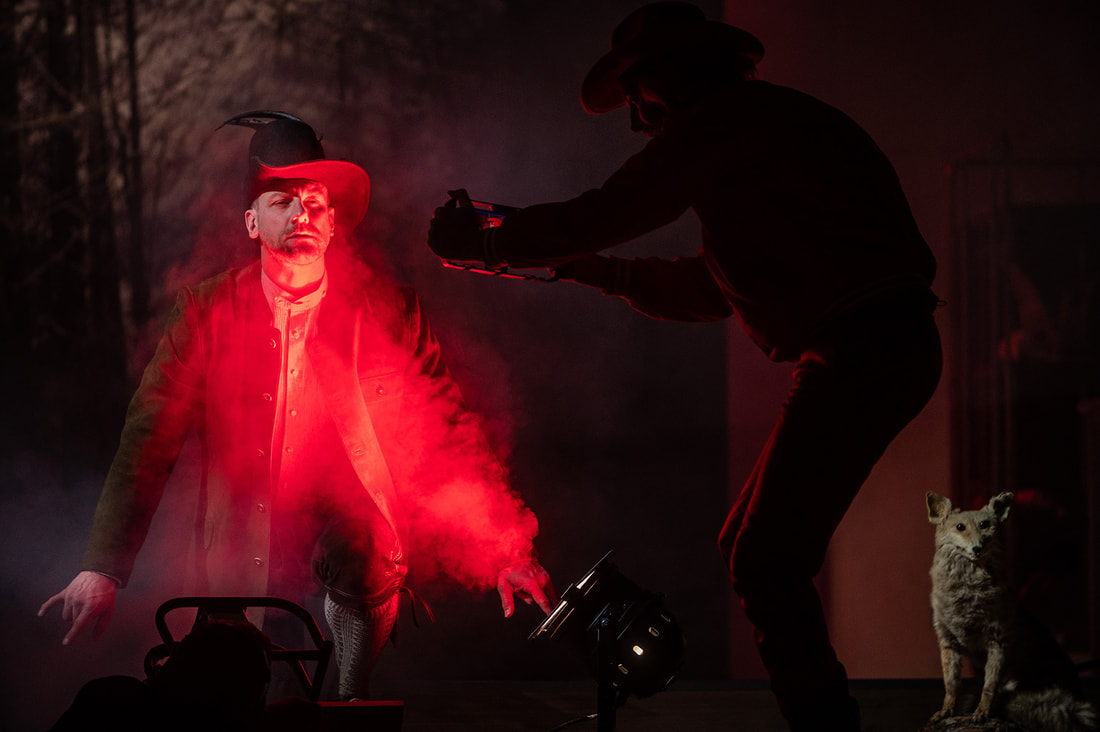

In his new production of Der Freischütz for the Dutch National Opera, Kirill Serebrennikov takes a rigorous approach, resulting in a surprisingly successful show that in all its exuberance celebrates the freedom of theatre and the beauty of music. One of the first complete productions that the Dutch National Opera put on stage again after the Covid lockdowns was UPLOAD, an opera by Michel van der Aa. It was a memorable production in every respect. Not in the least because the share of new operas in the programmes of opera houses worldwide can be called minimal to small. The world of opera relies on yesterday's repertoire, so how to keep that repertoire up to date and relevant for today's world remains a topical question. With this question in mind, Kirill Serebrennikov takes a rigorous approach in his new production of Der Freischütz for the Dutch National Opera. And comes up with an answer that can be called both surprising and successful. Rarely will an opera have been put on the cutting table as it has been here and seldom will the result, a kind of musical-theatrical monster of Frankenstein, have been so convincing. Carl Maria von Weber's Der Freischütz can be placed in music history somewhere between Mozart's Zauberflöte and Wagner's Fliegende Holländer. Mozart's opera as the source of inspiration for Weber, who in turn would inspire Wagner. Like Der Zauberflöte, Der Freischütz is a Singspiel in which arias are alternated with spoken dialogues that may not be called recitatives. (And because spoken dialogues were not allowed in the Paris Opera, Hector Berlioz arranged a French version of Der Freischütz in which the dialogues became recitatives and a ballet, entirely according to Paris Opera tradition, was inserted ). Those original dialogues by Friedrich Kind are not safe with Serebrennikov either. He finds them too old-fashioned and has them replaced with new English-language dialogues and monologues. This ensures, especially because the new texts keep up the momentum, that the music takes precedence. And that music is truly superb. It justifies that Der Freischütz should be performed more often. The score of Der Freischütz is lying on the piano, and R. says, "I just brought it out to show you who my master was," and he shows me the two orchestral bars preceding Agathe's "Wie nahte mir der Schlummer" aria the wide spread of the wind instruments - "He [Weber] was the first to write like that; it occurs in others in flashes, but with him it was deliberate." The more naturel ('realistic') you stage, the better you can see it is fake. Richard Wagner already realised this in 1876, at the premiere of his Ring des Nibelungen in Bayreuth. How do you avoid lapsing into stupidity when trying to find an answer to the question of which images to add to music and text? By taking some distance from the source material so that you let the audience do the work itself, by stimulating its imagination. By not taking the source material literally, but using it in abstract form as a grid for your performance. In what, for lack of a better word, could be labelled Regietheater, Kirill Serebrennikov presents a kind of meta-version of Der Freischütz. A production that recognises the problems that can occur in a more naturalistic staging, addresses them and then works around them. This is a production that is both a programme and a performance. We are made partakers of the inner struggles of the cast that has to perform the opera while we enjoy its beautiful music. Music that, apart from Weber, also comes from The Black Rider by Tom Waits (a piece of music theatre from 1990, with lyrics by William S. Burroughs, which tell the same story). In which Waits' music, played by a jazz combo on stage, complements (in all its contrast) surprisingly well with the orchestral splendour of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in the pit. In this production Serebrennikov introduces The Red One, a character that guides the audience through the story of Der Freischütz (played by actor Odin Biron who also plays in Serebrennikov's last film Tchaikovsky's Wife and sings the three songs by Tom Waits (Weber's accidental drinking of nitric acid, which reduced his voice to a grunt, is the bridge that is made with the songs of Tom 'grunt' Waits.) In the overture, we see the story unfold, accompanied by black-and-white video images - ideal for those new to this opera. In what follows, the scenes of the original story (the arias, the musical interludes and the choral pieces) will serve as a framework on which the singers/actors will hang their personal stories about their experiences in the world of opera. This Freischütz is a frame story in which the singers audition for a performance of Der Freischütz. Main character Max has to win a shooting competition in order to marry Agathe. The uncertainty about this is linked to singer Benjamin Bruns' "confession" about his wife wanting him to talk sexy in bed, in a deeper voice. Something he, as a tenor, feels deeply uncertain about. As Kaspar, Günther Groissböck plays an ambitious bass-baritone who wants to gain the conductor's favour in order to secure a solo role. In vain. At the end, he is sent back to the choir he came from. It mirrors the rejection of Agathe that befalls him in the original story. Agathe is sung by the South African soprano Johanni van Oostrum. The tension of her opera persona synchronises here with the stress of the soprano who is afraid for her career because younger colleagues (threaten to) outshine her. One of those younger colleagues is Ännchen, beautifully sung by soprano Ying Fang, who gradually becomes more estranged from her older colleague, the established soprano whom she considers a friend. Agathe and Ännchen are, as The Red One notes, actually two sides of the same coin; why did Weber not make one character out of them? It is one of the many comments The Red One makes in a production that almost apologises for the opera it puts on stage. Groissböck has a double role (well, a triple role, after all, everyone is already "himself" and the opera role he or she sings). After being sent back into the (hunter's) chorus, he enters the stage as a member of the audience, as the deux ex machina, Ein Emerit, from the libretto, to take care of the (far-fetched) happy ending of Weber's opera. A dynamic piece of music theatre in which we learn something about Der Freischütz and the opera-métier. Arias that serve to illustrate the themes embedded in the original story: fear of failure and the resulting uncertainty that makes one want to make a pact with the devil in order to achieve a goal. In this setup, the conductor is given the role of the devil's envoy, Samiel. He is the one who directs and must give his approval. As the devil's henchman, conductor Patrick Hahn rises impressively from the orchestra pit at the end of the Wolf's Glen scene. As the voice of evil, Hahn's performance is less convincing, his voice is too light (perhaps something could have been done here with a heavier voice from someone else, or even a voice modulator). Inspired by the optimistic years after the Napoleonic Wars, Weber and Kind attached a happy ending to Der Freischütz (where the original story of August Apel's Der Freischütz provides for a pitch-black ending, an ending that is maintained in The Black Rider, by the way). An optimism that is not directly in line with the present time. More than Kirill Serebrennikov might like, his Freischütz offers an escape from an ugly reality of war and displacement (at this point, Serebrennikov thinks there is a reasonable chance he will never return to Russia). A performance that, despite the mutilation of the original - it will no doubt divide opinion - does not close the door to that original and has something to tell to those familiar and those new to this opera. A Freischütz that, in all its exuberance and cheerful approach, celebrates the freedom of theatre and the splendour of music. - Wouter de Moor Der Freischütz (Dutch National Opera, Amsterdam, premiere 3 June 2022)

Libretto of Friedrich Kind with new (English) dialogues by Kirill Serebrennikov & Arseniy Fariatiev Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Choir of the Dutch National Opera Conductor: Patrick Hahn Director and stage: Kirill Serebrennikov Costumes: Kirill Serebrennikov & Tanya Dolmatovskaya Agathe: Johanni van Oostrum Ännchen: Ying Fang Kaspar + Ein Eremit: Günther Groissböck Max: Benjamin Bruns Samiel: Patrick Hahn The Red One: Odin Lund Biron

2 Comments

|

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed