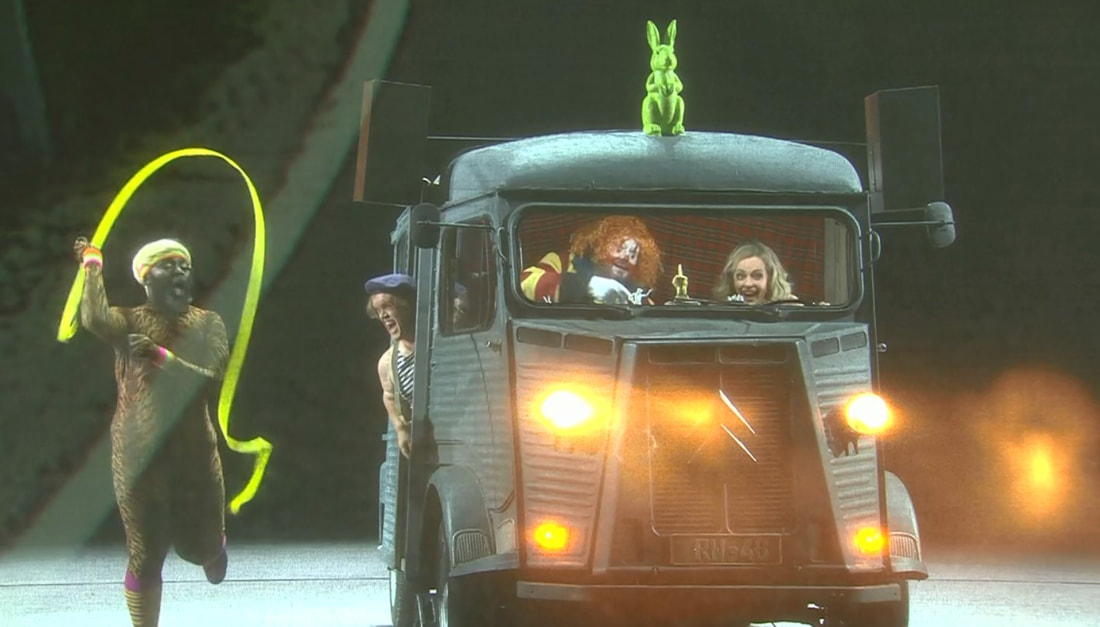

No Bayreuther Festspiele for me this year, at least not in the flesh. No descent into the Bayreuther mosh-pit but an ascent into cyberspace where, together with the rest of Wagnerians, I can rejoice at the virtues of the streaming services that make it possible to see the new production of Tannhäuser in real-time. Being part of a live audience is always something special, also when that audience is in cyberspace. Visiting Bayreuth is more than just visiting an opera. Bayreuth, for those with an interest in Wagner, is like an open air museum, whose magic works from the moment you step outside the station and you see, on your right, the road that leads to the Green Hill. In Bayreuth the whole city is a stage, with little Wagner statues to greet you and street names that remind you of the sole purpose of your visit. Here the combination of historical awareness and expectations, often sky-high after waiting for years to get oneself a ticket, create their own prelude to a performance that begins long before the Festspielhaus opens its doors. Five years ago I've visited the place for the first time. I went to see Lohengrin but more than that I went to see (and hear) the theater that the composer - who had become nothing short of an obsession by then - had built. Like a kid in a candy store, I had never felt so excited before a performance, not since I went to see the idols of my youth, Canadian rockband Rush, in concert many years prior. Lohengrin in Bayreuth was my acquaintance with the famous acoustics of the Festspielhaus and its infamous absence of climate control. Lohengrin in Bayreuth was also my first serious encounter with Regietheater (for lack of a better word). Hans Neuenfels' production made rats out of soldiers and gave, with animation and video, the original story a Rashomon-kind of spin. I did not comprehend it complety, by times the libretto seemed hidden behind theatrical extravaganza that was both entertaining and distracting. Needless to say I enjoyed it tremendously. Attending an opera in Bayreuth was a Gesamt-experience of many things: the notice that one was standing on - let's not get carried away but yeah - sacred ground, it was about music and one's own personal relationship with it, about theatre and the power of imagination and, of course, about the history of Europe and the sensitivites around Wagner that were nowhere better felt than in Germany. In Bayreuth, staging Wagner was a reckoning with the past. In the modern staging of Hans Neuenfels the avant-garde came from the need, had it roots in the conviction, that in order to keep Wagner's music dramas relevant for the present day they had to be saved from a stained past. So much I understood. It was not until a considerable time later that I began to appreciate Neuenfels' Lohengrin more for its artistic merits than for its good intentions. After Bayreuth I had bought a video of a Lohengrin with Placido Domingo in the title role. A traditional production by Wolfgang Weber with beautiful scenery. Cheryl Studer was Elsa and Claudio Abbado conducted, no complaints there. But after Act 1 I felt a bit bored and after Act 2 I thought: Why bother? Because for beautiful pictures to come with an opera I just have to close my eyes. You can make your ideal staging in the mind, Wagner's music supplies you with everything you need. After three acts of Weber's Lohengrin I craved for a staging in which the director had turned the scenery into something more than just a depiction of the obvious. A staging that was more than just an atmospheric picture to a story. I began to appreciate more the kind of staging that added its own dynamic to music and text, a staging that gave with theatrical findings, added plot twists and changed perspectives -even if those add-ons went against intuition and libretto-, the opera a more idiosyncrastic outlook; the kind of staging that not only served the storyline and libretto but also dared to operate on a more independent level. So I bought a DVD of Neuenfels' Lohengrin, the production I saw in Bayreuth, and was not disappointed. If I want to see a staged Lohengrin I return to the rats in the laboratorium rather than Domingo in a beautiful cloak acting like a statue. To the question what scenery to add to Wagner's music drama Tobias Kratzer already came up with highly praised answers for Götterdämmerung, a production that went - sadly - under my radar. In his Tannhäuser for Bayreuth he makes extensive use of video, grants the audience a view on the Wartburg, offers some more or less traditional stage imagery in the second act but hangs those bounded to tradition pretty much out to dry (and one is surprised, measured by the booing the production teams often receive, how many in the Bayreuther audience are still capable of being unpleasantly surprised, even shocked, by new ideas, so many years after Wieland Wagner dragged the operas of his grandfather away from romantic "naturalistic" scenery). In Kratzer's take on Tannhäuser the mountain of Venus becomes a circus company. It is here that Tannhäuser, dressed as a clown, lives the adage of the young Wagner („Frei im Wollen, frei im Thun, frei im Genießen“ / Free in the will, free in doing, free in enjoyment). In the circus of Venus, Tannhäuser finds the company of a drag queen (Le Gateau Chocolat) and a dwarf and together they drive around in a van. Tobias Kratzer likes to toy around with ideas and to tease, not only his public, but also fellow theater makers. In the overture we see the circus van pass a billboard with on it a reference to Joep van Lieshout's biogass installation of the previous Bayreuther Tannhäuser production („Biogas-Anlage mangels Nachfrage geschlossen“ / Biogas plant closed due to lack of demand). The circus van is going to the Burger King where they tap fuel from a parked car and leave without paying. When a police officer tries to block their way, Venus hits the gas and drives him over. From that moment Tannhäuser begins to feel remorse. There is a dark side to his freedom, the bohemien lifestyle comes with a price that he - by the time the overture is over - is no longer willing to pay. He goes back to where he came from. That place is Bayreuth. From the circus back to Bayreuth. From lowbrow entertainment to highbrow art. Tannhäuser is a story about love and lust and social acceptable behaviour. But here Tannhäuser is more about finding your place in society than trying to solve the problem of the masculin mind that tries to cope with both love and lust. Kratzer steps into the Bayreuther tradition of demythologizing Wagner and takes the themes of love, lust and salvation to micro-level. Makes them part of a story of human proportions in a production for a public that was raised with movies and video clips. Kratzer gives us Tannhäuser in the circus, and we connect it (amongst other things of course) with Fellini. The dwarf with a tin drum makes us think of Die Blechtrommel, a story about a kid that, in protest to the mature world, refuses to grow any further after his third birthday. And where a linden tree (ein Lindenbaum) to a 19th century audience, familiar with its literary meaning (a leitmotif for love and death), gave extra meaning to the song "Am Brunnen vor dem Tore" from Schubert's Winterreise, so the film references work for a 21st century audience as visual leitmotifs that emotionally widen the image of circus people as social outcasts. Bohemians whose drama often is hidden behind smiles. Love and lust are motives, raher than main themes, in a story of finding your place in the world. The sexuality is part of a lifestyle. It gives Tannhäuser flesh and blood and the result is moving. What if the place where you find love (and lust) is not accepted by mainstream society? How does one stay true to oneself when peer pressure forces you to change your ways? Kratzer leaves the religious aspect pretty much out of his concept (Rome is where the police station is) and transits Tannhäuser's story (and sexuality) to topical times with nods to the LGBT-movement. 20 years ago he sang in The Phantom of the Opera and now he has already 100 Tannhäusers under his belt (and he is on his way to 100 Tristans). Stephen Gould was a very impressive Tännhauser who had in Lise Davidsen a stupendous Elizabeth at his side. Last minute substitute Elena Zhidkova (she stepped in for Ekaterina Gubanova) carried the role of Venus on small but strong shoulders and brought comic relief to the role; in the second act she infiltrates in the singer context at the Wartburg where she can't barely hide her boredom about the prudery on display. As in both the Meistersingers from Katerina Wagner and Barry Kosky, and Stefan Herheim's Parsifal, we see in Tobias Kratzer's Tannhäuser Bayreuth on stage of the Bayreuther Festspielhaus. And like in Hans Castorf's Ring we find in the use of new media, video, means to extend the stage, to go where the eyes of the audience normally don't go, in this case backstage and outside the Festspielhaus. In a time with cameras everywhere, privacy is an illusion. We see Wolfram backstage, in distress, seemingly intented to call it quits, when someone with a score reminds him of his performance duties. The ambiguity of Wolfram, Tannhäusers friend who struggles more than anyone else with his love, lust and moral standards, gets a bit of a frightening touch here. He dresses himself in Tannhäuser's clown costume to get closer to Elizabeth. We’re eying to a Pagliacci turn of events when they kiss and we step into darkness when Elizabeth recognizes Wolfram but nevertheless has sex with him. By lack of the real Tannhäuser she settles for a substitute, she swops the real thing for an illussion. It leaves both Elizabeth and Wolfram devastated. Wolfram's aria: "O du mein holder Abendstern" becomes a cry of regret and Elizabeth eventually takes her own life. Elisabeth ends up dead in the arms of Tannhäuser while a video playing in the background shows us the two driving away in the circus van to an imaginary place beyond the horizon - the only place where their love can exist. It is a kind of a transfiguration in love, a fullfillment of the deepest of all desires far away from the material world, a salvation in mind only. From the circus back to Bayreuth to, eventually, a theater of the mind. Place where - as contemplated before - very often the finest of stagings are. Very often the finest stagings are in the head and sometimes all it takes is a head to make a fine staging. In this case the head of Nicole Kidman. From an opera staging with references to movies to a movie with a reference to opera. From Tannhäuser to Birth from Jonathan Glazer. In Jonathan Glazer’s Birth, Nicole Kidman is a woman who has lost her beloved husband. In shock and at a loss she marries a man she doesn’t really love. One day a boy shows up who claims to be the reincarnation of her dead husband. It brings her out of balance, it’s a thing that can, of course, not be true. Still unsettled by it, she enters a theater where a performance of Die Walküre is about to begin. During the overture we see her face, slowly descending from reason and common knowledge to a point where what is unthinkable, that her beloved husband came back to her, might perhaps be true. It is a movie within a movie, a scene that works on many levels; the new found function of the music, the role it gets apart from being an overture to an opera, the beginning of a night out – the promise of a new beginning in her troubled life. A scene like this, and I don't know of any other example where the use of Wagner's music outside his own operas works in such a transcendent way, is like a leporello that hides many questions and possibilities. For the Wagner afiencado, always glad to hear his music in unexpected places, the scene can harbour some questions about his or hers own relationship with the music of the sorcerer of Bayreuth. What does Wagner's magical world exactly add to one's own world? What is his music capable of doing? In the scene the music gives extra meaning to the slowly changing expression on the face of Nicole Kidman and that face, in return, adds another layer of meaning to the music. It is a scene where the relationship between fiction and reality, the friction between them, opens a door that reality and fiction alone can not open. It paves the way for the possibility that there is, in fact, something like magic. It can put Wagner's pretentions, art as a replacement for religion, into new perspective. It can be a reminder for what an opera staging can be, something that escapes the syntax of a nice picture that comes with beautiful music, something that perhaps can transgress genre and media boundaries, and brings the mind on a plateau from which opera and life look as new. - Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed