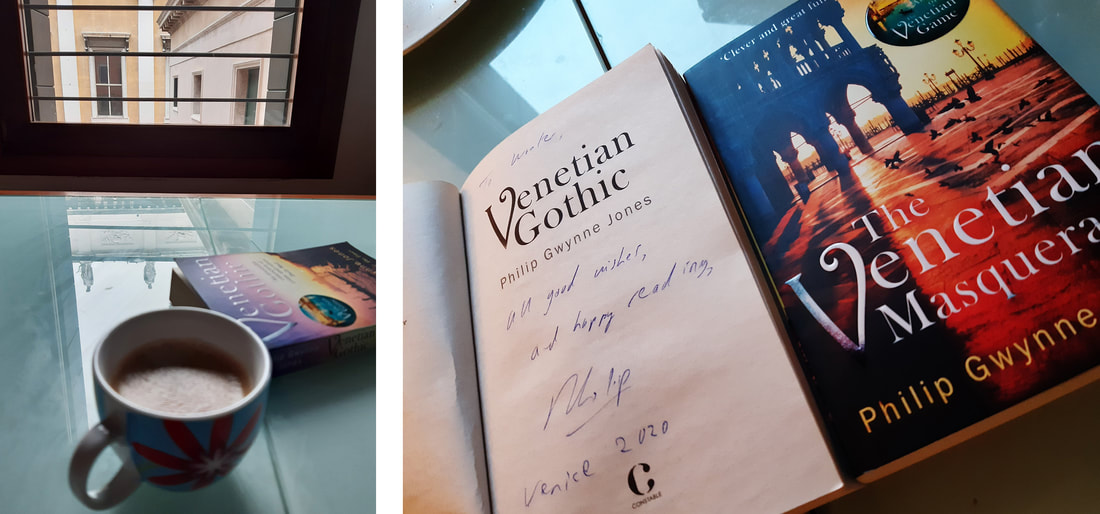

The winter is over. The Covid night not yet. The WAGNER & HEAVY METAL Spring Weblog steps into the light with a visit to Venice and meets up with a creature of the night. Reading time: 15 min A month after the premiere of Parsifal in 1882, Richard Wagner travels with his family to Venice to spend the winter there. In Venice, his health quickly deteriorates, he suffers a lot from spasms and he misses his books up there. But he does not think of going back, the idea of being locked up in the north (in Bayreuth) all winter makes him shudder. With the arrival of spring, the sun feels like a reminder of that inclination that can surface so strongly in winter. The inclination, that animalistic need, to escape the chilly gray of winter. Twenty-twenty, the year where everything came to a standstill, ended with a flight to Venice. A relocation to the city of the doges, magnet for artists, writers and composers. A relocation of the body to refresh the mind. The city, an open-air museum with its museums closed, with only a fraction of the number of tourists who normally roam there, became a setting for walks where Richard Wagner and Gustav von Aschenbach had left their real-life and fictional footsteps before they, for real and fictional, passed away there. The poetic potential of going to Venice at the time of a pandemic, city of the plague (quarantine) and cholera (Thomas Mann's Tod in Venedig), was not lost on us. Our stay became a sojourn in the city of gondolas and Acqua Alta (high water) where you felt the force of cultural heavyweights pulling at you without the need to draw that inexorable, ultimate conclusion. After more than a month we went home, without dying. Venice means a lot to a lot of people and the most extraordinary thing is that despite the seemingly endless influx of tourists who come here for the same thing, the city speaks to you in a highly individual way. That was what struck me most on my first visit two years ago. A visit to Venice has the immediacy of a live event where the massiveness of the audience does not get in the way of an intimate experience. A visit to Venice, instead of being an item on a bucket list that you tick off, was a place that you absolutely had to come back to. An introduction to a place that was more beautiful and fascinating than all the stories, photos and art could have prepared you for. As if behind the spugnatura texture of colorful walls and the amazing light (which Cosima writes about so admiringly in her diaries) there is a reflection and deepening of one's own emotional life. Beauty and decay are inextricably linked here, and nowhere more than here is it clear that decay, the ravages of time, the mortal aspect, is an inseparable part of what we experience as truly beautiful and valuable. Nowhere does decay look more beautiful than in Venice. Wagner had to do without (most of) his books in Venice. Nowadays, we simply take a library, more books than we can read in a lifetime, with us on an e-Reader. Indispensable for those traveling but in Venice, being with the books of Philip Gwynne Jones (and the author himself, a Spritz Venezia with Campari and no Aperol because that's too sweet) was a welcome reminder of the unsurpassed excellence of the paper book. Philip Gwynne Jones' paperbacks with relief covers (as good paperbacks ought to have) were a very fine tactile addition to the digital reading routine. Jones has lived in Venice for a decade, and his books bring together crime and culture. His stories are like tourist guides to the most beautiful city in the world in which a crime is committed. Stories that revolve around Nathan Sutherland, English Honorary Consul to Venice, and his girlfriend Federica. A man who spices up his conversations with his spirited girlfriend with nerdy details about music and film. It makes the adventures they have together all the more empathetic. It scores Nathan Sutherland, the man who, to his regret, does not share his birthday with Tony Iommi by only one day (-1), sees that somewhat made up for by the fact that he does share his birthday with that of Yoko Ono (+2), some bonus points on the list of nerdy coincidendes from yours truly, who shares his birthday with that of John Lennon (+10). "Are you sure Philip Gwynne Jones doesn't know you from way back?" my girlfriend asks me as she takes note of the passage below from "Venetian Gothic" after I break the living room silence with a hearty burst of laughter. Fede rested her head on my chest, and looked up at me. She raised her eyebrows, but didn't say a word. ‘Hawkwind,’ I said. ‘Oh’ “Assault and Battery". It's from Warrior on the Edge of Time. ‘Oh.’ She closed her eyes. ‘Were you single for a long time, Nathan?’ (Venetian Gothic, Philip Gwynne Jones) The scene above, together with the author's fondness for hardrock, opera and classic horror movies, might indeed suggest something like that. The scene is recognizable to the point of being uncomfortable. Books and stories can be like rabbit holes you disappear in when you hit the bookshelves or search on YouTube for that one novel or movie referred to. The same here. The happiness of scenes that remind one of what a person has read and experienced is amply provided for in the stories surrounding Nathan Sutherland (who couples his incisiveness in thinking with an acting in anti-James Bond style, when punches are dealt he is usually on the receiving end). The stories are a pleasant adventure novel-like extrapolation of the Venice you have come to know as a beautiful city where actually no murders are committed on a regular basis and are, in addition to being highly entertaining and very educational, a pleasant wander - far away from the all-consuming ordinariness that everyday life can be so burdened with. ‘Welcome to my home,’ she said. ‘And leave something of the happiness you bring,’ I whispered to Federica. ‘What's that?’ she asked. ‘It's from Dracula.’ (The Venetian Masquerade, Philip Gwynne Jones) Ever since I read the book (at the age of 13 during a holiday in France, on a camping near an old castle) it has been among my favorites. A book in which the evil depicted is so chilling because it remains, for a large part, hidden from view. It is perhaps for this reason that no film (entertaining though they are) has ever been able to do full justice to the story that Bram Stoker constructed in his epistolary novel around the chief of all vampires: Dracula. The conversion of the epistolary novel into an anecdotal narrative in which the many narrative perspectives are exchanged for the single perspective of an omniscient camera does not do justice to the fantasy to which the book so successfully appeals. In the book, Dracula finds himself on the convergence lines of several points of view. He becomes visible in the traces he leaves behind, described in letter fragments and newspaper clippings. The link between the horror and the man, the creature, we have come to know at the beginning (through Jonathan Harker's diary entries) becomes clear only later. A new Nosferatu by Robbert Eggers is planned (which draws on Murnau's 1922 film) but perhaps director Karyn Kusama (Jennifer's Body and The Invitation) will find the key to the ultimate Dracula film. She has a Dracula film adaptation in the pipeline that, being the first, takes the premise of the different narrative perspectives from the book as its starting point. In writing Dracula, Stoker was actually aware of the theatrical potential of his master vampire. Stoker was a man of the theater himself and managed the Lyceum Theater in London, headed by Henry Irving, an actor whose intense portrayings of diabolical roles (amongst them The Flying Dutchman) were a source of inspiration for Dracula. Since then the chief vampire made his appareance in a wide variety of stageplays, movies, musicals, an opera (by The Royal Swedish Opera) and a ballet. Guy Maddin, Canadian cult director (The Forbidden Room was one of the best cinematic experiences of recent years), ventured in 2002 with a film adaptation of a ballet of the Dracula story (Royal Winnipeg Ballet's interpretation of Bram Stoker's book) and came a long way when he fused silent-film techniques, avant-garde imagery and music by Gustav Mahler into a 21st century theater of Gothic Grand Guignol. The vampire in Dracula: Pages from a Virgin's Diary is of Asian origin, and in that guise he carries with him not only the cross of the vampire but also the cross of the foreigner. In this Dracula adaptation, the deeply human characteristics in a being from another, inhuman dimension, are embedded in a current social and societal framework. This widens the image depicted of the chief vampire; he is more than just evil. Guy Maddin provides his Dracula with atmospheric images (he has that in common with other Dracula films) and relies on the power of suggestion with the abstraction of a ballet choreography. It doesn't get as good as the book (obviously) but the imagination of the book finds a worthy counterpart in Maddin's imaginings. The vampire condemned to wander eternally in the underworld shares his fate with that of the Flying Dutchman. Trapped by a curse that forever bounds them to the earth, they withdraw from the world of the living and the rules that govern it, in order to seek relief and salvation from someone, preferably a woman, who makes herself available (voluntarily or by force) for the purpose of supreme liberation. In this (very Wagnerian) premise, the woman, in the brisk combination of being both commodity and savior for the man, may indeed rejoice in her indispensability, her personal ambitions will not have to extend beyond being subservient to the man (synonymous with how Cosima put her life at the service of Richard Wagner and his genius, and saw that as her highest possible goal in life). In all my sad thoughts about life I am always uplifted by the knowledge that it was permitted to me to become necessary to him. Cosima's diaries - 22 Nov 1870) Where Richard Wagner's influence in music was considerable, his influence outside of music was possibly even greater. There was not an artist at the end of the nineteenth century, beginning of the twentieth, who did not emerge from under his shadow; his presence was ubiquitous. No wonder that Wagner's ideas about theater, music and drama ushered in the then new medium of film at the beginning of the twentieth century. The Dracula film that would be at the foundation of a genre not excluded. #1 Scene from "Dracula" (Tod Browning 1931) In what may have yielded the best-known Dracula to date, the 1931 Tod Browning film in which Bela Lugosi shaped the Transylvanian vampire with an affectionate accent, we hear the overture from Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg as Dracula visits the opera (see clip #1). Simultaneously with the version for the English-speaking market, a Spanish-language version was shot (directed by George Melford). In that Spanish-language version the character of Dracula is a lot less successful in becoming a movie icon but the editing of the film is superior to its English-language counterpart. Also in the Spanish version, Dracula goes to the opera but more than in the Tod Browning film, the music of overture Meistersinger is here not just a reminder that we are at the opera, a musical fragment as a leitmotif, but a serious host for the dialogue that takes place over it. (Apparently, the overture of an opera is the appropriate time to engage in extensive conversation.) #2 Scene from "Dracula", the Spanish-language version (George Melford 1931) Both Meistersinger and Dracula present us with the woman as an object of desire and as being a savior. And in both Dracula and Meistersinger, it is the father who exposes his daughter to evil and/or danger by respectively introducing her to Dracula (see clip #2) and awarding her to the winner of a singing contest. In Dracula, it is Mina who is 'privileged' to enjoy the special interest of the title character. In Meistersinger it is Eva who revels in the interest of several men of whom the interest of Beckmesser leaves the most unpleasant aftertaste. He is not seen (only) as a Jewish caricature anymore (a character of lesser morals) but in Beckmesser's interest in Eva, versus Walter's feelings for Eva, low intentions against those of true, pure love become visible. In the Spanish-language version, as if in coupling with Meistersinger, "Mina" is called "Eva”. It is as if, with the music of, and reference to, Die Meistersinger, the filmmakers want to tell us something about the similarities between the story and the characters in Dracula and in Meistersinger. Perhaps the filmmakers want to point out to us, the audience with knowledge of opera, the similarities in the fates these two women share in both film and opera. Coincidence or not, we Wagnerians who always like to see the grasping claws of the master reach as far as possible outside the realm of his own operas will of course gladly accept the invitation to draw conclusions about this commonality. Both Meistersinger and Dracula present us with the woman as an object of desire and as being a savior. With what Dracula can tell us about Meistersinger, we let our light shine on the motives of two male characters in the opera. It is difficult to perceive in Beckmesser, the master singer who manifests himself as a charlatan, noble motives for his actions and his desires. He is, at first glance, best suited to the role of the proverbial leech, the man who parasitizes on the skill of other people. If Beckmesser is Dracula then Hans Sachs is the most appropriate person to be Van Helsing. in Bram Stoker's book, Van Helsing is a man who carries along his own mania. He is aware of the contradiction that only superstition and delusion can point the way back to the normal world. As a fighter of creatures that belong only in legends, he engages in his own kind of Wahn, Wahn, überall Wahn. But to confine ourselves to the Beckmesser-Sachs tandem as a vampire and its hunter would ignore the fact that the character of the vampire, in all its multicolored greyness, has gained in substance throughout time. Why not give it a twist?

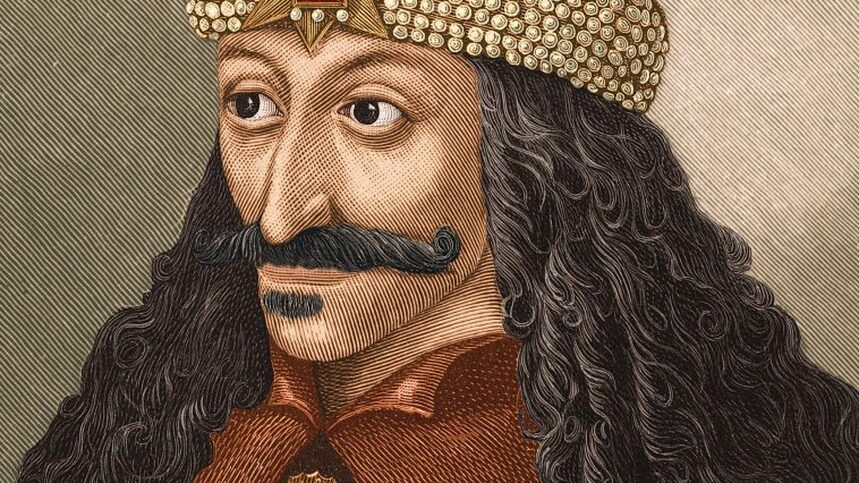

What if Hans Sachs, once night has fallen, leaves his home to indulge in innocent virgins? Abusing his position as a distinguished citizen in order to do the very thing he seems to have renounced for the eyes of the outside world. Well, in a world where Pride & Prejudice and Zombies exist, there surely is room for Meistersinger und Vampire. There is another, not fictional, but historical link that connects Dracula with a Meistersinger in Nürnberg. Before the real Hans Sachs, master singer and shoemaker, was even born, a poet named Michael Beheim lived and worked in Nürnberg. He was a (proto-)master singer who lived from 1416 to 1472. Beheim was Germany's most prolific poet of the 15th century. At the courts he was a frequent and welcome guest. In 1472 he was murdered under undisclosed circumstances. Beheim lived in a time of Papist emperors, Protestant secessions, Turkish invasions, and pagan rulers in the east. One of those rulers was Vlad Tepes, one of the inspirations for Stoker's Dracula. In 1463, Michael Beheim wrote a poem (Gedicht über den Woiwoden Wlad II. Drakul), a master song, or at least a prototype of a master song about Dracul, Vlad Tepes III, a sadistic ruler who took pleasure in impaling his enemies, women and children not excepted. In order to properly enjoy the macabre scenes that resulted, Vlad occasionally enjoyed a meal next to his impaled victims. Mainly because of a sloppy translation of the poem it was that Beheim's poem about Tepes and his barbaric savagery gave the suggestion that Vlad, like his fictional afterbirth at the end of the 19th century, drank the blood of his enemies (giving Stoker the inspiration for a bloodsucking Dracula) but that is most likely nonsense (Stoker most probably wasn't even aware of Beheim's poem when writing Dracula). Not that there wouldn't be plenty of horror left without that proto-vampire bloodsucking. Washing your hands in the blood of impaled people while having dinner scores high enough on the ladder of psychotic behavior to make it into a legend. Beheim based his poem in part on the testimony of a Franciscan monk, Brother Jacob, who had survived Vlad's atrocities. The horror of which the poem reports was an illustration of the cruelty of the godless Vlad, who, in contrast to the true faith of the Catholic rulers of the day, added an exalted lustre to noble Christian morals. From: Gedicht über den Woiwoden Wlad II. Drakul (Michael Beheim)

The historical Dracula saw himself, in his lifetime, materialized in literature by a poet in Nürnberg. A minstrel, who lived in the generation before Hans Sachs. Centuries later, the music of the Meistersinger von Nürnberg, an opera that takes the historical Hans Sachs as its inspiration, would accompany Dracula as he makes his way to the opera in a movie that bears his name. May we ourselves be able to go to the cinema and theater again soon, at a time in the not too distant future. So that we can once again experience the immediacy and excitement of a live performance in a world in which we do not have to rely solely on the pixilated reality of streams on a screen (no matter how welcome they are). - Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

|

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed