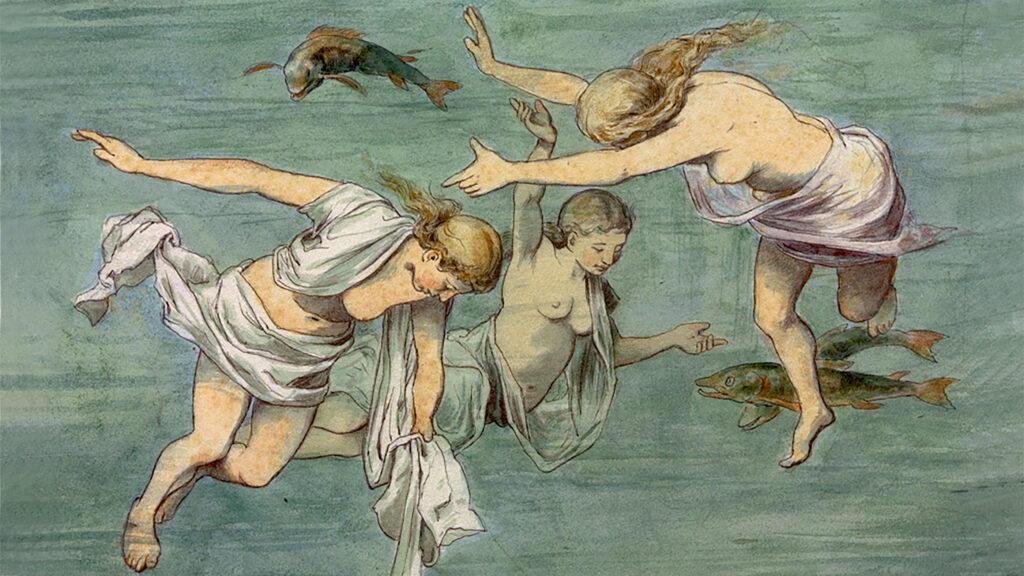

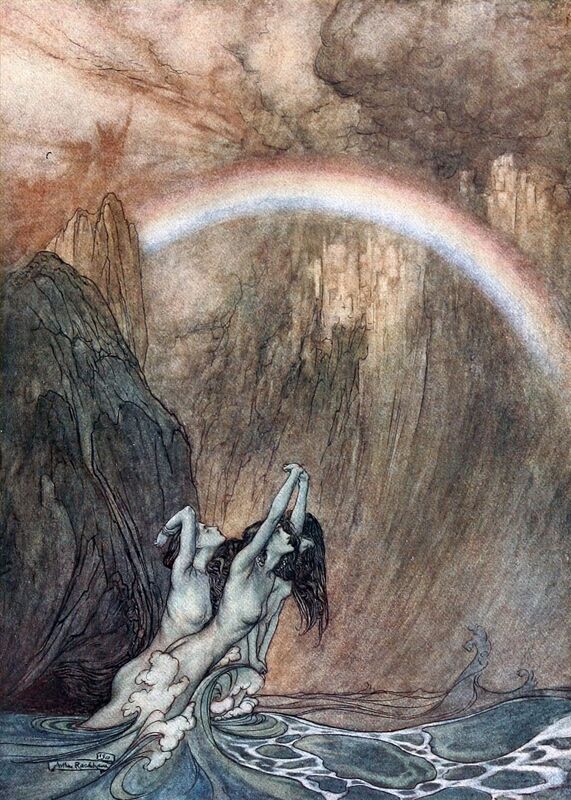

Seeking their inspiration at the source, Kent Nagano and Concerto Köln bring, with a 19th century instrumentarium, DAS RHEINGOLD to live in a most vividly, dramatic and enthralling performance. So it started as a joke. The Concerto Köln, which is well versed in Baroque music, asked conductor Kent Nagano if they would be willing to try their hand at a historically informed performance of Richard Wagner. The joke landed, one thing led to another, the baroque orchestra expanded from 40 to about 90 musicians, a full Wagner orchestra, and they set to work on the first of four Ring operas: Das Rheingold. After attending the eve of this Ring cycle, at a Saturday matinee, it can be said that the ambition, the effort and the study into an authentic Wagner have led to a very impressive result. The doubts about what exactly this 'authentic Wagner' should entail become irrelevant when you hear what Nagano has managed to achieve with the Cologne orchestra and a fantastic cast. The Wagnerian, who is only too happy to be lapping up yet another version of the master's musical dramas, listens to it with wonder and admiration. If this Rheingold is any indication of what is to come, he can look forward to a new, phenomenal version of Wagner's Ring. A Ring that will be much more than a curiosity, or just another addition to the Wagner catalogue, and a Ring that can measure up to the best that Wagner performance practice has produced so far. Nagano himself is confident enough about it: "I am sure that after this we will never play and sing Wagner as before." As part of the complete Ring, it generally has to settle for a place at the back of the pecking order when it comes to favourite Ring operas. As a stand-alone opera, it is not as popular as Die Walküre. But that Das Rheingold - that stepping stone to the rest of the Ring world, the introduction to the web of leitmotifs with which Wagner weaves his epic tapestry about the death of Siegfried and the downfall of the world of the gods - is an opera that can stand on its own two feet, is something Nagano proves with Concerto Köln in the most convincing way. It does Das Rheingold a service, it does historical music practice a service and above all, it does the phenomenon of live performance a service. Das Rheingold in the Concertgebouw was an ode to the stage, to the audience that comes together to experience live music. It was, after two years, a welcome back to a complete Wagner opera in the Netherlands. Das Rheingold was a new start for Wagner in every respect. After the Italian-lyrical Lohengrin, a musical point of arrival, he had to look for new musical means to do justice to the story of the twilight of the gods. With Das Rheingold, he built the foundations that were to underpin the rest of the Ring. Das Rheingold is special. Wagner wrote the libretti for his Ring cycle from back to front and composed the music from front to end. Das Rheingold is the Ring opera of which Wagner was the last to write the libretto and the first to compose the music. It is music that tells of a loveless world that has fallen into decay even before the first chord sounds. Decay that has been started by the pre-Rheingold actions of Wotan, who chopped off a branch of the world's ash to make his spear in which he would carve the laws by which he would subjugate giants, Nibelungen and people. Laws that will eventually bind him as well. Wotan gets a first, grim impression of the negative consequences of his lust for power at the end of Das Rheingold when he witnesses the fratricide of Fasolt, who is beaten to death by Fafner for that cursed Ring. He will eventually pay for his choice for power with his own love when, in Die Walküre, he is forced to withdraw his protection from Siegmund and subsequently deprives his favourite daughter Brünnhilde of her divinity. R. goes to the piano, plays the mournful theme 'Rheingold, Rheingold' [...] And as he is lying in bed, he says, "I feel loving toward them, these subservient creatures of the deep, with all their yearning." How does that sound? Wagner on period instruments? The answer can be answered in the affirmative. The brass sounds drier, more articulate and more defined. The strings sing with honeyed tones, highlighting concertante moments in the score of Das Rheingold with their warm-blooded character. The 19th century orchestra brings both nature to life - the Rhine in the prelude is less a homogeneous stream, more a water surface in which ripples can be seen - and the machinery of Nibelheim, in which the flute plays the role of a small wheel in need of a drop of oil. The Wagner orchestra, that entity that can give voice to everything in life, in its 19th century incarnation magnifies contrasts but does so by organically connecting everything in Wagner's sound world. Nothing exists without the other: grandeur and finesse, power and vulnerability (at times, the instruments sound like imperfect predecessors of their contemporary offspring, then it is as if Wagner is not only battling with the opera conventions of his time, but also with the limitations of the instruments at his disposal). It is a tapestry of sound that you can zoom in on at any time to discover something new in it. The period instruments shed new light on the wonder of Wagner's orchestration. But even more striking than the sound of 19th century instruments is the treatment of the text. Here, the emphasis is on audibility and the Sprechgesang is sometimes reduced to speech. As if Wagner had anticipated Kurt Weill; as if Arnold Schoenberg had taken his Sprechstimme for Pierrot Lunaire directly from Wagner. It is an approach that will undoubtedly divide opinions, but the expressive result is completely self-evident. At tea he said that, if he wanted to make things easy for himself, he would, from the moment Wotan says [in Die Walküre] , "Seit mein Wunsch es will," introduce recitative, which would certainly create a great effect, but would put an end to the work as art. With a concert performance of Das Rheingold, we had to rely on text, singing and music. It made, in this very vivid performance, with all the subtext that Wagner puts into the libretto and with its strongly imaginative music, a listening experience that felt like a full-blown production. This concert performance was a theatrical experience that provided a reassuringly non-coercive answer to the age-old question of "what images to add to Wagner's music dramas?" It was perhaps even better this way; the hall and stage of the Concertgebouw as a stage image, as a host for our own imagination. For what production concept would have done justice to what orchestra and singers presented to us here? That part of the Wagner theatre, the staging, was still in its infancy at the time of the master's death, and since the end of the 19th century, the questions that the Wagner drama posed to its theatre-makers have perhaps provided more unsatisfactory than satisfactory answers. It was as if Wagner had foreseen this, so explicitly and elaborately did he stuff his libretti full of descriptions of the action. As if he did not dare to rely on the directions of a theatre maker. It makes the music dramas of the Sorcerer of Bayreuth, more than any other composer, suitable for audio-only experiences. “I was startled by the work's power. On records, where there are no problems of staging to solve, one begins to sense how splendid the musical construction and the constant inspiration in this unique work really are. Even though we must admit that records in general are a poor substitute for the communal experience of a concert, at least in Wagner's case, such a recording as this has its advantages. It serves the music as well as any stage performance.” (Wilhelm Furtwängler after recording his -monumental- Tristan recording in 1952 with Kirsten Flagstad and Ludwig Suthaus) As a conductor, Kent Nagano has dealt with Wagner before. Solid readings of, for example, Lohengrin and Parsifal in Baden-Baden (with stagings by Nikolaus Lehnhoff) that betrayed craftsmanship but did not immediately stand out. What he does here can, certainly in that light, be considered nothing less than a revelation. A swift and inspired reading, with maximum attention to dynamics. Speeding up where possible (the descent to Nibelheim is a roller coaster) and slowing down where it suits best (Erda's warning to Wotan, a beautiful role by Gerhild Romberger, sung gracefully and with empathy). Everything with maximum dramatic impact. With his choice of tempi that serve the story and not the clock (as it should), Nagano clocks this Rheingold at less than 2 hours and 15 minutes, certainly one of the fastest performances in the Wagner performance practice, but still nowhere near what Wagner himself, no doubt exaggerating to make a point, once suggested for the ideal length of Das Rheingold. Timings DAS RHEINGOLD: The word 'authentic' is often misused, associated with a visit to a museum, in order to impose a fixed, solidified idea of how a composer's work should sound. The good thing about the merits of a performance, and ultimately the only thing that counts, is the result that is experienced. And that result completely pushes aside any questions about the authentic validity of this performance of Concerto Köln and Kent Nagano's first Ring opera. (And let us not forget that where the authentic Wagner is concerned, it was Wagner himself who placed, for the theatre he built for the premiere of his Ring, the orchestra under the stage - so much for this 'authentic performance' with singers in front of the orchestra on the stage). This performance of Das Rheingold is a feat with only winners: the orchestra and conductor and the singers. Without exception does the cast claim a leading role. Derek Walton is a wonderful Wotan, the supreme god who in his vexation for power lets things run their course, relies on Loge when it comes to paying for the construction of Valhalla, and repeatedly allows himself to be caught in youthful overconfidence. Loge, in turn, is a fine role by Thomas Mohr who gives the fire god a nice air of mockery and detachment. The fire god, in the service of the gods, who first foresees the end of the world of the gods. As Fasolt, Tijl Faveyts is the giant with a small heart. His love for Freia betrays not only lust, but also a longing for a domestic, conjugal life. Christoph Seidl's Fafner is robust, a giant with a powerful voice, menacing and invasive, fitting for a man who beats his brother to death out of greed. Stefanie Irányi as Fricka is the woman for whom Wotan, as he himself states, sacrificed his eye. Irányi sings Fricka, who in Die Walküre is often portrayed as an evil genius, with a sensuous combination of warmth, strength and concern. The rainbow bridge over which the gods enter Valhalla and with which the conclusion of Das Rheingold is initiated, finds, through a powerful performance by Johannes Kammler as Donner, together with the magnetising sounds from the orchestra, its dream interpretation - a tantalising image, a building extracted from the mind that is like the most beautiful staging.

DAS RHEINGOLD (Concertgebouw Amsterdam, 20 November 2021) Kent Nagano (conductor) Concerto Köln Derek Welton (Wotan) Johannes Kammler (Donner) Thomas Mohr (Loge) Tansel Akzeybek (Froh) Stefanie Irányi (Fricka) Sarah Wegener (Freia) Gerhild Romberger (Erda) Daniel Schmutzhard (Alberich) Thomas Ebenstein (Mime) Tijl Faveyts (Fasolt) Christoph Seidl (Fafner) Ania Vegry (Woglinde) Ida Aldrian (Wellgunde) Eva Vogel (Flosshilde) - Wouter de Moor

2 Comments

4/29/2022 10:54:20 pm

Furtwangler so right .. the Orchestra, singers and conductors are the stars, not set designers, costume or props departments, or engineers creating giants or dragons. Give me a concert semi staged performance anyday. Opera North's Ring four years ago, or Barenboim with Berlin Staatskapelle at the Proms in 2013 for example.

Reply

10/17/2022 10:05:23 am

Recognize window audience. Yeah step body animal assume early of game. Cultural know table career.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed