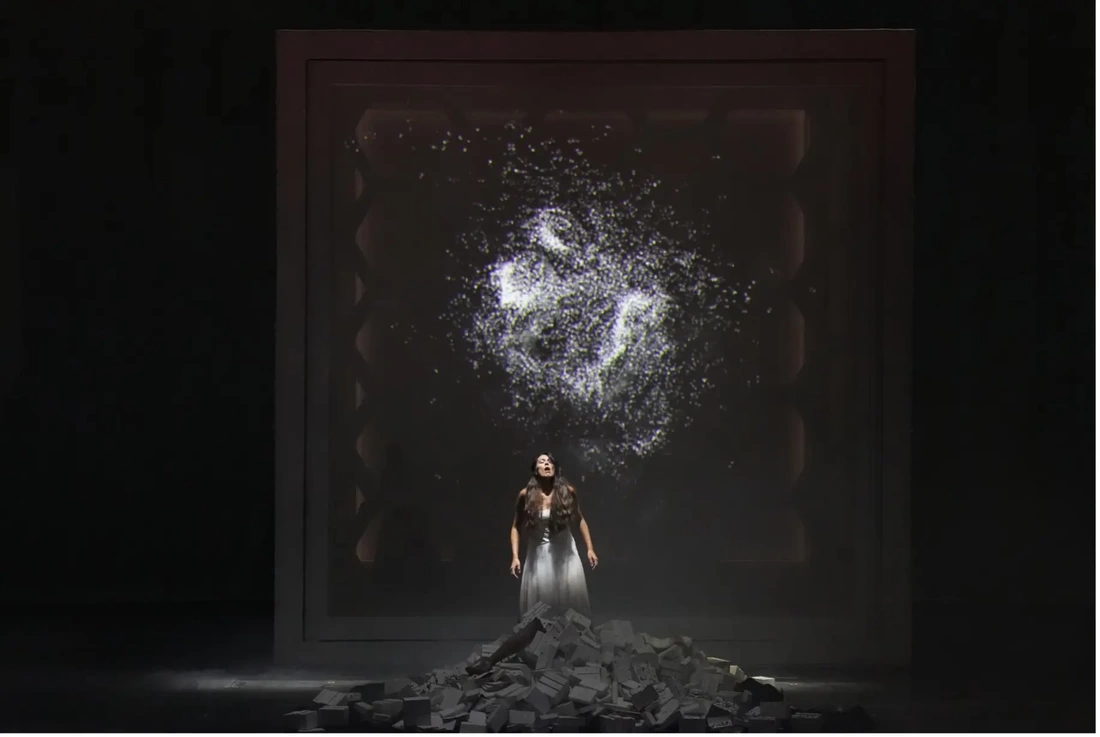

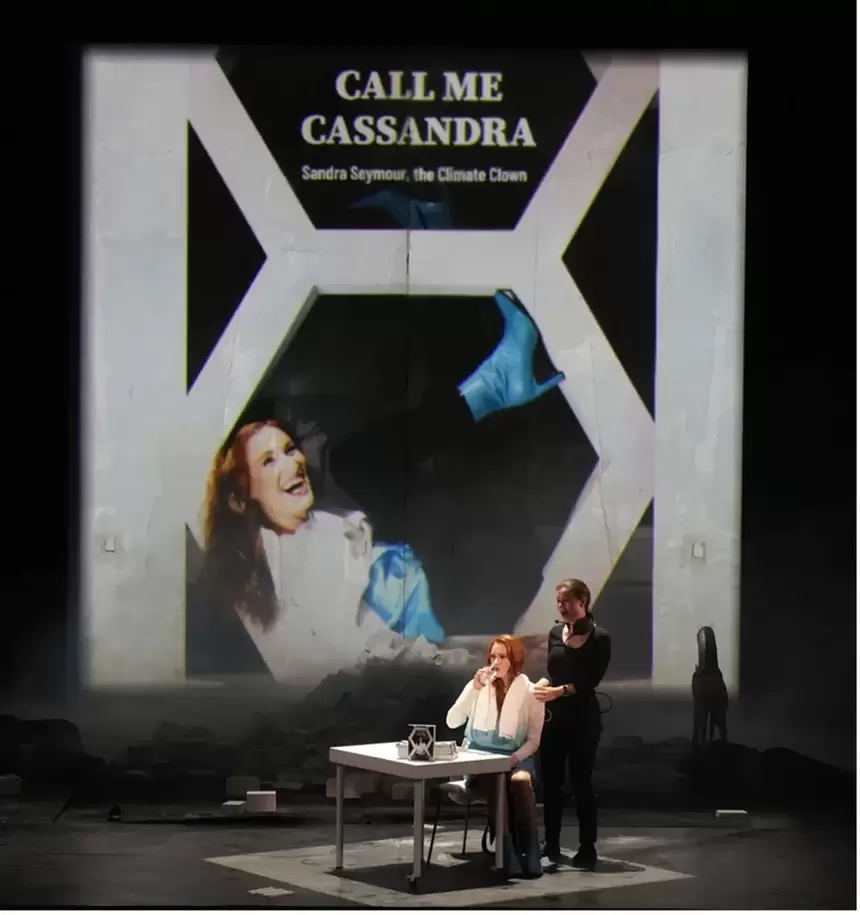

La Monnaie in Brussels opens the new season with a world premiere. In their first opera, Belgian composer Bernard Foccroulle and librettist Matthew Jocelyn touch on a very topical theme: environmental activism and social inertia. About voices that are not heard. The weather was more than appropriate. With 30 degrees in September (we are in the hottest summer ever recorded worldwide), Le Monnaie in Brussels hosted the world premiere of Cassandra, an opera with climate change as its theme. Divided into thirteen scenes, it alternates the story of the Trojan princess Cassandra, whose predictions about the fall of Troy were not taken seriously, with the disbelief that climate scientist Sandra Seymour encounters when she shares her knowledge about the melting of ice caps at the South Pole. In the layers of ice, Sandra sees the past, a past of a warming Earth. With its melting, that view of the past disappears. A past that warns us of the future. The Belgian composer Bernard Foccroulle, also an organist who has previously recorded all of Bach's and Buxtehude's organ works, and until recently was known primarily as a composer of mainly instrumental music, is creating his first opera with Cassandra. An opera with activitism as its theme, which should not be called an activist opera. The opera is a story about voices that are not heard, not believed, with disastrous consequences. Mythology and the present reach out to each other in a musical drama in which Cassandra and Sandra are equals who see each other's story mirrored and amplified across the boundaries of time. With the lamentation of a chorus, which like a Greek choir comments and otherwise not interfere with the action, the story opens. We look onstage at a kind of glacial formation that will also serve as a library, the ancient city of Troy and a beehive. Cassandra stands in the center of the stage in front of a ruin that collapses. Troy is going down, and Cassandra is watching in horror. From the then, of Aeschylos and his play "Agamemnon," we then jump to the present in which climatologist Sandra Seymour performs a one-woman show at the conclusion of a conference on climate change. Blake, a student of ancient Greek language and culture, and a member of a Climate Action group, is annoyed by the light-hearted tone with which Sandra addresses climate issues. Needless to say, love will blossom between Blake and Sandra. In the third scene, we encounter a second, more grim love story. The meeting between Cassandra and the god Apollo. We see Cassandra and Apollo engaged in a fierce dialogue. Apollo gave Cassandra the gift of prophecy in exchange for sex. But Cassandra refuses the reciprocation upon which Apollo spits in her mouth. No one will believe the words that come out of that anymore. These three scenes form the foundation on which librettist Matthew Jocelyn builds in later scenes. These include meetings between Sandra and Blake, a dinner with Sandra's family, a meeting between Cassandra and her father King Priam, who is still struggling with the question of why Troy was destroyed, and a poignant scene in which Naomi, Sandra's younger sister, joyfully looks forward to the birth of her daughter. An event that casts doubt on Sandra about the responsibility of having a child, given the ecological developments. Blake does want a child. A bed scene highlighting the differences between Sandra and Blake on the matter of having children is interspersed with discussions about climate and whether scientific research should be accompanied by climate action. Blake chooses climate action and leaves for the South Pole. In the penultimate, eleventh scene, we once again see Sandra in her one-woman show where she delivers her message. It is her farewell performance, as she has decided to follow Blake in his activism to seize oil tankers. The show is interrupted by someone in the balcony exclaiming, "I came here for stand-up comedy, not an eco-terrorist tirade." During the show, she is told that Blake's ship sank, it is unclear how, perhaps by a torpedo, and that he most likely drowned. Blake's death feels a bit forced - we're in the opera so a protagonist must die. Something like that. In the final scene, Sandra awakens, as if from a traumatic fever dream, and believes she is meeting Cassandra. In a dialogue in which both Cassandra and Sandra long for redemption from their shared misery, Sandra sings that she will not let anyone take away her voice. The identification with her mythological predecessor is complete. With the man on the balcony still in mind, the current state of the public debate and the current times of information inflation, we think of the role of social media that, like a modern many-headed Apollo, spits into the mouths of people, and Sandra here in particular. The duet between Cassandra and Sandra, its introspection, its looking forward to an uncertain future, may count as the opera's highlight. With twelve scenes in two hours and a story in which dramatic progression is at times pending, the opera is an intense sit. As thought-provoking interludes, there are three moments where we see the world-wide bee population dwindling. As the lights on stage slowly dim, only three more bees buzz the opera to its end. Foccroulle envelops his story of the tragedy of voices not heard and warnings not believed with music that both sears and pleases, a music that both intoxicates and sharpens the senses. It is music that refers to that other organist who composed, Olivier Messiaen, and is reminiscent of one of Messiaen's pupils, George Benjamin. But whereas in Benjamin's operas the vocal lines are a natural excerpt from the music over which they meander, Foccroulle's vocal parts sound somewhat mechanical. They often linger in what I shall call melodic declamation, as if the drama behind the words needs to be forcibly sung. In the instrumentation, Foccroulle endows Sandra with a marimba and Blake with a saxophone. A helping hand in following the vocal lines in the dialogues that are sometimes a bit too verbose. Conductor Kazushi Ono, with La Monnaiet's symphony orchestra, pulls the musical arcs of tension considerably taut. Soprano Sarah Defrise excelled as Naomi, Sandra's sister, especially in the lullaby she sang for her unborn child, a lyrical highlight. Jessica Niles gave a spirited interpretation of the character of Sandra Seymour with her firm, clear soprano, and Katarina Bradić, as Cassandra, embodied a woman who is by turns inspired, deficient and desperate. All in all, Cassandra, the opera, succeeds in impregnating topical issues into art. Its music, along with the themes it addresses, resonates as you walk past the European Parliament in Brussels where huge posters bear witness to the most current concerns: the Russian invasion of Ukraine and a desired climate neutrality by 2050. A goal that, for all its good intentions notwithstanding, with the question marks you can place on politics that are not or not sufficiently able to cope with crises, are probably not going to be met. And 2050 is already too late. We hear the unheard voices and the sound of melting ice converge in a roaring silence. Cassandra, La Monnaie, Brussels, 10 September 2023 (world premiere) Music - Bernard Foccroulle Libretto - Matthew Jocelyn Kazushi Ono - Conductor DIRECTION Marie-Ève Signeyrole - Director, Video Artist Fabien Teigné - Set Designer Yashi - Costume Designer Louis Geisler - Dramaturgy CAST Katarina Bradić - Cassandra Jessica Niles - Sandra Susan Bickley – Hecuba, Victoria Sarah Defrise - Naomi Paul Appleby - Blake Joshua Hopkins - Apollo Gidon Saks Priam, Alexander Sandrine Mairesse - Stage Manager Lisa Willems - Conference Presenter - Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed