|

In this time of year, when hibernation tendencies seem to take over, I respond to the music of Beethoven in the most starkest of ways. Be it string quartets, piano sonates or symphonies, Beethoven's music is a road to spring and an answer to questions I didn't even know I had. When it comes to Beethoven I'm not so much of a completist; Karajan and Toscanini are not in my symphony cycle collection for instance. Depicted below are the symphony cycles that are, currently, on my shelves. On the birthday of Ludwig this is a quick inventory of them: Roger Norrington - The London Classical Players (studio 1986-88): Refreshing when I first heard it. Transformed Beethoven from a self-confident man into a man full of doubts who was, literally, on the run. As if he had to catch the last train. The more I listened to it, the more Norrington's obsession with Beethoven's metronome markings and aversion to string vibrato shone through. At the expense of my listening experience. Jos van Immerseel - Anima Eterna (live 2005-2007): The term Sturm und Drang couldn't be more appropriate than for these versions of Beethoven's Mighty Nine. This is Beethoven the revolutionary, fighting the musical consensus of his time. I saw this orchestra playing the 7th and the 8th symphony. It squeaked, creaked and sighed. This was not a majestic Beethoven but a Beethoven who was not afraid to get his hands dirty. During the concert there was a resemblance, not with another classical orchestra or another piece of classical music but with Jimi Hendrix. An artist who was not only fighting with musical boundaries but also with the instrumental means that were at his disposal. With the raw, abrasive sound of violins, wood wind and brass producing their own acoustic feedback, dating from a time before the invention of amplified sound and speaker cabinets, Immerseel and Anima Eterna pushed Beethoven out of his comfort zone and did him justice as one of the most groundbreaking composers that ever was. Theories about historical performance practices rarely convince. The music has to do that and it does here in a superb way. Frans Bruggen - Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century (studio & live 1988-1997): Another historical performance Beethoven. Sounds much more mature (not necessarily a virtue) than Immerseel. With Bruggen, Beethoven is less of a revolutionary and more an arrived man. Has the best version of the 9th symphony with period instruments I've heard. Herbert Blomstedt - Staatskapelle Dresden (church 1976-1980): One of my first cycles because of its low price. A good buy for your buck: good sound and well executed. With Blomstedt, Beethoven is someone who won't upset anyone. Decent but this readings stay a bit on the dull side of things. André Cluytens - Berliner Philharmoniker (studio 1958): For a long time my favorite cycle. In good 50's sound. As in his Wagner recordings, Cluytens is a conductor who mostly lets the music take care of itself. Like Clemens Krauss, André Cluytens gives me the feeling that the music can't be played in any other way. His approach is organic, has nothing artificial in it, and the result is completly self-evident. Carl Schuricht - Paris Conservatoire Orchestra (studio 1957-58) From the same era as Cluytens comes another favorite of mine. Having said that: this cycle is in the suitcase for the proverbal desert island. In the field of different approaches (HIP or modern) and their underlying philosophies, Schuricht does not seem to care (too much) about the choice of given instruments. His French conservatory orchestra plays with French-style woodwind and brass, making this cycle sound different than any other. It's not an objection at all. Schuricht's direction is to the point, with a keen ear for detail, and he does justice to Beethoven the revolutionary. With modern instruments in a musical delivery that unites the vibrant of HIP and the grandeur of the romantics this is, despite the mono sound for symphonies 1 to 8, the best of both worlds. Osmo Vänskä - Minnesota Orchestra (studio 2004-2006): I bought this cycle after a concert in which conductor and orchestra played the fifth symphony (my first ta-ta-ta-taaaa live!). Perhaps the biggest letdown of the whole series of cycles that are mentioned here. Here Beethoven's symphonies are presented like collections of isolated moments, notes even, rather than coherent strings of musical ideas. Whatever Vänskä's intentions or philosophies are (the use of the Ur-text suggests a HIP-invoked approach), the result leaves me stone cold. With a modern, big orchestra sounding jumpier than the worst kind of HIP (it's plagued by a complete lack of legato), this cycle can be considered as the worst of both worlds. Christian Thielemann - Wiener Philharmoniker (live 2008-2010): As Karajan's protégee Thielemann sings in his master's voice. Majestic with tones sculpted in ivory. The beauty of all this is undeniable and sonics are spectacular but this is more a Beethoven for in the showroom than for a regular ride. Wilhelm Furtwängler - Wiener Philharmoniker / Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra / Orchester der Bayreuther Festspiele (studio & live 1950-1954): Furtwängler fares better live than in the studio but this readings (all studio except for the 2nd, 8th and the 9th) make a strong case for Furt's unmatched narrative powers. However timid by times, especially when one compares it with Furtwängler's wartime recordings, this is a cycle that never fails to make an impact. Like with his 1954 Walküre these are recordings that, despite my initial reservations (mainly about slow tempi), are well worth coming back to . Stanisław Skrowaczewski - Saarbrücken Radio Symphony Orchestra (studio 2005-2006): From a box of recordings that contains as much as complete symphony cycles of Bruckner, Brahms and Schumann comes the next Beethoven cycle of this list. The Bruckner of Stanisław Skrowaczewski is legendary, it was a calling card that made me curious towards other recordings of the Polish-American conductor-composer, and it is almost inevitable that it's with Bruckerian eyes that I look at this Beethoven. The characteristics of Skrowaczewski's Bruckner approach seem indeed to shine through in his Beethoven. (Or perhaps I better say that his approach makes Beethoven and Bruckner brothers, be it from different eras.) This is Beethoven with the knowledge of Bruckner coming behind him. Despite its romantism Skrowaczewski's Beethoven doesn't suffer from sentimentality. Its tempi are swift (for instance the opening movement of the 5th is faster than Carlos Kleiber on his famous recording for DG and on par with Frans Bruggen's performance on period instruments, in the opening of the Eroica he is almost 3.5 minutes faster than Thielemann). Not that timings matter much because more important is the fact that the tempi feel completely natural. As always with Skrowaczewski they feel right. In a conducting style that's free of mannerism, it does fully justice to the Wagnerian idea of the orchestra as an entity that has to be capable of depicting everything that is in nature. Skrowaczewski has an ear for detail that reflects years of dedication and a full understanding of the role every single instrument has in that organic machine. With that rare quality to bring out opposites together in a non-conflicting way, Skrow's Beethoven is weighty yet light, purposeful yet free, sharp with soft edges and dark yet colorful. Flying on strings of desire because, as with his Bruckner (and his approach in general), for Skrowaczewski the strings are the beating heart of the orchestra. In this respect you can call him the anti-Solti ("concentrate on the brass and woodwinds and leave the strings to it"). It results in a cycle, lushful in sound, that's ranked at the top of my list of modern Beethoven cycle recordings. Riccardo Chailly - Gewandhausorchester (Gewandhaus zu Leipzig 2007-2009): For endeavours in high tech sound one can always rely on the recorded output of Riccardo Chailly. Chailly's Beethoven cycle is one - it won't come as a surprise to anyone who knows his Mahler and Bruckner cycles - in glorious HiFi. In his reading Chailly takes note of Beethoven's metronome markings, to the border of sounding obsessed by them. This is Beethoven, swift and by times rushed, that led his head speak more than his heart. A Beethoven that does want to prove something - he works his way up into a world in which daddy Haydn serves both as a source of inspiration and as a reason for revolt - but here the composer (a full-blooded romantic according to E.T.A. Hoffmann) keeps himself when it comes to making firm statements down to earth. This is, despite the historically informed tempi, very much Chailly’s Beethoven. He derives the gorges of the human soul not from the penetrating insights of life itself but from the novelle that is in the suitcase for a holiday in the sun. He flashes you by, risking a speed ticket, with a beautiful woman in the passenger seat. Here, the heart's passions do not lead to worldly insights, but are translated into making the blitz in front of crowded terraces where he drives by in a whisper, inadvertently emphasising that for that carefully served moment of nochalante charm, he stood in front of the mirror all morning. This Beethoven is, it will be clear, not pregnant with profound expression. In these recordings Chailly once again testifies to the consciousness of the modern conductor (note: everyone after Karajan is modern) who considers the living room just as much, if not more, as his stage than the concert hall. Just like his symphony cycles of Mahler and Bruckner, Chailly's Beethoven swims around in a benevolent bath of sound. But what works so well in Mahler - the unfolding of a broad tapestry of timbres – works a lot less with Ludwig: indulging in sonority. An over-sanitized approach puts Beethoven behind the window of the showroom. Here, the gloss of the blister packaging hides the view on the narrative. The storm in the Pastorale is rather a special effect from the Disney studios, we look at it in wonder and admiration but feel no need to take shelter: instead of being in earthly nature we are on a holodeck of the Starship Enterprise. The first two symphonies benefit the most from this approach. Arriving at the third, the groundbreaking Eroica, Chailly’s obsession for Beethoven’s metromone markings deprives us of an all too profound view on the revolutionary character of the piece. Bathed in the delights of modern stereo and the for this occasion somewhat too smooth working machine that is the Leipzig Gewandhausorchester – the musical delivery could have cracked more, could have taken a bit more of a breath and could have added more gravity to the lyrical lines - the drifts of Beethoven are to a good extent lost in favour of making good grace. The 2nd and a voracious 9th (that clocks in at just 62 minutes!) are my (current) favorites of a cycle in which Chailly gives us a historically informed Beethoven with a modern orchestra. A cycle for which a lot can be said but I will not trade the mono-Schuricht for this venture in crisp & clear stereo. - Wouter de Moor

2 Comments

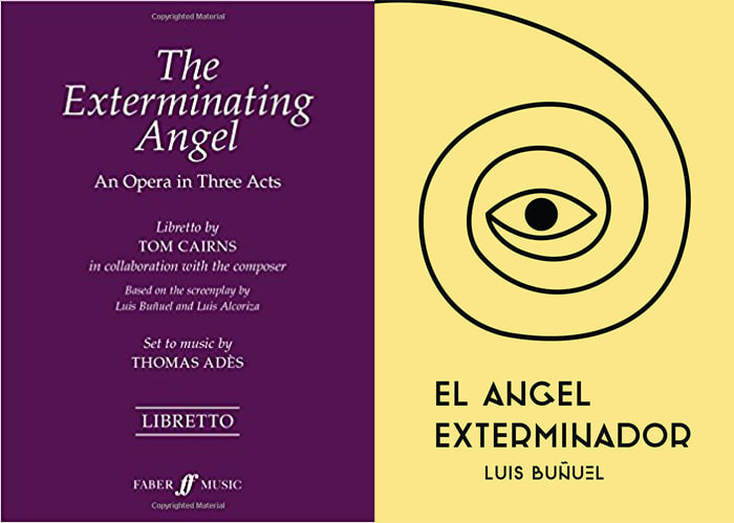

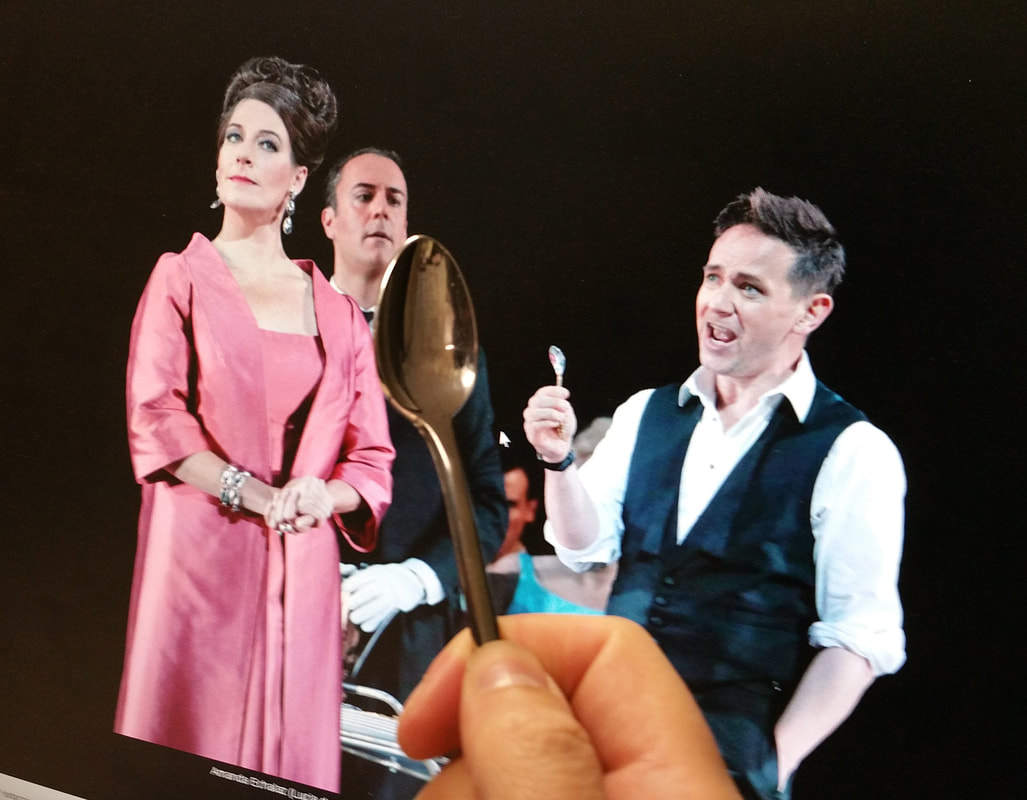

The Exterminating Angel of Thomas Adès: a copious meal on the highway to hell Imagine you're in a room where you can't get out. At every attempt to leave it you walk against a wall. Not a physical but a mental wall. And you are not able to destroy it. As a prisoner of your own mind who, once thrown back on yourself, shows that your level of civilization lives only on in the most superficial kind of ways, you end the copious meal with which it all began in an impressive degeneration fest. A visit to hell. Welcome to The Exterminating Angel. MOVIE & OPERA In 1962 Luis Buñuel made The Exterminating Angel. A film about a group of people who, after a dinner at a mansion, can for reasons unclear no longer leave the room. More than fifty years later, Thomas Adès turns that story, with a libretto by Tom Cairns based on the film, into an opera - a collaboration of the Salzburg Festival, the London Royal Opera House (Covent Garden), the New York Metropolitan Opera and the Royal Danish Opera. Luis Buñuel, himself a lover of opera (he used the music of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde in Un Chien Andalou & L'Age d'Or), makes the leap from the screen to the opera house. Seeing the result of this in a movie theater - the first time I’ve seen an opera in a cinema – is kind of going full circle. Thomas Adès captures the world of The Exterminating Angel - in which the human condition, social criticism and absurdism find each other in a dark, baroque narrative - with the energy of challenging music that pushes the story forward. It says something about the narrative power of his tight yet transparent orchestrated score that the inability of the guests to do something about their situation does not get bogged down in musical stagnation. With the prominent sound of an Ondes Martinot, an early electronic musical device, a steampunk synthesizer, and 1/32nd violins, whose sharp sound puts you in the shower of Hitchcock's Psycho, Adès delivers an uncanny atmosphere; an appropriate soundtrack for a horror fairy tale. NOTES FLYIN' HIGH The demands from Adès on the vocal abilities of his singers are considerable and for Audrey Luna (as Leticia) he even reserves the highest note ever sung in the history of the New York Metropolitan (the A above the high C). The effort that has to be put into the vocal delivery is audible and the result can sound a bit strident by times. On those occasions, when the notes seem to escape their melodies and the eloquence of the sung words seem to suffer on behalf of vocal acrobatics, Thomas Adès seems to push his singers too much. I emphasize the word 'seems' here because also Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss have been accused of composers-cruelty toward their singers and we would not like to be without Tristan or Elektra nowadays. Perhaps instruments catch up more easily with musical innovations than voices do. In the score, which has more ear for the tragic than the comical aspect of the story, the challenging harmonies effectively express the profound degeneration of the guests. It has to be seen whether The Exterminating Angel will become a repertoire piece, will be performed more often, and, in the hands of musicians and singers (and theatre makers), can ripen and gain in significance. In the mean time we'll have this fascinating and powerful production. I don't hear it right away, but in the role of the doctor, John Tomlinson - according to himself - has Wagnerian vocal lines. The dark brown voice and slow legato with which he made a furore in Bayreuth as Wotan once again impress here, although it must be noted with regard to Wagner that his vocal lines here are, especially in the first part, cut off from the rhythm of the spoken word. Wagner was attached to the tempo of the spoken language for the tempi to be retained in his music. A considerable part of the vocal lines that Adès has written for the doctor drags. As if Tomlinson, as if he were a stutter, had to speak his words very slowly in order to remain intelligible. In the rest of the cast, mezzo-soprano Alice Coote (who also sang in Thomas Adès’ "The Tempest") is Leonora Palma, a woman with a crush on her doctor. The countertenor Iestyn Davies plays the arrogant, vain aristocrat Francisco de Ávila, who does not want to stir his coffee with a teaspoon, and Joseph Kaiser is the lord of the mansion. Rod Gilfry sings with a warm baritone conductor Alberto Roc and Sally Matthews, Sophie Bevan and Frédéric Antoun make as respectively Silvia de Ávila, Beatriz and Raul Yebene their debut for the Metropolitan. SHEEPS & SALT The night becomes morning and the morning turns into another day. There is a bear in the kitchen and there are sheep walking around. The dinner party slaughters a lamb to satisfy their hunger and there are, attached as they are to their entitlement and privilege, complains about a lack of salt. Someone has died, followed by the suicide of the love couple Beatriz and Eduardo. Perhaps more people will have to die. Perhaps the situation requires the sacrifice of another human being. Maybe a conductor, because who cares about a conductor more or less? It is one of the two references to Adès himself. A piece of music by the composer Hades is requisted. Besides an allussion to the name of Adès, it’s also the opposite of the name Paradisi, a composer whose piece of music is played in both film and opera. A moment that can be seen as the beginning of the deadlock. This piano piece ("Oh, if we only had a harpsichord," someone says) throws the key into the mental lock and opens it again - when it is played again - as the dinner party succeeds, by reconstructing earlier events, to find their way out. But even this re-enactment, with which the party succeeds in escaping, does not bring liberation. Once outside, the guests – accompanied by dark chords of doom – are enclosed by the gate along which they have left the room and the manor house. THE DANCE OF THE DOOMED Adès largles the piece with a few references to music from others, the Viennese waltzes of Johann Strauss and a quote from Der Rosenkavalier - a reference to the 19th century Austrian domination of Mexico, the place where Buñuel shot his film. In addition to the walls of thought in which the company keeps itself captive, the fragments of these cosy Viennese waltzes are like a wall of music, an invitation to stay inside. Buñuel was not into explaining his films in depth, but he noticed that the film was not so much about mankind as it was about the bourgeoisie. "If I had shot the film in Paris instead of Mexico, I would have put cannibalism in it," Buñuel once said. He could not have expressed his dedain for the bourgeoisie (and the French bourgeois mentality) in a more gloomier way. There are people outside who want to free the company from the mansion. Without avail. There is a child in the crowd whose mother is inside. It gets a slap in its face from a priest. There is riot police to maintain order. The elite, the police and the church, Buñuel had unfinished business with them. The Spanish civil war and its traumatic outcome, Franco and the establishment supporting him, would be a lifelong source of anger and inspiration for the man from Calanda. Can we get emotionally attached to people whose motives we cannot understand? Are we able to care about what happens to them, or does the absurdity of their fate just bring a smile to our face? An incomprehensible story in the world of opera does not have to be an obstacle to make a piece a success (it never hurted Der Zauberflöte). You don't have to understand The Exterminating Angel in full to appreciate it (wanting to understand everything was, according to Buñuel, above all a characteristic feature of the bourguoisie). But it is recommended to see the movie before you attend the opera. It makes a surreal viewing and listening experience less incomprehensible. It gets you in touch with the source material which may make you appreciate the opera more. Habituation is often the preliminary stage of appreciation. The opera leaves an indelible impression with humour as black as the early night in the dark days before Christmas. With the cinema, in this case the picturesque Tuschinski theater in Amsterdam, as a perfect host. The Exterminating Angel is a bold and daring opening of a season in which the New York Metropolitan mainly performs operas from the (well-known) French and Italian repertoire. Operas that can be seen in the cinema this season. Programme 2017 / 2018:

2017 Hansel and Gretel (Humperdinck) 12-24 2018 Tosca (Puccini) 1-27 L’elisir d’Amore (Donizetti) 2-10 La Boheme (Puccini) 2-24 Semiramide (Rossini) 3-10 Cosi fan tutte (Mozart) 3-31 Luisa Miller (Verdi) 4-14 Cendrillon (Massenet) 4-28 |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed