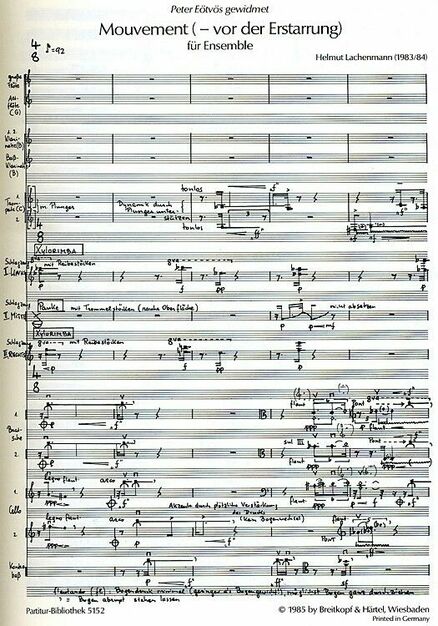

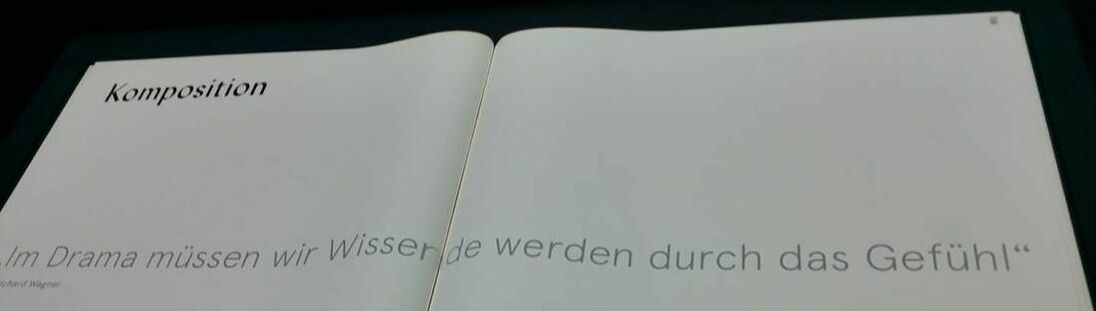

'Mouvement' by Helmut Lachenmann sandwiched between two Mozart symphonies Do not pay attention to the music. Keep on talking. Thank you. There are hardly any more cynical words imaginable to urge the audience to be silent. However, the request is anything but cynical, it must be taken literally. It serves as an introduction to Erik Satie's Vexations. Music d'Ameublement. Music while you're doing something else. Music that may be regarded as a forerunner of elevator music and noise. Music that tonight has to prepare the audience for the piece Mouvement by Helmut Lachenmann. A piece that, sandwiched between Mozart's symphonies 39 and 41, should lead the listener to a new world of sound, perhaps even to a new way of listening. A listening experience in which every sound can be music. A listening in which the listener himself can check the boundaries of what he considers music, what he wishes to consider music. An aural journey that will go from the first Viennese school to the acoustic techno, Musique Concrète Instrumentale, of Helmut Lachenmann. A journey that can perhaps best be described as a descent into modern Nibelheim - a place where the consumer society has taken the place of nature. Perhaps a combination with the music of Gustav Mahler would have been more appropriate. Where Mahler tried to capture the essence of nature in his symphonies, one can say with Lachenmann, and this is mere a listener's opinion, that he aims for the world after nature. The world of the industrial revolution and its outcome, the modern consumer society. Lachenmann creates sound images that must point the nowadays listener to the essence of their desire to consume. He aims his arrows at instant satisfaction and his music certainly does not have an obligation to please. Instead of ecstasy and entertainment Lachenmann seeks danger, stirred by alienation, frustration and confusion - a danger every composer should strive for in our time, The real danger for him comes from the listener who wants to be entertained and the composer who wants to please. In an era of magic conveniently available at the touch of a button, new music should on principle represent something akin to 'danger'... There is this story about Ennio Morricone, told by Lachenmann, who did not want suites from Once Upon A Time In The West to be played on the same evening as Lachenmann's Mouvement. Despite Morricone's objections, Morricone and Lachenmann shared the same programme, with both composers sitting side by side during the concert. Aware of what the famous film composer thought of him, Lachenmann (a great admirer of Morricone by the way) didn't dare to say anything to the Italian maestro. What Morricone, the good, found so bad & ugly in Lachenmann's music, the story doesn't tell and it won't become clear tonight either. Because that music turns out to be exciting and by no means as inaccessible as might have been feared beforehand. For the creation of his music, Lachenmann doesn't use other kind of instruments than Mozart had at his disposal. Where Mozart sought innovation in his orchestration, for example fitting in a clarinet where an oboe was more in the conventional line of expectation (in symphony 39), Lachenmann takes other, more extreme, paths. He ignores the academic rules on how to play an instrument and moves aside classical harmony and counterpoint. Thus oboes are used as percussion instruments, the bow of cello and double bass does not play only the strings but also the body and tuning pegs; a kettledrum is put upside down. With something as anachronistic as a classical orchestra, he emancipates sound into music. He looks at modern times with classical means - like making an engraving of a computer screen. With the result, in which every sound can ultimately be music, what is heard must also be felt. It is an awareness through sound. A music that leads to thinking, whether or not about concrete topics. Music that takes you back in your thoughts, makes you aware of those thoughts without the need to formulate or express them. It leads to a kind of "knowing through feeling". It seems to be both inspired by Wagner as well as revolting against it. Over the rainbow bridge that leads to Valhalla, Lachenmann lays a grey carpet. He covers the opulent colours of Romanticism with shades that are (much) less seductive but the question whether there is music in his soundscapes does not come to mind. For example, the confusion that can arise from a piece like Heinz Hölliger's string quartet - am I listening to randomly chosen notes or a composition? - stays here at great distance. Lachenmann's acoustic techno (it would lend itself well for an unplugged session with Nine Inch Nails or Mike Patton's Fantomas) sounds too structured for that, too comfortable also. Lachenmann's music is no less structured than the classical music that preceeds it, but the ordering effect of his music - which is able to sharpen the mind, to make you feel smarter (if only by the power of suggestion) - is less compelling than with Mozart. It appeals more to one's own interpretation. You have to feel it. The resonating of the air. The sine waves that land on your eardrums. Attending it live is (even more than with the classical repertoire) a necessary condition for possible appreciation. The Jupiter symphony can sound good on your smartphone, Lachenmann not. His music is for modern ears an invitation to link image to sound. An invitation that, once accepted, turns the head into a space that one can travel in. The fact that this journey leads less far into unknown territory than was previously thought says something about the emancipation process that the dissonant has gone through over time. Film music makes ample use of it. Of note clusters that are used purely for their suggestive power. The contrast that lies in Lachenmann's work - catching the modern world with classical means - makes his music, at least the music I became acquainted with tonight, a fascinating experience. (It seems that nothing offends Lachenmann more than saying that you find his music interesting, so I will mark my words here.) It is an experience in which tuning the instruments prior to a Mozart symphony becomes part of the programme. How does one listen to Mozart when one have just breathed the air of a new world? Does the introduction to new music provide a new perspective on old music? Tonight's concert did not give an unambiguous answer to that. Before the intermission I felt some reservations about the performance of Mozart's 39th symphony. Under the baton of Francois-Xavier Roth, the rendition of Les Siecles sounded a bit stiff. As if the piece was a bit underrehearsed. After the break, after Lachenmann, the Jupiter and the Overture Nozze (as encore) sounded significantly better. But that was simply because of the performers and (probably) because of the compositions themselves. Also in music of centuries ago one can, every performance again, stare into a new world. For example in that superbe Adagio of the Jupiter symphony. A sound carpet that is like a sky with clouds in which one can see faces appear, again and again, the longer one looks at it. It are meandering sounds that are an invitation to fill in the silence between the notes with one's own panoramas. In that Adagio, music automatically becomes a landscape in which one can let the mind wander. Here Mozart reached out a hand to his 20-21th century colleague. His music became here, as the musical companion of Lachenmann's Mouvement, a sound in which the spirit was encouraged to go on a journey of discovery itself. It was as if the two composers, each a child of their own time, met on the banks of the IJ and engaged in conversation. Muziekgebouw aan 't IJ - 12 January 2019 Les Siècles orchestra François-Xavier Roth conductor Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 39 Helmut Lachenmann Mouvement Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Nozze di Figaro - overture (encore) - Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

|

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed