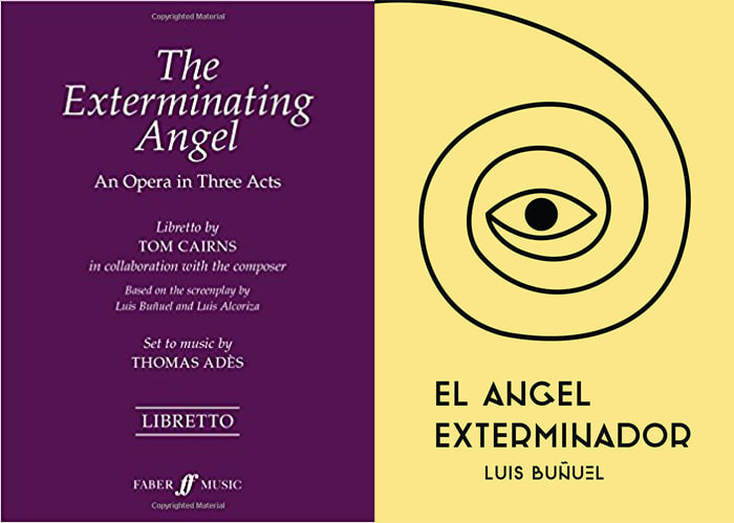

The Exterminating Angel of Thomas Adès: a copious meal on the highway to hell Imagine you're in a room where you can't get out. At every attempt to leave it you walk against a wall. Not a physical but a mental wall. And you are not able to destroy it. As a prisoner of your own mind who, once thrown back on yourself, shows that your level of civilization lives only on in the most superficial kind of ways, you end the copious meal with which it all began in an impressive degeneration fest. A visit to hell. Welcome to The Exterminating Angel. MOVIE & OPERA In 1962 Luis Buñuel made The Exterminating Angel. A film about a group of people who, after a dinner at a mansion, can for reasons unclear no longer leave the room. More than fifty years later, Thomas Adès turns that story, with a libretto by Tom Cairns based on the film, into an opera - a collaboration of the Salzburg Festival, the London Royal Opera House (Covent Garden), the New York Metropolitan Opera and the Royal Danish Opera. Luis Buñuel, himself a lover of opera (he used the music of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde in Un Chien Andalou & L'Age d'Or), makes the leap from the screen to the opera house. Seeing the result of this in a movie theater - the first time I’ve seen an opera in a cinema – is kind of going full circle. Thomas Adès captures the world of The Exterminating Angel - in which the human condition, social criticism and absurdism find each other in a dark, baroque narrative - with the energy of challenging music that pushes the story forward. It says something about the narrative power of his tight yet transparent orchestrated score that the inability of the guests to do something about their situation does not get bogged down in musical stagnation. With the prominent sound of an Ondes Martinot, an early electronic musical device, a steampunk synthesizer, and 1/32nd violins, whose sharp sound puts you in the shower of Hitchcock's Psycho, Adès delivers an uncanny atmosphere; an appropriate soundtrack for a horror fairy tale. NOTES FLYIN' HIGH The demands from Adès on the vocal abilities of his singers are considerable and for Audrey Luna (as Leticia) he even reserves the highest note ever sung in the history of the New York Metropolitan (the A above the high C). The effort that has to be put into the vocal delivery is audible and the result can sound a bit strident by times. On those occasions, when the notes seem to escape their melodies and the eloquence of the sung words seem to suffer on behalf of vocal acrobatics, Thomas Adès seems to push his singers too much. I emphasize the word 'seems' here because also Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss have been accused of composers-cruelty toward their singers and we would not like to be without Tristan or Elektra nowadays. Perhaps instruments catch up more easily with musical innovations than voices do. In the score, which has more ear for the tragic than the comical aspect of the story, the challenging harmonies effectively express the profound degeneration of the guests. It has to be seen whether The Exterminating Angel will become a repertoire piece, will be performed more often, and, in the hands of musicians and singers (and theatre makers), can ripen and gain in significance. In the mean time we'll have this fascinating and powerful production. I don't hear it right away, but in the role of the doctor, John Tomlinson - according to himself - has Wagnerian vocal lines. The dark brown voice and slow legato with which he made a furore in Bayreuth as Wotan once again impress here, although it must be noted with regard to Wagner that his vocal lines here are, especially in the first part, cut off from the rhythm of the spoken word. Wagner was attached to the tempo of the spoken language for the tempi to be retained in his music. A considerable part of the vocal lines that Adès has written for the doctor drags. As if Tomlinson, as if he were a stutter, had to speak his words very slowly in order to remain intelligible. In the rest of the cast, mezzo-soprano Alice Coote (who also sang in Thomas Adès’ "The Tempest") is Leonora Palma, a woman with a crush on her doctor. The countertenor Iestyn Davies plays the arrogant, vain aristocrat Francisco de Ávila, who does not want to stir his coffee with a teaspoon, and Joseph Kaiser is the lord of the mansion. Rod Gilfry sings with a warm baritone conductor Alberto Roc and Sally Matthews, Sophie Bevan and Frédéric Antoun make as respectively Silvia de Ávila, Beatriz and Raul Yebene their debut for the Metropolitan. SHEEPS & SALT The night becomes morning and the morning turns into another day. There is a bear in the kitchen and there are sheep walking around. The dinner party slaughters a lamb to satisfy their hunger and there are, attached as they are to their entitlement and privilege, complains about a lack of salt. Someone has died, followed by the suicide of the love couple Beatriz and Eduardo. Perhaps more people will have to die. Perhaps the situation requires the sacrifice of another human being. Maybe a conductor, because who cares about a conductor more or less? It is one of the two references to Adès himself. A piece of music by the composer Hades is requisted. Besides an allussion to the name of Adès, it’s also the opposite of the name Paradisi, a composer whose piece of music is played in both film and opera. A moment that can be seen as the beginning of the deadlock. This piano piece ("Oh, if we only had a harpsichord," someone says) throws the key into the mental lock and opens it again - when it is played again - as the dinner party succeeds, by reconstructing earlier events, to find their way out. But even this re-enactment, with which the party succeeds in escaping, does not bring liberation. Once outside, the guests – accompanied by dark chords of doom – are enclosed by the gate along which they have left the room and the manor house. THE DANCE OF THE DOOMED Adès largles the piece with a few references to music from others, the Viennese waltzes of Johann Strauss and a quote from Der Rosenkavalier - a reference to the 19th century Austrian domination of Mexico, the place where Buñuel shot his film. In addition to the walls of thought in which the company keeps itself captive, the fragments of these cosy Viennese waltzes are like a wall of music, an invitation to stay inside. Buñuel was not into explaining his films in depth, but he noticed that the film was not so much about mankind as it was about the bourgeoisie. "If I had shot the film in Paris instead of Mexico, I would have put cannibalism in it," Buñuel once said. He could not have expressed his dedain for the bourgeoisie (and the French bourgeois mentality) in a more gloomier way. There are people outside who want to free the company from the mansion. Without avail. There is a child in the crowd whose mother is inside. It gets a slap in its face from a priest. There is riot police to maintain order. The elite, the police and the church, Buñuel had unfinished business with them. The Spanish civil war and its traumatic outcome, Franco and the establishment supporting him, would be a lifelong source of anger and inspiration for the man from Calanda. Can we get emotionally attached to people whose motives we cannot understand? Are we able to care about what happens to them, or does the absurdity of their fate just bring a smile to our face? An incomprehensible story in the world of opera does not have to be an obstacle to make a piece a success (it never hurted Der Zauberflöte). You don't have to understand The Exterminating Angel in full to appreciate it (wanting to understand everything was, according to Buñuel, above all a characteristic feature of the bourguoisie). But it is recommended to see the movie before you attend the opera. It makes a surreal viewing and listening experience less incomprehensible. It gets you in touch with the source material which may make you appreciate the opera more. Habituation is often the preliminary stage of appreciation. The opera leaves an indelible impression with humour as black as the early night in the dark days before Christmas. With the cinema, in this case the picturesque Tuschinski theater in Amsterdam, as a perfect host. The Exterminating Angel is a bold and daring opening of a season in which the New York Metropolitan mainly performs operas from the (well-known) French and Italian repertoire. Operas that can be seen in the cinema this season. Programme 2017 / 2018:

2017 Hansel and Gretel (Humperdinck) 12-24 2018 Tosca (Puccini) 1-27 L’elisir d’Amore (Donizetti) 2-10 La Boheme (Puccini) 2-24 Semiramide (Rossini) 3-10 Cosi fan tutte (Mozart) 3-31 Luisa Miller (Verdi) 4-14 Cendrillon (Massenet) 4-28

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed