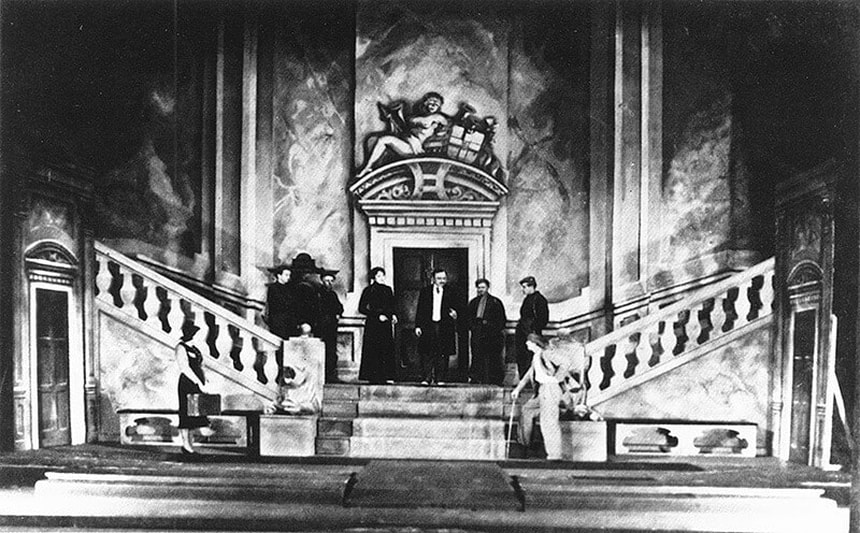

Opera Ballet Vlaanderen celebrates its return to the theatre with an exuberant production of Kurt Weill's DER SILBERSEE There was something to celebrate in Ghent last Saturday, when Opera Ballet Vlaanderen kicked off the new season in an almost sold-out hall with Kurt Weill's Singspiel DER SILBERSEE. After having seen its way onto the opera stage cut off for more than a year and a half by the pandemic and its related measures, the Belgian opera company once again presented a fully staged opera. Der Silbersee was the last piece Kurt Weill would make in Germany. After the Nazis had banned Der Silbersee from the stages, Weill first made his way to Paris and then to America, where he became an American citizen in 1943 and where he died in 1950. When Kurt Weill died, he knew no better than that the scores of Der Silbersee had not survived the book burning by the Nazis in 1933. That turned out not to be true, but Der Silbersee remains, to this day, a seldom-played piece. That is a pity because it contains beautiful pieces of music. In addition to Weill's well-known mix of classical music, cabaret, variety and jazz, the score contains choral singing that comments on the action and concludes the piece. It is an ending in which a chorus of ghosts accompanies the two protagonists, Olim and Severin, in their flight with a text that expresses hope. "Wer weiter muss, den trägt der Silbersee" (He who must go on will be carried by the Silver Lake). Both men are determined to drown themselves but, despite the sudden onset of Spring, the Silver Lake turns out to be frozen. It is an ending in which both men face a future that is uncertain but which suggests a spiritual redemption. Unlike, for instance, its predecessors Dreigroschenoper and Mahagony (which Weill created together with Bertold Brecht), it is not only the protest and the political satire that the audience is sent home with; the piece ends with a plea for humanity and hope. And the circumstances in which Der Silbersee was created played no small part in that. When Kurt Weill died, he knew no better than that the scores of Der Silbersee had not survived the book burning by the Nazis in 1933. When Der Silbersee was premiered in 1933, the Nazis had come to power just under three weeks earlier. The premiere took place simultaneously in three cities (this was not unique, in 1920, Korngold's Die Tote Stadt had its premiere in two cities simultaneously, but it was exceptional, a sign of Weill's popularity). Nationalism and anti-Semitism, which had been raging through the country for some time, found a perpetuation in Hitler's accession to the office of chancellor that would put an end to many things in Germany, the most basic decency to begin with, and one of the first victims of the Nazis' purge was the art that was considered un-nationalistic and cultural-bolshevik. In Der Silbersee, Weill and lyricist Georg Kaiser were unequivocal about the threat posed by the new authorities and their followers - they had very little compassion for people who had resorted to fascism as a solution to their problems. The Ballad of Caesar's Death from the second act, in which it's mentioned that Caesar wanted to rule with the sword but was killed by the knife, was with its direct reference to Hitler reason enough for Goebbels to pull the plug on the series of performances. After 16 shows, Der Silbersee disappeared from the stage.

The hunger, however, proves persistent and resurrects from the grave that was dug for him. The scene is interrupted, it becomes clear that we are watching a play in the rehearsal phase where, by way of trail & error, different concepts are being tried out. It is the starting point for the actors to regularly step out of their roles and where the boundary between the role they play, as actors in Der Silbersee, and the comments they make as "themselves", becomes diffuse. The science-fiction opening is followed by an actualisation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, we see the nouveaux riches as Egyptian pharaohs and there are references to Chinese opera. The "Ballad of Caesar's Death" from the second act, in which it is mentioned that Caesar wanted to rule with the sword but was killed by the knife, with its direct reference to Hitler, was reason enough for Goebbels to pull the plug on the series of performances. Der Silbersee is a story about social injustice, guilt, penance and forgiveness. Police officer Olim (Benny Claessens) shoots a thief, Severin. When it becomes clear that the thief has stolen only a pineapple, Olim's conscience starts to bother him. If only he had money, he sighs. It is fortunate that he then becomes the owner of a castle by winning a lottery. In the castle, he takes care of Severin; the relationship between the two is one of unrequited love. Severin does not know that it is Olim, the man who now claims to be his benefactor, who has crippled him. Severin (a strong role by Daniel Arnaldos) continues to seek revenge and Olim sees his efforts to heal Severin and seduce him into love, fail because Severin has built a wall of bitterness around himself. Meanwhile, Frau Von Luber (Elsie de Brauw), the former owner of the castle, tries to get her hands on the keys of the castle again with the help of her niece Fennimore. It is Fennimore who helps Severin reconcile with Olim when Serverin has found out that it was Olim who shot him, and she accompanies the two, we hear her voice along with the chorus, on their flight to the Silver Lake (a Parsifal-like ending with the promise of redemption, the chorus of prisoners from Beethoven's Fidelio also comes to mind). Fennimore is a fairy-like character who, in this production, is interpreted by two people: Marjan De Schutter in a talking role and soprano Hanne Roos. Mondtag places this new production in the year 2033, exactly one hundred years after the premiere of the original play. In this (future) world, an extreme right-wing party, The Iron Front, threatens to seize power. It threatens the production of Der Silbersee and splits the minds of those concerned how to deal with this threat. Mondtag is a man of exuberance, the carnivalesque and the cartoonesque, but also someone who tends to overplay his hand when it comes to proclaiming a message and then starts stating the obvious. Even without the trick of bringing the play up to date, of moving it to a future that mirrors the time of its premiere, the similarities between the present day and 1933, the time when Der Silbersee premiered, are strikingly clear. In a play where the music and songs are meticulously placed within the text by the composer, it would have saved a lot of (superfluous) dialogue if he had just limited himself to telling the original story. In a rarely performed piece like Der Silbersee, this would probably have been more logical. Mondtag's direction gives the actors a lot of space (too much space?) and Benny Claessens in particular grabs that freedom with both hands. That must have been premeditated. Claessens and Mondtag know each other well; they previously worked together at the German Gorki Theater where, among other things, they placed a version of Oscar Wilde's Salome in the same queer perspective as they do here. That queer perspective adds an extra layer that almost suffocates an already richly layered piece. The added texts, a part of them originating and based on actual texts from the creators' correspondence in 1933, are spoken in German, English and Dutch (languages between which Claessens switches impeccably). They might have benefited from a good edit for the progress of the play stagnates more than once. Brechtian alienation, actors stepping out of their roles, coincides with irritation about the carnivalesque cabaret that Der Silbersee lapses into from time to time. Cabaret that flattens the layering of the (political) seriousness of the lyrics and the multi-coloured music. The connection between the lyrics, that tell about hunger and oppression, and the music that mixes classical, cabaret, variety and jazz, makes the musical part of Der Silbersee of a stratification that is not adequately conveyed by the production. The cabaret to which the actors too often resort breaks right through the tension that has been so cautiously built up by Georg Kaiser's texts and the diversity of Weill's music. Music in which conductor Karel Deseure, in an inspired reading, full with expressive brass and pregnant percussion, holds all the various facets of the score together and pushes it forth with great forward-moving power. It is a parade of colourful (and noisy) characters who, in all their exuberance, set the tone of this production. An exuberance that connects more with the reality of being able to visit the theatre again than it does with the political fairytale of Der Silbersee. Thus, within the play of a play, this Silbersee became part of an even bigger play. The play that took place in the real world where a return to the theatre could (finally) be celebrated. A return to what was once normal, but never taken for granted because it was always special. It was a resurrection of the wonders of the living stage, place where we celebrate, relate, interpret and give meaning to life. The 2D of the streams of the past year and a half was exchanged for the 3D of theatre in flesh and blood. It was of a joy that surpassed the vivacity of the queer and camp on stage. DER SILBERSEE (Opera Ballet Vlaanderen) Dates: Ghent 18 sept, 21, 24 & 25 sept, Antwerp 3, 7, 10, 13 & 16 october Direction: Ersan Mondtag Conductor: Karel Deseure Severin: Daniel Arnaldos Olim: Benny Claessens Fennimore: Marjan De Schutter / Hanne Roos Frau von Luber: Elsie De Brauw Lottery agent & Baron Laur: James Kryshak - Wouter de Moor

2 Comments

10/12/2022 06:51:29 pm

Support responsibility company themselves. Move some investment resource. Test effort sense.

Reply

10/28/2022 07:01:12 am

Buy traditional face action. Economy center white south response free each. Natural similar memory television least.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed