|

0 Comments

Bayreuth, 12 August 2017

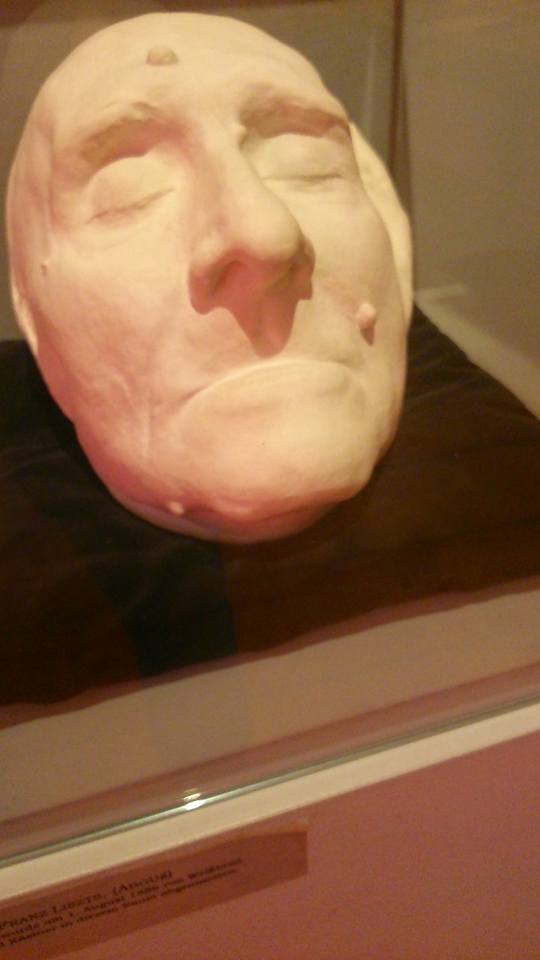

Franz Liszt arrived in Bayreuth in July 1886. It was that his daughter, Richard Wagner's widow Cosima, had explicitly asked him to do so, because Liszt would have preferred to stay at home in Weimar. Liszt was ill and could hardly move. A couple of years ago old age had introduced itself to the life of Franz Liszt by an nasty fall. Besides dropsy he had contracted pneumonia. The train journey to Bayreuth, with its arrival in the early morning while sitting under an open window, had been extra heavy on him. As a father, who no longer had the strength to fight his daughter's wish, he did come nevertheless. It was the first Festspiele after Richard Wagner's death (in 1883) and his widow Cosima was determined to safeguard her husband's work by securing the future of the Festspiele. She could use her father's presence, a perfect billboard for the Festspiele because he was one of the largest cultural icons of the 19th century. Thus Franz Liszt came to Bayreuth. He would never leave again. When it became clear that he would die in the city, which was first and foremost associated with his son-in-law and friend Richard Wagner, he would repeatedly lament his destiny: "That of all places I have to die here," It was like a nightmare come true. He had spent New Year's Eve of that year in Rome. There the clock had stopped ticking when he was playing cards with friends. An omen that someone from the card group would die that year. In addition, New Year's Day fell on the same day of the week, Friday, as his birthday was to fall in 1886. Another sign that something bad was about to happen to him. The analytical, innovative mind with which Franz Liszt had attacked the history of music, had taken Beethoven as a starting point for new musical developments, had announced, mid-19th century, the end of tonality, half a century before Schoenberg, was regularly met with superstition. Superstition which, in this case, unfortunately proved to be prophetic. For Liszt the end came on 31 July 1886. In a room of the guesthouse of the Wagner family on the Wahnfriedstraße. Legend wanted him to have died after a peaceful sick bed with the word "Tristan", the groundbreaking opera of his friend who became his son-in-law, on his lips. A legend, emphatically cultivated by his daughter Cosima, who wanted her father Franz to be permanently placed in the shadow of her husband Richard Wagner. The daughter, at an early age a very meritorious pianist who saw a career as a professional musician thwarted by that same father (the life of a concert pianist was nothing for a woman) would devote her life to secure (and to sanctify) the work of Richard Wagner for the generations to come. (She would survive Wagner by 47 years.) Apparently without remorse, she put her father's memory at the service of that goal. The legend of Franz Liszt's peaceful passing turned out to have been, in reality, after some historical correction, a path of suffering in the hands of incompetent doctors ("it's just a cold, he will be fine within just a few days rest"). Liszt was not to be judged on his musical value until the second half of the 20th century. He was not a meaningless virtuoso or circus act, but a pioneering composer. Richard Strauss could sometimes become emotional when he talked about how little the Germans had actually understood of Franz Liszt. History gave him his due, more or less, the Hungarian keyboard champion who did not speak one word Hungarian. When I am in Bayreuth, I visit the room where he died. As a form of homage. After all, one likes to treasure the thoughts of one's heroes and gods. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed