|

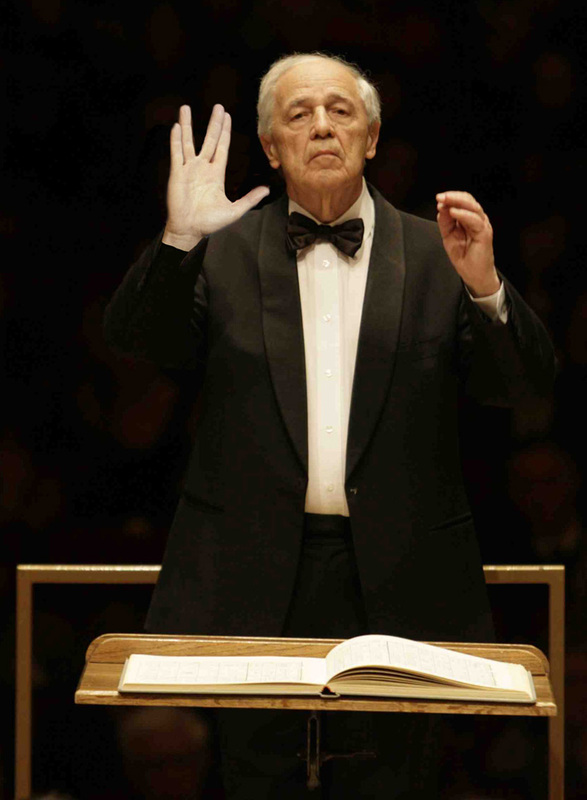

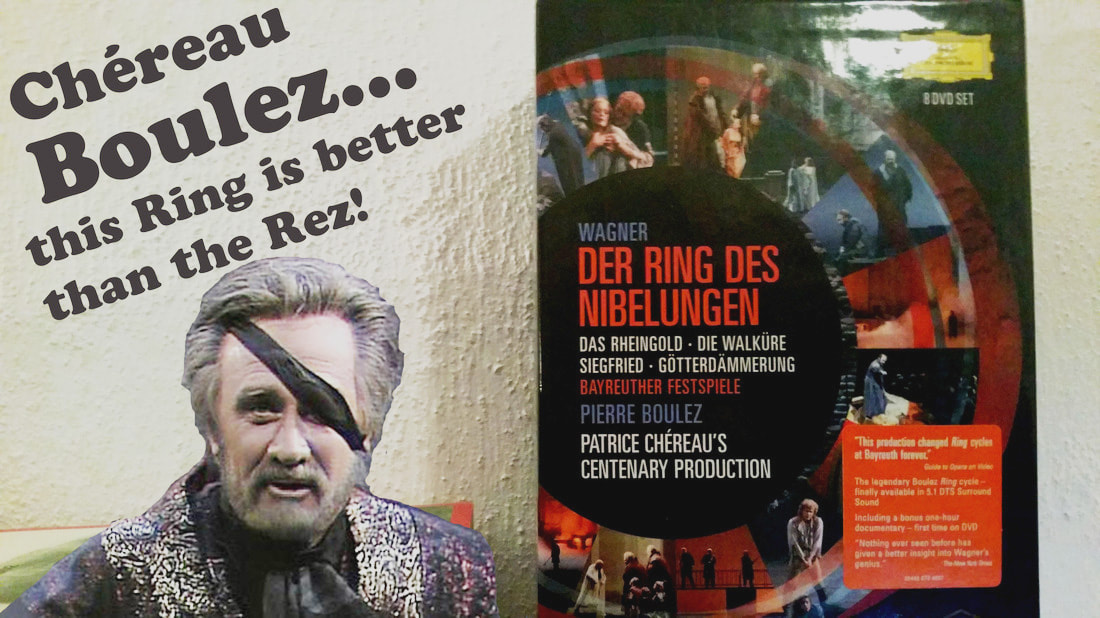

And so we start the new year. But the man I always thought would live to see 100 is not going to join us into 2016 and beyond. That's one reason to be upset, among others, because if the ones that were with us for such a long time, in life and in image, die anyway, it makes the future just a little bit more unforeseen (and insecure). With his demise the 20th century is definitely over and the 21th century has lost another burden of its past. I guess Pierre Boulez would not be unsympathetic towards that idea. Creation exists only in the unforeseen made necessary, he once said. For someone who was nicknamed “Mr. Sang Froid” his contributions to the late 19th-begin 20th century German-Austrian romantic repertoire were remarkable. It was Richard Wagner's Ring des Nibelungen that introduced me to Pierre Boulez. His reading of Wagner, swift and transparent, convinced me at once. In Wagner there is a risk to state the obvious. Then the tempi slow down and the volume increases. Not with Boulez. With him Wagner's music is like a cathedral drawn in fine lines that gives us a view of the structure that lies underneath – a sense for superb architecture. His Wagner was alive and breathing, as was his Mahler and Bruckner. For someone whose nicknames went from “Mr. Sang Froid” to “The high priest of modern music”, his contributions to the late 19th-begin 20th century German-Austrian romantic repertoire were remarkable. From his performances in Bayreuth I have Parsifal (1970), Der Ring des Nibelungen (Cds from 1976 and 1977 and DVDs from 1980) and a performance from Tristan und Isolde from 1969 (recorded in Osaka Japan, this is a Bayreuth on Tour-production). The 1976 Ring is special. It was Boulez' take on the music together with Chéreau's regie that was too much of a breach in the tradition of Wagnerian opera performances than the audience was willing to accept for this centenary Ring. Among booing and other noisemaking, that indicates that a considerable part of the audience is less than amused, there is in Siegfried someone from the anti-Chereau contingent who brings his own whistle. In the saddest tradition of the Jockey Club, a prestigious elite club that terrorized Wagner's Paris premiere of Tannhäuser in 1861, he plays along when Siegfried blows on his own makeshift reed in the second act. There is a frenzy that surrounds these performances and it makes listening to them both exciting and harrowing. A frenzy that I miss, perhaps odd, in the recordings from 1977 (the 1980 performances on DVD were, of course, recorded without audience). With Patrice Chéreau already dead in 2013, both director and conductor of this legendary Ring are no more. It was in vain that Boulez asked Chéreau to look into Parsifal. But Chereau couldn't connect to this opera and declined. Alas. It was Boulez who made a case for Parsifal for me. Because for a long time I had a pretty hard time digesting Wagner's last opera. I've read about the life-changing event the Knappertsbusch-1951-performance must have been but from the long first act (which can be slower-than-slow) to the intoxicating end of the third act, I felt, in contrary to all those other Wagner operas (from Holländer on), an uninvited guest at a party where only initiates were welcome. It was not before I heard Boulez' take on Parsifal, with his swift tempi, that this opera started to make sense to me.

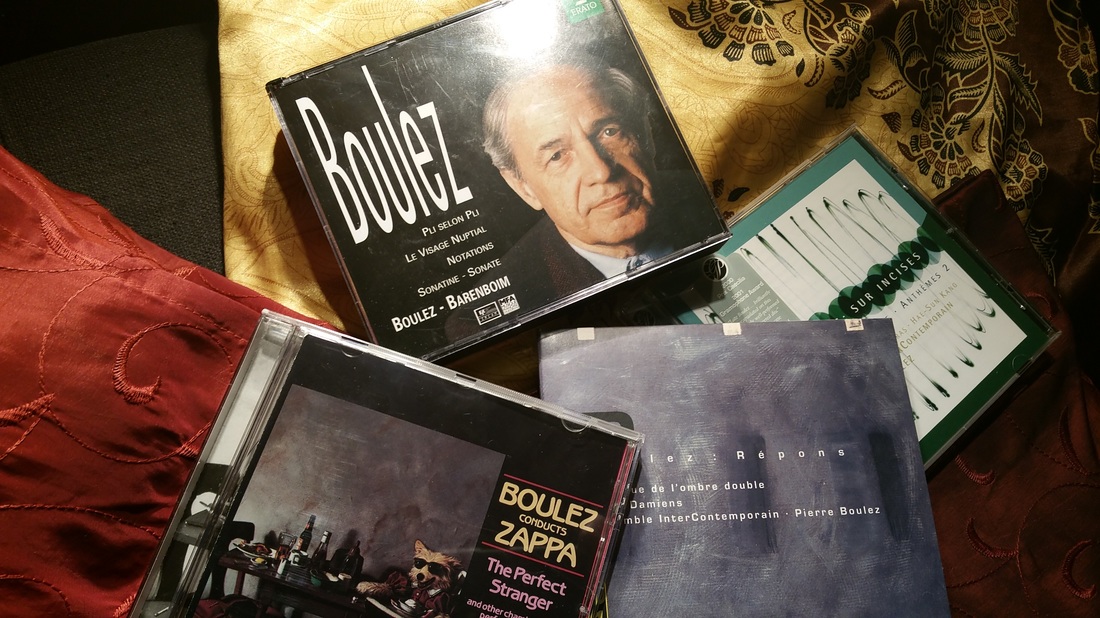

The last time I saw Boulez was in Amsterdam, the Concertgebouw. It was Januar 2011, now exactly 5 years ago and he conducted Mahler 7 on that occasion. He linked Gustav Mahler to Six Pieces for Orchestra by Anton Webern. By programming it that way, and by his crystal clear reading, he showed us Mahler as a 20th century composer. Away from the 19th century - away from Bruckner and Brahms. He refreshed my view on Mahler like he did with Wagner before. Boulez was a door to new music. Be it as an interpreter of compositions by Frank Zappa (one way to describe Zappa's efforts in modern composition is "Boulez-lite with a beat", I leave it to the academics to what degree that description is apt) or by his own compositions which I came to know and appreciate pretty late in my music-loving life (with Pli Selon Pli, Le Visage Nuptial, Répons and the hauntingly beautiful Cummings ist Der Dichter as current favorites). Like all great art, Boulez' music is accessible on different levels. You don't have to be a scholar in musical theory in order to appreciate it. Put on a record and just let it happen. It will grow on you (often habituation precedes appreciation). The only thing you need is a body and a pulse (I think Wagner said something like that when he was confronted with concerns about the accessibility of Tristan und Isolde - 4 hours of heavy chromatic music in an opera without any arias). And ears that grew up with movie soundtracks know how to deal with dissonances and enharmonic sounds a lot better than you will, perhaps, give them credit for. Pierre Boulez had a good taste for polemic but for me he was, first and foremost, a bridge to new worlds of sound. For that I'm grateful. Merci maître.

2 Comments

MusicFan

12/31/2017 07:04:37 pm

I'm glad I just recently discovered your website. As a metal fan who is starting to discover classical it is nice to see the two linked as you do. For a person who is new to Boulez, where would you say I should start? I like energy and power.

Reply

1/1/2018 06:09:55 pm

Thanks for your comment. For me the orchestral versions of Notations were good starting points for the music of Pierre Boulez.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed