|

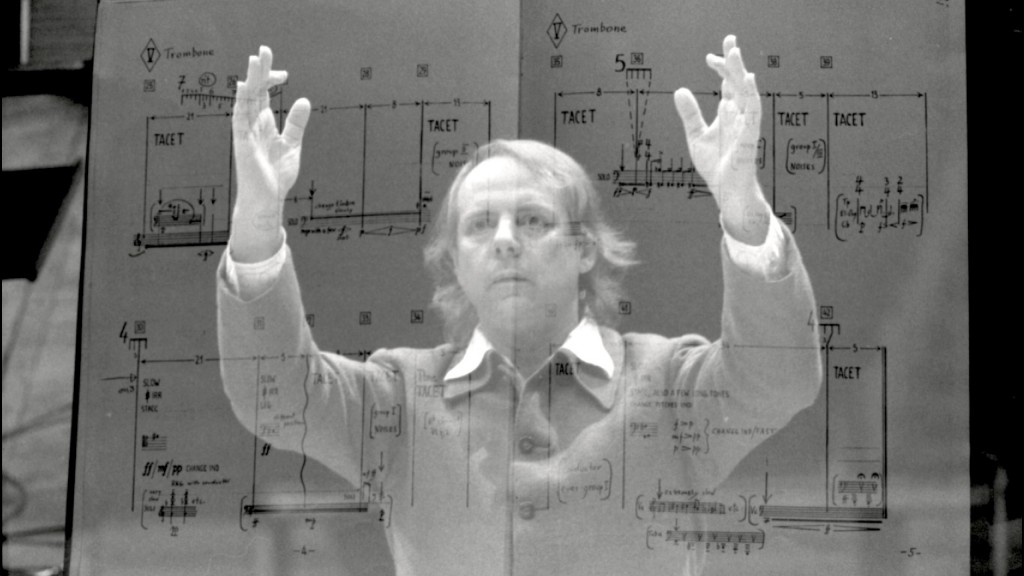

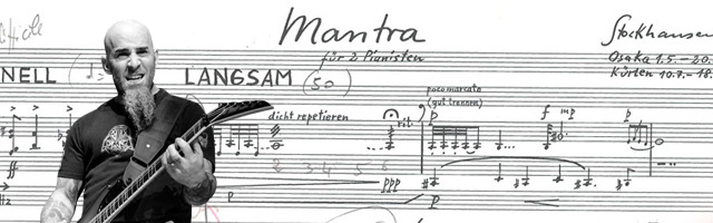

Last week I attended a performance of Stockhausen's Mantra in the Muziekgebouw aan 't IJ in Amsterdam. A piece in which two pianos (Pierre-Laurent Aimard and Tamara Stefanovich) engage in conversation. Cacophony for ears that are new to this music, but fascinating nonetheless. With listening to (classical) music one can get caught in what I shall call “an obsession with the right notes”. Are the notes - when they come to you in a not so familiair harmonic language - played correctly? Is there any kind of structure in this mayhem I'm hearing? A significant part of how you are going to appreciate (or not) a piece of music can depend on the (positive) answer to these questions because you don't want to feel cheated or lost. There can be a need for wanting to rely on the composer's integrity if the structure of a piece seems determined to hide itself. And that need can be most persistent. There is this video clip on YouTube. It shows Maurizio Pollini playing a piece for piano by Stockhausen. Pollini is counting. You see his jaw going up and down, like he is whispering. I have never seen him do that in Beethoven or Chopin. It's like the notes in Klavierstücke IX don't reveal their connection when he is playing them. He has to secure the relation between the notes by counting. To prevent that they will become islands. Entire of themselves. Pollini - Stockhausen - Klavierstück IX (Live 2002) (Click on photo to see clip) In the week before the Stockhausen concert I listened to lot of heavy metal. That same week trash metal legends Anthrax came to town and although this concert was played in my absence, the veterans of the mosh pit had my full attention. Madhouse, Indians, Caught In The Mosh and many more metal classics went high rotation in my living room. Music with the ability to burn down infinite unrest and generates new energy at the same time. It turned out to be the perfect preparation for the sound world of Mantra. With the energy of Anthrax in mind I went to my encounter with Stockhausen. And it's remarkable how heavy metal can open the gates through which modern classical music can enter. The gap between the musical world of Stockhausen's Mantra and the piano sonatas from Joseph Haydn is a bigger one than the gap between the former and a metal song. It's a bit like industrial noise in a unplugged session that is not completely unplugged. Nine Inch Nails, played on two pianos, percussion and a ring modulator - a device that synthesizes the notes from the piano into combination notes (thus turning harmonic sounds into enharmonic sounds). It added reverb on the piano that, unlike standard pedalling, didn't sound especially lush but gave it a touch of gamelan music. And at the fray ends of the sounds coming from the piano one could hear the fruits, both sour and sweet, of the industrial revolution. As if the music tried to came to terms with modern times. Tries to embrace what becomes, eventually, inevitable. During the 75 minutes of Mantra, there are a lot of things going on in which one can search, with futile efforts, for some points of reference. I, clean washed by the heavy metal therapy in the days prior, thinking more in sonic colors than in contrapuntal finesse, just let it happen. It's not that the mind, always looking for some kind of inner logic, isn't completely left to it but it took some time before the structure of the piece started to show glimpses of itself. It's as if the music is constructed with very specific ideas about sound in mind, more than it shows itself as the next logical step after Schönberg and the Second Vienna School. More like hip hop – with its samples based on colors of sound – than like traditional pop music – with its instruments tuned in a certain key. But as far as music theory goes, I have to admit that I lack expertise to back that comparison up. There is a bigger gap between Stockhausen's Mantra and a Haydn sonata than between the former and a metal song The dissonances in Stockhausen's music seem to revolt against the music that generations before him came up with. A bit like the power chords in heavy metal do. In both cases you can draw the same kind of energy from it. It's funny that looking for a stepping stone that would help me accept and appreciate the musical world of Karlheinz Stockhausen, I found help in the rock music of my youth first, before I looked for points of reference in 20-century composers like Pierre Boulez or György Ligeti (while I play Pli Selon Pli for entertainment purposes and I knew Pierre-Laurent Aimard already from a CD with piano music of Ligeti that I highly value). The dialogue between pianos in Mantra is not without humor. It even stretches that humor a bit by times – like a joke that it's told a few times too many. After one hour (around 1.03.25 in the video below) the music turns into some kind of Boogie Woogie-on-steroids that feels like a perpetuum mobile (be it only for a few minutes). It's the zenith of a piece of music that I receive with some proper back-and-forth movements of the head. Mantra from Karlheinz Stockhausen is caffeine for the brain that generates energy not unlike that of a rock concert. I say "Hell yeah!" to that.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed