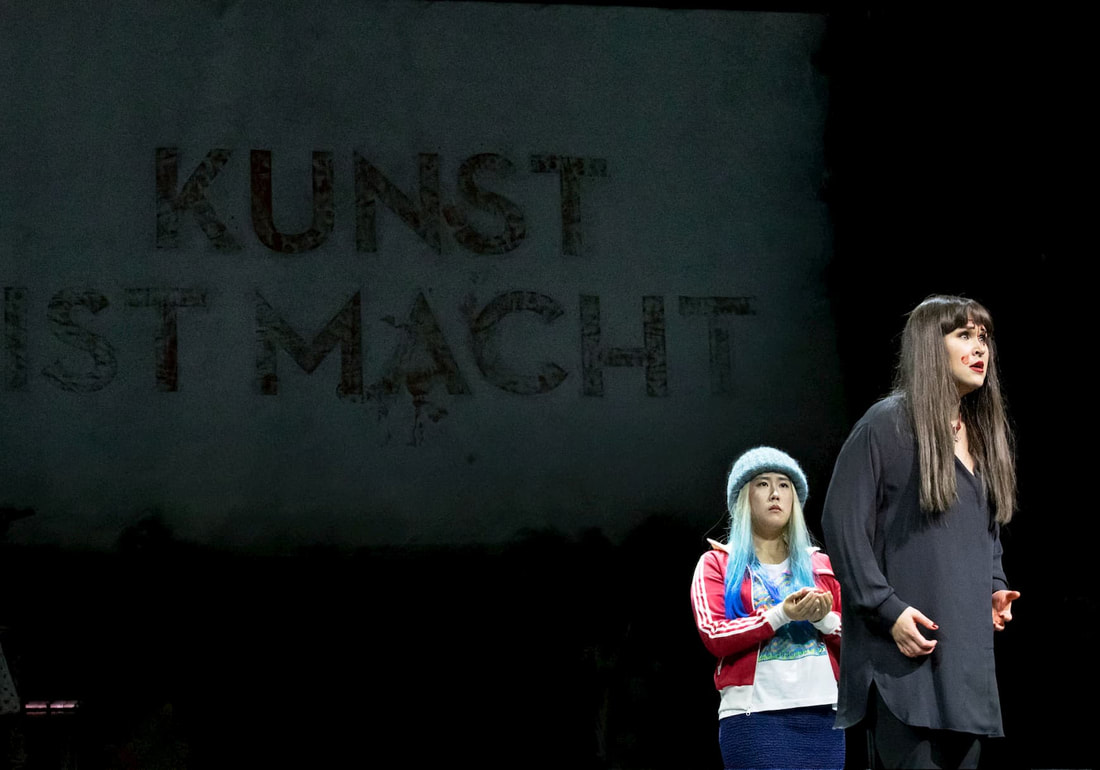

Opera Vlaanderen opens the new season with Milo Rau's production of Mozart's La Clemenza dit Tito. A performance in which Rau unleashes his "theater of reality" on Mozart's last opera, creating two performances in one. A performance of Mozart's opera on the one hand and that of the director's story on the other. A schizophrenic production that will undoubtedly split minds. Mozart composed La Clemenza di Tito just before his death, in a time frame of 3 months (there is even mention of 18 days, it was a rush job anyway) on the occasion of the coronation of Leopold II. The commission paid well, twice the amount one usually paid in Vienna for an opera, and that was not unwelcome for the composer in need of money. Because of that short time, no new libretto could be written so a libretto by Metastasio was adapted that was already half a century old at the time. Tito was an opera that served a political purpose and (therefore) was nailed in its time. Moreover, the form, the opera seria, was considered increasingly obsolete by the end of the 18th century. It may have been a more or less forgotten opera in Mozart's repertoire for a long time, but La Clemenza di Tito has since enjoyed popularity. For example, Tito's forgiveness inspired American theater producer Peter Sellars to create a production about coexisting in a modern society and, without attempts at updating, the opera appears to be able to stand on its own musical feet enough to justify concert performances. Milo Rau, theater maker and self-proclaimed revolutionary, ventures into his first opera with La Clemenza di Tito and begins its production with a kind of apology for it. An opera composed two years after the French Revolution in honor of a king. An opera that provides the nobility, the elite, with an areole of magnanimity. Rau has something to say about that. That is not only suspicious, that is morally reprehensible. That elite, the bourgeoisie, is only out to perpetuate its own power and maintain the status quo. It was so in the late 18th century and it is so now. The elite is disingenuous, its motives cannot be trusted. Tito's forgiveness is questioned by Rau. He turns the king into a man with narcissistic and neurotic traits, giving his texts ironic overtones and making them the words of an unreliable narrator. Rau turns Tito's court into an art gallery, a place where the king has his work applauded by his compliant entourage. That hip world is in sharp contrast to a refugee camp outside which is in a desolate state and where, as part of "law and order," people are being arrested. We witness an execution. All in the name of the king. Does the "merciful" Tito himself believe what he says? Rau deletes extensively in the recitatives of the original and cuts up the opera. After the overture, we move from court to refugee camp. We hear music from a ghetto blaster, a man (calling himself the last man from Antwerp) makes a speech about the city that has changed beyond recognition during his lifetime. His heart is cut out (literally). By then it has become unequivocally clear that Rau is not so much concerned with Mozart and his opera as with the story he himself has to tell. Mozart's Tito is merely instrumental to that story. A story about the elite imposing its will on the people and using art in the process to keep the people quiet. Art as opium for the people. "Kunst ist macht" we read on a video screen (why in German? I fear there is a, by now, worn-out reason behind it). Art, its capitalization, channels revolutionary thought, ensures that what is dreamed about does not become a reality. The king and his entourage are therefore artists or manifest themselves as such. Thus Tito is a painter and Vitellia presents herself as a kind of Marina Abramovich. All this under the nowadays inevitable presence of a cameraman on stage. (The last five operas I saw all had a cameraman onstage; is this current streaming-on-stage trend the first real theatrical legacy of the Covid period when (laptop) camera and screen proved indispensable tools if we wanted to see a performance and/or our fellow human beings?) Further, the question that arises here is: Are we, as audience in the theater, not both elite (bourgeoisie who benefit from the status quo) and common people (who see the arts as narcotic entertainment) at the same time? Rau illustrates the story of the opposition between elite and people, between man and his dreams, through clips of people who have sought refuge in Belgium. The performance thus squeezes two performances into one. Mozart's opera on the one hand and the director's story on the other. We see short biographical clips of singers that are a sort of behind-the-scenes footage while the performance continues onstage. We learn, for example, that Anna Goryachova (Sesto, here not a trouser role but 'just' a woman in a female role) is in real life a mother with child (with attendant worries). It creates Brechtian alienation, and a meta-effect, when she, as Sesto, gives evidence of her torned feelings toward Tito. Initially the two worlds of this performance, that of the director and that of Mozart's opera, have something to say to each other but gradually they let go of each other entirely. Then the story of the opera is no longer directed and we listen to beautiful arias that have then become a kind of soundtrack for documentary footage. The sincerity of those images about people telling about their personal history notwithstanding, they lose power toward the end - there is image inflation. One could almost see in it a plea for a concert performance; the music can stand perfectly well on its own when the director has apparently run out of ideas. As a theater production, this Tito definitely has its moments where Rau makes his point in a haunting way. As a staging of an opera, the result is somewhat poor. For that, the opera is too much of a vehicle rather than a grid to start from. It does not help that the story Rau wants to tell does not develop (it is fairly quickly clear what he wants to say) and that the texts projected on stage leave an increasingly pubescent impression towards the end. The elite, the bourgeoisie, is presented here as an undefined homogeneous bloc. Who are the Titos in today's world? What exactly does the desired radical change entail? It remains unclear. As a director in an opera house, the bastion of the establishment, Rau shows himself a bit like a teenager in a Che Guevara t-shirt. A young man who, in the safety of his room, abandons himself to romantic ideas of revolution. This production of La Clemenza di Tito deconstructs Mozart's opera and will undoubtedly split minds. But couple (stage) image to music and the music will prevail. Indeed, that music does its job and this Tito is carried by a fantastic cast and excellent musicians. Alejo Pérez gives lead to an inspired playing orchestra. Jeremy Ovenden plays and sings the role of Tito as Rau conceived it with conviction. The aforementioned Anna Goryachova excels, both in acting and singing, as Sesto. Anna Malesza-Kutny appropriately brings Vitellia to the brink of madness and Sarah Yang sings a very beautiful, sensitive Servillia. Of the "ordinary people" that Rau, following his own tradition, brings to the stage, the last man from Antwerp deserves a special mention. His biographical clip reveals that he holds no less than 70 different versions of Parsifal (and now, of course, we want to know which version is his favorite). © Annemie Augustijn Toward the end of the performance, a young man announces in a video his coming-out as bisexual, citing a city as a place where ideas have sex with each other. One could say, with that metaphor in mind, that this La Clemenza di Tito is a production in which Milo Rau courts Mozart but does not let it come to an intimate union. He goes his own way, eventually leaving Mozart to it. La Clemenza di Tito, Antwerp 10 September 2023 Perfromances: 10-Sept until 26-Oct (in Antwerp, Ghent & Luxembourg) Conductor: Alejo Pérez Regie: Milo Rau CAST Tito: Jeremy Ovenden Vitellia: Anna Malesza-Kutny Sesto: Anna Goryachova Annio: Maria Warenberg Servillia: Sarah Yang Publio: Eugene Richards III CHOIR & ORCHESTRA Koor Opera Ballet Vlaanderen Symfonisch Orkest Opera Ballet Vlaanderen - Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

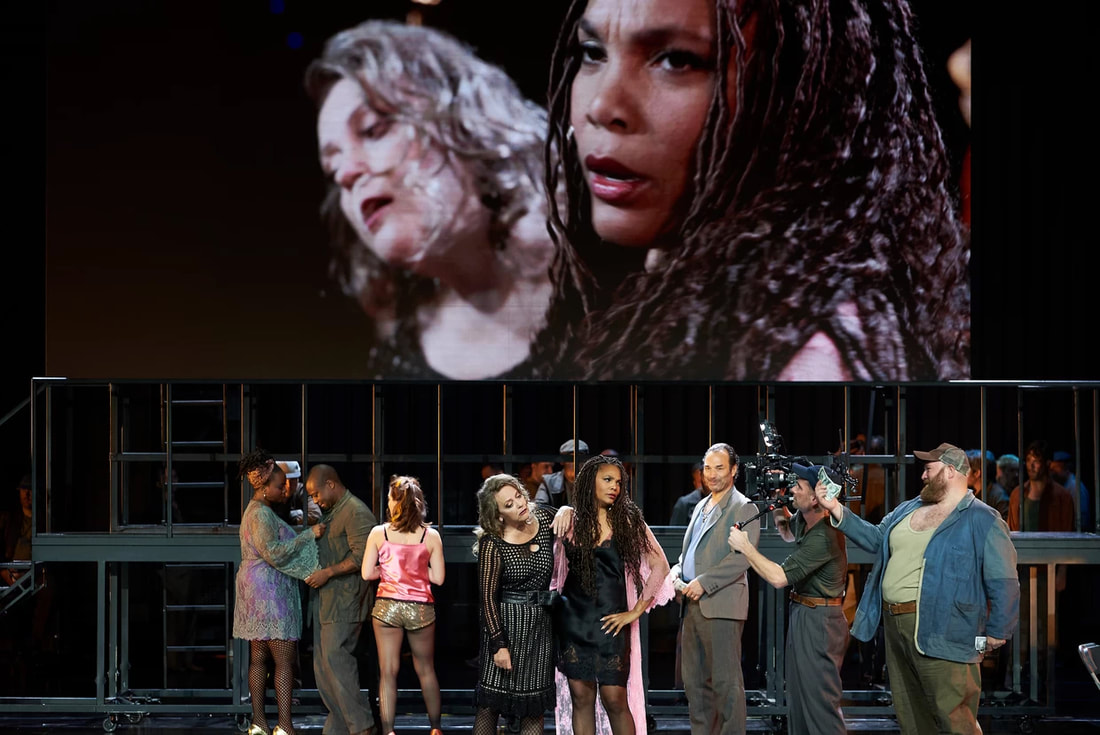

After his 2017 production of Salome, Ivo van Hove returns to The Dutch National Opera with Kurt Weill's "Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny. After his successful Salome (2017), Ivo van Hove returns to The Dutch National Opera with Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny. That return was postponed for three years because the originally planned performances of this production were cancelled in 2020 due to the Covid lockdown. Last year this production was seen at Opera Vlaanderen. Now The Dutch National Opera is opening the new 2023/2024 season with it. In the barren sands of Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht piece together a dystopian story in which man feasts on excess and gives in to primal urges. We see a stage with a large video screen. That's where it all happens. There we see how the city of Mahagonny is founded, becomes a place for all sorts of excesses and finally goes up in flames. Unlike previous opera productions by Van Hove, where the use of video images was often superfluous and gratuitous (Schreker's Der Schatzgräber for DNO!), the use of camera images, video projections and green screens in this production finds a justification within a set-up in which the stage becomes a place in which reality and illusion complement and challenge each other. A reality in which anything goes. A reality that is stripped of its illusions when not having money turns out to be punishable by death. The excesses of Mahagonny find a frenzied imagination in the excessive use of video. On a green screen, ultimum of the illusion in which man loses himself, someone is beaten to death in a boxing match, a line of men can be seen taking a prostitute from behind. These are images that leave little to the imagination, that alternately impress, depress and flatline. Images that, through their lavish use, emphasize the emptiness behind them but also make you wonder if the visual excess does not harm at some point. That the head, deliberately placed above the heart by Brecht, is not pushed away too much by the visual splendor that ultimately has a hypnotic and narcotic effect. The use of video on stage can now no longer be called new, although Van Hove still seems to be searching for the limits of its possibilities; the presence of a cameraman on stage is a fairly recent phenomenon. Social media have found its way to the theatrical stage and, since the Covid period, have hardly been absent. In the last five operas I saw, there was a cameraman walking around on stage whose recordings were projected onto a video screen. Reality recorded by cameras as an indispensable component of experienced reality. Mahagonny here gets an opera cast with an impressive track record. Evelyn Herlitzius, well-versed in Wagner and Strauss and Nikolai Schukoff (he previously sang the title role of Lohengrin at DNO) are, respectively, the con artist Leokadja Begbick and Jim Mahoney, the man who finds out that an empty wallet literally means the end. Herlitzius has never lacked expression; in addition to her singing, she has always had to depend to a not inconsiderable degree on her acting. In a role where acting is more important than the beauty of a voice, she is perfectly in place (I couldn't escape thinking of Elektra at her occasional outbursts). Nikolai Schukoff, together with Lauren Michelle's Jenny, forms a radiant centerpiece of a love that is, very opera-tesque, doomed. Lauren Michelle sings a beautiful role with which she poignantly colors her desires but at times its deeply human impact, along with the rest of the production, seems to fade into the digital oasis that is Mahagonny. That a production of a play that addresses the emptiness of excess sometimes gets itself caught up in the drive for technological splendor is not without irony. The story revolving around the seduction and perversion of ideals through greed for money finds a compelling performance with an excellent cast and fine orchestra. The Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Markus Stenz, a specialist in 20th-century repertoire, adeptly discharges its duty to bring Weill's musical world with elements of ragtime, jazz and tango to life with rhythmic alertness. Orchestra and singers, in connection with the dystopian story they tell, form a harmonious whole. The Chorus of Dutch National Opera effortlessly switches between a cappella and a quasi-Slave Chorus. They contribute, in no small way, in bringing Weill's musical world alive. In Mahagonny's predecessor Dreigroschenoper, it was said that the common man cannot care about morality until he has food (Erst kommt das Fressen, dann kommt die Moral). In Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, that adage is expanded into the motto of a city, a place where anything goes, provided it is paid for. "Erstens, vergeßt nicht, kommt das Fressen Zweitens kommt der Liebesakt. Drittens das Boxen nicht vergessen Viertens Saufen, laut Kontrakt. Vor allem aber achtet scharf Daß man hier alles dürfen darf.” The politically-satirical comments on capitalism continue to resonate especially today. With songs that have made it into pop music, the Alabama Song (The Doors) Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny along with its bristling and haunting music can be considered a unique amalgam of extremes. A musical theater that, in this production, is not so much a paragon of Brechtian alienation but rather characterized by an overwhelming of the senses. A production that reminds us with its exorbitant use of resources that it is often the simple gesture that leaves the deepest impression and to which the concluding oratorio-like chorus makes it known that for real drama, even when human degeneration reaches a nadir, real beauty is indispensable. Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (Kurt Weill & Bertolt Brecht), Muziektheater Amsterdam 9 September 2023 Conductor: Markus Stenz Regie: Ivo van Hove Decor & light: Jan Versweyveld Costums: An D’Huys Video: Tal Yarden Dramaturgie: Koen Tachelet Leokadja Begbick: Evelyn Herlitzius Fatty: Alan Oke Dreieinigkeitsmoses: Thomas Johannes Mayer Jenny Hill: Lauren Michelle Jim Mahoney: Nikolai Schukoff Jack O’Brien/Tobby Higgins: Iain Milne Bill: Martin Mkhize Joe: Mark Kurmanbayev* Sechs Mädchen von Mahagonny Viola Cheung, Thembinkosi Magagula, Elisa Soster, Raphaële Green, Kadi Jürgens, Jessica Stakenburg * Dutch National Opera Studio Chorus of the Dutch National Opera Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra Coproductie with Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, Metropolitan Opera, Opera Ballet Vlaanderen & Grand Théâtre de Luxembourg - Wouter de Moor

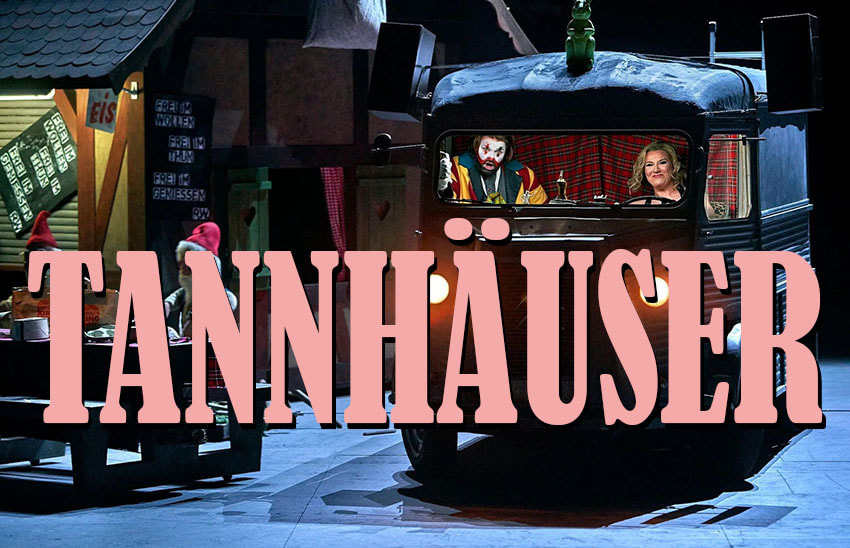

Bayreuth is over and I look back, satisfied and somewhat nostalgic (you never know when you'll be back). What the two productions I've seen (Parsifal and Tannhäuser) have made abundantly clear is that nothing compares to the thrill of a live performance. There was some playing around with Augmented Reality in Parsifal. That means, for the limited part of the audience that had access to AR glasses. The result, according to the reviews I've read about it, didn't add anything essential to an otherwise conventional production. The graphics resembled a video game from 10 years ago. Everything was moving and there was a spear coming at you. It sounds a bit like those first 3D movies where everything was thrown at the screen (the viewer). As if to emphasize the novelty, not to support a story. Tannhäuser in a production by Tobias Kratzer is proof that the use of (relatively) new media (such as video) and the bringing together of pop culture and classical repertoire can happen in a completely natural way with amazing results. It was a textbook example that ideas carry a production, not technology. Click on the thumbnails below to read more about it. - Wouter de Moor

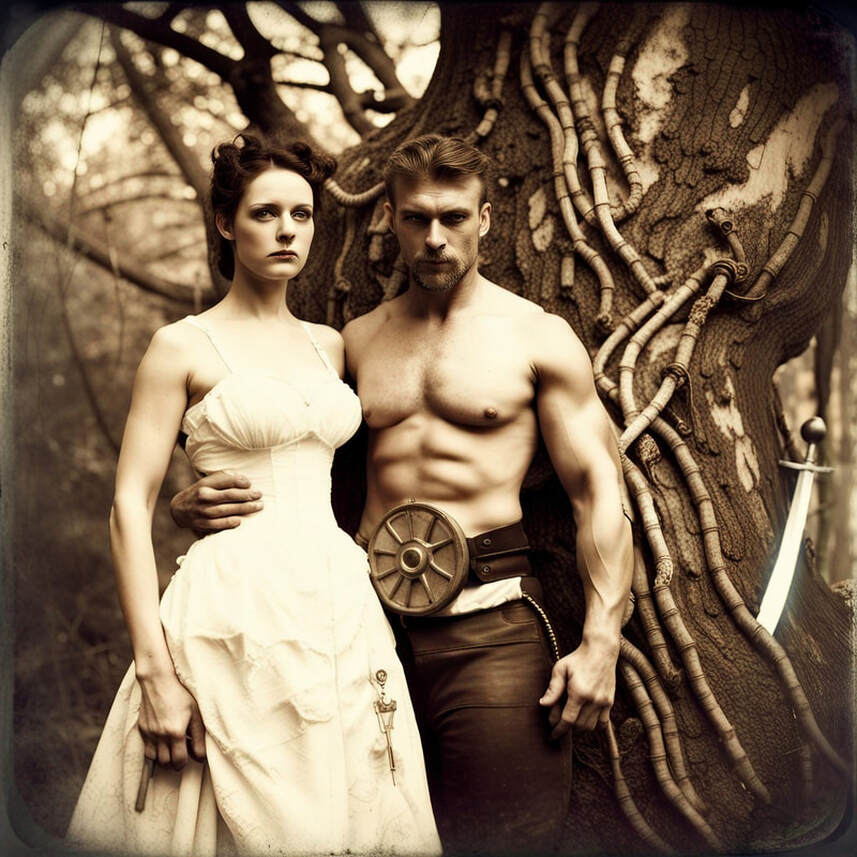

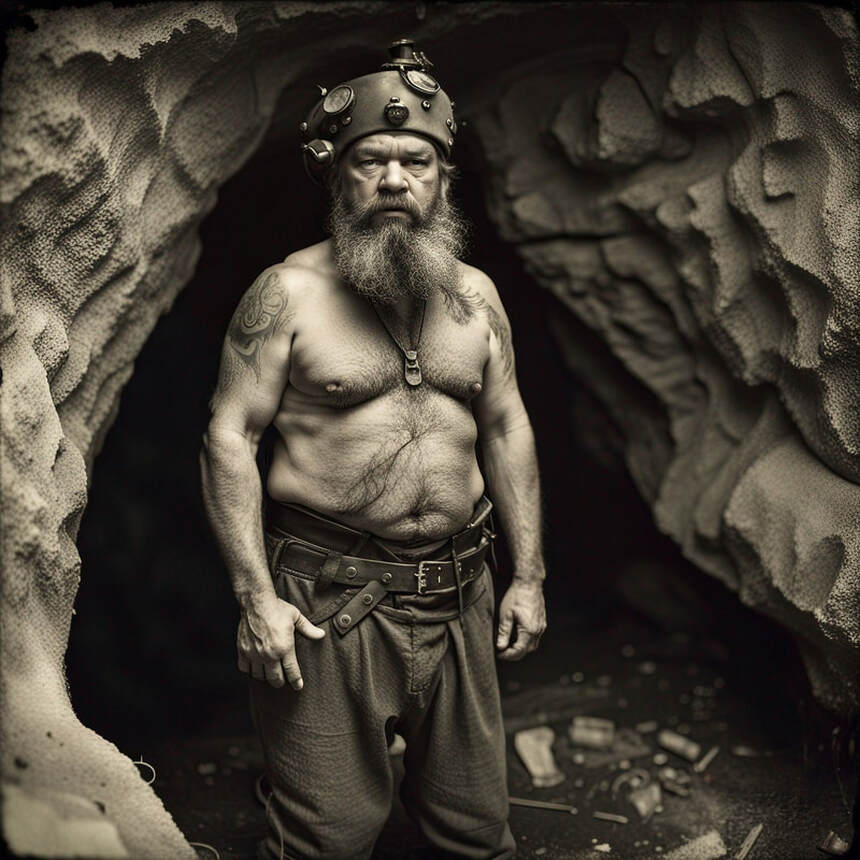

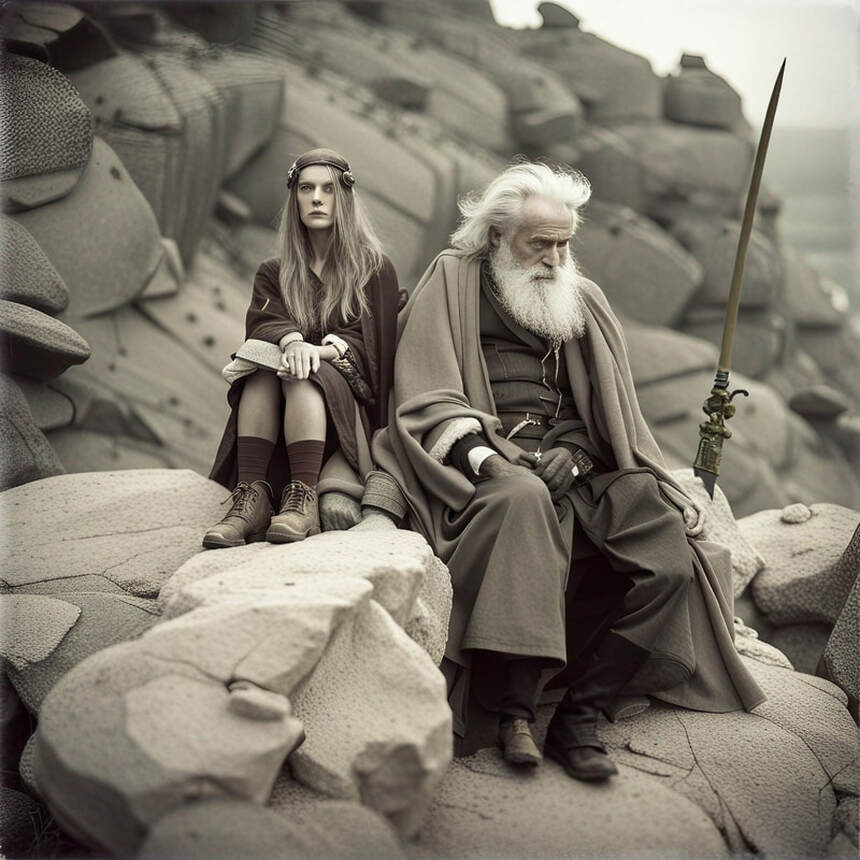

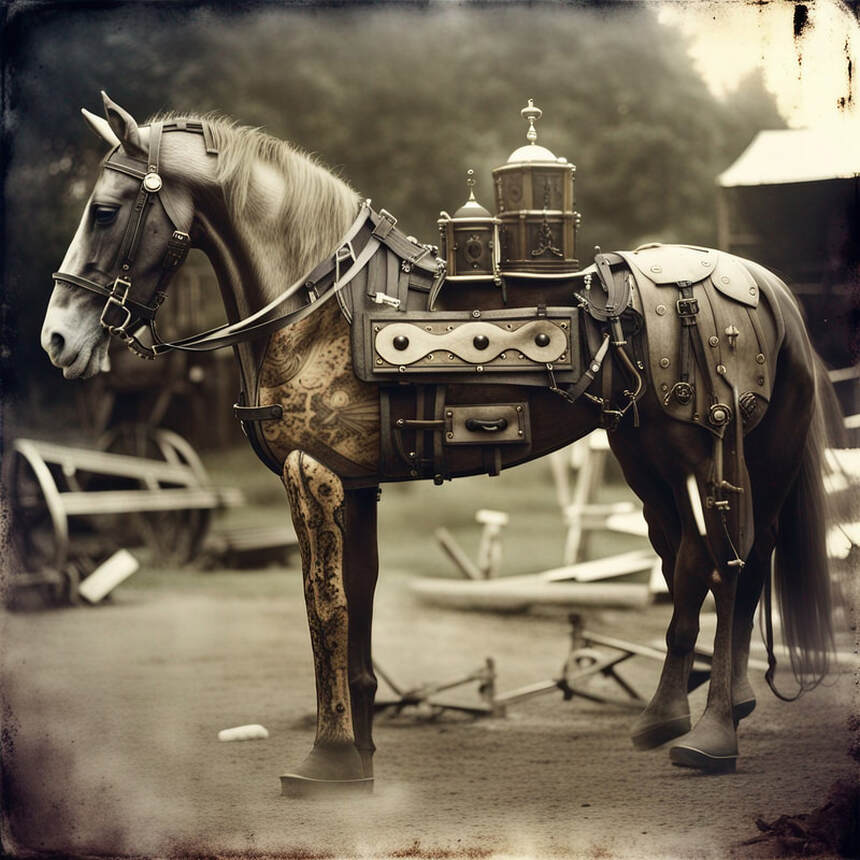

A tale in images of Der Ring des Nibelungen for which inspiration was sought in Steampunk - that combination of nature and digitless science in a world that can be simultaneously antique and futuristic. The images were generated with AI software.

The world of the story of Der Ring is a world in which humans, the moment the waters of the Rhine begin to flow (to the tones of a swelling Es chord), have already left their mark. A world in which industrialisation and moral ambiguity go hand in hand (a bit like in the Bayreuther Chéreau Ring). A world in which a desolate landscape is host to gods, giants, dwarves and humans who all seem, in one way or another, to be lost in it. A landscape in which creatures are strangers to the world they inhabit, strangers to each other, and above all, strangers to themselves.

DAS RHEINGOLD (the preliminary evening of the Steampunk Ring) First scene Child of a loveless mother and ugly as hell. Yet, Alberich the Nibelung hopes for romance when, walking along the banks of the Rhine, he hears the singing of three Rhinemaidens. The teasing lasted a bit long. It became clear to the Nibelung that the three water nymphs made fun of him and never considered him a serious partner for their love. Fortunately, they were kind enough to point out to Alberich the Rhinegold and the secret it held: the gold can be made into a magic ring which gives power to rule the world, if its bearer first renounces love. The dwarf does not think twice. He, who has never known love, now knows that he will never need love. Alberich steals the gold, and flees. Second scene We leave the lowlands and find ourselves in a mountainous landscape where chief god Wotan casts a satisfied glance at the Valhalla that Fasolt and Fafner have built for him. It appeases, for now, Wotan's appetite for megalomania. As payment for their services, the giants have already taken Freia. For Fasolt, a giant with a sensitive heart, Freia is more than a deposit. For him, she is the promise of something beautiful in his life. But no Freia, no apples, no eternal youth for the gods. Wotan dismisses any concerns his fellow gods may have about this. Loge surely will come up with a solution for this. Chain-smoking cunning Loge is certainly not without humour. You are never sure what to make of him but if you are susceptible to it you will certainly laugh at his dry remarks. He talks about Alberich, his golden ring and how the dwarf subjugated his fellow Nibelungen to mine treasures for him. Loge suggests the giants to pay them with the Nibelungen hoard. The giants agree, for now. To the sound of a droning, dark orchestral interlude, two ominous-looking fellows descend into Nibelheim. One of them, Wotan, can think of only one thing, the ring and the power it holds. Loge and he are not here for business as usual. Their business is theft. Third scene In Nibelheim the Nibelungen are enslaved by Alberich with the power of the ring. Alberich's brother, Mime forged a magic helmet, the Tarnhelm. With this device one can become invisible and take any shape one want. Fourth scene Alberich should have known better when Loge dared him to use the Tarnhelm to take the form of a toad. But the dwarf refused to turn down the challenge and now faces the consequences. Loge and Wotan capture the toad and rob him of the ring, the hoard and even the Tarnhelm. Alberich, who once cursed love, now curses the ring - thus condemning all its possessors. Once back in the godlike realm, Wotan cannot enjoy the ring for long. The giants won't settle for just the Nibelungen hoard. They want that ring too. Once in possession of it, Fafner, in lust for the ring, beats his brother Fasolt to death. Cain and Abel in the world of the gods. Wotan sees it happen with a certain sense of discomfort. On his way to Valhalla, across a rainbow bridge Donner smashed out of the rocks, the nuisance in him grows. He has been given a preview of the curse the ring carries. Not that Wotan was not warned about all this. Erda, the Goddess of the Earth, had addressed the chief god in lyrical yet insistent terms, warning him of the misfortune the ring would bring him. So Wotan gave the ring to the giants, but even more than by her words of warning, he was impressed by Erda's seductive innocent appearance. And as soon as this opera, Das Rheingold, is finished he will impregnate her with eight children: the Valkyries. Those children, Brünnhilde in particular, we will encounter in the following opera. They had one job. And they miserably failed at it. Now, at the end of Das Rheingold, the daughters of the Rhine lament in horror over the loss of the gold they were supposed to be guarding. We leave them alone for now but they will return in the last opera of this tetralogy: Götterdämmerung. But more on that later. Next: Die Walküre. Software: StableDiffusion XL, Photoshop

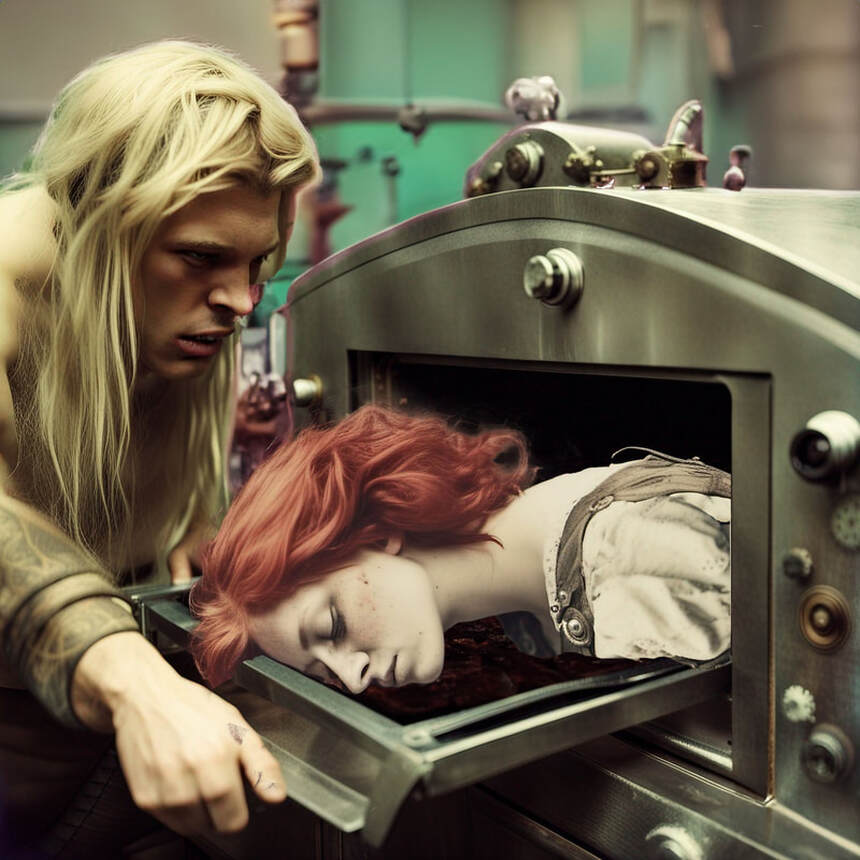

- Wouter de Moor A tale in images of Der Ring des Nibelungen for which inspiration was sought in Steampunk. The images were generated with AI software. After Das Rheingold, Wotan not only fathered eight children with Erda, the Valkyries, but he also fathered the Walsungen twins Siegmund and Sieglinde. Wotan also had time between operas to stick a sword in a tree, Notung. A weapon for times of need, for him who deserves it. First act She found him after a violent storm in the house. It took her a while to recognise in the stranger her long lost brother, the love of her life. After everything Sieglinde had to endure, she no longer dared to hope for a little bit of happiness in her life. The man she was forced to marry, Hunding, was not the most sensitive of characters. That is not to say he was a man without honour. That stranger who seemed to have a kinship with his wife could stay a night but the next day he would be food for the dogs. Second act Hojotoho! For Brünnhilde, life is a tremendous exciting affair. And soon she is going to assist Siegmund, the one and only true hero of this whole story, in his fight with Hunding. Life is coughing up roses. Fricka turned a blind eye to it for a while, Wotan's cheating. But now enough is enough. Wotan must withdraw his support for Siegmund and support Hunding. A marriage must be honoured. And if Wotan has any love for power, he will make sure that he himself abides by the rules he imposes on everyone else. She comes in hard on him, on her husband the chief god. With cool headed arguments she shatters Wotan's illusions of freedom and love. Both old-fashioned and ahead of her time she is: Fricka, the old storm, the old party pooper. Third act It is one of the most recognisable tunes in music history. The sonic storm on which the Valkyries bring dead heroes to Valhalla on their steam-powered horses. The Walkürenritt is exactly the boost this opera needs after the dramatic second act (in which Siegmund is killed by Wotan's intervention, Wotan has angrily gone after Brünnhilde and Sieglinde has fled into the forest with the fragments of Notung). All the drama that has preceded finds a climax in Wotan's moving farewell to his daughter Brünnhilde, which may be considered one of the most beautiful moments in all of opera. For her who was once his favourite daughter, Wotan had in mind an honourless sleep, in a stove in an old factory far away. Eventually, his anger soothed and he summoned Loge, who was after all the God of Fire, to light the stove. Only the bravest hero will dare to risk his hands on the furnace fire that now protects Brunnhilde. We meet that hero in the next opera: Siegfried. Wotan's Farewell (bonus reel)

Audio: George London (Leinsdorf, 1961) Software: StableDiffusion XL, Photoshop, After Effects

- Wouter de Moor A tale in images of Der Ring des Nibelungen for which inspiration was sought in Steampunk. The images were generated with AI software. While Brünnhilde was sleeping, Sieglinde, whom she rescued, gave birth to a child. That childbirth Sieglinde did not survive. Ignorant of his parentage, her son, Siegfried, has grown up with the dwarf Mime. First act Mime is a clever dude. Good with tools too. But with forging Notung's shards together, he struggles. For the difficult tasks, however, he has Siegfried, the archetypal strong boy, whom he intends to use to eventually get the ring and the treasure of the Nibelungen, Young Siegfried is a man whose strength is matched only by his foolhardiness. The latter is, to be clear, a virtue. It perhaps requires some mental flexibility to go along with the idea Wagner apparently had of a hero. That he has Siegmund (perhaps the only one in this entire history worthy of the qualification hero) followed in the story by the gullible Siegfried, but in this opera cycle it happens. And who are we to second-guess the master here. Second act After killing his brother, Fafner retreated to the forest where, with the help of the Tarnhelm, he transformed himself into a dragon train. Loaded with the Nibelungen hoard, he rampages through the dark depths of the forest. And no one dares to come close. Did no one dare to approach Fafner? No, there was one person who dared to face Fafner without fear. Siegfried, the brat who did not even know what fear was (and therefore could not be brave) smashes the dragon locomotive to pieces with Notung. After that act of demolition a Waldvogel pops up. Besides telling Siegfried about the existence of Brünnhilde, she tells the pure fool about the ring that is there among all those treasures. Why does the Waldvogel do that? Has that creature of the woods been sleeping the previous operas or something? As we saw at the beginning (after Wotan mutilated the world ash tree) nature is corrupted - and those who represent nature not to be trusted. Purified by dragon steam, Siegfried can also read Mime's mind now. He kills the dwarf on his way out. Third act They are like a tired old couple. He's too tired and disappointed to be mad at her. And she, despite being the Goddes of the Earth, doesn't know what to say to him anymore. After his farewell to Brunnhilde, Wotan is no longer himself. As Wanderer he still wanders through this opera, but the end he's been longing for since the second act of Die Walküre can't come soon enough for him. When Siegfried crosses Wotan's/Wanderer's path, an important part of the latter's wish for the end is about to be fulfilled. When Siegfried recognizes in Wotan the man who had a hand in the death of his father Siegmund, he shows, for the first time, some emotion. He smashes the spear of the chief god into pieces, after which Wotan calls it quits. From then on Wotan's presence in this story is reduced to the presence of his two ravens, Huginn and Muninn. Siegfried continues on his way and arrives at the old factory that the Waldvogel told about. He smashes a door and enters the factory hall. There is an oven at the back against a high wall. Blazing with flames. He goes looking for a pair of asbestos gloves. The dragon could not frighten him, but now that Siegfried sees a woman for the first time, he is shocked. What to do in such a case? Kiss her awake, like in fairy tales? Allright then. While Brunnhilde, upon waking up, mistakes the lamps in the factory hall for the sun, Siegfried is already preparing for the final duet. They are a lovely couple, Brünnhilde and Siegfried, the aunt and her cousin. In a frenzied, passionate, insane duet, they scream each other from one climax to the next. Love and death, death and love. And laughing of course. Afterwards they fall into each other's arms. As we saw with Siegmund and Sieglinde, also Siegfried and Brünnhilde like to keep it in the family when it comes to love. And while the new love couple snuggles together, we prepare for the final: Götterdämmerung. Software: StableDiffusion XL, Leonardo, Photoshop

- Wouter de Moor A tale in images of Der Ring des Nibelungen for which inspiration was sought in Steampunk. The images were generated with AI software. After the opera that bears his name, Siegfried takes some quality time with Brünnhilde. He now has a life he did not know before. Not that he has now become a proper family man. He is still a rascal, some tableware occasionally breaks, but he leads, especially for a hero who killed a dragon, a relatively quiet life. Prologue Weaving the Rope of Destiny, the Norns read of the past, the present and the future. No good news for the gods coming up. As their narration approaches the point where the fate of the ring becomes clear the rope breaks. Well, we will see for ourselves in due time. Not that he didn't want to break it to Brunnhilde sooner but now he really needs to go. In search of new adventures. After all, Siegfried is the hero of this story and too much domestic happiness knocks the story dead. After kissing her goodbye he gets into his zeppelin, on his journey he sees the Rhine below. First act Siegfried is on his way to the world of the Gibichungen, the humans in this story. And with the arrival of humans on the scene, things take another dramatic and decisive turn. But first Siegfried is welcomed in a beautiful hall (for those who have a taste for it) by Gunther, king of the Gibichungen people. Gunther needs to get a woman. A woman worthy of a king and Hagen, son of Alberich, has come up with a cunning plan for that. Brünnhilde is the perfect bride for Gunther and to make that happen Siegfried is going to help him. Siegfried himself doesn't know that, as he doesn't know anything anymore after Hagen pours him a cup of tea. What Siegfried does know is that he is going to court the woman sitting there at the bar (her name is Gutrune) While Siegfried is offered a cup of tea on the other side of the banks of the Rhine, Brünnhilde is also having tea. Waltraute, sister in Valkyrie affairs, is visiting but things don't really want to get cosy. She won't give away that ring she got from Siegfried, even when Waltraute kindly but urgently asks her to. (Neither would you if you were asked to give away your wedding ring.) But nastier matters await Brünnhilde. Siegfried, with no active memory of her, has fallen for Hagen's trick and is on his way to Brünnhilde to win her for Gunther. With the help of the Tarnhelm, he takes the guise of Gunther, himself too weak to make a sturdy woman like Brunnhilde his own, and takes Brünnhilde back to the Gibichungen court. Second act Brunnhilde does not exactly react relaxed when she finds out that Siegfried has cheated on her with another woman. She seeks revenge. And in the same way that Siegfried let himself be used by Hagen previously, Brünnhilde lets herself be used by Hagen. She engages in a plot to kill Siegfried. Third act Siegfried is always a cheerful guy but today he is extra cheerful. Today he goes hunting with Hagen and his men. But first he is going to tease some Rhinemaidens who are interested in that ring of his. Shall he give it back? (Perhaps/perhaps not.) Siegfried's death

(ominous music playing) After the dramatic events during the hunting party in the forest where Hagen kills Siegfried, we are heading towards the finale of Götterdämmerung and the end of the entire Ring cycle. When Brünnhilde finds out that it was Wotan who was behind it all, has tricked her, she is in a blaze. The gods need to go and with them mostly everything and everyone else. Even her favourite horse Grane, a loyal companion in good times and bad, does not escape her destructive drift. The world needs to be cleansed and everyone needs to do their part. A woman setting the world on fire. Brunnhilde has never been a pussy but the injustice done to her fuels her anger with a deeply felt determination. With Valhalla going up in flames, the world as we know it comes to an end. An end that harbours a new beginning. The beginning of a world without gods. Go and rest Wotan, your time is (finally) up. The Rhine overflows its banks, extinguishes the flames and the Rhinemaidens swim in to claim the ring. The Rhinegold is back where it belongs, at the bottom of the Rhine, where we can only hope the daughters of the Rhine will do a better job of guarding it this time. Epilogue (bis) We leave it here with the man who set all of the preceding drama in motion. What has become of Alberich? The story goes that, after the Rhine overflew its banks, he found shelter in an abandoned mine. Thus surviving, as the only one of the main characters, the story of Der Ring des Nibelungen. A story that is, after all, named after him. Stories circulate of people having seen Alberich years after the world of the gods had come to an end. The dwarf is said to lead a reclusive life and rarely go out. Waiting for time to come and get him too. But if you do happen to see him, perhaps you should ask him about it, about the story of the ring. Maybe it will teach you something. About yourself. About the world you live in - a world without gods. Software: StableDiffusion XL, Photoshop, After Effects

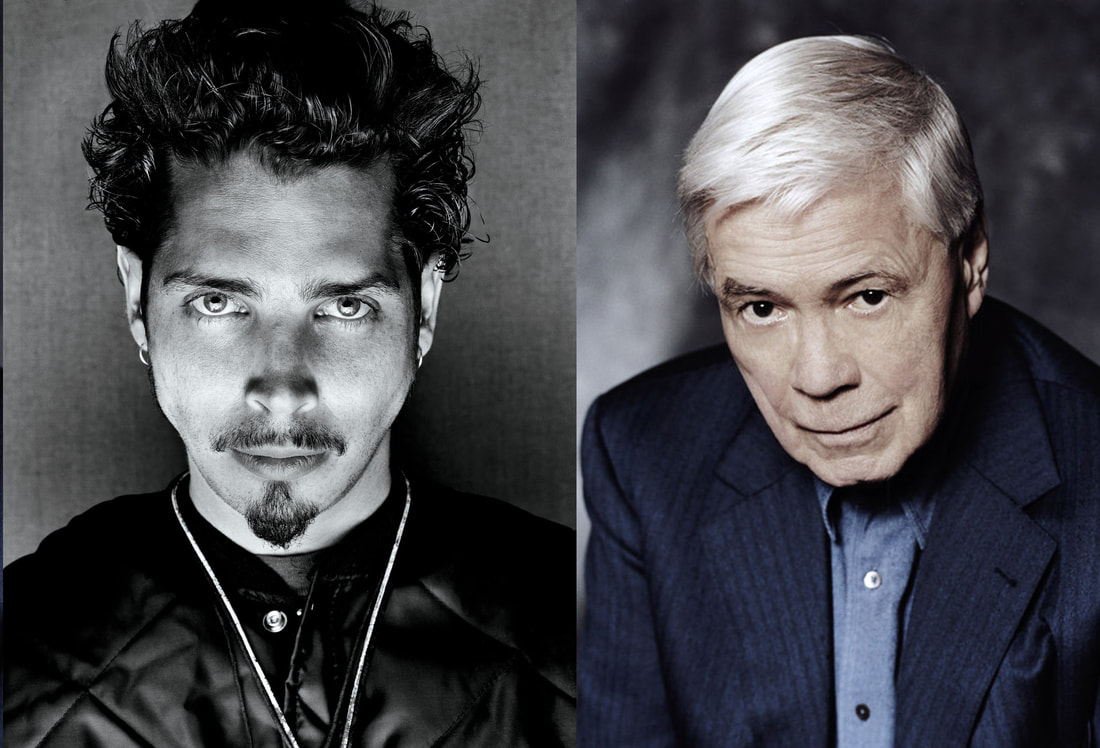

- Wouter de Moor Gustav Mahler, Chris Cornell and Helmut Berger died on 18 May. That day is a bit the day of the dead. On 18 May 2023, Helmut Berger died. Perhaps his best performance was the title role in Visconti's Ludwig II, in which Berger gave a gripping portrait of the Märchenkönig: the king of Bavaria, maecenas of Richard Wagner, without whom there would have been no Ring des Nibelungen and no Festspielhaus in Bayreuth (see also this article). Helmut Berger is only one of many who died on 18 May. The day links the deaths of Gustav Mahler, Chris Cornell and others but we'll start with a birthday ... On 18 May 1883, Walter Gropius was born. On 18 May 1911, on Gropius' 28th birthday, the man with whose wife he had an affair with died. Gustav Mahler knew about Alma's affair with Gropius and his dismay at it he scribbled down in the margin of the score of his 10th symphony. Almschi! Für dich zu leben! Für dich zu sterben! Written with death in prospect and a wife who was unfaithful to him. The composer/conductor's mind was one that was in an overheated state in the last stage of his life. On his deathbed, Mahler had asked for a jar of ants to be placed next to the bed. The swarming of the little critters was supposed to distract his mind from the agony his body was going through. In founding Bauhaus, Walter Gropius wanted to pull architecture out of the realm of art so that it would focus on functional and accessible designs. You could call him the spiritual father of IKEA. More threads of destiny converge on 18 May. On that day in 1980, Ian Curtis hanged himself. Just before Joy Division was to leave for America for a tour and just before the band was to release its second album. The last film Curtis (you don't have to wait for death to tear us apart, love already does) watched was Werner Herzog's Stroszek. A film that premiered almost on 18 May (on 20 May 1977). Life apparently is extra hard on 18 May because on that day in 2017, Chris Cornell was found dead in a hotel room in Baltimore. He had just finished a gig with his band Soundgarden (their best record Badmotorfinger is a badass beneficial massage for eardrums and soul). It was at Gustav Mahler's special request that, after they would have determined death, they would stab him in the heart with a pen to prevent him from being buried alive. Being buried alive, a primal fear, especially in the pre-intensive care era, is a subject central to many a horror story and at least one song cycle. Lebendig Begraben is a song cycle written by Swiss composer Othmar Schoeck based on 14 poems by Gottfried Keller. The cycle depicts the thoughts of a man who is mistakenly buried alive after falling into a coma and being declared dead. And Dieter Fischer Dieskau, the legendary German Lieder Singer who died on 18 May 2012, gives one of his most impressive performances here (see clip in link). - Wouter de Moor

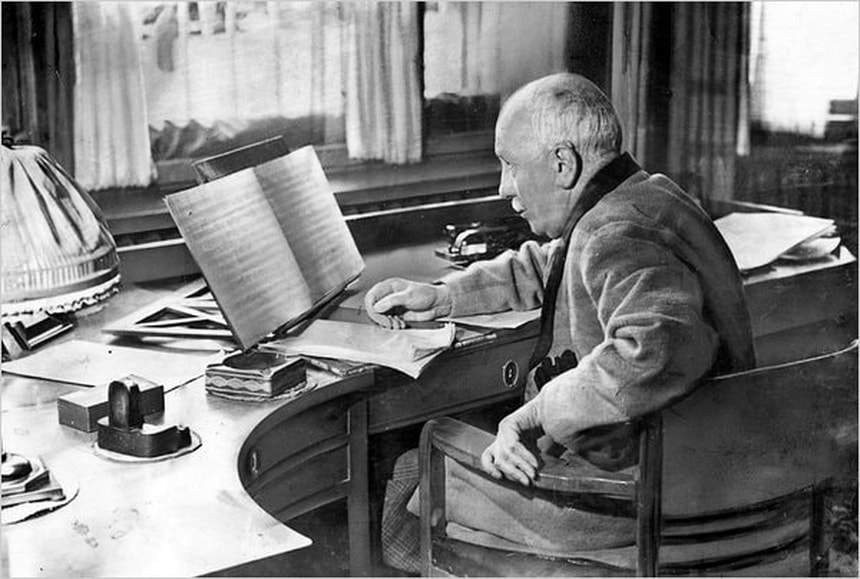

To commemorate the bombing of Rotterdam (on 14 May 1940), the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra is touring a number of places in the Netherlands with Gustav Mahler's 2nd symphony, visiting Amsterdam on 16 May, two days before Mahler's death anniversary. The city where Mahler himself conducted the Dutch premiere of this symphony in 1904. According to Stefan Zweig, art can make palpable what is crushed between the millstones of history. With the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra's performance, conducted by Lahav Shani, of Mahler's mighty second symphony, art seemed to aim to make sense of both the millstone and the crumbs. In a very confident reading, Shani led the Rotterdam orchestra along a journey of extreme moods: a traverse through deep valleys and euphoric heights. In what is perhaps the most operatic symphony in the repertoire, Shani opted for relatively slow tempi for the theatre of the second symphony (this was not a performance that would fit on one CD). Tempi with which he electrified moments and maximised expectations and which showed great insight into the architecture of the piece. On rare occasions, such as towards the end of the first movement, the slow tempi seemed to stall the journey, seemed to rob the music of its forward moving power, but that comment may be taken as splitting hairs in the context of this majestic performance. Mahler's Second is a symphony with strong contrasts between the movements, and in a good performance these contrasts complement each other, recognise in each other's differentness a kindred spirit. Mahler originally wrote a programme for his symphony but later omitted it. Within the context of this performance, the commemoration of the destruction of a city, and this symphony's nickname, Resurrection, music as ultra-powerful to the imagination as this one does not need a programme anyway. Little can match the hallucinatory powers of the brain as it searches for the personal images and feelings that the cathedral sounds of the Mahlerian orchestra evoke in it. At the crossroads where music and listener meet, a theatre of the mind is erected that no programme can do justice to. Despite the vast resources deployed, a large orchestra plus choir and solo singers, it is art that ultimately reveals itself to the listener in an extremely personal and intimate way. In Mahler's ingenious orchestration, in the details of the instrumental parts, the symphony is like a landscape in which the story of a life unfolds. Inseparable from life is death - the knowledge that time is limited is omnipresent in Mahler - and in his Second Symphony, Mahler sets himself nothing less than the goal of conquering death. The thundering percussion and raging strings created an irresistibly demonic atmosphere, with melodies cutting through the air like razor-sharp riffs. It was like a desperate opera of redemption. With those ambitions and pretensions in mind, it can be called remarkable that the text and music Mahler deploys speak to the listener in such a poignant way. Grand gestures that connect with intimate feelings, we love it at Wagner & Heavy Metal where we don't shy away from that irresistible mix of bombast and vulnerability. The form determines the content, the lyrics in the last two movements are a kind of religious tearjerker, but by piling up what would be clichés in the hands of lesser composers, Mahler, without falling into flat sentiment, rigs up an edifice that inspires awe and moves profoundly. It is up to performers to do justice to that brew of contradictions in a non-conflicting way, to leave nothing underexposed. The Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra and its conductor masterfully fulfilled that task. Everything fell exactly into place. Everything remained defined and audible. An orchestra that does not have its home base in the Concertgebouw might fall into the trap of playing too loud and muddle the sound. But none of that. Nothing was lost, from the softest passages to the fiercest eruptions of sound, the orchestral sound, even in the most forceful moments, remained transparent. The thundering percussion and raging strings created an irresistibly demonic atmosphere, with melodies cutting through the air like razor-sharp riffs. It was like a desperate opera of redemption, in which the composer and performers took us from the deepest caverns of the underworld to the inescapable climax where a divine, heavenly army resounded. That last movement, where orchestra and the fantastic Laurens Symphonic Choir forced the listener to awe and humility, was the perfect summation of all that had preceded it. One could only bow one's head in undergoing the passionately expressed desire to overcome what is inevitable for mere mortals, death. Grateful to have been present at a performance as lofty and majestic as this one. A performance in which you experienced music you know well (or think you know well) as if for the first time. And in essence, it was. The orchestra and conductor were improbably good, always in full control of the big lines and details in Mahler's tapestry of sound, so that what was unleashed on listening ears created the impression as if it could not have been done any other way. Thus, on the occasion of the commemoration of the bombing of Rotterdam, Mahler returned to the place where, since Willem Mengelberg started canonising his symphonies over a hundred years ago, he has never left (see box). And we are not done with him yet. Performances like this show time and again that there is little in the symphonic repertoire that can be compared with or stand up to the Austrian sound poet. It seems only inevitable that in the future, Mahler will continue to find new audiences. Willem Mengelsberg's role in music history is a story in itself. From a champion of Mahler's music (he called Mahler the Beethoven of our time) to a persona non grata who was kicked out of the country for being too close to the Germans during the occupation of the Netherlands.

During the German invasion of the Netherlands, and the bombing of Rotterdam, Willem Mengelberg, despite the threat of war, stayed in Germany where, in July 1940, he gave an unfortunate interview, to put it mildly, in which he seemed to approve, or at least downplay, the German occupation of the Netherlands. He is even said to have raised a glass to the Dutch capitulation there. From then on, Mengelberg would be seen as a country traitor and the Dutch would not forgive him his friendly dealings with the Nazis (he even accepted a Nazi ban on Mahler's work). Whereas German colleagues (such as Karajan & Furtwangler) could return to work after the war, after a process of denazification, all that remained for Mengelberg was a professional ban and exile. He would die in his Swiss chalet, Casa Mengelberg, on 22 May 1951 - on the 40th anniversary of Gustav Mahler's funeral. Mahler - Symfony nr. 2 in c 'Auferstehung', Concertgebouw Amsterdam 16 May 2023 Lahav Shani conductor Rotterdams Philharmonisch Orkest Laurens Symfonisch Chen Reiss soprano Anna Larsson mezzo-soprano - Wouter de Moor

Whether reflecting on the past in "Der Rosenkavalier", acknowledging the transitory nature of life in the career and music of Metallica, or the cycle of rise and fall in Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen, time is a central theme that reminds us that everything changes and passes.

The, on paper pretty bland story, turned out to be provided with sublime musical commentary by Strauss - full of irony, sarcasm and drama. Moreover, an engaging opera experience could do just fine without dystopian, murderous family relationships. There was life after Elektra, it turned out. And, suprise, the humorous moments turned out to be really funny. The action was perfectly tailored to the text and music. It turned the world of a pseudo-wig time that Strauss and Hofmanstahl had constructed into an electrifying universe. I needed a production like this to convert me to Der Rosenkavalier. Now, in revisiting this production by the Dutch National Opera, 8 years later, the machine of Personenregie appears to be less tightly tuned. Moments where I noted a smile 8 years ago, including the moment when Ochs is stabbed in the leg by Octavian, now go unnoticed. There is, of course, no substitute for the thrill that comes with the power of a discovery, and it’s logical that looking at the same production a second time, happens with a different, more seasoned, pair of eyes. But the regie lacks the finesse that made the earlier incarnation of this production so irresistible. Where the first time I made a triumphant Marx Brothers comparison (A Night At The Opera), this time, instead of humour, melancholy lingered the most. The wistfulness and wisdom of the Marschallin and the descending melody line that provides the sparkling love between Sophie and Octavian with a warning, an afterthought. Lost illusions of love lie ahead, the music seems to want to tell us. The trio at the end is one of heavenly beauty (it was played at Strauss' funeral in 1949). It is extra beautiful because that first gradually ascending melody in which the voices of Marschallin, Octavian and Sophie coincide is not repeated. At most, it is referred to, as much in Der Rosenkavalier's tapestry of sound is a web of references in which the repetition is never just the repetition. In a piece of music where repetition is used most successfully and effectively, repetition is never just the repetition. Our great friend Richard Wagner knew that. His leitmotifs are melodies and themes that recur, but the motifs that sound the same are slightly different each time due to instrumentation and context. They push you back and forth in a world of sound where you can refresh your mind and learn something about life, or even yourself. That endless flow of repeats and near-repeats into which, despite the unpleasant characters and dramatic events that often await you there, you are only too willing to vanish. The art of repetition. John Coltrane also knew how to do that. His sheets of sound are pregnant tapestries of notes that break down a wall, lift a spirit and crack a skull or two. His later work would inspire artists like Terry Riley and it is there, with American minimal music, where things go wrong. Themes on step-and-repeat. After a few minutes, you can go for a beer because there is nothing else to hear. The anticipation for the next note completely sacrificed to the form. As to why repetition sometimes works and sometimes doesn't, one could devote more than a few thoughts. Few things are, for example, as exciting as a repeating, searing metal riff. A powerful musical mean of awesomeness that can maximise expectations but also can lose momentum if, in the context of the bigger whole, it lacks the tension that continues to feed curiosity. I can't help but think of this when I hear the new Metallica. After 40 years in the music business, Metallica are where they need to be and that, along with the respect they earn for that, is also a bit of a problem. They don't have to prove anything anymore. From an underground extreme metal band, they have become a band that fills football stadiums, a band you go to see with the whole family. To object to the band's development over all those years is to object to the fact that they still exist and you don't want that. Metallica are the Marines of Metal, "the first one in and the last ones out" as Scott Ian once aptly said. And you can hate them, as you can hate the Rolling Stones, because they are so settled in the collective memory, because they are so ubiquitous. But when they are on tap, they can still sound irresistibly delicious as the previous full-length album Hardwired... to Self-Destruct with Spit Out The Bone and Lords of Summer proved. So every time the boys of Metallica come out with new material, we look forward to it. As a band, why make the same record over and over again? Why keep evolving as a composer? Richard Wagner could have seen in his third opera Rienzi a formula for success, a basis on which he could mould new operas. But his ambitions prevented that (fortunately). Keeping yourself from changing is perhaps only possible if you are Slayer, Motörhead or AC/DC. In that context, it might be nice to compare Slayer with Metallica for a moment. If you have to choose between Slayer's first album or Metallica's Kill 'Em All, you choose of course Show No Mercy. Slayer all the way. Where Metallica on Kill 'Em All still sounds like a beta-cross pollination of Motörhead and Diamond Head, Slayer is in Show No Mercy already everything that makes Slayer Slayer. Superhuman speeds on guitar and drums that together with Tom Arraya's screams merge into transcendental trash. Had Metallica made the same record 10 more times after Kill 'Em All it would have been nice for those who accuse the band of selling out for more than 30 years now but also nothing more than that. Point is, Metallica had to change after Kill 'Em All because they were not yet where they needed to be. And look what happens next. With Hell Awaits Slayer takes a next step, sure, but Metallica jumps into hyperspace with Ride The Lightning, the mother of sophomore albums. Trash at superhuman speeds with challenging chord progressions in an exhilarating kind of musical drama; Metal Mayhem in an Epic-as-Fuck kind of way. Trouble is though, as the rest of their discography demonstrates, you can only make such a leap once in your career. The moment Metallica got to Master of Puppets, which is perhaps a bit of an overrated album (correspondence about this can be sent to Wagner & Heavy Metal, address: unknown), they have been caught up by the ever-slaying Slayer, who, with their third album Reign In Blood reach the top of the Trashmetal-Everest. The second big leap Metallica made was after Justice For All ... but the Black Album was more of a commercial than a creative breakthrough. And Load was not a jump as well as a descend into murky waters. (Load was necessary to reinvent themselves, to break free from the stranglehold and expectations of a fanbase that had found the holy grail of heavy metal in their first three, or four albums. It was a record that was needed to get back to making music on their own terms but musically it was, well ...). Trash at superhuman speeds with challenging chord progressions in an exhilarating kind of musical drama; Metal Mayhem in an Epic-as-Fuck kind of way. And now there is 72 Seasons, the eleventh album from Metallica in 42 years. A new Metallica is an event just as the release of yet another new remastering of the Solti Ring is an event. An event where the fun is in the anticipation (often more than in the release itself). The songs on 72 Seasons sound a bit thrashier than on predecessor Hardwire, without breaking speed records, and one will search in vain for the epic headbutt-metal of their first four records. At times, thoughts turn to (the aforementioned) Load and Reload. Albums with a kind of metalised hard rock. Albums that have their moments (Until It Sleeps, included in the live set again this tour for the first time in 15 years, is a very underrated song) but albums that, with the best intentions on earth, one can't finish in one, uninterrupted, listening session. 72 Seasons suffers a bit from the same shortcoming. Lux Aeterna, the first single, sounds kind of like Motörhead, but without the dirt (it sounds more like a Lemmy tribute than Murder One on Hardwire was). The first three songs of the album, the title track, Shadows Follow, Screaming Suicide are quite good as individual tracks but with track 4, quite appropriately called Sleepwalk My Life Away, listening fatigue starts to set in. Then the shortcoming wreaks itself that the band regularly pushes its songs beyond their natural length. Then the repetitions in the songs end up in a dead spot. Sometimes it happens that what sounds boring on first listen starts to grow over time and becomes a haunting listening experience (Harvester of Sorrow on Justice ...), but whether that's going to happen here I seriously doubt. The band sounds like they have been economical with ideas. Kirk Hammett relies mainly on the pentatonic scale for his guitar solos but in trying to say more with less, the results sound somewhat laboured and the inventiveness and atmospheric, neo-classical intros and bridges of math Metallica are sorely missed. Longing for things lost in time ... This summer, for the first time in five years, I am going to Bayreuth again. Back to the theatre that Richard Wagner had built especially for the performance of the ultimate cycle of rise and fall, Der Ring des Nibelungen. Looking forward to it. To a new production of Parsifal in which time becomes a space in augmented reality. And Tannhäuser, Tobias Kratzer's fantastic production that was supposed to have its last run of performances this year but is prolonged due to success. But more on that later, no doubt. - Wouter de Moor

|

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed