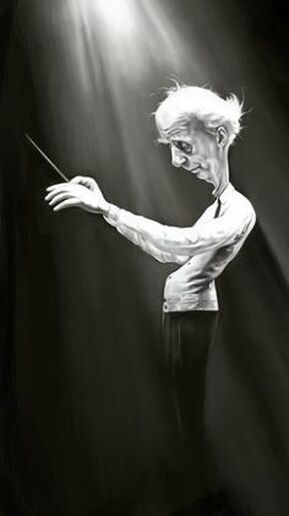

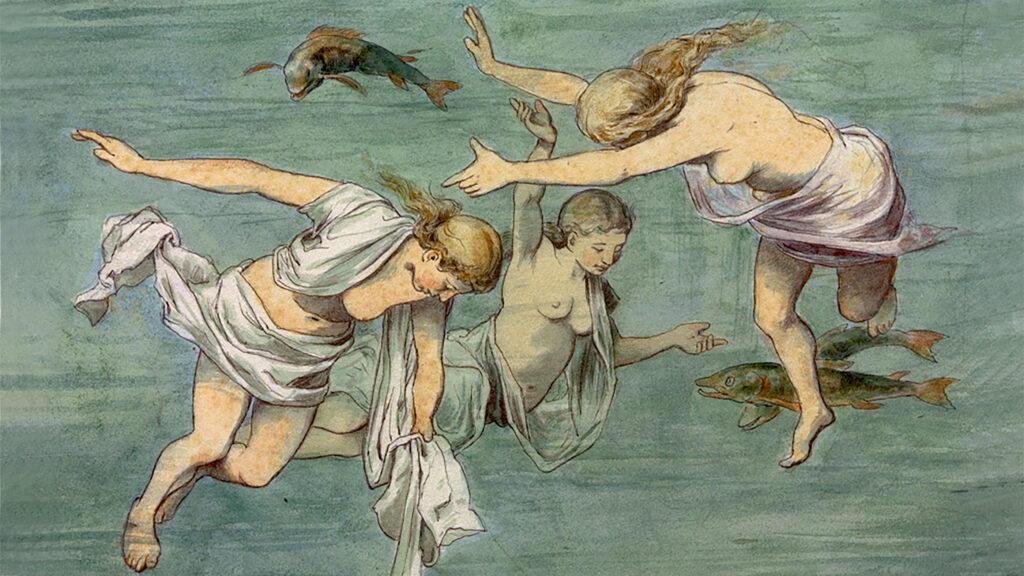

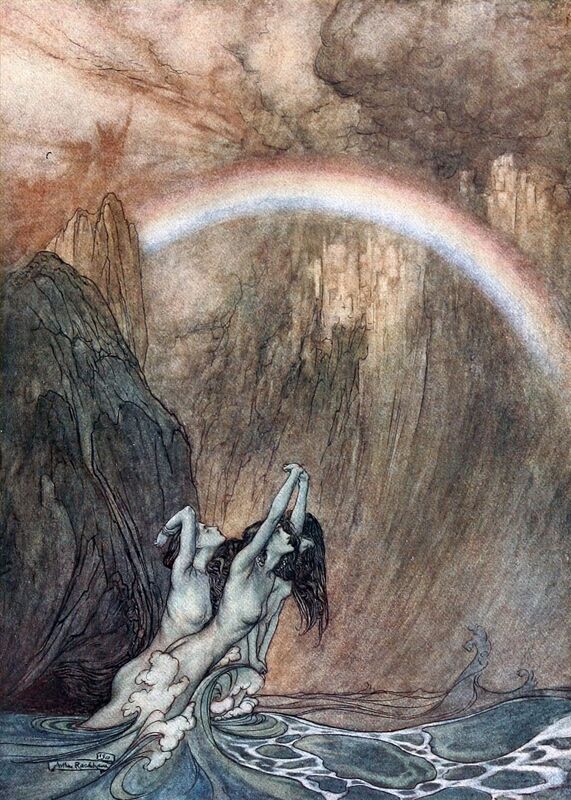

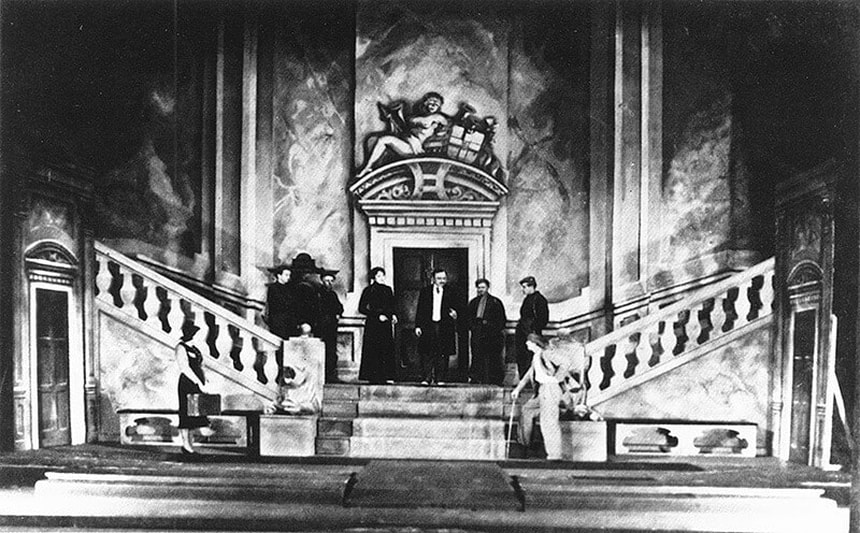

Seeking their inspiration at the source, Kent Nagano and Concerto Köln bring, with a 19th century instrumentarium, DAS RHEINGOLD to live in a most vividly, dramatic and enthralling performance. So it started as a joke. The Concerto Köln, which is well versed in Baroque music, asked conductor Kent Nagano if they would be willing to try their hand at a historically informed performance of Richard Wagner. The joke landed, one thing led to another, the baroque orchestra expanded from 40 to about 90 musicians, a full Wagner orchestra, and they set to work on the first of four Ring operas: Das Rheingold. After attending the eve of this Ring cycle, at a Saturday matinee, it can be said that the ambition, the effort and the study into an authentic Wagner have led to a very impressive result. The doubts about what exactly this 'authentic Wagner' should entail become irrelevant when you hear what Nagano has managed to achieve with the Cologne orchestra and a fantastic cast. The Wagnerian, who is only too happy to be lapping up yet another version of the master's musical dramas, listens to it with wonder and admiration. If this Rheingold is any indication of what is to come, he can look forward to a new, phenomenal version of Wagner's Ring. A Ring that will be much more than a curiosity, or just another addition to the Wagner catalogue, and a Ring that can measure up to the best that Wagner performance practice has produced so far. Nagano himself is confident enough about it: "I am sure that after this we will never play and sing Wagner as before." As part of the complete Ring, it generally has to settle for a place at the back of the pecking order when it comes to favourite Ring operas. As a stand-alone opera, it is not as popular as Die Walküre. But that Das Rheingold - that stepping stone to the rest of the Ring world, the introduction to the web of leitmotifs with which Wagner weaves his epic tapestry about the death of Siegfried and the downfall of the world of the gods - is an opera that can stand on its own two feet, is something Nagano proves with Concerto Köln in the most convincing way. It does Das Rheingold a service, it does historical music practice a service and above all, it does the phenomenon of live performance a service. Das Rheingold in the Concertgebouw was an ode to the stage, to the audience that comes together to experience live music. It was, after two years, a welcome back to a complete Wagner opera in the Netherlands. Das Rheingold was a new start for Wagner in every respect. After the Italian-lyrical Lohengrin, a musical point of arrival, he had to look for new musical means to do justice to the story of the twilight of the gods. With Das Rheingold, he built the foundations that were to underpin the rest of the Ring. Das Rheingold is special. Wagner wrote the libretti for his Ring cycle from back to front and composed the music from front to end. Das Rheingold is the Ring opera of which Wagner was the last to write the libretto and the first to compose the music. It is music that tells of a loveless world that has fallen into decay even before the first chord sounds. Decay that has been started by the pre-Rheingold actions of Wotan, who chopped off a branch of the world's ash to make his spear in which he would carve the laws by which he would subjugate giants, Nibelungen and people. Laws that will eventually bind him as well. Wotan gets a first, grim impression of the negative consequences of his lust for power at the end of Das Rheingold when he witnesses the fratricide of Fasolt, who is beaten to death by Fafner for that cursed Ring. He will eventually pay for his choice for power with his own love when, in Die Walküre, he is forced to withdraw his protection from Siegmund and subsequently deprives his favourite daughter Brünnhilde of her divinity. R. goes to the piano, plays the mournful theme 'Rheingold, Rheingold' [...] And as he is lying in bed, he says, "I feel loving toward them, these subservient creatures of the deep, with all their yearning." How does that sound? Wagner on period instruments? The answer can be answered in the affirmative. The brass sounds drier, more articulate and more defined. The strings sing with honeyed tones, highlighting concertante moments in the score of Das Rheingold with their warm-blooded character. The 19th century orchestra brings both nature to life - the Rhine in the prelude is less a homogeneous stream, more a water surface in which ripples can be seen - and the machinery of Nibelheim, in which the flute plays the role of a small wheel in need of a drop of oil. The Wagner orchestra, that entity that can give voice to everything in life, in its 19th century incarnation magnifies contrasts but does so by organically connecting everything in Wagner's sound world. Nothing exists without the other: grandeur and finesse, power and vulnerability (at times, the instruments sound like imperfect predecessors of their contemporary offspring, then it is as if Wagner is not only battling with the opera conventions of his time, but also with the limitations of the instruments at his disposal). It is a tapestry of sound that you can zoom in on at any time to discover something new in it. The period instruments shed new light on the wonder of Wagner's orchestration. But even more striking than the sound of 19th century instruments is the treatment of the text. Here, the emphasis is on audibility and the Sprechgesang is sometimes reduced to speech. As if Wagner had anticipated Kurt Weill; as if Arnold Schoenberg had taken his Sprechstimme for Pierrot Lunaire directly from Wagner. It is an approach that will undoubtedly divide opinions, but the expressive result is completely self-evident. At tea he said that, if he wanted to make things easy for himself, he would, from the moment Wotan says [in Die Walküre] , "Seit mein Wunsch es will," introduce recitative, which would certainly create a great effect, but would put an end to the work as art. With a concert performance of Das Rheingold, we had to rely on text, singing and music. It made, in this very vivid performance, with all the subtext that Wagner puts into the libretto and with its strongly imaginative music, a listening experience that felt like a full-blown production. This concert performance was a theatrical experience that provided a reassuringly non-coercive answer to the age-old question of "what images to add to Wagner's music dramas?" It was perhaps even better this way; the hall and stage of the Concertgebouw as a stage image, as a host for our own imagination. For what production concept would have done justice to what orchestra and singers presented to us here? That part of the Wagner theatre, the staging, was still in its infancy at the time of the master's death, and since the end of the 19th century, the questions that the Wagner drama posed to its theatre-makers have perhaps provided more unsatisfactory than satisfactory answers. It was as if Wagner had foreseen this, so explicitly and elaborately did he stuff his libretti full of descriptions of the action. As if he did not dare to rely on the directions of a theatre maker. It makes the music dramas of the Sorcerer of Bayreuth, more than any other composer, suitable for audio-only experiences. “I was startled by the work's power. On records, where there are no problems of staging to solve, one begins to sense how splendid the musical construction and the constant inspiration in this unique work really are. Even though we must admit that records in general are a poor substitute for the communal experience of a concert, at least in Wagner's case, such a recording as this has its advantages. It serves the music as well as any stage performance.” (Wilhelm Furtwängler after recording his -monumental- Tristan recording in 1952 with Kirsten Flagstad and Ludwig Suthaus) As a conductor, Kent Nagano has dealt with Wagner before. Solid readings of, for example, Lohengrin and Parsifal in Baden-Baden (with stagings by Nikolaus Lehnhoff) that betrayed craftsmanship but did not immediately stand out. What he does here can, certainly in that light, be considered nothing less than a revelation. A swift and inspired reading, with maximum attention to dynamics. Speeding up where possible (the descent to Nibelheim is a roller coaster) and slowing down where it suits best (Erda's warning to Wotan, a beautiful role by Gerhild Romberger, sung gracefully and with empathy). Everything with maximum dramatic impact. With his choice of tempi that serve the story and not the clock (as it should), Nagano clocks this Rheingold at less than 2 hours and 15 minutes, certainly one of the fastest performances in the Wagner performance practice, but still nowhere near what Wagner himself, no doubt exaggerating to make a point, once suggested for the ideal length of Das Rheingold. Timings DAS RHEINGOLD: The word 'authentic' is often misused, associated with a visit to a museum, in order to impose a fixed, solidified idea of how a composer's work should sound. The good thing about the merits of a performance, and ultimately the only thing that counts, is the result that is experienced. And that result completely pushes aside any questions about the authentic validity of this performance of Concerto Köln and Kent Nagano's first Ring opera. (And let us not forget that where the authentic Wagner is concerned, it was Wagner himself who placed, for the theatre he built for the premiere of his Ring, the orchestra under the stage - so much for this 'authentic performance' with singers in front of the orchestra on the stage). This performance of Das Rheingold is a feat with only winners: the orchestra and conductor and the singers. Without exception does the cast claim a leading role. Derek Walton is a wonderful Wotan, the supreme god who in his vexation for power lets things run their course, relies on Loge when it comes to paying for the construction of Valhalla, and repeatedly allows himself to be caught in youthful overconfidence. Loge, in turn, is a fine role by Thomas Mohr who gives the fire god a nice air of mockery and detachment. The fire god, in the service of the gods, who first foresees the end of the world of the gods. As Fasolt, Tijl Faveyts is the giant with a small heart. His love for Freia betrays not only lust, but also a longing for a domestic, conjugal life. Christoph Seidl's Fafner is robust, a giant with a powerful voice, menacing and invasive, fitting for a man who beats his brother to death out of greed. Stefanie Irányi as Fricka is the woman for whom Wotan, as he himself states, sacrificed his eye. Irányi sings Fricka, who in Die Walküre is often portrayed as an evil genius, with a sensuous combination of warmth, strength and concern. The rainbow bridge over which the gods enter Valhalla and with which the conclusion of Das Rheingold is initiated, finds, through a powerful performance by Johannes Kammler as Donner, together with the magnetising sounds from the orchestra, its dream interpretation - a tantalising image, a building extracted from the mind that is like the most beautiful staging.

DAS RHEINGOLD (Concertgebouw Amsterdam, 20 November 2021) Kent Nagano (conductor) Concerto Köln Derek Welton (Wotan) Johannes Kammler (Donner) Thomas Mohr (Loge) Tansel Akzeybek (Froh) Stefanie Irányi (Fricka) Sarah Wegener (Freia) Gerhild Romberger (Erda) Daniel Schmutzhard (Alberich) Thomas Ebenstein (Mime) Tijl Faveyts (Fasolt) Christoph Seidl (Fafner) Ania Vegry (Woglinde) Ida Aldrian (Wellgunde) Eva Vogel (Flosshilde) - Wouter de Moor

2 Comments

Michel van Aa’s latest opera explores the transhuman existence. A life in cyberspace without the burden of a physical body. Homo Deus in the Blockchain. The road to heaven, the place where you can drift eternally in supreme bliss, used to lead via the church, via God - now it leads via technology. UPLOAD by Michel van der Aa - composer and multimedia theatre maker - tells the story of a man who has his brain uploaded to the cloud. In saying goodbye to his physical existence, he hopes, along with filtering out his traumas, including the death of his wife, for an eternally happy existence on the network servers of the blockchain. UPLOAD saw its theatre premiere postponed due to the pandemic. It was released as an opera film (viewable on medici.tv) but as a live event, we had to wait almost a year and a half for it. The reality of Covid, where we were thrown back to our computer screens to see our colleagues, family and friends, provided a kind of preview. We noticed what we were missing when we were cut off from the outside world and communication had to take place without tactile experience. UPLOAD is about the answer to the question what remains of a human being when you separate the mind from the body. What exactly is the relationship between body and mind? To what extent does one influence the other? For example, does the mind know hunger and lust, once stripped of its physical ballast? At first, the man (the father) is happy with his bodiless existence (as if he has entered a dream of Arthur Schopenhauer by withdrawing from the world of physical burdens and lusts). But he encounters his daughter's incomprehension and grief. For her, the physical aspect of their relationship is vital. She can no longer hold his hand. Where are those hugs that go way back to her times as a little girl? "Scanning a brain to copy a personality is like digitising a Stradivarius to listen to Bach," she tells her father. From Bach to Blockchain and back. With a daughter who is estranged from him, the father feels increasingly unhappy and finally asks his daughter to pull the plug on his digital existence. The mind may be autonomous, but it can certainly succumb to loneliness. Scanning a brain to copy a personality is like digitising a Stradivarius to listen to Bach Richard Wagner brought together the various art forms of his time (besides music, painting and set design) in a Gesamtkunstwerk. What paintings were in the 19th century, film and video are to the 21st century and in UPLOAD (in Van der Aa's work for that matter) they form an integral part of the performance. Whereas Wagner did not escape the primacy of music (he therefore would abandon the term Gesamtkunstwerk), here film and multimedia are part of an end result in which all the separate parts take up a proportionate share of the greater whole. No single part pushes the other part away. A Gesamtkunstwerk, in the true sense of the word, for the 21th century. The multimedia spectacle in UPLOAD gives new content to the concept of opera, adds new dimensions to it. It provides spectacle, food for thought and a promise for the future. Here, technology is not a gimmick or a gadget, a forced attempt to make something of the past relevant to the present, but inalienably instrumental in telling a story about the here and now (and a possible near future). The result is organic and, despite the focus on a transhuman digital existence in cyberspace, deeply human. The father is played by Roderick Williams who sings the role live in motion capture cameras. We see the pixelated result of him communicating with his daughter who is played by Julia Bullock. She has the most lyrical vocal lines of the opera and a beautiful aria as well: "This is where you are now". The vocals are electronically amplified and distorted but the result remains organic throughout. They are part of a music that, in this multi-layered piece of music-movie theater, triggers its own variety of interpretations. It seems as if the instrumentarium (hectic, multicoloured, electronic and analogue, live and from tape) together with the vocals expresses the duality of body and mind. With the instruments as the physical processes and the vocal lines floating ethereally over them, as if they were the sounds of the world of the mind. No obvious chord progressions, but exciting music that is performed by the Ensemble MusikFabrik under the direction of Otto Tausk with great precision and vigour; the live music must coincide with the recorded music, and in the result, it is hardly possible to hear what comes from tape and what comes from the orchestra. The result does not take away anything of the immediacy of attending a live performance. UPLOAD is a Gesamtkunstwerk, in the true sense of the word, for the 21th century UPLOAD is told by singing, onstage acting and footage. On film, we see a flashback, shots in which we are explained what has preceded. At the place where the uploads take place - sanatorium Zonnestraal in Hilversum - we see a CEO (Ashley Zukerman) and a psychiatrist (Katja Herbers, who appeared a.o. with Zukerman in the series "Manhattan") explain how the procedure of uploading works. All the information in the world is digitally stored, except the contents of a brain. "Until now," they say and it becomes clear from their stories that technology is not going to wait for laws and regulations and will not answer (eagerly) to questions ethical in nature. If it can happen, it must happen. The urge of an ever-present need for change (not infrequently prompted by monetary gain) pushes forward what perhaps might best have been put on hold. It goes wrong in the case of the father. Instead of the upload filtering away his traumas, the grief over his wife's death remains. He is doomed to live with it forever. He asks his daughter to pull the plug out of his digital existence. Whether the daughter does so remains open. The play ends with a projection of father and daughter on the eve of the upload. It is a projection on a canvas that stretches from the second ring of the hall over the heads of the audience, with mighty visual results. UPLOAD is a brilliant piece of musical theatre that gives us a glimpse into the future - not only of humanity and science, but also of what an opera in the 21st century can be. It sends us home with more than a few questions. What does it mean to be human? We contemplate it over a glass of wine, consider the desirability of an existence as a Digital Homo Deus, while our bodies sink gently into an easy chair. UPLOAD (Dutch National Opera, Muziektheater Amsterdam 3 October 2021) Dates: 1-8 October 2021 Libretto, music and direction: Michel van der Aa Conductor: Otto Tausk Ensemble MusikFabrik Decor and light: Theun Mosk Costums: Elske van Buuren Dramaturgy: Madelon Kooijman & Niels Nuijten Father: Roderick Williams Daughter: Julia Bullock - Wouter de Moor

Opera Ballet Vlaanderen celebrates its return to the theatre with an exuberant production of Kurt Weill's DER SILBERSEE There was something to celebrate in Ghent last Saturday, when Opera Ballet Vlaanderen kicked off the new season in an almost sold-out hall with Kurt Weill's Singspiel DER SILBERSEE. After having seen its way onto the opera stage cut off for more than a year and a half by the pandemic and its related measures, the Belgian opera company once again presented a fully staged opera. Der Silbersee was the last piece Kurt Weill would make in Germany. After the Nazis had banned Der Silbersee from the stages, Weill first made his way to Paris and then to America, where he became an American citizen in 1943 and where he died in 1950. When Kurt Weill died, he knew no better than that the scores of Der Silbersee had not survived the book burning by the Nazis in 1933. That turned out not to be true, but Der Silbersee remains, to this day, a seldom-played piece. That is a pity because it contains beautiful pieces of music. In addition to Weill's well-known mix of classical music, cabaret, variety and jazz, the score contains choral singing that comments on the action and concludes the piece. It is an ending in which a chorus of ghosts accompanies the two protagonists, Olim and Severin, in their flight with a text that expresses hope. "Wer weiter muss, den trägt der Silbersee" (He who must go on will be carried by the Silver Lake). Both men are determined to drown themselves but, despite the sudden onset of Spring, the Silver Lake turns out to be frozen. It is an ending in which both men face a future that is uncertain but which suggests a spiritual redemption. Unlike, for instance, its predecessors Dreigroschenoper and Mahagony (which Weill created together with Bertold Brecht), it is not only the protest and the political satire that the audience is sent home with; the piece ends with a plea for humanity and hope. And the circumstances in which Der Silbersee was created played no small part in that. When Kurt Weill died, he knew no better than that the scores of Der Silbersee had not survived the book burning by the Nazis in 1933. When Der Silbersee was premiered in 1933, the Nazis had come to power just under three weeks earlier. The premiere took place simultaneously in three cities (this was not unique, in 1920, Korngold's Die Tote Stadt had its premiere in two cities simultaneously, but it was exceptional, a sign of Weill's popularity). Nationalism and anti-Semitism, which had been raging through the country for some time, found a perpetuation in Hitler's accession to the office of chancellor that would put an end to many things in Germany, the most basic decency to begin with, and one of the first victims of the Nazis' purge was the art that was considered un-nationalistic and cultural-bolshevik. In Der Silbersee, Weill and lyricist Georg Kaiser were unequivocal about the threat posed by the new authorities and their followers - they had very little compassion for people who had resorted to fascism as a solution to their problems. The Ballad of Caesar's Death from the second act, in which it's mentioned that Caesar wanted to rule with the sword but was killed by the knife, was with its direct reference to Hitler reason enough for Goebbels to pull the plug on the series of performances. After 16 shows, Der Silbersee disappeared from the stage.

The hunger, however, proves persistent and resurrects from the grave that was dug for him. The scene is interrupted, it becomes clear that we are watching a play in the rehearsal phase where, by way of trail & error, different concepts are being tried out. It is the starting point for the actors to regularly step out of their roles and where the boundary between the role they play, as actors in Der Silbersee, and the comments they make as "themselves", becomes diffuse. The science-fiction opening is followed by an actualisation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, we see the nouveaux riches as Egyptian pharaohs and there are references to Chinese opera. The "Ballad of Caesar's Death" from the second act, in which it is mentioned that Caesar wanted to rule with the sword but was killed by the knife, with its direct reference to Hitler, was reason enough for Goebbels to pull the plug on the series of performances. Der Silbersee is a story about social injustice, guilt, penance and forgiveness. Police officer Olim (Benny Claessens) shoots a thief, Severin. When it becomes clear that the thief has stolen only a pineapple, Olim's conscience starts to bother him. If only he had money, he sighs. It is fortunate that he then becomes the owner of a castle by winning a lottery. In the castle, he takes care of Severin; the relationship between the two is one of unrequited love. Severin does not know that it is Olim, the man who now claims to be his benefactor, who has crippled him. Severin (a strong role by Daniel Arnaldos) continues to seek revenge and Olim sees his efforts to heal Severin and seduce him into love, fail because Severin has built a wall of bitterness around himself. Meanwhile, Frau Von Luber (Elsie de Brauw), the former owner of the castle, tries to get her hands on the keys of the castle again with the help of her niece Fennimore. It is Fennimore who helps Severin reconcile with Olim when Serverin has found out that it was Olim who shot him, and she accompanies the two, we hear her voice along with the chorus, on their flight to the Silver Lake (a Parsifal-like ending with the promise of redemption, the chorus of prisoners from Beethoven's Fidelio also comes to mind). Fennimore is a fairy-like character who, in this production, is interpreted by two people: Marjan De Schutter in a talking role and soprano Hanne Roos. Mondtag places this new production in the year 2033, exactly one hundred years after the premiere of the original play. In this (future) world, an extreme right-wing party, The Iron Front, threatens to seize power. It threatens the production of Der Silbersee and splits the minds of those concerned how to deal with this threat. Mondtag is a man of exuberance, the carnivalesque and the cartoonesque, but also someone who tends to overplay his hand when it comes to proclaiming a message and then starts stating the obvious. Even without the trick of bringing the play up to date, of moving it to a future that mirrors the time of its premiere, the similarities between the present day and 1933, the time when Der Silbersee premiered, are strikingly clear. In a play where the music and songs are meticulously placed within the text by the composer, it would have saved a lot of (superfluous) dialogue if he had just limited himself to telling the original story. In a rarely performed piece like Der Silbersee, this would probably have been more logical. Mondtag's direction gives the actors a lot of space (too much space?) and Benny Claessens in particular grabs that freedom with both hands. That must have been premeditated. Claessens and Mondtag know each other well; they previously worked together at the German Gorki Theater where, among other things, they placed a version of Oscar Wilde's Salome in the same queer perspective as they do here. That queer perspective adds an extra layer that almost suffocates an already richly layered piece. The added texts, a part of them originating and based on actual texts from the creators' correspondence in 1933, are spoken in German, English and Dutch (languages between which Claessens switches impeccably). They might have benefited from a good edit for the progress of the play stagnates more than once. Brechtian alienation, actors stepping out of their roles, coincides with irritation about the carnivalesque cabaret that Der Silbersee lapses into from time to time. Cabaret that flattens the layering of the (political) seriousness of the lyrics and the multi-coloured music. The connection between the lyrics, that tell about hunger and oppression, and the music that mixes classical, cabaret, variety and jazz, makes the musical part of Der Silbersee of a stratification that is not adequately conveyed by the production. The cabaret to which the actors too often resort breaks right through the tension that has been so cautiously built up by Georg Kaiser's texts and the diversity of Weill's music. Music in which conductor Karel Deseure, in an inspired reading, full with expressive brass and pregnant percussion, holds all the various facets of the score together and pushes it forth with great forward-moving power. It is a parade of colourful (and noisy) characters who, in all their exuberance, set the tone of this production. An exuberance that connects more with the reality of being able to visit the theatre again than it does with the political fairytale of Der Silbersee. Thus, within the play of a play, this Silbersee became part of an even bigger play. The play that took place in the real world where a return to the theatre could (finally) be celebrated. A return to what was once normal, but never taken for granted because it was always special. It was a resurrection of the wonders of the living stage, place where we celebrate, relate, interpret and give meaning to life. The 2D of the streams of the past year and a half was exchanged for the 3D of theatre in flesh and blood. It was of a joy that surpassed the vivacity of the queer and camp on stage. DER SILBERSEE (Opera Ballet Vlaanderen) Dates: Ghent 18 sept, 21, 24 & 25 sept, Antwerp 3, 7, 10, 13 & 16 october Direction: Ersan Mondtag Conductor: Karel Deseure Severin: Daniel Arnaldos Olim: Benny Claessens Fennimore: Marjan De Schutter / Hanne Roos Frau von Luber: Elsie De Brauw Lottery agent & Baron Laur: James Kryshak - Wouter de Moor

An account of Parsifal in the church. Dutch director / bass-baritone Marc Pantus stages the third act of Parsifal in a place of grace. Wagner live! It happened after all in this Covid-year. A Wagner in flesh and blood. Wagner in a church with a chamber ensemble. "You have to do something", Marc Pantus must have thought, with the theatres closed in the last year and a half, and he made - a bit in the tradition of the St Matthew Passion that is performed every year in the Netherlands on and around Good Friday - a Parsifal for the church. In a special production came the third act of Wagner's last opera, already a kind of synthesis between a Passion and an opera, in an arrangement for chamber ensemble by Hugo Bouma. Not that you need to be reminded of it, of course, but what good, beautiful and layered music Parsifal is. A stratification in sound that remains effortlessly intact in an arrangement for piano, harmonium and synthesizer that, in the transformation scene, is assisted by four square gongs, a recording of the chorus from 1928 (by Karl Muck) and Kundry on bass (the latter not without a taste for the gimmick, it gives a momentarily band-vibe to the music). Three singers sing four roles, with initiator and bass-baritone Marc Pantus taking care of Gurnemanz and Amfortas, and Marcel Reijans singing (a superb) Parsifal. The whole thing is semi-staged, Parsifal in a nursing home. A place where people wait for death, for redemption. That salvation comes, when the grail is revealed. A moment when the lights go on and the Dominicus Church in Amsterdam proves itself to be the perfect setting for the Höchsten Heiles Wunder. In this environment, the question of whether Parsifal is a Christian opera or an opera that 'merely' uses Christian elements is almost more inevitable than usual, but we do not need the answer to that question in order to be fully immersed and to celebrate the return to 'Wagner in the flesh'. The last act of Parsifal is the last act of Richard Wagner's musical output. Death was already cautiously looking around the corner and Wagner hoped that time would allow him to finish his last opera, his Bühnenweihfestspiel. With Parsifal, Wagner has nothing more to prove; here, everything he had previously done is sublimated into the most subtle, beautiful music ever. With a special ear for the acoustics of his own Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, in Parsifal he allows the various instrumental groups to melt together, with melodies full of chromatic tension and dialectic delight flowing over an instrumental array of ambient and intoxicating sounds. A special role is reserved for the dissonances in the instrumentation, so crystalline brought to the surface in this chamber setting, which grants us a glimpse into the composition of Wagner's musical fabric; a sound carpet of unprecedented beauty that never ceases to fascinate. A music that distinguishes itself from a great deal of other music with epic ambitions that wants to be beautiful and outspoken, but forgets to be truly exciting in the process. After all, the ultimate result of something is the result of things that are not that result (I think somewhat pseudo-philosophically with 19th century sophistication). Parsifal, the opera about the pure fool who must bring redemption. As in Siegfried, ignorance is here a virtue that must unravel the knot of modern life or, better still, cut it rigorously. Parsifal is an opera about desire that must be suppressed. Here, giving in to lust, falling into sin, comes at a high price. It brings ruin to a community; it inflicts a wound that cannot be healed. Wagner has built an oeuvre on the search for Erlösung. The idea of redemption must have preoccupied him to a high degree, taking up a considerable amount of his time. When there is mention on the train of the Wagnerites' preference for Tristan und Isolde even over Parsifal, R. says: "Oh, what do they know? One might say that Kundry already experienced Isoldes Liebestod a hundred times in her various reincarnations."

That ending, when the grail is revealed, is accompanied by moistened eyes. It is a perfect soundtrack to the period of slowing down that the pandemic has forced us into. A period that with this Wagner production hopefully will come to an end. PARSIFAL, 3rd act (Dominicus Church, Amsterdam) Arrangement by Hugo Bouma Marc Pantus: Gurnemanz & Amfortas Marcel Reijans: Parsifal Merlijn Runia: Kundry + bass Daan Boertien: Piano Dirk Luijmes: Harmonium Andrea Friggi: Synthesizer & musical direction - Wouter de Moor

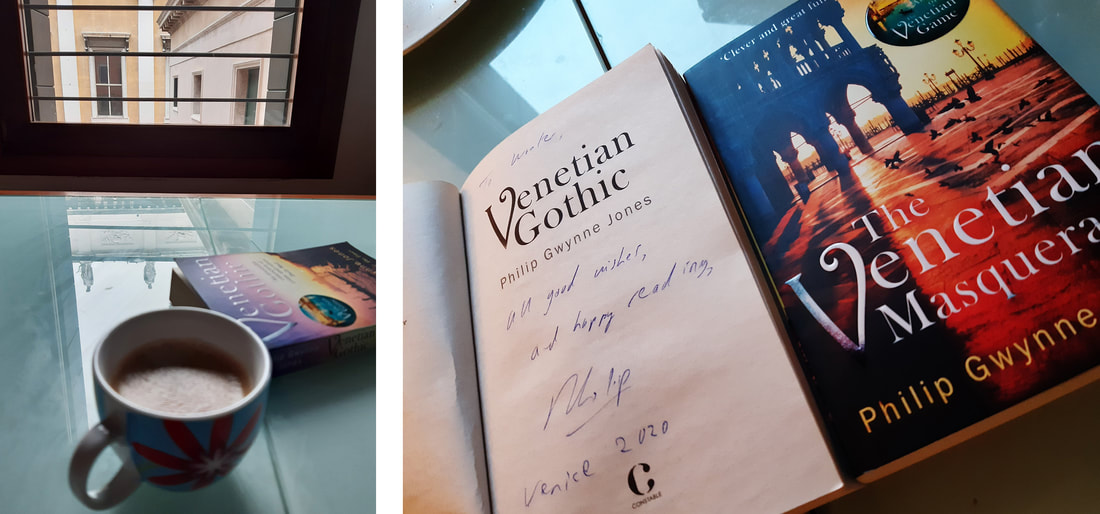

The winter is over. The Covid night not yet. The WAGNER & HEAVY METAL Spring Weblog steps into the light with a visit to Venice and meets up with a creature of the night. Reading time: 15 min A month after the premiere of Parsifal in 1882, Richard Wagner travels with his family to Venice to spend the winter there. In Venice, his health quickly deteriorates, he suffers a lot from spasms and he misses his books up there. But he does not think of going back, the idea of being locked up in the north (in Bayreuth) all winter makes him shudder. With the arrival of spring, the sun feels like a reminder of that inclination that can surface so strongly in winter. The inclination, that animalistic need, to escape the chilly gray of winter. Twenty-twenty, the year where everything came to a standstill, ended with a flight to Venice. A relocation to the city of the doges, magnet for artists, writers and composers. A relocation of the body to refresh the mind. The city, an open-air museum with its museums closed, with only a fraction of the number of tourists who normally roam there, became a setting for walks where Richard Wagner and Gustav von Aschenbach had left their real-life and fictional footsteps before they, for real and fictional, passed away there. The poetic potential of going to Venice at the time of a pandemic, city of the plague (quarantine) and cholera (Thomas Mann's Tod in Venedig), was not lost on us. Our stay became a sojourn in the city of gondolas and Acqua Alta (high water) where you felt the force of cultural heavyweights pulling at you without the need to draw that inexorable, ultimate conclusion. After more than a month we went home, without dying. Venice means a lot to a lot of people and the most extraordinary thing is that despite the seemingly endless influx of tourists who come here for the same thing, the city speaks to you in a highly individual way. That was what struck me most on my first visit two years ago. A visit to Venice has the immediacy of a live event where the massiveness of the audience does not get in the way of an intimate experience. A visit to Venice, instead of being an item on a bucket list that you tick off, was a place that you absolutely had to come back to. An introduction to a place that was more beautiful and fascinating than all the stories, photos and art could have prepared you for. As if behind the spugnatura texture of colorful walls and the amazing light (which Cosima writes about so admiringly in her diaries) there is a reflection and deepening of one's own emotional life. Beauty and decay are inextricably linked here, and nowhere more than here is it clear that decay, the ravages of time, the mortal aspect, is an inseparable part of what we experience as truly beautiful and valuable. Nowhere does decay look more beautiful than in Venice. Wagner had to do without (most of) his books in Venice. Nowadays, we simply take a library, more books than we can read in a lifetime, with us on an e-Reader. Indispensable for those traveling but in Venice, being with the books of Philip Gwynne Jones (and the author himself, a Spritz Venezia with Campari and no Aperol because that's too sweet) was a welcome reminder of the unsurpassed excellence of the paper book. Philip Gwynne Jones' paperbacks with relief covers (as good paperbacks ought to have) were a very fine tactile addition to the digital reading routine. Jones has lived in Venice for a decade, and his books bring together crime and culture. His stories are like tourist guides to the most beautiful city in the world in which a crime is committed. Stories that revolve around Nathan Sutherland, English Honorary Consul to Venice, and his girlfriend Federica. A man who spices up his conversations with his spirited girlfriend with nerdy details about music and film. It makes the adventures they have together all the more empathetic. It scores Nathan Sutherland, the man who, to his regret, does not share his birthday with Tony Iommi by only one day (-1), sees that somewhat made up for by the fact that he does share his birthday with that of Yoko Ono (+2), some bonus points on the list of nerdy coincidendes from yours truly, who shares his birthday with that of John Lennon (+10). "Are you sure Philip Gwynne Jones doesn't know you from way back?" my girlfriend asks me as she takes note of the passage below from "Venetian Gothic" after I break the living room silence with a hearty burst of laughter. Fede rested her head on my chest, and looked up at me. She raised her eyebrows, but didn't say a word. ‘Hawkwind,’ I said. ‘Oh’ “Assault and Battery". It's from Warrior on the Edge of Time. ‘Oh.’ She closed her eyes. ‘Were you single for a long time, Nathan?’ (Venetian Gothic, Philip Gwynne Jones) The scene above, together with the author's fondness for hardrock, opera and classic horror movies, might indeed suggest something like that. The scene is recognizable to the point of being uncomfortable. Books and stories can be like rabbit holes you disappear in when you hit the bookshelves or search on YouTube for that one novel or movie referred to. The same here. The happiness of scenes that remind one of what a person has read and experienced is amply provided for in the stories surrounding Nathan Sutherland (who couples his incisiveness in thinking with an acting in anti-James Bond style, when punches are dealt he is usually on the receiving end). The stories are a pleasant adventure novel-like extrapolation of the Venice you have come to know as a beautiful city where actually no murders are committed on a regular basis and are, in addition to being highly entertaining and very educational, a pleasant wander - far away from the all-consuming ordinariness that everyday life can be so burdened with. ‘Welcome to my home,’ she said. ‘And leave something of the happiness you bring,’ I whispered to Federica. ‘What's that?’ she asked. ‘It's from Dracula.’ (The Venetian Masquerade, Philip Gwynne Jones) Ever since I read the book (at the age of 13 during a holiday in France, on a camping near an old castle) it has been among my favorites. A book in which the evil depicted is so chilling because it remains, for a large part, hidden from view. It is perhaps for this reason that no film (entertaining though they are) has ever been able to do full justice to the story that Bram Stoker constructed in his epistolary novel around the chief of all vampires: Dracula. The conversion of the epistolary novel into an anecdotal narrative in which the many narrative perspectives are exchanged for the single perspective of an omniscient camera does not do justice to the fantasy to which the book so successfully appeals. In the book, Dracula finds himself on the convergence lines of several points of view. He becomes visible in the traces he leaves behind, described in letter fragments and newspaper clippings. The link between the horror and the man, the creature, we have come to know at the beginning (through Jonathan Harker's diary entries) becomes clear only later. A new Nosferatu by Robbert Eggers is planned (which draws on Murnau's 1922 film) but perhaps director Karyn Kusama (Jennifer's Body and The Invitation) will find the key to the ultimate Dracula film. She has a Dracula film adaptation in the pipeline that, being the first, takes the premise of the different narrative perspectives from the book as its starting point. In writing Dracula, Stoker was actually aware of the theatrical potential of his master vampire. Stoker was a man of the theater himself and managed the Lyceum Theater in London, headed by Henry Irving, an actor whose intense portrayings of diabolical roles (amongst them The Flying Dutchman) were a source of inspiration for Dracula. Since then the chief vampire made his appareance in a wide variety of stageplays, movies, musicals, an opera (by The Royal Swedish Opera) and a ballet. Guy Maddin, Canadian cult director (The Forbidden Room was one of the best cinematic experiences of recent years), ventured in 2002 with a film adaptation of a ballet of the Dracula story (Royal Winnipeg Ballet's interpretation of Bram Stoker's book) and came a long way when he fused silent-film techniques, avant-garde imagery and music by Gustav Mahler into a 21st century theater of Gothic Grand Guignol. The vampire in Dracula: Pages from a Virgin's Diary is of Asian origin, and in that guise he carries with him not only the cross of the vampire but also the cross of the foreigner. In this Dracula adaptation, the deeply human characteristics in a being from another, inhuman dimension, are embedded in a current social and societal framework. This widens the image depicted of the chief vampire; he is more than just evil. Guy Maddin provides his Dracula with atmospheric images (he has that in common with other Dracula films) and relies on the power of suggestion with the abstraction of a ballet choreography. It doesn't get as good as the book (obviously) but the imagination of the book finds a worthy counterpart in Maddin's imaginings. The vampire condemned to wander eternally in the underworld shares his fate with that of the Flying Dutchman. Trapped by a curse that forever bounds them to the earth, they withdraw from the world of the living and the rules that govern it, in order to seek relief and salvation from someone, preferably a woman, who makes herself available (voluntarily or by force) for the purpose of supreme liberation. In this (very Wagnerian) premise, the woman, in the brisk combination of being both commodity and savior for the man, may indeed rejoice in her indispensability, her personal ambitions will not have to extend beyond being subservient to the man (synonymous with how Cosima put her life at the service of Richard Wagner and his genius, and saw that as her highest possible goal in life). In all my sad thoughts about life I am always uplifted by the knowledge that it was permitted to me to become necessary to him. Cosima's diaries - 22 Nov 1870) Where Richard Wagner's influence in music was considerable, his influence outside of music was possibly even greater. There was not an artist at the end of the nineteenth century, beginning of the twentieth, who did not emerge from under his shadow; his presence was ubiquitous. No wonder that Wagner's ideas about theater, music and drama ushered in the then new medium of film at the beginning of the twentieth century. The Dracula film that would be at the foundation of a genre not excluded. #1 Scene from "Dracula" (Tod Browning 1931) In what may have yielded the best-known Dracula to date, the 1931 Tod Browning film in which Bela Lugosi shaped the Transylvanian vampire with an affectionate accent, we hear the overture from Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg as Dracula visits the opera (see clip #1). Simultaneously with the version for the English-speaking market, a Spanish-language version was shot (directed by George Melford). In that Spanish-language version the character of Dracula is a lot less successful in becoming a movie icon but the editing of the film is superior to its English-language counterpart. Also in the Spanish version, Dracula goes to the opera but more than in the Tod Browning film, the music of overture Meistersinger is here not just a reminder that we are at the opera, a musical fragment as a leitmotif, but a serious host for the dialogue that takes place over it. (Apparently, the overture of an opera is the appropriate time to engage in extensive conversation.) #2 Scene from "Dracula", the Spanish-language version (George Melford 1931) Both Meistersinger and Dracula present us with the woman as an object of desire and as being a savior. And in both Dracula and Meistersinger, it is the father who exposes his daughter to evil and/or danger by respectively introducing her to Dracula (see clip #2) and awarding her to the winner of a singing contest. In Dracula, it is Mina who is 'privileged' to enjoy the special interest of the title character. In Meistersinger it is Eva who revels in the interest of several men of whom the interest of Beckmesser leaves the most unpleasant aftertaste. He is not seen (only) as a Jewish caricature anymore (a character of lesser morals) but in Beckmesser's interest in Eva, versus Walter's feelings for Eva, low intentions against those of true, pure love become visible. In the Spanish-language version, as if in coupling with Meistersinger, "Mina" is called "Eva”. It is as if, with the music of, and reference to, Die Meistersinger, the filmmakers want to tell us something about the similarities between the story and the characters in Dracula and in Meistersinger. Perhaps the filmmakers want to point out to us, the audience with knowledge of opera, the similarities in the fates these two women share in both film and opera. Coincidence or not, we Wagnerians who always like to see the grasping claws of the master reach as far as possible outside the realm of his own operas will of course gladly accept the invitation to draw conclusions about this commonality. Both Meistersinger and Dracula present us with the woman as an object of desire and as being a savior. With what Dracula can tell us about Meistersinger, we let our light shine on the motives of two male characters in the opera. It is difficult to perceive in Beckmesser, the master singer who manifests himself as a charlatan, noble motives for his actions and his desires. He is, at first glance, best suited to the role of the proverbial leech, the man who parasitizes on the skill of other people. If Beckmesser is Dracula then Hans Sachs is the most appropriate person to be Van Helsing. in Bram Stoker's book, Van Helsing is a man who carries along his own mania. He is aware of the contradiction that only superstition and delusion can point the way back to the normal world. As a fighter of creatures that belong only in legends, he engages in his own kind of Wahn, Wahn, überall Wahn. But to confine ourselves to the Beckmesser-Sachs tandem as a vampire and its hunter would ignore the fact that the character of the vampire, in all its multicolored greyness, has gained in substance throughout time. Why not give it a twist?

What if Hans Sachs, once night has fallen, leaves his home to indulge in innocent virgins? Abusing his position as a distinguished citizen in order to do the very thing he seems to have renounced for the eyes of the outside world. Well, in a world where Pride & Prejudice and Zombies exist, there surely is room for Meistersinger und Vampire. There is another, not fictional, but historical link that connects Dracula with a Meistersinger in Nürnberg. Before the real Hans Sachs, master singer and shoemaker, was even born, a poet named Michael Beheim lived and worked in Nürnberg. He was a (proto-)master singer who lived from 1416 to 1472. Beheim was Germany's most prolific poet of the 15th century. At the courts he was a frequent and welcome guest. In 1472 he was murdered under undisclosed circumstances. Beheim lived in a time of Papist emperors, Protestant secessions, Turkish invasions, and pagan rulers in the east. One of those rulers was Vlad Tepes, one of the inspirations for Stoker's Dracula. In 1463, Michael Beheim wrote a poem (Gedicht über den Woiwoden Wlad II. Drakul), a master song, or at least a prototype of a master song about Dracul, Vlad Tepes III, a sadistic ruler who took pleasure in impaling his enemies, women and children not excepted. In order to properly enjoy the macabre scenes that resulted, Vlad occasionally enjoyed a meal next to his impaled victims. Mainly because of a sloppy translation of the poem it was that Beheim's poem about Tepes and his barbaric savagery gave the suggestion that Vlad, like his fictional afterbirth at the end of the 19th century, drank the blood of his enemies (giving Stoker the inspiration for a bloodsucking Dracula) but that is most likely nonsense (Stoker most probably wasn't even aware of Beheim's poem when writing Dracula). Not that there wouldn't be plenty of horror left without that proto-vampire bloodsucking. Washing your hands in the blood of impaled people while having dinner scores high enough on the ladder of psychotic behavior to make it into a legend. Beheim based his poem in part on the testimony of a Franciscan monk, Brother Jacob, who had survived Vlad's atrocities. The horror of which the poem reports was an illustration of the cruelty of the godless Vlad, who, in contrast to the true faith of the Catholic rulers of the day, added an exalted lustre to noble Christian morals. From: Gedicht über den Woiwoden Wlad II. Drakul (Michael Beheim)

The historical Dracula saw himself, in his lifetime, materialized in literature by a poet in Nürnberg. A minstrel, who lived in the generation before Hans Sachs. Centuries later, the music of the Meistersinger von Nürnberg, an opera that takes the historical Hans Sachs as its inspiration, would accompany Dracula as he makes his way to the opera in a movie that bears his name. May we ourselves be able to go to the cinema and theater again soon, at a time in the not too distant future. So that we can once again experience the immediacy and excitement of a live performance in a world in which we do not have to rely solely on the pixilated reality of streams on a screen (no matter how welcome they are). - Wouter de Moor

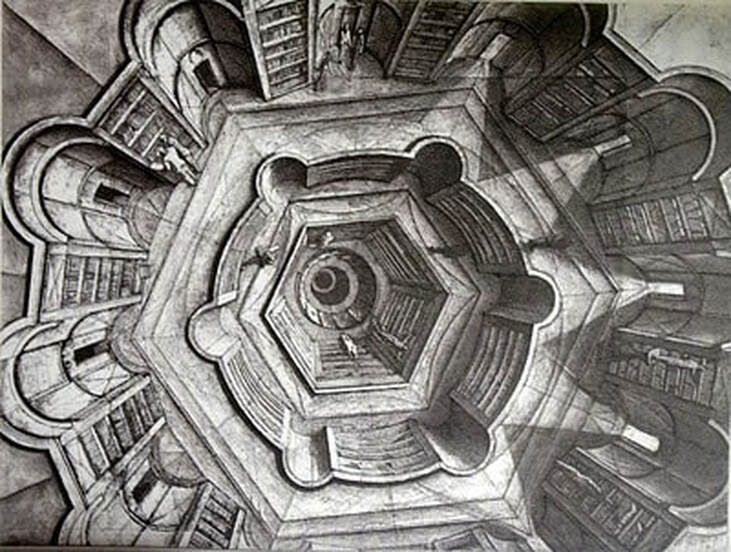

The WAGNER & HEAVY METAL WINTER WEBLOG on music, books and the light at the end of tunnel. From ' HEAVY' (Dan Franklin) to a heavy book 'WAGNERISM' (Alex Ross). Plus Wilhelm Furtwängler and (a lot) more. Reading time: 17 minutes It was March, a bat in Wuhan had the world locked down, and I dreamt that I walked into a large building, gothic in design, in which there were countless cases with books. I was in what must have been Borges’ idea of heaven: a large, infinite library where you can fill your head with what people, in their most sublime and intimate thoughts, had written down. At first the library was everything I could wish for, I devoured one book after another, but after a while (could have been years or centuries, dreamtime is hard to define) I noticed that the books no longer spoke to me. I was exhausted and empty. I filled my head but my body didn't follow anymore. Isolated from the outside world I had become a stranger to my own feelings. I could no longer relate to the events and emotions I read about in the books; I had nothing more to add to them. I, the introvert, needed the outside world to keep the mind oxygenated. Life needs maintenance, so the dream seemed to want to warn me at the beginning of the lockdown. While summer has turned into the grey, cloudy autumn and the blackened agenda of recent months (no MahlerFest, Bayreuth and much more) lies still heavy on the mind, we again, at least for a while, go into lockdown. Once again the road to the concert hall is being cut off and once again the man who is no stranger to spending time on the couch with books and music sees the new time with new unease. Will they all still be there when all this is over? The halls and theatres where we can attend concerts and operas? For me the ban on visiting concerts was recently broken by a chamber orchestra performance of Gustav Mahler's Fourth symphony. It was a Covid-concert - 12 men in the orchestra instead of 100, the hall filled for about 1/3rd, and a programme, in which Mahler shared the programme with Alban Berg (Sieben Frühe Lieder), that was played twice. Soprano of service was Barbara Hannigan. I gladly gave up my reservations against coming together in confined spaces during times of Covid. The return to the concert hall was special. An occasion where the music testified that everything of value is ultimately more vulnerable than you would like to think. It was remarkable (and kind of funny) that the performance by a chamber orchestra of a symphony written for large orchestra bore in it the sense of improvisation that synchronized with the character of the concert (making the best of a situation). No preoccupations with things like tempi and the ideal balance of instruments. More than listening to a piece of music you know from your preferred (recorded) renditions, it was like listening to your favourite band performing in an unplugged session. Mahler’s Himmlische Leben, the heavenly life, was, as expected, in joyful, glowing hands of Hannigan. But it was the Adagio, initiated by a cello, full of bromide and brooding desire, that was exceptional. It built a bridge between two worlds; a bridge between the world during and the world before the pandemic. The Adagio connected with the last concert I visited before the lockdown: Mahler's 9th symphony in February. You don’t have to hear a premonition of death in the Adagio of that symphony, six months later it acquired nevertheless the depth of a farewell for me (Stephen Johnson argues in his book "Symphony of a Thousand: Mahler and the World in 1910" convincingly that this is not Mahler's farewell to the world and makes, even more than he does for the 8th, a case for the 10th symphony). The dissonants of the Fourth, a beauty not yet complety smoothened, rubbed against the dissonants of the Ninth. The sound of the cello cast a glance on the world of yesterday. A world of which you could not imagine it would ever be exchanged for another. With the relative lightness of the Fourth, the tragedy of the Ninth became even more poignant, once again palpable; it was the symphony that the composer was never able to hear in life. The time to deal with matters of eternity is limited for everyone. (And then, while writing this blog post, I heard that Eddie van Halen had died. Stunning silence).  Mahler, the name on the bill was like a leitmotif. An indication for drama with which one purifies heart and soul. Mahler as a leitmotif, a word with gravitas; a pointer for feelings that directed me back to the concert hall. My late father found Mahler scary. He identified him with Romanticism, the macabre side of it. Who writes something like Kindertotenlieder? It kept him away from the German/Austrian Romantics until, late in life, he heard Lohengrin and concluded that he had apparently missed something of indelible beauty. In 1904 Mahler completed Die Kindertotenlieder (songs on texts by Friedrich Rückert about the death of young children) - it was for Alma like provocating fate. Four years later their daughter Maria died. In the long life that would have befallen her (she would die in 1964, she would survive Mahler longer, 53 years, than Mahler had become old), Alma Mahler never wanted to hear Die Kindertotenlieder. With Skeleton Tree from 2015, Nick Cave wrote a kind of his own Kindertotenlieder. It's an album with lyrics about loss and death that seem to creepily precede the death of his own child. (When the recordings for the album were almost finished, Cave's 15-year-old son, Arthur, fell off a cliff). In HEAVY, the book in which Dan Franklin shines his light on matters of gravitas in the world, the name Nick Cave is mentioned by Phil Anselmo, former front man of metal band Pantera. His journey along the fringes of existence brings Anselmo alongside extensive drug abuse to the art he considers substantial – ‘heavy’ if you like and Nick Cave is as heavy as one can imagine. Just as a lowering of the tempo does not automatically mean that music becomes more dramatic (the thoughts almost automatically go out to Reginald Goodall's Parsifal, the only Wagner recording in my possession that I can't get through), decibels are no guarantee for heaviness. Heavy is in the character, in the intention, in the source of where the music comes from. Heavy is the foundation on which indefinable feelings find solid ground. There is certainly a physical aspect to Heavy where overdrive guitars and rolling bass drums can come in handy but Heavy doesn't forget to connect large gestures with intimate feelings. Heavy has a feeling for theatre and Heavy knows that drama can't do without beauty. (Yes, opera is heavy). Heavy absorbs the punches, is an airbag for the blows inflicted by life. Heavy turns that which one feels insecure or ashamed of into a fist with which one can attack the world. Heavy is the joy that lurks in a minor chord, the profound pleasure that comes from listening to gloomy sounds and discovering that you are up to it. Heavy is, above all, of course subjective. Dan Franklin's search for it is a personal one and that's what makes it so much fun. It's a quest that triggers one's own. In his search for what is heavy, Franklin crosses over from music to literature and film. Whereas Schopenhauer once said that you should be able to buy with a book the time to read it, with a book like HEAVY, which derives its reading power from a multitude of references that makes you Google while reading, you wish you could get that time as an infinitely extendible leporello. Reading HEAVY is like playing chess on several boards simultaneously with a recurring sense of shortcoming. (For why have I not yet seen Zabriskie Point by Michelangelo Antonioni?) Striking is the distinction Franklin makes in HEAVY between real heaviness and cosmetic heaviness. Nirvana is heavy, Limp Bizkit is not. The difference seems to speak for itself. The authenthic scream of Kurt Cobain that exorcises existential fears, as opposed to the band of Fred Durst who sees in their (derivative) nu-metal mainly an instrument for scoring girls (although a song like ‘Nookie’ comes from dealing with heart ache, the overcoming of the position of a underdog, its pose and triumphantness deprives it of any form of sympathy one might consider). After Nirvana crushed the plastic pop music and the glammetal of the 80's to pieces (eternal gratitude for that!) many a rockstar jumped on the bandwagon of the grunge. With grunge the focus turned inwards, rock music became more introverted. Grunge gave (hard)rock a new dark elan of heaviness (and Badmotorfinger of Soundgarden was the most heavy thing around; it was even more than Nirvana’s Nevermind, that had a remarkable universal appeal to the public at large, an album that separated heaviness from would-be heaviness). Instead of ‘just’ superficially chasing girls, the lyrics in grunge were about 'real' feelings. Many a glam rocker dressed up in a lumberjack blouse. Mike Tramp from White Lion turned to the 'dark' side (with Freak of Nature) and he wasn't the only one. Where in many a transformation from glam to grunge the commercial motifs were at display, the distinction between true heaviness and cosmetic heaviness (as a distinction between being sincere or not) was not always as obvious as first impressions suggest. Both Pantera and Alice in Chains had a hairmetal past and their exchange of hairspray for lumberjack check shirts might suggest, aside for creative motifs, a concern for the cosmetic (and commercial). Further on: WAGNERISM, what Mike Patton has in common with the French Symbolists and Wilhelm Furtwängler in Italy >> Who also had commercial motives when he composed one of the heaviest, most important operas in music history was Richard Wagner. Shy of money, as always, Wagner had an opera in mind that should be easy to produce. It turned out somewhat different for Tristan und Isolde. The line-up could be limited to two protagonists and a few supporting roles, the vocal demands, however, proved considerable. The potential places for the premiere, including Rio, Strasbourg, Paris and Vienna, all dropped out (70 rehearsals were needed in Vienna, but the singer for Tristan did not get his role learned). Not until 5 years after completing the opera the premiere took place in Munich (in 1865). Wagner initially had imagined Tristan for Paris, the cultural capital of the world, but after the disastrous performances of Tannhäuser in 1861 he abandoned that idea. He would no longer live to see his name established in the French City of Light, but his influence, posthumously, on French cultural life, especially literature, would become considerable. The French may not have loved him immediately, in the end they understood him like no other. The French Symbolists stretched their words where the music and libretti, their melody, timbre, color and rhythm, of Wagner had challenged them to. Mallarmé envisioned “a poetry that imitates music, surpasses it, and stages in the theater of the mind the higher drama that Wagner sought in vain.” It is one of the many examples in WAGNERISM; a marvel of a book in which Alex Ross explores Wagner's influence beyond the boundaries of music. What a text means and to what extend a text speaks are not the same thing. A meaningful text is something other than an expressive text. An intriguing part of the lyrics of Mike Patton (Faith No More, Mr. Bungle, Fantomas) is that the words are chosen for their sound as much, if not more, for their literal meaning. The words become, through their sound, an integral part of the music. It is not so much a text that is set to music, but setting sound itself. The message, eventually, is in the sound. According to Christiaan Thielemann that is one of the differences between Italian opera (in which words are set to music) and the German Wagner opera (in which Wagner is setting sound itself). Where for instance Verdi (and his librettist Boito) are cutting, distilling and dramatizing – Wagner is letting the sound flow. Back to that very first revelation in which I recognized in Wagner's music an old friend I had never known. In that music I recognised the classical music that my father used to play (Beethoven), but I heard that Wagner had modernised that music - stripped it of classical form - with an instant addictive effect. I couldn't explain it musically-theoretically, I didn't have to do so in order to surrender to it. It sounded like a confirmation of my inner self. A discovery of something that was not so much out there but a window I opened in myself. And it was as if Wagner made it clear to me that I could rely on my own feelings. That I could trust my instincts. A confirmation (if ever I needed one) that meant the world to me. Wagners' music was reminiscent of film music, it was music with great visual power. The first time I heard Die Walküre (a CD with a studio recording from 1962 led by Erich Leinsdorf with Birgit Nilsson and Jon Vickers) I didn't know what it was about, but a film passed me by. Later, when I checked in with the story and libretto, I didn't need a staging to imagine the story. When Wilhelm Furtwängler had completed the studio recording for EMI of Tristan und Isolde in 1952, he expressed the idea that Wagner's operas might thrive best in concert performances. He knew he was contradicting Wagner, but Furtwängler came to the conclusion that theatrical images only distracted audiences from the musical splendour and power in which, after all, everything was already incorporated. (Although that works differently for each individual. Director of The Last Jedi, Rian Johnson, told in a conversation with Alex Ross that Wagner's music only started to work for him after he had seen a Ring cycle in the theatre; he needed the images to comprehend the music). It was a long summer that now, with increasingly darker days, seems to have past so fast. I listened, for the first time in its entirely, to the RAI 1953 Ring under Furtwängler. I couldn't put my mind to it sooner, give it the attention it deserved. The RAI Ring is widely praised, it is Christiaan Thielemann's favourite Ring recording, but until now, despite the combination of Furtwängler and Wagner, it did not strike me as essential. The Ring that Furtwängler recorded in La Scala with Kirsten Flagstad as Brünnhilde was sufficient for me when it came to Furtwängler and the Ring cycle. Recorded live in 1950, this Ring has drama, theatre and depth. We experience a sultry winter storm with Günther Treptow & Hilde Konetzni as Siegmund & Sieglinde. Treptow is a powerful Siegmund who is not afraid to show his feelings - as befits a real man. The scene in which his Siegmund expresses to Brünnhilde that he prefers earthly love (in dire circumstances) with Sieglinde to a paradise life in the Walhalla cuts through the soul. Under Furtwängler's majestic handling of the large arches in the score flows smouldering magma. And Flagstad's Immolation scene makes me longing - despite a heartfelt ‘be careful what you wish for’ in these times of turmoil - for the end of the world. How Furtwängler heard and interpreted a composer remains an almost inexhaustible source of fascination. I am thinking of his performances of the symphonies of Brahms. Symphonies in which Furtwängler brings out an unprecedented energy and demonic power where, characteristic for him, especially in his live performances, he exchanges beauty of sound for romantic expression (probably not quite how Brahms himself must have had in mind). Musical phrases entrusted to gravity and time with a seemingly anarchistic slant. As if you push a container of boulders off the hill and, in the noise that follows, recognize a pattern that, as in a fractal, allows itself repeatingly to be dissected to a next level of smaller details. The result is breathtaking. It is Furtwängler who in no small way made Brahms and Tchaikovsy (his 1938 Pathetique!) accessible for me. Unfortunately, there is no Ring recording of him that in this way combines power, expression and drama (it remains to be hoped that a complete pre-Second World War Ring cycle recording from London will surface one day, it seems to exist).  The RAI Ring relates to the Scala Ring as a studio recording to a live recording. This Ring is recorded, one act at the time, for radio recordings with an audience that only reveils its presence by applauding at the end of each act. The RAI Ring is especially interesting for the singers. Compared to the Scala Ring, the RAI set-up gives them more space and they need less to compete with the orchestra. That orchestra sounds a bit stiff. Especially if you compare it to the Scala Ring and particularly if you put it next to the Ring that was recorded in Bayreuth that same year under Clemens Krauss. Furtwängler saw Hans Richter conducting Die Meistersinger in Bayreuth in 1912, and that performance stayed with him as his ideal opera performance. It was an opera like a conversation piece, a performance in which you forgot the music. Listening to the RAI Ring, you cannot escape the idea that Furtwängler extracts his own vision of the Ring, of Wagner, to a large extent from those performances under Richter, and successfully conveys that vison to orchestra and singers. Because of a struggling Italian orchestra, at times it is as they are still rehearsing the score, Furtwängler has to keep things audibly on track from time to time; it is indeed more of a conversation piece than hot-blooded drama. Eventually, the intoxication is no less; once descended into Nibelheim, it won't let go. Martha Mödl is a great involved Brünnhilde (she brings more drama to the role than Flagstad) and Ferdinand Frantz is a robust Wotan (he fits the Wotan that Furtwängler must have envisioned better than Hans Hotter, who was more lyrical). Julius Patzak's Mime, a key role in the whole drama, is a disappointment; he sounds more like an office clerk than an intriguer who tries to gain access to the Ring via Siegfried. Furtwängler came to Wagner a bit later in his professional life. As a teenager he thought of the Ring as just a superficial piece of musical theatre with an oversentimental libretto that lacked a heart, a human touch. It was an attitude that would change, but with Das Rheingold Furtwängler kept his reservations. He felt that this opera of the Ring was the most difficult to bring to life for the audience. In the RAI Rheingold these objections become tangible. The orchestra under Furtwängler rises a bit slow (literally) to the occassion and it is eventually not until Götterdämmerung that it blends in with the master's vision. But even then it doesn't really get to the underlying drama. We are never given a look at the primal forces that control the world. It is true that a fascinating story is being told here, with strings that turn to gods, man and fate with demonic pranks, but it remains a bit of a stiff excercise in which drama and expression remain stuck in a somewhat rigid presentation of music and text. It's a meal that at times is spicy but the salt and pepper in the playing of the orchestra never turns into musical umami. This Ring is an addition, no desert island stuff, but I'm glad it is there. Wilhelm Furtwängler may eventually have become affiliated with Richard Wagner, in name and fame, his favorite composer was Ludwig van Beethoven. The composer who, in 2020, thanks to that wretched bat from Wuhan, saw the festivities surrounding his 250th anniversary largely fall to dust. In the opening of the second part of his Seventh symphony (the Allegretto) Beethoven starts with an A minor chord. From there he goes to a combined E/G-major chord. Thus Beethoven says by musical means: "Happiness is there, where I am not". The Allegretto is melancholy in a majestic advancing chord progression. Resonation of the pace on which the mind seeks a place where relief and enlightenment can be found. At a time when we, even more than usual, have to depend on ourselves, the presence of good music, books and films is of more importance than ever. Extra thoughts and special thanks therefore to the writers and artists with which we (try to) make our way to the light at the end of the tunnel. The demands and expectations with which we burden their work may not always, especially now, be reasonable, but they stem from primarily felt needs: the need to enrich our inner self, to satisfy sincere curiosity and even to fight a deeply felt insecurity about our place in the world. It is all the more precious when music, books and films (art if you like) succeed in doing so and touches us where it enlightens the mind and gives us a glimpse of a world, deep within ourselves, that holds the promise and fulfillment to a better life.

- Wouter de Moor

And then you wake up in a world in which Eddie van Halen is no more. Like this year was not already strange and f*cked up enough. The fact that even musicians who, responsible for the soundtrack of your life, are bound to an appointment with the Grim Reaper, as if they were ordinary mortals, remains unabatedly disturbing. It plays one’s mind to no end, it makes one face the times beyond one’s own time, it makes one stop to function, not able to do the simplest of jobs. The death of a rock god lay bare that connection with music that is often more stronger, more intimate than the connections one has with spouses, friends and family. Because the music is always there. Unconditionally. It’s there for joy, sure, but it also keeps a mind in balance, it can be an invaluable partner that can get you through a difficult time. It triggers the imagination in unspeakable ways. Lost for words. Everything passes eventually but Music is so very present tense. And then being in a world where he is not in. Don't let the party antics of Van Halen's front men (Sam & Dave) fool you, Eddie van Halen's guitar tone was the heaviest thing in the known universe. (Play Romeo Delight and play the Annihilator cover from trash metal shredder Jeff Waters to prove a case in point). Pyro-technics, two-hand tapping and the trademark solos aside, the secret of EVH was in the rhythm, in the groove, in the heavy-metal-flamenco-style delivery of his licks. Never ‘just’ a barre chord or a mere repetition of riffs. Delivered with a right-hand attack, with his peculiar way to hold a pick, that burned strings and eardrums alike. (The quality of his rhythm work that, when Hagar became Van Halen's frontman and the songs more conventional, only got more prominent because Hagar "didn't want to sing over guitar solos". Bless Roth for songs like Hot For Teacher and As Is; riff clusters from which songs with lyrics are made. Chuck Berry on steroids. Pure gold because virtuosity is great but you carry it much better with you when you can sing along with it.) EVH was a musician that escaped the realm of the instrument he was playing (the notion that we lost the "Mozart of our times" is made more than once these days); he reimagined the electric guitar as a creator of sound. There is solace in good music, in inventive musicianship and EVH supplied that, in his own unique, idiosyncratic style, in large amounts. When I was young I wanted to be Him because for a child there is nothing more exiting than a big toy and in the hands of a rock god (how the hell is he doing that?), an electric guitar becomes the biggest toy of all - a magic wand with divine possibilities. Suffice to say that some dreams remain dreams. I often did not knew what I wanted in and from life but playing the air guitar? Always! Infinite pleasure in gesticulating, in dancing with your arms in thin air. Inexplicable freedom in expanding the mind with the idea that everything in life can be overcome, can be dealt with. Godly rewards from the fact that one can be, if only for the duration of a song or guitar solo, be bigger than life. We still have the music to revive dreams of old, as a gift for the ages, but His demise, like Neil Peart earlier this year, is hitting hard. Very hard. - Wouter de Moor