|

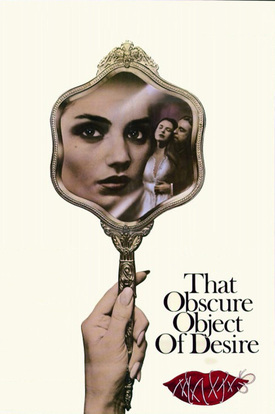

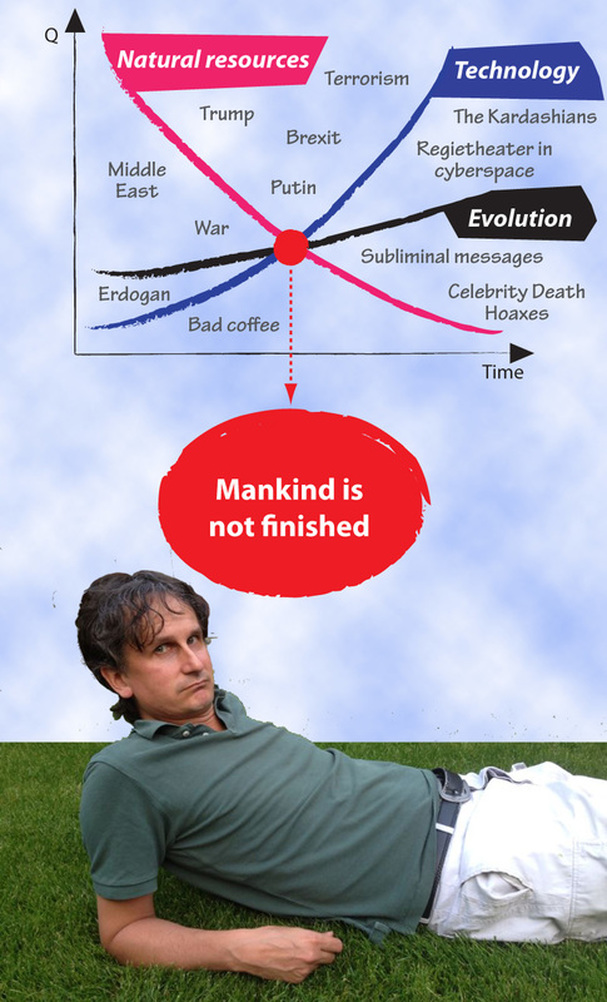

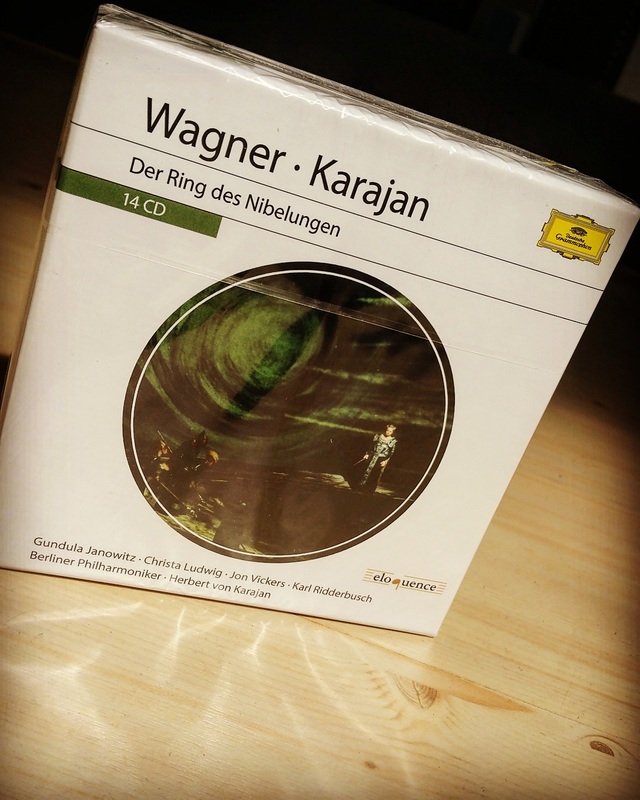

It's the best of times, it's the worst of times, it's the ... Well, at this point I don't know exactly what to make of it. I haven't put the news of the past few weeks in perspective yet. Time will tell what the future will have in store but I can't escape the feeling that we have entered a Luis Buñuel-movie. A world in which we can't tell parody from reality. I saw Buñuel's "Cet obscur objet du désir / That obscure object of desire" years ago and the movie surfaces because of its story and because of Wagner. At the end of the film loudspeakers announce that an alliance of extremist groups intends to sow chaos and confusion in society through terrorist attacks. The announcement adds that several right-wing groups plan to counter-attack. We see the main characters walking in a shopping mall in Paris when a bomb explodes, apparently claiming their lives. We are talking a movie from 1977. The scene reflects both Buñuel's past and present (Spanish civil war, World War II and terrorism – e.g. RAF, ETA & IRA - in the 70s). It can be also considered a forecasting of current events. A testimony that history doesn't necessarily repeat itself but surely, more than often, rhymes (thank you Mark Twain, for being such a quotable guy). Terror groups fighting each other for the right to commit terror attacks. The absurdity of that doesn't seem so absurd anymore. Living our lives, our love and lust, against the background of terror attacks, political and religious in nature. While listening to Wagner. It wasn't my idea. Buñuel went there first. In the last scene of “Cet obscur objet ...” we hear music from Die Walküre. The scene in which Sieglinde recognizes in Siegmund her long-lost brother. Earlier in the movie we are treated to Die Walküre's ouverture (nerd-info: it's the Böhm-Ring). It was not the first time Buñuel used Wagner's music. In his first two films (Un Chien Anadalou and l'Age d'Or - which he made in collaboration with Salvador Dali - he used music from Tristan und Isolde). Contemplating life, in the wake of the current state of affairs. The ears attuned to the beat of daily news - everything from the US presidential campaign till the next Celebrity Death Hoax (hello Jack Nicholson). The conclusion of it all can be no other than that mankind is not finished yet. We, as a species, are - as Carl Sagan has put it - in our puberty. And teenage angst and nuclear power make a dangerous combination indeed. Perhaps it is not until we have evolved into an life form without biomass, an intelligence without carnal lust and in no need of other physical needs, that we no longer run the risk of falling into the abyss of barbarism every now and then. We finally would be as Wagner sees his Parsifal. Someone who overcomes the world. Someone who can serve the world best because he doesn't need the world anymore. If only we don't annihilate ourselves first. Speaking of both Tristan and Parsifal. In spite of my intentions I'm not going to make it to Bayreuth this year. Plans to attend Parsifal and/or Tristan und Isolde were shelved with the failed attempts to get me a ticket (I'm still a few years short on the Bayreuther waiting list). But you don't need a ticket to have a video stream. It shed some light in my Wagner-loving life. Tweeting while watching Parsifal was perhaps not something Wagner intended but it made me feel, despite being outside the Festspielhaus, that I was part of a live audience. An audience in cyberspace was certainly something Wagner couldn't have envisioned but being the man who invented the invisible orchestra he would, perhaps, be kind to the idea of an invisible audience. People from all over the world who are able to witness his Bühnenweihfestspiel thanks to state-of-the-art technology (and Cosima doesn't have to worry anymore about Parsifal being performed outside Bayreuth, Bayreuth is coming to you). Missing my appointment with the Festspielhaus I am, like last year, bound to my own home theatre. A place where I, recently, added a new chapter to the Wagner experience. Last summer the Solti-Ring got a budget release and this year we have another cycle for budget price. A cycle that can be considered pivotal in the history of Wagner recordings: the Karajan-Ring. For this price a steal and impossible to resist. Quick after its release date I purchased a copy, before my friends could jump to the conclusion that I, finally, got me a life. Until the day that it becomes all clear that we were just missing Donald Trump's subliminal messages all along (It was all a joke folks!) I will have, with Karajan's Ring, the perfect summer drug. Submerging in beauty can be a tempting thing. In times of an unforeseen future (read: possible unnerving scenarios) even more than in days of wine and roses. Enter the Ring-cycle that Herbert von Karajan recorded between 1968 and 1970. Karajan, his approach more a concert performance than a staging of a music drama, delivers a gripping Ring. More gripping than I remember - from excerpts I heard on a CD with highlights and Das Rheingold (the first complete Wagner opera that came in my possession). Despite some objections I had beforehand (slow tempi and Karajan's iron grip on both singers and orchestra that prevents the drama to really unfold itself), this is a cycle I would rather not be without. Listening to it can perhaps be an indulging affair, a guilty pleasure it certainly is not. For that its qualities are undeniable. Karajan's quest for beauty Pierre Boulez found Karajan's chamber music approach a very important breach with the Wagnerian bombast of the past. It was an approach that acknowledged the importance of both detail in and audibility of the voices. The orchestra was there to lift up the voices, and not to fight them. The voices shouldn't struggle to overcome the orchestra. All of this, of course, envisioned by Wagner himself when he build his Festspielhaus. It was Karajan's disciplined orchestra, rich in detail and never overpowering the relatively small voices Karajan preferred to use, that Boulez marveled most. But Boulez' approach of Wagner was different than Karajan's. Boulez, with his superb sense of structure, didn't like to see Der Ring as a collection of leitmotifs. Emphasizing them would go at the expense of the impeccable architecture of Wagner's score. In comparison with Boulez Karajan is, in his unquenchable thirst for beauty, a bit like stating the obvious. He does not shy away from slower tempi and accentuating leitmotifs. Debussy, no member of the Wagner-fan club, acknowledged that there were some beautiful pieces of music to be found in Wagner's operas but that you have to wait for it so damn long. It's a bit like he's talking to Karajan. His Ring can be a trip from one highlight to the other, with interludes that add nothing significant to the narrative or overall structure. It was recorded round the same time that Solti finished his Ring cycle and I have to admit that I like Karajan a whole lot more. Solti serves the adrenalin and is the man for the special effects. He, undeliberately, shows that true drama can't exist without real beauty (his reading almost sounds like patchwork and he is pretty much a stranger to legato). In Karajan this is almost the other way around. Every “Oh” and “Ah” is sung with an obligation to beauty. Belcanto, pushed to the limits, even at the expense of drama and narrative. Against Wagner's own intentions who, when it came to singers, said that he preferred actors who could sing above singers who could act. In Die Walküre Gundula Janowitz sings, with a silver lining, an intoxicating and moving Sieglinde (her rendition of Strauss' Vier Letzte Lieder under Karajan was David Bowie's favorite birthday-present-to-give). But with beauty as a goal, almost in itself, her Sieglinde doesn't delve as deep as, for instance, Lotte Lehmann does for Bruno Walter (his first act Walküre from 1935 is da bomb). Jon Vickers is a heroic Siegmund and an exception to the rule that Karajan preferred small voices. Besides Vickers we have Jess Thomas (famous Lohengrin for Kempe) and whatever it is - Karajan's wish for intimacy that hits rock bottom here or Thomas being past his prime - his Siegfried disappoints. This Siegfried-Siegfried is too timid and, moreover, out-voiced by the Mime of Gerhald Stolze. The Götterdämmerung-Siegfried of Helge Brillioth is a lot better. There is beauty, also in the Fricka from Josephine Veasey. Even in places where her character (and the story) could use a jagged edge more than a clean cut. She would rather spend the rest of her days scrubbing floors than work for Karajan again. For her, the master of detail stepped across a few lines too many in his desire for perfection. The Wotan of Thomas Stewart wishes for Das Ende but how he gets there we don't feel. We hear the libretto leading him there but his treatment of the text lacks insight (it pales in comparison with Theo Adam's Wotan's second act monologue for Böhm).

Helga Dernesh is not the ideal Brünnhilde. I made acquaintance with her in Karajan's studio Tristan (also with Vickers) and her Isolde lacked warmth and compassion (you needed a lot of love potion to fall for her). She fares a lot better here than on that recording but she comes nowhere near the pantheon of great Brünnhildes where Nilsson, Varnay and Leider dwell. Not that it matter much. We can have an entertaining football match whilst not having Messi and/or Ibrahimovic on the pitch. When Dernesh finally gives back the damned ring to the Rheinmädchen and Valhalla is burning, we are not burning ourselves on the flames. The world, even on the verge of perishing, is having an obligation with beauty more than it's bothering about its own non-existing. Perhaps this is Wagner in a nutshell. We're doomed and we don't care because damnation never felt so good. The world is ending and it sounds more beautiful than we could have imagined (and the only thing you need for a convincing staging is smoke). "Erzählen und nicht zelebrieren." It is, in short, Hartmut Haenchen's approach for Parsifal. From Karajan can be said that he has a taste for “zelebrieren”. Having his career started in Austria and Germany between two world wars. His role, before and during the second one, controversial almost until his death, Karajan has wanted - with his ideas about music in an ideal sound – to make a pledge for the beauty and the vulnerability in man. It lifts this Ring far above average while it keeps, at the same time, the human aspects of Wagner's music drama in a blister. We can have a story with Gods, giants, Nibelungen and Walsungen, the motivations and emotions of the characters are, of course, purely human. In one's search for the ideal Ring one balances the pros en cons. And after more than three Ring recordings one gives up the idea that there is such a thing as one Ring that rules them all. The next logical step is to become a Ring-collector and value each recording on its own merits. And find out that the one Ring that rules them all is in your head. And in your head only. Krauss reminds me of its humanity, Böhm of its drama, Karajan of its beauty, Boulez of its modernity and superb architecture, and Solti how to annoy the neighbours. The one true Ring is a work of progress. Shaped by countless hours of listening to a lot of different recordings and by attending several live-performances. The merger out of that. That's the one Ring you ultimately live with.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

TIMELINE

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed