WODE is born in the post-industrial gloom of Manchester, UK. A Black Metal Quartet that with each release shows itself curious in exploring new territory. WAGNER & HEAVY METAL asked singer & multi-instrumentalist MICHAEL CZERWONIUK about the band's influences and sources of inspiration. 1. How aware are you of your influences when you write? Difficult to say. A song will typically start with one of us coming up with a riff at home, which may have been influenced by something we were listening to or just through playing around on guitar. Once the riff or fragment is brought to the rehearsal room it will go through various changes and new sections will be written on the fly. Sometimes these sections will be labelled ‘the x-band riff’ if there’s some similarity to another band and for ease of communication, but any similarity will usually become apparent a bit later on. The music, particularly with the new album, passes through a lot of different styles (black metal, death metal, heavy metal, punk, doom metal) partly because we want a song to take many unexpected turns and also just because that’s the kind of music we’re into. I think the care we take when arranging makes the music sound cohesive despite being so varied, and the band’s personality makes the music sound like its own thing rather than a sum of its parts. 2. Burn In Many Mirrors means again that the band has expanded its sound compared to its predecessor(s). Is every new record a conscious exploration of new territory? Do you think it's important not to repeat things? How do you see the development of the band's music? We try not to repeat ourselves too much and tend to view each album as a separate statement but we don’t have a preconceived notion of how an album will sound before we start writing. Once we’d written the first song for the album (Sulphuric Glow) it became apparent that we were tapping into something that felt new to us, more dramatic and with a lot of different elements. But again, that exploration was quite an organic thing, aided by a few beers and the enjoyment of following a song down the rabbit hole rather than writing with some grand plan in mind. Of course some elements from the previous albums are going to be present either intentionally or subconsciously, simply because it’s mostly the same people writing the music, but generally we are always trying to push things into different territory. 3. Does each band member bring their own specific influences or are all the band members into the exact same music? We’re not all into the exact same music but our tastes tend to align when it comes to the fundamental music that the band draws from. We all contribute riffs and sections when we write together and each of us has a different way of writing and type of riff that we tend to come up with, which is what makes the music quite diverse. 4. Beside influences inside metal (Judas Priest etc.), do you have any influences outside metal? The music we write is fairly oblique in nature so we’re open to inspiration from a wide range of sources outside of metal as long as it fits the right kind of mood. For example, the nihilistic heaviness of a band like Swans in their early days, the raw power(!) of the Stooges, darker 80s punk/post-punk like Amebix, Die Kreuzen, Christian Death, Killing Joke, the atmosphere and synthetic elements of groups like Coil, Dead Can Dance and Popol Vuh all feed into what we’re doing in some way. 5. How do you rate the importance of the lyrics? What inspires the band the most when it comes to writing lyrics? Lyrics and themes are very important in building a world which an album inhabits. Much like the music, lyrical inspiration comes from a lot of different sources. Our environment - the post-industrial gloom of Manchester - is a constant source of inspiration, films, conversations, dreams, folklore and mythology, writers like William Blake, Arthur Machen and Robert Macfarlane are all points of reference for the new record. As important as the lyrics are, the vocal delivery and phrasing is just as important. I’ll always favour a lyric that sounds good amongst the music rather than trying to shoehorn in something that reads well but doesn’t necessarily fit the structure. 6. Final question: does the band have any specific goals in mind (besides world domination)? Right from the start the goal has only ever been to write the kind of music that we’re proud of and would want to listen to. Any praise or tours that come along with that are obviously a bonus but the main thing is that we continue to be excited by what we’re doing. - Wouter de Moor

0 Comments

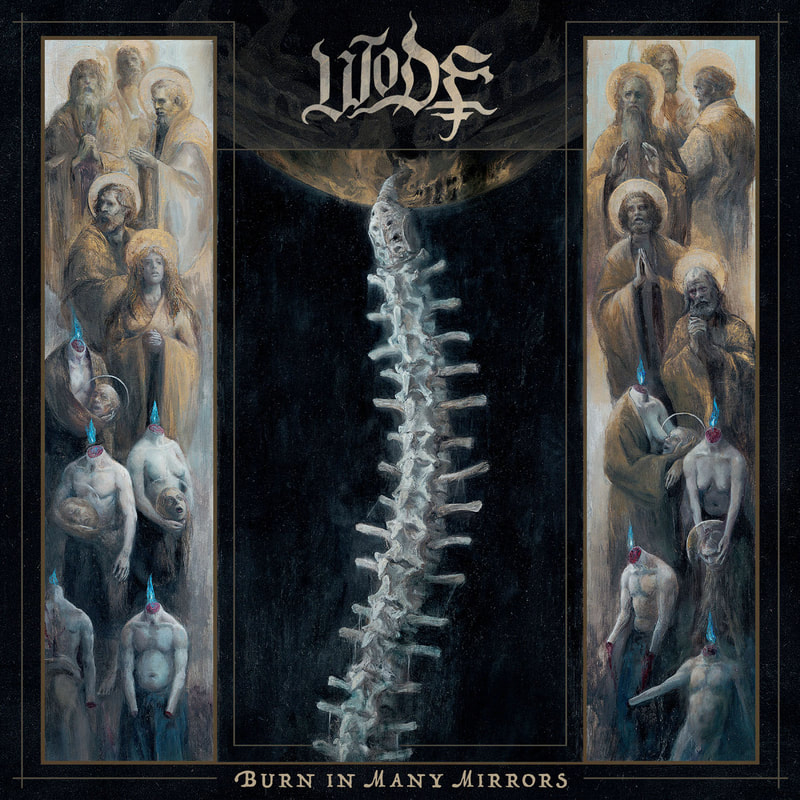

Looking for the sounds that seek the mystery in the mundane. Wandering around where an unknown master of the senses, far away from everyday worries, pulls the strings. Music for those who are not satisfied with this world, who want to cross over to that area beyond consciousness where fear and desire can roam free. The art that takes you away from the all too crushing normality of things comes in many forms, and heavy metal is one of them. Of all the styles in metal, black metal is probably the most romantic one, and the sub-genre that is already so generous with great releases, once again delivers a marvel of a record. Their first record was one of scorching and intoxicating black metal. On their second record they sharpened their riffs to more punchy songs and now there is a third record, BURN IN MANY MIRRORS, with which WODE expands their sound further. BURN IN MANY MIRRORS is a black metal record with a death metal flavour that also feeds on classical metal (Judas Priest, New Wave of British Heavy Metal etc.) and is not unaffected by the atmosphere-enhancing sound-expansions of prog rock (we will continue to call the music, in a genre that seems to create a new sub-genre with the release of every new record, Black Metal). By adding extra layers to their sound, WODE has taken another step forward, stretching the boundaries of black metal (the genre that possesses hallucinatory qualities like few others) and pushing themselves to further explore a musical landscape in which demonic realms and punkish energy refresh the mind, and blow the inertia that thrives so well in Covid times out of the window. (Introverts thrive with Metal. And Metal thrives in lockdown it seems, if you look at the many, good releases of last year.) The pandemic threw sand in the machine of a lot of things a year ago and WODE have used the extra time Covid created in their agenda to give some extra attention to the synth parts for their new album. It's very nice to see the prog rock influences adding to the atmosphere and substance of WODE's black metal without sacrificing the all-encompassing, hallucinatory power with which the black metal of their debut impressed so much. The synth parts form an organic whole with the undead glory of guitar parts that sail like surf riffs on distortion over pitch-black waves. Michael Czerwoniuk's vocals are like the scream of an obscure, half forgotten god who, together with the instrumentarium, paints a multicoloured greyish sound spectrum in which the melody is interwoven throughout the music. In full awareness that life can only be captured and understood with poetic dedication, one embarks on a quest with musical means that leads to a place where the boundary between dream and reality fades away. With songs that engrave themselves in memory, one crosses over to that part of the mind where, free from gravity and time, liberation and redemption can be found. The infinite journey to liberation, starting point for so much beautiful art, is evocatively started here with Lunar Madness, a howling at the moon in which the intro establishes a perfect, organic connection with the all-crushing madness that follows, an incredible album opener. WODE does not waste any time after that, intros are atmospheric but do not detain (a small reservation can be made for the intro of the album closing track Streams Of Rapture that lasts almost 2 minutes) and rounds off BURN IN MANY MIRRORS in about 40 minutes (the playing time of a vinyl record, an invitation to put it on repeat). BURN IN MANY MIRRORS extracts a theatre of the mind from a swamp of dark sounds, a realm of images brewed by sulphur vapours in which the delirium tremens of blackened metal casts its own intoxicated gaze at the world. You can face life with renewed energy when the 40 minutes of BURN IN MANY MIRRORS are over. A record with which WODE, with a demonic sense of decorum, settles down in the vanguard of the present-day metal scene. LINE-UP: M. Czerwoniuk - Vocals, Guitar, Synth & Keys D. Shaw - Guitar & Backing Vocals T. Horrocks - Drums, Guitar, Synth & Keys E. Troup - Bass Guitar - Wouter de Moor

Black metal from Dutch soil. Elfsgedroch stirs in a mythical soup and serves, with hallucinatory flavors, a luscious metal meal. After “Op De Beenderen Van Onze Voorvaderen”, “Dwalend Bij Nacht en Ontij” there is “Gedoemd tot de Eeuwige Jacht” (Doomed to the Eternal Hunt). "Elfsgedroch" is a term that dates back to the 12th / 13th century, to Marlaent's "Spiegel Historiael" and the medieval poem "Karel ende Elegast" in which "Elfsgedroch" is described as the work of fallen angels who, as the devil’s kin, descend to do their stinking work on earth. Elfsgedroch, the music, is, by analogy with more recent mythology, Tolkien on steroids. Fantasy in overdrive with a grunt from the underground. What if Sauron had a guitar and gave voice to his inner turmoil? Elfsgedroch, the band, stain their songs with blood and mud. With Elfsgedroch, the beast with blackened heart comes with many names - from Boezenhappert, Okkerman to Waternekker.

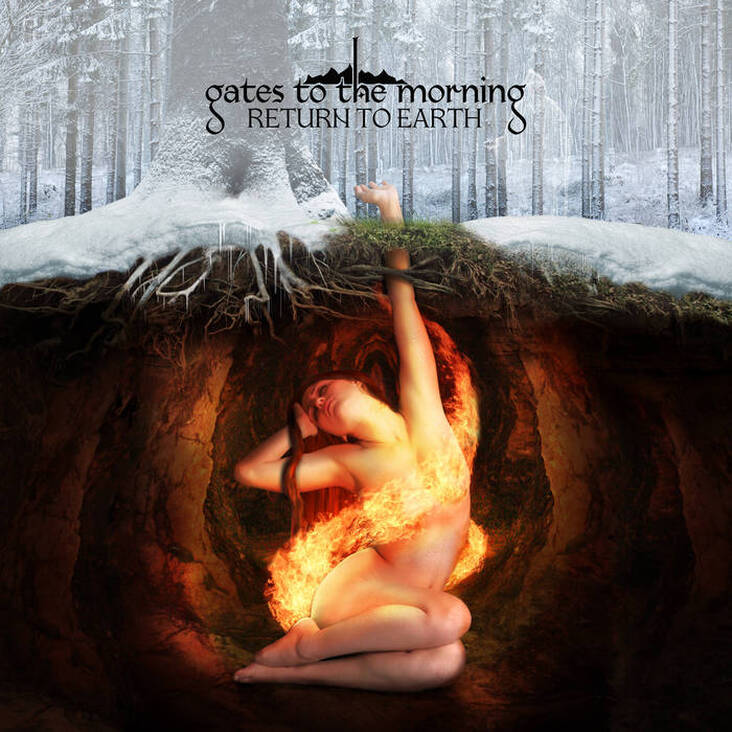

The grunt comes as the roar of the siren, buried deep into buzzing guitars and rolling drums, irresistibly resounding in the distance. It stretches the voice to the edge of audibility, giving it a meaning beyond words. Music as a landscape that reports of a journey that both purifies and alienates. With that rare quality to bring out opposites together in a non-conflicting way, the music is robust yet swift, dark yet full of life. With grand gestures, free from formulaic constraints, it leads you away from the daily craze- extra appreciated in quarantine times. These are soundscapes in the best sense of the word. Here what is served makes you hungry for more. “Gedoemd tot de Eeuwige Jacht” is a black metal mass, decorated with mythological aesthetics, that testifies to a deeply romantic longing for meaning and something beautiful in a disenchanted world. A listening experience in which, to paraphase Novalis, the banal becomes exalted, the ordinary mysterious and finiteness is given the guise of infinity. Listen! With Return To Earth, Gates to the Morning releases its debut album Gates to the Morning is a band project that originated in the bedroom of Sean Meyers. With the debut album, Return To Earth, Meyers now set sail for the whole wide world with a wide range of styles in his backpack. He started out as a jazz musician - his influences range from Art Blakey to bands like Opeth and Tool - and he labels the music of Gates to the Morning as Post Black Metal. Return To Earth is an invitation, especially for those listeners who want their music spiced with strong theatrical and storytelling elements. A listener, with a predeliction for concept albums, that likes to take, in the etheral atmospheres of a panoramic musical landscape, a mind trip. On Return to Earth you can hear the love for fantasy, for Tolkien, the love for grand gestures. Return to Earth takes one on a journey of life; an encounter with many challenges, inevitable disappointments and victories. A musical journey, Mahlerian in ambition, that eventually leads to self-realization and enlightenment. For what the genre-name Post Black Metal is worth: Return To Earth is a record that surely will appeal to the lover of symphonic rock. The album provides mood-creating soundscapes that are broken open by changes in tempo and atmosphere. A carefully prepared musical meal, a skillfully built theater of kaleidoscopic sounds in which Sean Meyers gets help from studio engineer Kevin Antreassian (The Dillinger Escape Plan). Return to Earth is an exciting musical enterprise that doesn’t go where nobody went before but where its creator succeeds in making his personal and musical interests and preoccupations palpable for the listener. Towards the end of the album, that journey loses some of its momentum and its excitement. Atmosphere goes at the expense of musical substance and variety. Here some more "Art Blakey" instead of "late period-Opeth" would have kept the tension arc better. Album closer is the title track, beautifully sung by Meg Moyer, with which this journey, the accomplishment of what once started in the intimate environment of a bedroom, ends in a great and magnificent way. Happiness & joy because PANDEMMY releases new material and the Brazilian metal band again does not disappoint. After the fantastic "Rise Of A New Strike" from 2016 comes Obliteration, a split-record with Italian metal band ABSCENDENT. The opening Monstera may sound a bit like an atmospheric warming-up with a not too strong musical aftertaste, the follow-up, however, is ear-shattering. In the music of PANDEMMY a lot happens; the grunt is deeply buried in the music but the relative lack of melody in that department is sublime complemented by the instruments; the inventive melody lines coming from the guitars (shredding as if they play their own metal variations of Flight of the Humble Bee) fill in an important part of the songs and the shifting time signatures are breathtaking. PANDEMMY is total music in which the several influences are not too difficult to trace (from Carcass to Megadeth, see also this interview with the band), but these are absorbed in one organic whole in which the sum is many times greater than the parts. Four new songs and a Motörhead cover (Them Not Me from 90s album Overnight Sensation thrown in the trash metal shredder) are PANDEMMY’s contribution to Obliteration and in those songs happens more than on many other bands' full albums. PANDEMMY condenses their ideas into bold, catchy songs that can best be described as mind-expanding knuckle sandwiches. Just like with "Rise ..." the songs (and yes, it's a pity they're no more of them) ultimately string together as movements in a metal symphony. In the same ultra-heavy niche as PANDEMMY we have ABSCENDENT. The Italians stay more at the trashy side of things than their Brazilian colleagues, their metal sounds a bit less hallucinatory, but also their songs kick frantically ass. They also bring four own songs to the show where the final cover -Spirit Crusher of death-metal legends Death- can be considered as an ultimate prove of metal competence. On Obliteration death breathes life. It energizes and makes one attack the day like a bird of prey. A mind blowing metal heist.  DIABOLOGY are a teenage thrash metal band from Los Angeles, CA. Members Jesse Bergen (guitar and vocals), Jack Kleinman (guitar), Aiden Wogh (bass) and Matthew Morales (drums), met up on the rock school circuit. They were united by a love of metal and a desire to break out of the rock school mold to start working on original material. Defying the many subgenres of metal, they choose to simply call their music thrash, a tribute to the old school sounds of the late eighties, with a young and refreshing voice. Check out their music in the links below. From the epic Seas of Eternity, a sledgehammer of a tribute to the death metal legends of Deicide to a moving, and hilarious, About You (metal hugs are the best!) With a nu-metal after taste, with echoes of Korn and Helmet, comes the music of SALEM TRAILS. They sound fresh -don’t let the references to the aforementioned bands that have their base in the 1990s make you think otherwise- and kick serious ass, both music and lyric wise. The lyrics of their new single Rotten Path, address depression, regret and suicide. The band is committed to donate sales from this single to Kids Help Phone. Rotten Path is up for purchase on iTunes and Band Camp. From Wales comes Paraskenia. A metal band that released with "When Darkness Falls" their debut single. An interview with singer Lee David Bowen who likes to traverse the worlds of opera, musical and metal. Now you sing with Paraskenia next to opera/classical repertoire (and musical) also metal. What was there first: your interest in opera/classical music or your interest in pop/hardrock/metal? As a teenager I was a massive metal fan and loved anything to do with Iron Maiden. My favourite albums being Powerslave, Iron Maiden [their self titled debut] and Killers. Halloween's Keeper of the Severn Keys Part one & two were also favourites of mine for the drama and storytelling. I was lucky enough to see both these bands live during the 80's and 90's. Growing up in Wales, "The Land of Song", I was also introduced to classical music at a young age and the first opera I saw was WNO's production of Tosca with its powerful opening had me hooked. What are the technical differences for you between singing opera and metal? The style of Paraskenia's music allows me to sing in the same way for both metal and opera. I believe that good technique and building stamina are integral in both styles. Having worked as a principal in the West End in The Phantom of the Opera. where we performed 8 shows a week and with many major Opera companies in the UK, I believe I have a good stamina so I'm not pushing my voice. Do you need to take special care when singing metal (with amplified instruments). Do you (have to) take special measures to protect your voice? It's all about good technique and not pushing the voice. Also the other members of Paraskenia are knowledgeable musicians and understand the nature of both classical and metal singing. Gareth Long on keyboards is an operatic bass (touring with Scottish opera at the moment). Before any performance whether classical or metal I try to get plenty of rest and avoid alcohol. I also find meditation and yoga really beneficial. 4. There is perhaps a tendency to held pop/rock music, from an artistic point of view, in less higher esteem than opera/classical music. How does that work for you? How do you value both? And do you encounter any prejudices against pop/rockmusic in your own classical music environment? I haven't really come across much prejudice in the classical music world and generally find that most musicians appreciate all good quality music even if its not to their particular taste. 5. What are your favorite singers? (Any genre possible.) Bruce Dickenson (Iron Maiden), Siegfried Jerusalem, Simon O'Neil, Sir Bryn Terfel and Stuart Burrows. Paraskenia:

Lee Bowen – Vocals Gareth Long – Keyboards Andy Slade – Lead Guitar Richard Emanuel – Rhythm Guitar Ben Thomas – Bass Guitar Ceiran Jenkins – Drums With the release of ALIF, Algerian band LELAHELL delivered a knuckle sandwich of a death metal album that takes the listener by desert storm. Wagner & Heavy Metal spoke with frontman and founder of the band, Redouane Aouameur. . What is the story (if there is one) behind the name Lelahell?

Lelahel (with one 'l' letter in the end) is an angel of the zodiac exercising dominion over love, art, science and fortune. We appeal to this being of light for good luck and good fortune. We added an 'l' because there is already an Italian rock band named Lelahel, and Lelahel is also my nickname so to make a difference between them I added a second 'l' in the end of Lelahel. 2. On both your albums you are telling the story of Abderrahmane. What lies at the root of this character? (e.g. religion, mythology, folk stories, real life events etc.) Each Lelahell release is conceptually linked to the character of Abderrahmane, yet focusing on another evolutionary step—another chapter in his own book. In the lyrics of our first EP "Al Intihar" Abderrahmane is tired of his own life full of constraints, so he commits suicide. Our first album "Al Insane... the (Re)Birth of Aberrahmane" deals with his rebirth. Our new album "Alif" is now focusing on Abderrahmane's first steps in his new life, just like a child learning to speak, walk, learning about the world around him. Yet this is full of foes and fears, that's why Abderrahmane needs to save himself from those dangers. The root of that character is a pure fiction! 3. Is there a special reason why you choose to write your lyrics from the perspective of Abderrahmane? (What inspires the band the most when it comes to writing lyrics?) Abderrahmane is the name of my father (R.I.P) and my son. When it comes to writing lyrics we get our inspiration from our past experience, our daily life and everything around us (nature, society …) 4. What are your main motivations to play this kind of music (death metal)? The main motivation is we like that sound, we like the sound of the guitars, we like the fast rhythms and the guttural vocals! 5. What musician / bands made you wanted to play music yourself? What bands are of the biggest influence on your music? The biggest influence is the old school death metal scene with bands such as: Morbid Angel, Cannibal Corpse, Deicide, Death and more … 6. Is there a metal scene in Algeria? And if so, what is it alike? (Does is know subgenres? If so, which of the subgenres are most popular?) The metal scene in Algeria isn’t as new as people imagine, it exists since almost 3 decades. I’m one of the formers of that scene, and one of the last active survivors! When we started in the early 90’s it was really difficult because we were the firsts, there was no models to follow, no experienced musicians to ask, no references, but we were very ambitious and motivated . Some years after in the mid 90’s it was the golden era of the Algerian Metal, a lot of bands were formed, a lot of people in the concerts, full support from government, … But 10 years later a lot of commercial musical styles appeared in Algeria, and the authorities were not supporting that music anymore because it was something ‘non’ conventional and ‘occidental’ so it was really difficult to find venues for that music and a lot of musicians have stopped playing because they approached the 30’s and preferred to focus on their life (job, marriage,…). In 2018, things have changed. There are some new promising bands that were formed and have made some interesting releases, there are also more concerts but not enough, we are trying to change things with government to get more access to the venues, and why not create a big international festival! The most popular subgenre in Heavy Metal are Death Metal and Thrash Metal. 7. What is the writing dynamic among members of the band (does only one person write the songs or is song writing more a band effort)? Does each band member bring their own specific influences or are all the band members into the exact same music? I’m the only one who writes the music and lyrics. The band started first as a one man band, it is the right method since the begining of Lelahell, and maybe it will change for the future. 8. Lelahell's music has influences of Algerian folk music. Does the band (its members) have more influences outside metal? We all listen to different music than metal, but we don’t use it in the music of Lelahell, we just add some folk scales and rhythms! 9. How do you see your own musical development? Are there musical areas that you still want to explore? For the future we will focus more on the music itself, I mean the arrangements and the interaction between the instruments. We will add new sounds to the music of Lelahell. Stay in touch and you will see! 10. Do you believe that music (and heavy metal in particular) can be more than just entertainment? Can it be a force that can change things for the good on a larger scale? (Music as a mean that can raise awareness about, for instance, political and environmental issues.) There are many people that consider it as more than an entertainment; it is a way of life in certain regions like Finland, Norway or Sweden. Bonus question: do you have any specific goals in mind for the band (besides world domination of course)? Our main goal is to create something in the music that people will remember it for a long time, for example a new sound or maybe a different way to play the music, or a new concept, or I don’t know something different. From Algeria comes LELAHELL, death metal that takes your eardrums by desert storm LELAHELL's latest output, ALIF, is a follow-up to their debut All Insane ... The (re)birth of Abderrahmane. ALIF tells the story, in music and lyrics (in English, French and Arabic), of Abderrahmane. A man who takes his first steps in his new life, like a child that has to learn to speak (again), to walk and has to learn about the world around him. A world that harbours many dangers. With PARAMNESIA the album opens in kick-start mode and takes the listener from there. Caught in a desert storm of fiery riffs, with references in rhythm and melody, to Algerian folk music, the death metal of the Algerian combo massages the ears and cleanses, like good metal should, the soul from everyday's weariness. If the music on ALIF gives us any indication of the way Abderrahmane deals with the dangers he encounters we can consider the third track of the album, the contemplative instrumental THOU SHALT NOT KILL, an aural depiction of a resolution made in vain. ALIF contains aggressive and violent music, packed in tight instrumentation. The folkore references (e.g. the intro of INSIRAF / MARTYR) bring colour in a musical world of black and grey and are used freely and thoughtfully. The result is always organic and adds significantly to the energy of the music. This is heavy metal world music, one cannot help thinking of Max Cavalera's Soulfly, that leaves an ironclad groove in your brain every time you listen to it. And although the vocals stick to a staccato / hardcore grunt most of the time, the music contains a rich array of melody. ALIF is knuckle sandwich death metal that comes with a lot of atmosphere. When we arrive at the last track, the instrumental IMPUNITY OF THE MUTANTS, we await a album-closener that sounds like an accumulation of everything that has passed us by in the nine previous tracks. It leaves us with the feeling (whether we were able to follow the lyrics or not) that we have been through a lot. That we've witnessed a story that came with an urge - as if it fought its way out to the world. A story that is not only most pleasant to listen to but that is also worth telling.

LELAHELL: RECORDING LINE UP for ALIF : Redouane Aouameur : Guitars/Bass and Vocals Hannes Grosmann : (ex-Necrophagist ex-Obscura, Alkaloid, Blotted Science): Drums ACTUAL LINE UP: Redouane Aouameur : Guitars and Vocals Ramzi Curse : Bass Slave Blaster: Drums ALIF by LELAHELL on Bandcamp >> Interview with Redouane Aouameur >> |

Archives

April 2021

BANDS & Musicians

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed