|

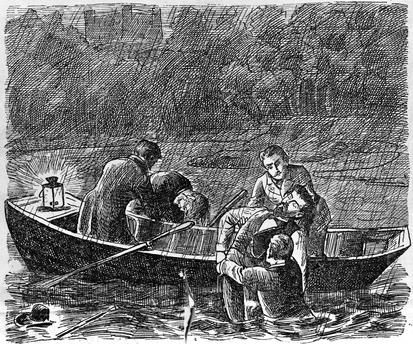

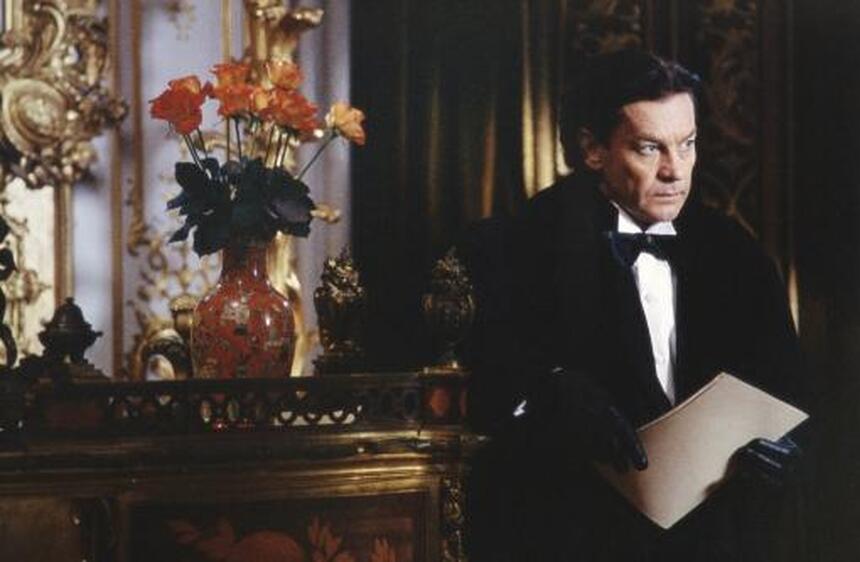

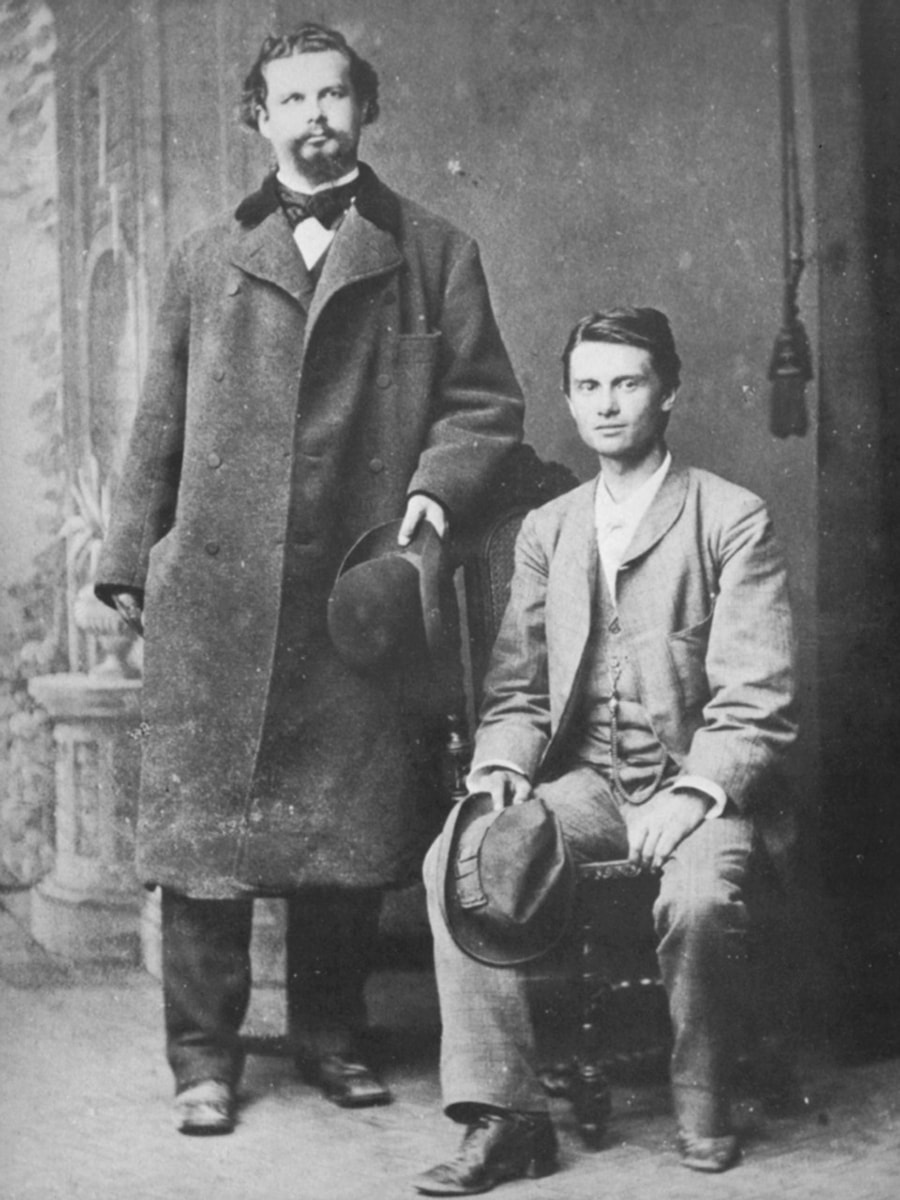

On June 13, 1886, Ludwig II, king of Bavaria, was found dead in Lake Starnberg near Berg Castle. He was 40 years old. The circumstances surrounding Ludwig II's death remain enigmatic to this day. Officially, his death was labeled a drowning (after Ludwig allegedly killed his doctor), but there is at least one witness who stated that there may have been murder, a staged death. With his flamboyant, megalomaniacal personality and his grand palaces for which he relied more on stage designers than architects, Ludwig continues to fascinate to this day. A man with an unconventional mind, a king who cared little or not for affairs of state. A man for whom art was not a luxury but a necessity of life and who enabled Richard Wagner, through generous donations, to complete his Ring des Nibelungen and build the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth (for which eternal thanks) In addition to his castles that attract many tourists each year (Sloss Neuschwanstein, the largest castle, was opened to visitors just seven weeks after Ludwig's death), Ludwig lives on in films, the most famous being those with Helmut Berger. Berger's role as the Fairy Tale King in Visconti's Ludwig II is perhaps his best. With Berger's portrayal, the development from sensitive young man to paranoid, alienated from everyone is a poignant, compelling watch and an artistic highlight for the actor. That other film in which Helmut Berger takes on the role of the King of Bavaria, Ludwig 1881, tells the story of Ludwig instructing an actor, Josef Kainz, to go on a trip with him in which Kainz must recite scenes from Schiller's Wilhelm Tell on location. In this traveling private theater, Kainz is for Ludwig besides a man who embodies beauty and art, perhaps even a desired friend, the link between Ludwig and the outside world. "Tell me what you see outside," Ludwig asks Kainz as they sit on a boat, the curtains closed. "Why don't you have the curtains opened then you can see for yourself," the actor replies. Ludwig does not want to see nature himself; he wants to know how an artist sees nature. He considers that more genuine. The actor who tells Ludwig what he sees when he looks outside is the link between man and nature. (Anticipating Mahler who once said to his visitor in the Austrian Alps, "You don't have to look outside, I have captured it in my symphony."). Nature is capricious and indifferent to man. With the image by which it is described, captured, nature is stripped of its whimsicality. By controlling nature, it is completely at the service of man. When Ludwig looks into a slide viewer at images of the entire world, from Africa to Asia, he comes to the conclusion that he no longer needs to travel. He can stay home from now on and he will. The trip with Josef Kainz would be the last one he would undertake. He would continue to shut himself up in his castles and, above all, in his own head. Ludwig is a man of privilege. Everyone around him is at his disposal. He is, like a collector, always looking for those stimuli that please and move him. He makes himself increasingly unfit for life, for the outside world. He is spoiled but the development of media, since the late nineteenth century, has now made us all kings in our own kingdom. Ludwig's legacy endures not only in the stone edifices that draw crowds, but in the echoes of his sequestered soul, mirroring our own entrapment within the all-encompassing dominion of screens. As we navigate our augmented and alternative realms, we, too, become modern-day monarchs, ensnared in our palaces of pixels and code. - Wouter de Moor

1 Comment

|

Archives

September 2023

Name/dropping

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed