|

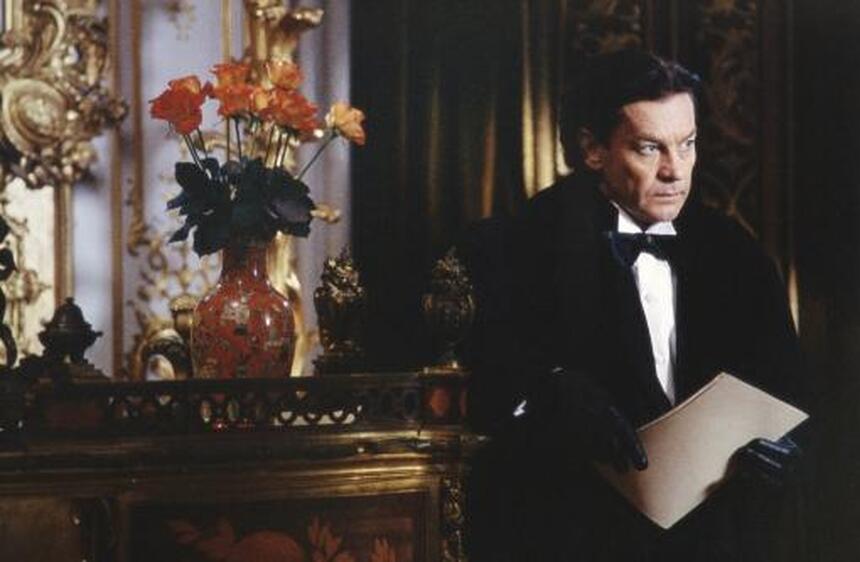

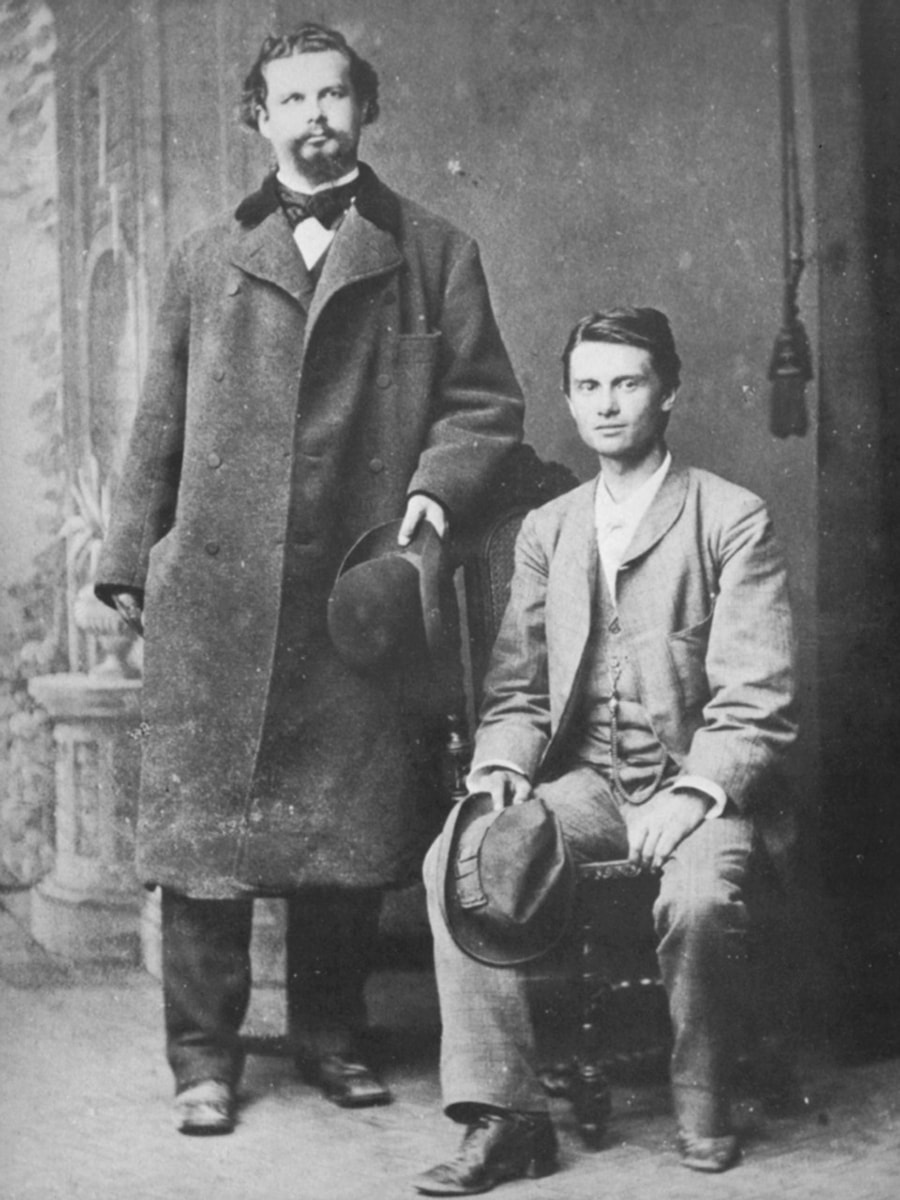

On June 13, 1886, Ludwig II, king of Bavaria, was found dead in Lake Starnberg near Berg Castle. He was 40 years old. The circumstances surrounding Ludwig II's death remain enigmatic to this day. Officially, his death was labeled a drowning (after Ludwig allegedly killed his doctor), but there is at least one witness who stated that there may have been murder, a staged death. With his flamboyant, megalomaniacal personality and his grand palaces for which he relied more on stage designers than architects, Ludwig continues to fascinate to this day. A man with an unconventional mind, a king who cared little or not for affairs of state. A man for whom art was not a luxury but a necessity of life and who enabled Richard Wagner, through generous donations, to complete his Ring des Nibelungen and build the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth (for which eternal thanks) In addition to his castles that attract many tourists each year (Sloss Neuschwanstein, the largest castle, was opened to visitors just seven weeks after Ludwig's death), Ludwig lives on in films, the most famous being those with Helmut Berger. Berger's role as the Fairy Tale King in Visconti's Ludwig II is perhaps his best. With Berger's portrayal, the development from sensitive young man to paranoid, alienated from everyone is a poignant, compelling watch and an artistic highlight for the actor. That other film in which Helmut Berger takes on the role of the King of Bavaria, Ludwig 1881, tells the story of Ludwig instructing an actor, Josef Kainz, to go on a trip with him in which Kainz must recite scenes from Schiller's Wilhelm Tell on location. In this traveling private theater, Kainz is for Ludwig besides a man who embodies beauty and art, perhaps even a desired friend, the link between Ludwig and the outside world. "Tell me what you see outside," Ludwig asks Kainz as they sit on a boat, the curtains closed. "Why don't you have the curtains opened then you can see for yourself," the actor replies. Ludwig does not want to see nature himself; he wants to know how an artist sees nature. He considers that more genuine. The actor who tells Ludwig what he sees when he looks outside is the link between man and nature. (Anticipating Mahler who once said to his visitor in the Austrian Alps, "You don't have to look outside, I have captured it in my symphony."). Nature is capricious and indifferent to man. With the image by which it is described, captured, nature is stripped of its whimsicality. By controlling nature, it is completely at the service of man. When Ludwig looks into a slide viewer at images of the entire world, from Africa to Asia, he comes to the conclusion that he no longer needs to travel. He can stay home from now on and he will. The trip with Josef Kainz would be the last one he would undertake. He would continue to shut himself up in his castles and, above all, in his own head. Ludwig is a man of privilege. Everyone around him is at his disposal. He is, like a collector, always looking for those stimuli that please and move him. He makes himself increasingly unfit for life, for the outside world. He is spoiled but the development of media, since the late nineteenth century, has now made us all kings in our own kingdom. Ludwig's legacy endures not only in the stone edifices that draw crowds, but in the echoes of his sequestered soul, mirroring our own entrapment within the all-encompassing dominion of screens. As we navigate our augmented and alternative realms, we, too, become modern-day monarchs, ensnared in our palaces of pixels and code. - Wouter de Moor

1 Comment

"On Christmas Day, my 31st birthday, this notebook was to have started; I could not get it in Lucerne. And so the first day of the year will also contain the beginning of my reports to you, my children. You shall know every hour of my life, so that one day you will come to see me as I am; for, if I die young, others will be able to tell you very little about me, and if I ive long, I shall probably only wish to remain silent."

On January 1, 1869, a few weeks after leaving her husband Hans von Bülow to live with Richard Wagner, Cosima began a diary that she would continue until February 12, 1883, the day before Wagner died. Under the button you can find a collection of diary excerpts in a string of tweets. The symphony as the embodiment of everything in life versus the symphony as a cartoonish representation of what is supposed to be grand, sanguine and awe-inspiring. The contrast between those two different kind of ways a piece of music can be percieved was palpable, almost beyond the point of salvation, when I listened to Bruckner's Sixth Symphony in performances by Joseph Keilberth and Sergiu Celibidache. It had been a while since a listening experience provoked such a strong reaction. I decided to not mince any words and write down what was on my mind. Over the years while listening to Wagner, a rule of thumb of sorts occurred to me that also can be applied to Bruckner. Don't play it too slowly because the music becomes, all too quick, a dragging procession in which the pathos rings hollow. For performers and interpreters it’s pivotal do not narrow the potential of a score to the flat flavours of one's own mind. Essential is to let the music speak for itself, as far as necessary and possible. (So much for the contemplations of an engaged listener.) This morning, over a cup of coffee and the morning paper, I listened to two versions of Anton Bruckner's Sixth Symphony, one of my favourite symphonies by the Austrian composer and organist. The first one conducted by Joseph Keilberth. A renowned opera conductor who was a familiar face in Bayreuth in the 1950s. His 1955 Bayreuther Ring cycle is regarded as benchmark and he is considered, not in the least because of that 1955-Ring, the first stereo recording of that work, as a Wagnerian of repute. It is not surprising that Bruckner also suited him well. His Bruckner recordings are a lot fewer in number, but the quality is no less. Die Sechste ist die Keckste Right from the start of the first movement, it becomes clear why Keilberth's performance with the Berliner Philharmoniker was for years the benchmark recording of Bruckner's Sixth. Under Keilberth's baton, Bruckner really comes to life. Under Keilberth, Bruckner is majestic and grandiose but also virile (!), fresh-faced, full of color and funny. The metaphor often brought up in connection with Bruckner, in which his symphonies are portrayed as cathedrals of sound, is hopelessly inadequate with Keilberth and that is one of the greatest compliments I can think of for this recording. Keilberth understands that maximum eloquence is not the same as trying to make a maximum impression. The difference with Celibidache's recording with the Münchner Philharmoniker that I listened to afterwards could not be bigger. Where Keilberth brings Bruckner's score to life, Sergiu Celibidache reduces it to a petty distortion of ideas about a grand and compelling life not yet been tested by reality. Celibidache's reading brings together two opposites in the worst possible way: adolescent dreams of grandeur in an over-analyzed approach. With Celibidache it is as if the music is no longer trusted to stand on its own feet and is considered only to find its way on the tight leash of a conductor. (That is the big difference with, for example, Knappertsbusch who is no speed demon either but whose Bruckner I very much enjoy. Knap at least puts his trust in the music and the magic of the moment.) The devout images that Celi conjures up may not seem out-of-sync with the devout Bruckner, the lifelong virgin with his childlike clumsiness towards women, but it does the Austrian in his most frivolous symphony a serious disservice ("Die Sechste ist die Keckste", according to Bruckner himself). With a sparkling rendition, Keilberth provides Bruckner with the splendour he so often lacked in real life. Keilberth allows Bruckner to transcend his limitations as a human being through his art. Celibidache denies Bruckner this testimony of true greatness. He denies Bruckner the merites of his artistry with which the composer tried to pull himself out of the swamp of his own shortcomings. Anton's fate is in cruel hands of performers such as Celibidache, who here shows himself to be the greatest conceivable opposite to the man whom he was to succeed in 1954 as chief conductor of the Berliner Philharmoniker, Wilhelm Fürtwangler (perhaps the most exhilarating and demon-driven Bruckner conductor of all time - after Furtwangler's death, the vacant position of chief conductor of the Berliner went to Herbert van Karajan; it left Celibidache with a grudge against Karajan and about every other conductor other than himself but that's another story). The grandeur Celibidache seeks is ludicrous; his Bruckner is slow and boring. His Münchner Orchestra is well versed in this repertoire but Celi makes them sound like a carnival band on Ash Wednesday. Like an ensemble that has lost all energy and is lurching along in an exercise on autopilot. A big disappointment. What earns this man his title of Brucknerian not only remains well hidden here, the accolades can be stowed away in the cupboard with the deepest drawers, this performance also fails to explore the terrain where music should ultimately have the last word. Where Keilberth grants Bruckner a place in the fullness of life with an execution that is complety self-evident, Celibidache directs him to a piece of wasteland where in vain he suspects the foundations of a cathedral. To deny Bruckner life by endowing him with a mind-numbing performance of his most uplifting symphony goes beyond the defect of a performance in which perfunctory premises lead to unsatisfactory ends. It is more severe. It can be, to remain in the spirit of the God-abiding Austrian composer, considered a sin. - Wouter de Moor

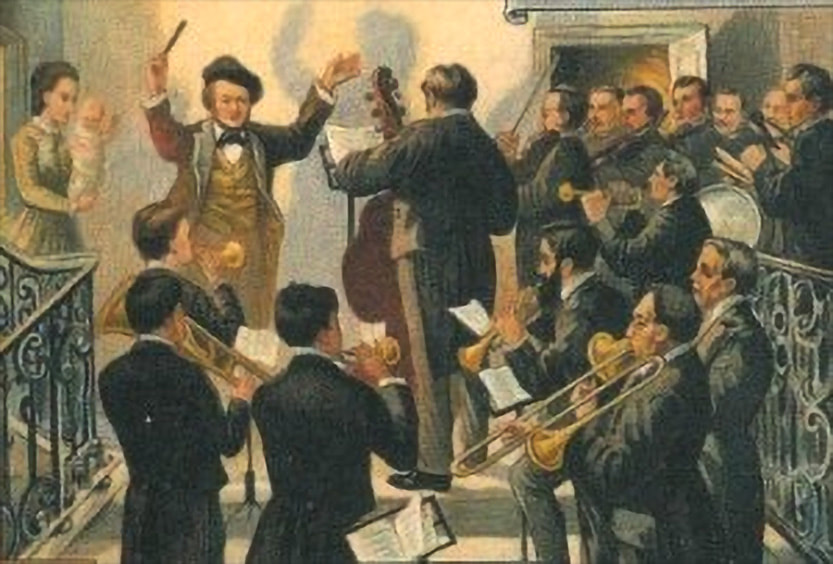

Cosima's diary - Sunday, 25 December 1870 About this day, my children, I can tell you nothing-nothing about my feelings, nothing about my mood, nothing, nothing. I shall just tell you, drily and plainly, what happened. When I woke up I heard a sound, it grew ever louder, I could no longer imagine myself in a dream, music was sounding, and what music! After it had died away, R. came in to me with the five children and put into my hands the score of his Symphonic Birthday Greeting. I was in tears, but so, too, was the whole household; R. had set up his orchestra on the stairs and thus consecrated our Tribschen forever! The Tribschen Idyll—thus the work is called. — At midday Dr. Sulzer arrived, surely the most important of R.'s friends! After breakfast the orchestra again assembled, and now once again the Idyll was heard in the lower apartment, moving us all profoundly (Countess B. was also there, on my invitation); after it the Lohengrin wedding procession, Beethoven's Septet, and, to end with, once more the work of which I shall never hear enough! — Now at last I understood all R.'s working in secret, also dear Richter's trumpet (he blazed out the Siegfried theme splendidly and had learned the trumpet especially to do it), which had won him many admonishments from me. "Now let me die," I exclaimed to R. "It would be easier to die for me than to live for me," he replied. In the evening R. reads his Meistersinger to Dr. Sulzer, who did not know it; and I take as much delight in it as if it were something completely new. This makes R. say, "I wanted to read Sulzer Die Meistersinger, and it turned into a dialogue between us two." The Siegfried Idyll is a symphonic poem for chamber orchestra, composed by Richard Wagner as a birthday present to Cosima, after the birth of their son Siegfried in 1869. It was first performed on Christmas morning, 25 December 1870, by a small ensemble on the stairs of their villa at Tribschen. Wagner's opera Siegfried, which was premiered in 1876, incorporates music from the Idyll. It was once thought that the Idyll borrowed musical ideas intended for the opera, but it is now known that the opposite is the case: Wagner adapted melodic material from an unfinished chamber piece in the Idyll and later incorporated it into the love scene (Ewig war ich) between Siegfried and Brünnhilde in the opera. This is a transcription of the interview Herbert Pendergast had in 1963, for Stereo Review, with Herbert von Karajan. In the interview Karajan talks about Bach, Boulez and Stravinsky as well the joy of listening to Louis Armstrong. CONVERSATION WITH VON KARAJAN

By HERBERT PENDERGAST THE FOLLOWING conversation with Herbert von Karajan occurred in Berlin this spring. It took place during various intermissions in Mr. von Karajan's rehearsals with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. The program he was preparing consisted of Bach's Magnificat in D and Stravinsky's Le Sacre du Printemps. There is an undeniable absence of common sense when one searches among recordings of a favorite piece of music with the assumption that there exists one version that can stand alone in saying all there is to say about such a piece. The idea that there is a performance of a piece of music, with all the information it contains, that makes all others superfluous is not only unlikely but also undesirable. It suggests that a composition is a puzzle that, as if it were exact science, knows only a single, fixed answer. As something that can be left alone after it is solved. Being in constant combat with the space on your CD-shelves - after purchasing another version of Tannhäuser or a Beethoven symphony - is not an end in itself, but it is a willing effort whose rewards (complementary or changing insight and arousing curiosity for a next rendition) are almost impossible to resist. A man needs, after all, a̶n̶ ̶a̶d̶d̶i̶c̶t̶i̶o̶n̶ a hobby. (Wagner is to blame here, he turned me into a collector by surprising me how different the performances of his operas can sound, he made me hungry for different versions, hence the many Ring-cycles that inhabit my m̶é̶d̶i̶a̶t̶h̶è̶q̶u̶e̶ living room now.) To restrict oneself to one version per composition. I manage with Vivaldi's Four Seasons but not with Wagner, as mentioned, and not with Mahler (and not with many others, the list of composers is, in fact, growing). In my aural travels through Mahler's second symphony, the quest for resurrection, I found myself, perhaps suprisingly, attached to Hans Vonk's rendition with the Residentie Orchestra The Hague from 1986. Surprisingly because its sonics are a bit muffled and its reading is somewhat restrained. This is Mahler played like he is Beethoven. More than relying on Romantic gestures this is a Mahler who prefers a more "classical" approach. Like Mahler doesn't dare to follow his own Romantic footsteps. Like he is afraid of the implications of his own musical intentions and innovations. This is a reading of Mahler, relaxed yet swift (the whole symphony fits on one CD), that displays everything in a natural, organic way and doesn't care (too much) about making a sonic impression. Here Mahler seems to understand that true heaviness is the result of the cumulation of all ideas, and not of the emphasizing of just a few. Pretty much he lets the music take care of itself and by doing so he seems almost shy in comparison to some of the big names in the catalogue (I think of Bernstein whose readings of Mahler's Second - both his first and second offering in his two Mahler cycles - are terribly overblown). It's, for all its imperfections, the instrumental execution is far from razor-sharp, a performance that's lyrical, remarkable capable of putting the extremes in Mahler's score in the right perspective (its "Urlicht" by Mahler-champion Jard van Nes comes out most seductive and the climax at the end sounds as the natural consequence of everything that preceeds it). Seemlingly effortless in achieving its musical aims, and, perhaps of its relatively restrained approach that invites more than it imposes, this performance never fails to move me and is, like a resurrection that lives up to its name, something that keeps coming back to me. Like a deep-rooted wish to defeat the temporality of life. A wish that, despite or thanks to the knowledge that one is immortal for only a limited time, seems persistent. Mahler, Hans Vonk, Residentie Orchestra The Hague, Maria Orán (soprano), Jard Van Nes (mezzo soprano), The Dutch Theater Choir – Symphony no 2 in C flat "Resurrection"

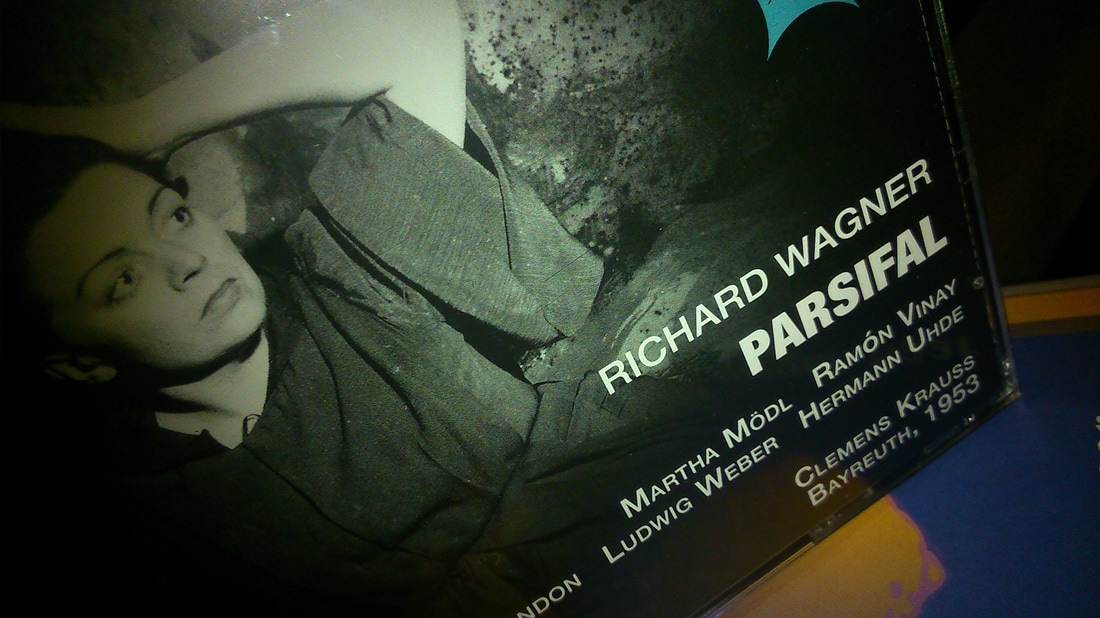

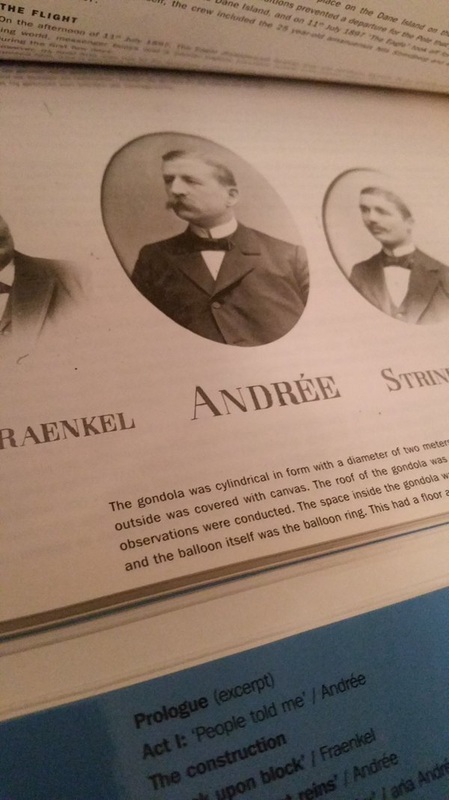

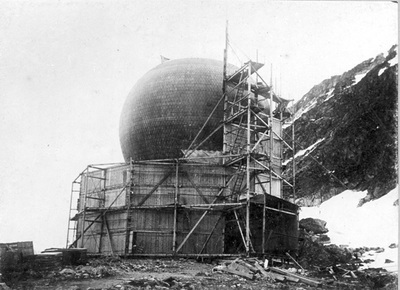

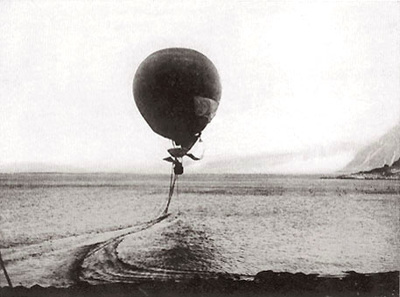

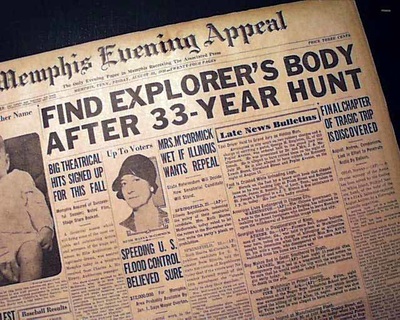

Parsifal (Bayreuth ‘53) with Clemens Krauss at the helm. In the same year that this wonderful Parsifal was performed Krauss gave us an equally wonderful Ring des Nibelungen. A performance that became my favorite live Ring. Listening to Krauss in Wagner makes me wonder if there ever was a better conductor for this music. Parsifal was the only Wagner opera that was composed exclusively with the acoustics of the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth in mind. It was the first opera that was performed in Bayreuth after the second World War. From its premiere in 1882 to the first cycle of performances in Bayreuth after World War II (in 1951) the opera was considered a "life-changing" event for those who were lucky enough to see it (among them Gustav Mahler, who attended the opera in 1883). This "life-altering" experience took me quite some time to digest. The opera comes pretty close to an oratory and can be an exercise in slowing down (I do appreciate Knappertsbusch '51 now but Goodall got me lost between the notes). It was not until I heard the Boulez Parsifal from 1970 that the music started to make sense to me. Thanks to the relatively fast tempi from Pierre Boulez - that were on par with Clemens Krauss' and Richard Strauss' renditions of Parsifal in Bayreuth. Boulez himself noted that his tempi were not that much faster than the tempi Hermann Levi conducted during the premiere in 1882 (in 1966 Boulez used 61 minutes for the second act vs. Levi 62 minutes, 70 minutes vs. 75 for Levi in the 3rd act and 100 minutes vs. 107 in the first act). Parsifal is often considered a solemn mass for true believers with its broad tempi to emphasize the spiritual grandeur of the whole thing. But it was the Parsifal from Clemens Krauss that converted me. Lively and swinging are not the words that are used to characterize the piece Parsifal is but Krauss does a wonderful job to make a case for it. I have the Andromeda remastering from 2009 and although the mono sound might not be for hifi-buffs the quality is more than acceptable for me. I noticed that after my visit to Bayreuth, having heard the famous acoustics first hand, I started to extrapolate the 50's Bayreuth sound into an impressive theater experience at home. If Richard Strauss’ Salome from 1905 marked the beginning of 20th century opera, Klas Torstensson’s The Expedition from 1999 would mark a worthy closing. It tells the story from Salomon Andrée’s ill-fated effort to reach the North Pole by balloon in 1897. The Expedition digs into musical means as diverse as dodecaphony, music concrete and a Puccini-kind of lyricism, and yet it makes one, organic whole in which musical boundaries do not seem to exist. Together with the use of electronics to generate the sounds of the rustle of the northern lights and crawling ice, this opera (the libretto is in Swedish) delivers a world of sound that is both hauntingly beautiful and harrowing creepy. I live with a borrowed copy of the CDs for a few years now (the rightful owner doesn't miss them that much and the CD of The Expedition seems to be out of print now – only a MP3-version is available on Amazon) and would welcome a re-issue of this masterpiece on CD that includes the beautiful and very informative booklet. It premiered at the Holland Festival in 1999 and was only performed four times since (in concert performances). With all the excitement that surrounded the premiere of the, thematical related, opera South Pole by Miroslav Srnka in mind (trailer South Pole - I hope to see it somewhere in the future) I would like to make a case for a stage production of Torstensson’s Expedition. Because it is too good to neglect and it sounds like the future of opera. It will of course not be without challenge to make a staging that is dramatically convincing but it would be well worth to witness the effort. It sounds like the future of opera For describing the music that accompanies the building of the balloon (noises of labour, not unlike Siegfried’s forging of the sword), the flight of the balloon and its crashing on the ice I delve into my vocabulary and come up with something like “industrial sound”, “atonal finesse” (the composer knows his Anton Webern) and “coloured noises”. It is counterparted by the arias of the fiancée of expedition member Nils Strindberg (sung by Torstensson’s wife Charlotte Riedijk) who is assigned with a few beautiful Puccini-like arias in which she’s lamenting her fate (of being left behind) and the fate of her spouse. The musical contrast between the icy world of the men and her own couldn’t be bigger but they don’t fall apart. They speak to each other in different languages but they stay connected. Her final aria after the men disappeared on the ice is heartbreaking beautiful. Torstensson composes without being dogmatic about the style or musical niche he is supposed to write in. This music is an experience on its own and reminds me of Gustav Mahler's attempts to catch nature into music. Certainly Torstensson’s music is different from Mahler's but it shares with him a combination of intuition, primal energy and musical complexity that forms an impossible-to-resist invitation to pay this unique world of sound a visit.

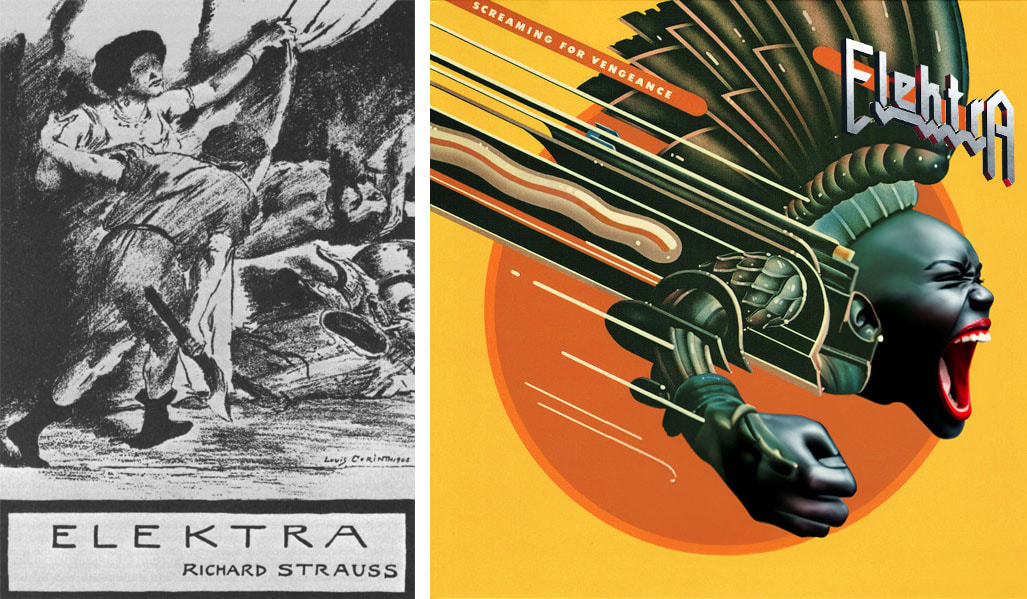

If Richard Wagner prepared music drama to enter the 20th century, Richard Strauss kicked in the door to the 20th century door with his shock opera Salome (in 1905). Salome brought Strauss fame (and a villa in Garmisch-Partenkirchen); in that opera he drilled into the deepest layers of human degeneration with unprecedented musical intensity. In the follow-up to Salome, Strauss went even a few steps further. With its weals and woes in the house of Atreus, Elektra took domestic relations to new dystopian lows and drama in the genre of opera to new (musical) heights.

I'm not expecially fond of so called cross-over. I don't look for a Walkürenritt played on an electric guitar, it takes away some of its substance and I don't prefer a Metallica song played with violins, it takes away an important part of its heaviness. Elektra is heavy, both in substance and sound and a stainless-steel memo that good music transgresses genres (makes them obsolete). If any opera deserves the term Heavy Metal Opera, it is Elektra, a screaming-for-vengeance music drama that gives many metal acts a run for their money.  Tannhäuser is Wagner's fifth opera. The story goes that famous tenor Jon Vickers - who sang many Wagner roles - refused to play this one because he found the character Tannhäuser despicable (it was due to his Christian believes that he thought so). Tannhäuser is seduced by Venus and lives in the mountain, that bears her name, a life of sin. In an attempt to bring opera to the people as a home theatre experience producer John Culshaw seasoned the Wagner recordings he made for Decca with all kinds of sounds that made the recordings in question by times sound like a radio play. In this Tannhäuser with Georg Solti at the helm that is no different. Solti’s conducting of Wagner troubles me. His status as a Wagner conductor is undisputed but it just doesn’t seem to work for me. With Decca he worked himself through the Wagner catalogue but the results never reach the echelon of benchmark recordings. To put it short: his conducting falls short in story telling. Solti is a man of large gestures and of the bombast Wagner so often is associated with. And perhaps that’s why I don’t like him. I don’t listen to Wagner because of the supposed loudness and sonic mayhem (I put on a Napalm Death record if I want that) but for the musical subtlety and the sheer quality of the notes that both are unequalled in the world of music drama. As a conductor Solti fails to show the listener the layers in Wagner’s musical world. It fails to transcends that world into a world of the mind in which no boundaries exist and in which the listener is more than happy to get lost. Instead it reduces a place of three dimensions into flatland. It’s Wagner for the fitness room but I put on some midtempo metal if I am looking for a soundtrack for the gym thank you. As a recording this Tannhäuser is like a movie that got his head stuck in the special effects department without having a clue about the lyricism that makes a story tick. And that’s all a big pity because, as always for Decca, the singers for Solti are top notch (although Rene Kollo might be an acquired taste for many). Especially Christa Ludwig as Venus is superb. She knows how to seduce a man but like Tannhäuser himself, who doesn’t want to be in the mountain of Venus any longer, this listener takes a run from it. |

Archives

September 2023

Name/dropping

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed